Abstract

A series of calcium borosilicate glasses with varying [B2O3], [MoO3], and [CaO] were prepared and subjected to 92 MeV Xe ions used to simulate the damage from long-term α-decay in nuclear waste glasses. Modifications to the solubility of molybdenum, the microstructure of separated phases, and the Si–O–B network topology were investigated following five irradiation experiments that achieved doses between 5 × 1012 and 1.8 × 1014 Xe ions/cm2 in order to test the hypotheses of whether irradiation would induce, propagate, or anneal phase separation. Using electron microscopy, EDS analysis, Raman spectroscopy, and XRD, irradiation was observed to increase the integration of MoO42− by increasing the structural disorder within and between heterogeneous amorphous phases. This occurred through Si/B-O-Si/B bond breakage and reformation of boroxyl and 3/4-membered SiO4 rings. De-mixing of the Si–O–B network concurrently enabled cross directional Ca and Mo diffusion along defect created pathways, which were prevalent along the interface between phases. The initiation and extent of these changes was dependent primarily on the [SiO2]/[B2O3] ratio, with [MoO3] having a secondary effect on influencing the defect population with increasing dose. Microstructurally, these changes to bonding caused a reduction in heterogeneities between amorphous phases by reducing the size and increasing the spatial distribution of immiscible droplets. This general increase in structural disorder prevented crystallization in most cases, but where precipitation was initiated by radiation, it was re-amorphized with increasing dose. These outcomes suggest that internal radiation can alter phase separation tie lines, and can therefore be used as a tool to design certain structural environments for long-term encapsulation of radioisotopes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The critical concern with nuclear power remains the growing need to deal with significant amounts of high-level radioactive waste (HLW) [1]. Owing to their ability to incorporate a wide variety of radioisotopes, as well as showing radiation resistance and chemical durability in aqueous environments, immobilization of radioisotopes from HLW in a borosilicate or phosphate-based glass is the current worldwide practice [2,3,4,5]. In these amorphous structures, waste loading is limited to ~ 18.5–25 wt% [2, 6] in order to prevent the precipitation of insoluble species such as molybdenum, platinoids, or rare earths (REs) that can result in unexpected phase separation [7] and thus lead to degradation of the wasteform during long-term storage [5, 8]. High concentrations of molybdenum are expected from postoperative cleanout, increased fuel utilization, weapons-grade waste, or Generation IV reactors [7, 9]. It is also a concern if increased waste loading is to be considered, as a means to minimize the final volume of waste for storage.

Molybdenum is a particularly problematic fission product limiting waste loading as it can cause crystallization of water-soluble alkali molybdate complexes (Na2MoO4, Cs2MoO4), known as yellow phase [7, 10]. This phase can act as a carrier for radioactive cesium, strontium, and minor actinides [11, 12], thus affecting the safety case for storage in a geological repository. In order to prevent yellow phase precipitation, increased incorporation of molybdenum into an alternative glass composition or selective and controlled formation of water-durable CaMoO4 [13] is currently of industrial interest [9, 14,15,16].

Within a glassy framework, molybdenum can exist in several oxidation states (Mo6+, Mo5+, Mo4+, Mo3+). However, in oxidizing or neutral conditions they are primarily hexavalent and take the form of MoO42− tetrahedra [17,18,19,20]. These tetrahedra are located in non-bridging oxygen (NBO) channels and remain unconnected to both the glassy framework and to each other according to Greaves’ structural model [21]. In this configuration, Ca2+ cations are octahedrally coordinated and bound to MoO42− entities in a scheelite-type configuration by weak long-range ionic forces [22,23,24]. This tetrahedral form of molybdenum is found in both crystallized molybdates and diluted molybdenum anions within a glassy phase [17, 25], hence why molybdenum has a limited solubility in glasses.

The formation of MoO42− alkaline or alkaline earth complexes can be induced by composition [22, 26, 27], controlled cooling during synthesis [28], external heat treatments [14, 29], or through redox chemistry [30, 31]. These tools can also be used to increase the solubility of molybdenum. A rapid quench rate of 104 °C min−1 has been found to increase incorporation up to 2.5 mol% MoO3 [28], while the inclusion of rare earths such as Nd2O3 has had a similar effect by increasing the disorder in the depolymerized region of the glass [16, 27]. Compositionally, the preferential charge balancing of BO4− and MoO42− anionic entities by available cations is an important factor in initiating liquid–liquid phase separation and determining molybdate speciation. These processes are a result of shifts in the coordination of boron, the network-modifying properties of cations, and the formation of NBOs, which can change the ring structures in the borosilicate glass framework [17, 26, 27, 32]. It is this relationship that will be further examined in this paper.

While chemistry is one factor affecting the incorporation of molybdenum in a waste glass composition, accumulated radiation damage created from the encapsulation of radioisotopes is another. Internal radiation constitutes α-decay of minor actinides, β-decay of fission products, and transitional γ-decay, which is a by-product of the other two types of decay. Collectively, these decay processes can cause atomic displacements, ionization, and electronic excitations, which can result in changes to long-range ordering, composition and phase separation tendencies. In glasses, phase transformations such as devitrification, precipitation, bubble formation, amorphous–amorphous phase segregation, or the clustering of cations are known to occur [2, 3, 10, 33], which can subsequently alter mechanical properties of the glass [34, 35].

From these three types of internal irradiation, the α-decay process causes the greatest disruption to structural order and is therefore responsible for most of the listed modifications [2, 3]. The heavy recoil nuclei created when α-particles (He2+) are ejected from a parent isotope interact predominantly through ballistic collisions resulting in a chain reaction of atomic displacements, while the high-energy α-particle primarily interacts through electronic collisions that will initiate some thermal recovery processes [2, 36, 37]. This process of electronic stopping can be described by the thermal spike model, in which a collision cascade is translated into a small cylinder of energy characterized by a temperature of 103 K [38]. In this model, thermal spikes associated with a high electronic energy loss are responsible for damage creation, while those with a lower energy loss can initiate some damage recovery [35, 39].

Theoretically, these thermal spikes could lead to localized relaxation or defect annealing. They could also provide the necessary energy required to overcome the activation barrier for precipitation. Therefore, the components of α-decay can propagate or remediate phase separation. Experimentally, single-phase borosilicate glasses subjected to external irradiation used to replicate the damage created by accumulated α-decay remained amorphous. However, changes to the connectivity of the borosilicate network, stored energy, density, and hardness were detected with a dependence on composition and dose [40,41,42]. Modifications to these properties were interestingly observed to reach a saturation plateau for a cumulative dose of 4 × 1018 α/g, at which point it is assumed that the processes of defect formation and self-healing reach an equilibrium [3, 41]. This saturation in modifications has been similarly observed in MD simulations [43], which indicates that this equilibrium state can be correlated with bonding metrics at the molecular level. Given current waste loading standards, this saturation in structural modifications is expected following ~ 1000 years of storage [2, 3]. By replicating the damage occurring in this timeframe, insight can be gained into the possible long-term structures of candidate wasteforms.

While extensive research exists on homogeneous glasses, there is a lack of understanding when it comes to phase-separated wasteforms that result from a high concentration of relatively insoluble species, such as molybdenum. This study primarily sought to comprehend the processes of phase separation in heterogeneous glasses containing molybdenum following irradiation. It aimed at identifying the mechanisms of radiation-induced phase transformations, and determining whether these alterations would (1) increase phase separation in the borosilicate network; (2) induce the precipitation of CaMoO4; or (3) remediate phase separation by increasing Si–O–B mixing, Mo retention or causing the amorphization of CaMoO4 precipitates.

Materials and methods

Compositions and sample preparation

Several non-active glasses and glass ceramics (GCs) were synthesized to test the immiscibility properties of the CaO–B2O3–SiO2 system when MoO3 was introduced into the glass, and the materials were subsequently subjected to Xe-irradiation, as a means to test the radiation response to α-decay. Two series of glasses that systematically varied [B2O3] and [MoO3] were created, the compositions for which can be found in Table 1.

The CB series contains glasses with increasing [B2O3] for a fixed [SiO2]/[CaO] ratio, MoO3 content, and amount of Gd. In this case, the rare-earth dopant can be considered as an actinide surrogate and can therefore be used as an indicator for potential incorporation sites of radioactive elements. The second, the CM series, includes compositions with increasing [MoO3] within a calcium borosilicate glass normalized to inactive French nuclear waste glass SON68. It was used to probe how the molybdenum incorporation was affected by irradiation when BO4− and MoO42− groups must compete for limited charge compensators.

Glass batches of ~ 30 g were prepared by mixing and then melting powders of SiO2, H3BO3, CaCO3, MoO3, and Gd2O3 in a platinum–rhodium (90/10) crucible at 1500 °C for 3 h, before crushing and re-melting glasses for 2 h. A double melt was used to try and increase homogeneity, but all compositions remained multi-phased despite various techniques to increase the quench rate or attempt mixing at high temperature. The calcium borosilicates were too viscous to be poured, so they were quenched using a water bath and tapped out of the crucible with a hammer, after which all glass fragments were annealed for 24 h at 520 °C to reduce internal stresses. From these fragments, specimens were roughly cut to ~ 4 mm × 4 mm in surface dimensions and then were hand polished successively using incremental SiC grit paper, followed by 3 μm and 1 μm diamond polishing to achieve a uniform thickness of ~ 500 μm.

Irradiation experiments

Swift heavy ion (SHI) irradiation can be used to replicate the damage resulting from the nuclear and electronic components of α-decay on an accelerated timescale with some accuracy [2, 44, 45]. In this experiment, 92 MeV Xe23+ ions, with an average flux of 2.3 × 109 ions/cm2 s, were used to irradiate five different sample sets with fluences of 5 × 1012, 1 × 1013, 4 × 1013, 8 × 1013, and 1.8 × 1014 ions/cm2 on the IRRSUD beamline at Ganil. According to TRIM calculations [46], this resulted in an estimated penetration depth of ~ 13 μm.

Multiple fluences were acquired to provide information on the mechanisms of structural transformations, as well as testing whether a saturation in modifications could be detected for a timeframe consistent with ~ 1000 years of storage. In homogeneous sodium borosilicate glasses, this saturation occurs at a fluence of 1 × 1014 ions/cm2 [3, 41].

Characterization techniques

As this project investigated the effects of radiation damage in complex structures, several analytical techniques were required to characterize changes in the various amorphous phases. Morphology, composition, bonding order, and phase transformations were analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Raman spectroscopy, Magic-Angle Spinning Nuclear Magnetic Resonance spectroscopy (MAS NMR), and X-ray diffraction (XRD). These techniques could provide insight into amorphous–amorphous phase transformations, versus precipitation of crystalline phases following irradiation. In this context, a phase transformation refers to changes in material properties resulting from alterations in the connectivity of amorphous network formers for a fixed composition, though the phase itself will remain amorphous.

SEM backscattered (BSE) imaging and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) were performed at low vacuum (0.06–0.08 mbar) on a Quanta-650F with a 5–7.5 keV beam resulting in a penetration depth of ~ 1 μm. For EDS analysis, measurements were collected with a 8-mm cone in order to reduce skirting effects, thus providing information on the interface between phases, and the relative composition of each identifiable phase. Images were collected using FEI Maps software, while acquisition and analysis for EDS was performed using Bruker ESPRIT software.

Raman spectra were collected on a Horiba Jobin–Yvon LabRam300 spectrometer with a 300-μm confocal hole and a holographic grating of 1800 grooves per mm, coupled to a Peltier cooled front illuminated CCD detector (1024 × 256 pixels in size), which resulted in a spectral resolution of ~ 1.4 cm−1 per pixel over the 150–1600 cm−1 spectral range. The excitation line at 532 nm was produced by a diode-pumped solid-state laser (Laser Quantum) with an incident power of 100 mW focused on the sample with an Olympus 50x objective. Multiple acquisitions (3–10) were made for each phase from a similar location within each phase to provide some reliability of detected features.

11B MAS NMR (\( \mu_{z} = 2.6887;\; \gamma = 8.5847 \times 10^{7} \;{\text{rad/T}}\,{\text{s}} \)) was only performed on samples prior to irradiation, as the irradiation volume was small (1:42 of the total sample volume) and analysis would require monoliths to be powdered, thus limiting further investigation. Experiments were conducted on a Varian Infinity Plus spectrometer with an 11.74 T superconducting magnet, using 2.5-mm probes, and zirconia rotors. At this magnetic field, the probe was tuned to the Larmor frequency of ~ 160.37 MHz. Approximately 9–13 mg of packed powdered solids was used for each measurement, with spinning speeds of 20 kHz. 90° pulses with a 0.7 s pulse delay, and 5 μs receiver and acquisition delays were used. Chemical shifts were then measured relative to a secondary solid standard of NaBH4 (− 42 ppm), with the primary liquid standard being BF3Et2O (0 ppm).

XRD was performed on a Bruker D8 ADVANCE equipped with Göbel mirrors for a parallel primary beam and a Vautec position sensitive detector with a 0.6-mm slit using CuKα1 (λ = 0.15406 nm) and CuKα2 (λ = 0.15444 nm) wavelengths. Spectra were collected for a 2θ = 10°–90° range with a 0.02° step size and a 10 s per step dwell (~ 11 h acquisition). This configuration resulted in a penetration depth of ~ 6 μm around 20° (2θ) and of ~ 54 μm around 90° (2θ). XRD was primarily used to identify potential crystallization or else confirm the amorphous nature of all heterogeneous phases. Pristine glasses were examined as both powders and monoliths.

Results

Structure of samples prior to irradiation

The calcium borosilicates synthesized in this study showed a unique heterogeneous structure of embedded immiscibility (see Fig. 1). Microscopy revealed three phases within this structure that were confirmed to be amorphous by XRD. The residual matrix was Si-rich and referred to as phase A, while several large randomly distributed droplets rich in Ca (and Mo) of varying size are referred to as phase B. See schematic in Fig. 2 for visualization of phase assignments. Within these phase B regions, there were additional phase C droplets (5–50 μm in diameter) that were compositionally a mixture of phases A and B with a tendency toward phase A.

Schematic of immiscibility within calcium borosilicate glasses [47]. The residual phase A is rich in Si, while heterogeneously distributed deposits of varying size called phase B are rich in Ca (and Mo). Within these phase B regions, there are additional deposits with varying geometry that are designated as phase C and are compositionally a mixture of phases A and B

While phase B deposits were generally spherical or elliptical, phase C droplets were found in various geometries, as Fig. 3 illustrates and labels accordingly. In addition to varying droplet geometry, a non-uniform distribution of phases B and C were found for varying domain sizes. Medium (75–150 μm) to large (> 150 μm) deposits of phase B had interspersed immiscible phase C droplets (3–50 μm), while smaller phase B deposits were free of phase C. Furthermore, the location of phase C droplets within larger phase B deposits was dependent on composition.

In the CB series, increasing [B2O3] caused greater areas of immiscibility to be formed in terms of the size of phase B, and the number of phase C droplets within phase B (see Fig. 1d–f), which were also observed to become more spherical. This result indicates that the separated phase B acts as a carrier for boron. As the size of phase-separated regions increased, the general order of MoO42− tetrahedra in the amorphous phase also increased and approached a similar structure to that found for crystalline CaMoO4 according to Raman spectroscopy (see ESI). Increasing [MoO3] in the CM series similarly caused areas of immiscibility to grow, and the morphology of phase B deposits to become more spherical from originally ellipsoidal geometries (see Fig. 1a–c). This occurred alongside the formation of smaller phase C droplets closer to the A–B interface, with the size of phase C droplets in the center of phase B becoming more uniform. Microstructural changes following synthesis have been explored in more depth elsewhere [47], but a summary of conclusions is provided above to understand changes following irradiation.

It is evident that the complex microstructures observed in Fig. 1 are representational of phase separation within the borosilicate network. This can be tied to the coordination of boron, which is known to affect the competition of Ca2+ available for charge balancing MoO42− and BO4− units [22, 26], as well as the degree of Si–O–B mixing within the borosilicate framework [15, 48, 49]. The 11B MAS NMR spectra in Fig. 4 illustrate the concentration effects on boron coordination. As [B2O3] increased, the proportion of BO4− groups centered around − 1 ppm [50, 51] remained fairly constant. In contrast, the quadrupolar BO3 peak centered around 10 ppm that is composed of two complex contributions from BO3 in ‘ring’ (primarily boroxyl rings) and ‘non-ring’ (BO3 units diluted in the glass network) structures [26, 50, 52] experienced a shift toward the formation of ‘ring’ structures as [B2O3] increased. In contrast, there was a noticeable decrease in [BO4−] as MoO3 was included in increasing proportions in the CM series. A minor shift in the distribution of the BO3 group from ‘non-ring’ to ‘ring’ was also observed as [MoO3] increased. It is important to identify that increases in [B2O3] and [MoO3] are concurrent to a decrease in [CaO], which may therefore be correlated with the structure of BO3 groups.

Effects of radiation damage

In order to make morphological comparisons in these heterogeneous structures, analysis focused on the size and distribution of phase C droplets within similarly sized phase B regions, and along the A–B interface between phases. This was used to gauge the level of mixing between phases and to identify possible mechanisms of alteration. Several transformations were observed following irradiation, which are illustrated and labeled in Fig. 5.

Compositions with changing [B2O3]

Following Xe-irradiation, calcium borosilicate glasses were still found to be composed of three phases (A, B and C) with embedded immiscibility. Samples in the CB series all exhibited changes to the size and distribution of phase C droplets, as well as minor distortions to the A–B interface with increasing fluence. In samples with [B2O3] ≤ 15 mol%, extended edge spattering of phase C deposits occurred, which lead to particle segregation and the formation of smaller droplets (< 12 μm) for irradiation doses ≥ 8 × 1013 ions/cm2 (see Fig. 6). While smaller phase C droplets were generally observed following irradiation, droplet geometry varied based on the location within phase B. Larger (13–17 μm) phase C droplets located near the A–B interface were spattered, while those in the center of phase B coalesced to a more spherical geometry, indicative of a non-homogenous mechanism of alteration within phase B. Furthermore, the location of phase C droplets approached the A–B interface with increasing irradiation dose as Fig. 6 indicates. Combined, these changes indicate a more uniform distribution in the location of phase C, along with the formation of more similarly sized droplets, which suggests a diffusion based mechanism of alteration.

For CB23, phase C segregated into smaller particles in the center of phase B similar to that observed for CB7 and CB15, but droplets remained spherical in geometry until a fluence of 1.8 × 1014 ions/cm2, as Fig. 7 indicates. At this dose, larger phase C droplets (~ 15 μm) located near the A–B interface began to spatter, and a belt of very small (2–3 μm) droplets formed next to the interface (see Fig. 7d). This result suggests that radiation-induced changes to the microstructure of separated phases are delayed as [SiO2]/[B2O3] decreases.

Despite variations in the geometry and size of phase C droplets as a function of [B2O3], distortion to the A–B interface was observed for all samples in the CB series for fluences greater than 4 × 1013 ions/cm2. This can be correlated with the relative bond strength at the interface, or phase-specific properties that promote or prevent ion interactions and therefore damage and recovery processes toward a specific phase.

These morphological changes occurred alongside changes to the relative concentration of elemental oxides within the three phases. As Fig. 8 illustrates, several nonlinear trends for [Si], [Ca], [Mo], and [Gd] were observed for each of the phases with respect to dose. At low doses, irradiation caused migration of Ca, Mo, and Gd to phase C. It is hypothesized that this occurs through inter-diffusion between phases B and C, which is why an initial drop in [Si] was concurrently observed in phase C. The initial growth in [Mo], and to a larger extent [Ca], was simultaneously observed across all phases, which is consistent with the clustering of Mo and Ca ions from the bulk toward the surface, in addition to diffusion across phases. A critical point was observed at 4 × 1013 ions/cm2, at which dose possible dissolution of Ca and Mo back into the bulk may have occurred, along with compaction of the silica network. The influx of [Si] in most of the phases for this dose range could also be correlated with the relative amount of [B], which could not be accurately measured using EDS. For doses greater than 4 × 1013 ions/cm2, both Ca and Mo returned to the surface with a preference for phase B, and with increasing fluence, for phase C as well. In contrast, [Gd] peaked in all phases at 1 × 1013 ions/cm2, after which there was a uniform dissolution into the bulk with the magnitude of change the greatest in phase B. This result implies that Gd3+ ions were randomly located within the borosilicate network and primarily acted as a network modifier free to migrate between phases, or to the bulk following irradiation.

The results in Fig. 8 illustrate the complexities of cross phase elemental analysis following irradiation. Overall, results indicate that compositional changes following irradiation primarily occur through Ca diffusion between phases, combined with a significant mechanism of Ca and Mo bulk-to-surface diffusion. This latter effect may be a result of an electric field gradient created by the impinging Xe23+ ions, as has been observed to occur with alkali ions following β-irradiation [45, 53]. It was further observed that the relative concentration of each element either saturated for doses between 8 × 1013–1.8 × 1014 ions/cm2, or in the case of Si returned to values closer to pristine conditions. This result suggests some preservation of the units being charge compensated at high doses. An assumption was made here that the general trends observed at the surface were reflective of those deeper in the irradiation volume, although additional depth profiling would be required to confirm this assumption.

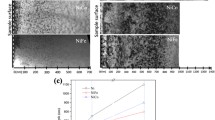

Raman spectra indicate that modifications to morphology and the normalized concentration of elements may be originating from local changes in the bonding of network formers. The spectra in Fig. 9a illustrate a shift of the R band (~ 450 cm−1) attributed to mixed Si–O–Si and Si–O–B bending and rocking [41, 50, 54, 55], as well as B–O–B rocking (~ 500 cm−1) [56] to higher wavenumbers following irradiation. This indicates a reduction in the intertetrahedral angles between network formers, which implies the formation of smaller or distorted ring structures. This shift occurred alongside growth of the D1 (~ 490 cm−1) and D2 (~ 600 cm−1) defect bands, which are assigned to four-membered and three-membered SiO4 rings, respectively [57].

Raman spectra of a Si-rich and b CaMo-rich phases in CB7 and CB23 following Xe-irradiation. The bottom spectrum of each regional collection represents a pristine sample after which irradiated samples with increasing fluence (5 × 1012, 1 × 1013, 4 × 1013, 8 × 1013, and 1.8 × 1014 ions/cm2) are illustrated in ascending order, therefore matching the designations presented in the legend. Radiation-induced shifts have been labeled on the plots

Concurrently, there was also growth of both the boroxyl ring band (~ 807 cm−1) assigned to the symmetric vibrations of 6-membered BO3-triangles [58, 59], and the low intensity broad band around ~ 1445 cm−1 associated with B–O− bond elongation in metaborate chains and rings [41], along with the minor emergence of broad bands assigned to rings containing one or two tetrahedrally coordinated boron units (~ 700–800 cm−1) [41, 55, 59] in high [B2O3]-bearing samples. The formation of defects in the silica rings structures, along with growth of borate-like characteristic bands, indicates that irradiation damage promotes phase separation within the borosilicate network by reducing the Si–O–B connectivity. These network changes are visible in the spectra of phase A in Fig. 9, which also shows that growth of the D1 and D2 defect bands is more prevalent for low [B2O3], while growth of borate-like bands is more significant for high [B2O3]. In low [B2O3] compositions, there was also broadening of a weak band at ~ 800 cm−1 attributed to O–Si–O symmetric bond stretching associated with the motion of Si atoms against its oxygen cage [50, 60], further indicating a dominance of silicate-type features in phase A of CB7, and the subsequent structural distortions of SiOx units following radiation damage.

While phase A contained bands associated with silicate and borate-type features, phase B primarily had Raman bands associated with the molybdenum environment. Several bands associated with vibrations for the internal MoO42− modes in a powellite-type structure could be identified within phase B. They are as follows: ν1(Ag) 878 cm−1, ν3(Bg) 848 cm−1, ν3(Eg) 795 cm−1, ν4(Eg) 405 cm−1, ν4(Bg) 393 cm−1, and ν2(Ag + Bg) 330 cm−1 [61]. These modes represent symmetric elongation of the molybdenum tetrahedron, asymmetrical translation of double degenerate modes, and symmetric and asymmetrical bending, respectively [62]. Many of these vibrations can be seen in the spectra for phase B (see Fig. 9b), but it is important to outline that no crystallization was detected in these compositions according to XRD or SEM microscopy utilizing electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD). It is predicted that while the molybdenum environment in these compositions has similar vibrations to crystalline CaMoO4, a sizeable number of defects prevents perfect stacking and orientation of anions and thereby diffraction.

Compositionally, increasing [B2O3] was observed to increase the degree of ordering and clustering of MoO42− groups within phases B and A. This is evident from the sharper MoO42− bands in CB23 relative to CB7 (see Fig. 9). Following irradiation, these vibrations were observed to broaden with increasing fluence for all compositions. This broadening occurred alongside growth of a band at ~ 910 cm−1, which is associated with the symmetric stretching vibrational modes of isolated MoO42− units dissolved in an amorphous network [27]. This dual modification was also observed in phase A of CB23, where a significant damping of these MoO42− bands also occurred. Collectively, these results suggest increased disorder within the molybdenum environment, resulting in the isolation and increased integration of MoO42− anions within the borosilicate network of phases A and B that subsequently prevented powellite crystallization in these heterogeneous amorphous phased systems according to XRD.

While this increased disorder in the molybdenum local environment was a general trend found for high Xe fluences, initial irradiation appeared to cause ordering and clustering of MoO42− groups, along with the disappearance of silicate-based features in small phase B deposits that did not contain phase C droplets. These types of deposits were common in compositions with low [B2O3], hence why this anomaly can be observed for CB7 irradiated with 5 × 1012 ions/cm2 in Fig. 9b. However, increasing the irradiation dose caused a broadening of these MoO42− bands, as was similarly observed for CB23 irradiated with any fluence. It suggests that compositions with low [B2O3] experienced a stage of thermal relaxation at low Xe fluences that enabled MoO42− ordering, followed by the creation structural defects with increasing dose.

Compositions with increasing MoO3

Changes to the morphology of phase C following irradiation were dependent on the initial size of phase B. In the glass composition without molybdenum (CM0), large phase B deposits (> 150 μm) developed phase C droplets closer to the A–B interface. For fluences ≥ 1 × 1013 ions/cm2, these phase C droplets grew to 25–40 μm in diameter, while those in the center of phase B were found in medium (~ 15 μm) and small (< 5 μm) sizes. For irradiation doses exceeding 1 × 1013 ions/cm2, an interesting dispersion of phase C spherical droplets located near the A–B interface occurred, as Fig. 10 indicates. The presence and modification of these large spherical droplets suggests an initial coalescence of phase C to form those droplets > 15 μm at low doses, followed by edge dispersion, which indicates an increased degree of inter-diffusion between phases B and C at higher doses. The location of these deposits in relation to the A–B interface also suggests some diffusion of phase C constituents toward phase A. In smaller phase B deposits, the formation of very small (< 5 μm) phase C droplets was also found to occur in a belt near the A–B interface, along with extended edge spattering or segregation of larger (13–26 μm) phase C droplets (see first two columns of Fig. 10). As the formation of a belt of small deposits near the A–B interface was also observed in CB23 (see Fig. 7), it suggests that smaller phase B deposits in CM0 are richer in B2O3, hence why similar modifications are observed.

When molybdenum was introduced into this system, a similar dispersion and segregation of phase C droplets was observed following irradiation, but to a larger extent than that seen for CM0. In these compositions (CM1 and CM2.5), it appeared that the size of phase C droplets on average decreased, while the number of droplets increased (see Fig. 11). In addition to a shift toward smaller values in the size range of phase C, a new category of very small deposits was also observed. Prior to irradiation, phase C droplets were found to range from 5 to 20 μm in equivalent diameter, but the following irradiation several deposits < 2 μm were also observed. Moreover, these phase C droplets also appeared to take on a more spherical shape from initially spattered geometries following segregation. In terms of location, phase C droplets also became more uniformly distributed within phase B following irradiation. Combined with the shift in the size of phase C, results suggest that changes in the structure of phase B enabled a reorganization of phase C particles to take place and that diffusion of elements from phase C was a significant mechanism of alteration.

Comparative analysis from samples in the CM series suggests that incorporation of MoO3 in a calcium borosilicate matrix decreased the heterogeneity within phase B following irradiation by accelerating the migration and segregation of phase C into smaller deposits. This shift in the size distribution of phase C also appeared to occur in the sample without molybdenum, but to a lesser extent with the level of segregation non-uniform across phase B. These collective results imply that inclusion of MoO3 produced defects within the boron-rich phase B following synthesis, which created diffusion pathways and therefore enabled greater microstructural changes following irradiation. This initial defect population can be correlated with a higher [BO3] relative to [BO4−] according to Fig. 4.

Quantitatively, the atomic concentration profile at the surface followed a similar trend to that observed in Fig. 8 with Ca and Mo cross phase diffusion and bulk-to-surface precipitation as the main mechanisms of alteration. Following irradiation with 1.8 × 1014 ions/cm2, the [Si]/[Ca] ratio in CM0 of phase B increased from 2.03 to 2.54, and it decreased in phase C from 9.30 to 6.00, as compared to pristine samples. This result supports a predicted mixing between the phases with Ca diffusion from phase B to phases C and A occurring, according to EDS analysis. In CM2.5, a similar increase in the [Si]/[Ca] ratio of phase B from 1.25 to 2.02 and a decrease in phase C from 9.04 to 4.39 (with a maximum estimated standard deviation of ± 0.02 for all ratios) took place following a fluence of 1.8 × 1014 ions/cm2. The differences in these ratios further support the hypothesis that MoO3 inclusion created more structural defects in the borosilicate network, thus enabling easier release and migration of cations. A general increase in the [Ca]/[Mo] ratio was also observed across all phases in CM2.5, which implies bulk-to-surface Ca diffusion, along with possible changes to the dissolution of Mo-groups.

These microstructural and compositional changes can be correlated with alterations in bonding within the various amorphous phases. Raman spectroscopy showed similar shifts in the R band to higher wavenumbers, along with growth of the D1 and D2 defects in all compositions following irradiation (see Fig. 12). In this series, increasing [MoO3] to 2.5 mol% appeared to limit the reformation of boroxyl rings, which suggests remediation of some B-rich and Si-rich phase separation with increasing fluence. In contrast, CM0 showed the progressive growth of both the D2 defect and the boroxyl ring band, along with growth of Q3 over Q2 where Qn represents the Si–O stretching mode for SiO4 tetrahedra with n bridging oxygen (850–1250 cm−1) [50, 60].

Raman spectra of Si-rich Phase A in CM0, CM1, and CM2.5 at pristine conditions, and following Xe-irradiation with 1 × 1013 ions/cm2 and 8 × 1013 ions/cm2. For each collection of three spectra, the bottom represents the pristine sample and the top the highest fluence in accordance with the ordering in the legend

In addition to changes in the borosilicate network, initial radiation was also observed to significantly dampen internal MoO42− vibrational modes, as well as induce growth of the band at ~ 910 cm−1 assigned to MoO42− dissolved in amorphous networks of CM2.5. This change in the molybdenum environment occurred in both phases A and B (see ESI for additional Raman spectra). While broadening of the MoO42− bands between ~ 770 and 970 cm−1, as well as those between ~ 300 and 400 cm−1 indicate an increasing degree of disorder in the molybdenum environment within phase B, the sustained presence of these bands suggests that molybdenum remains tetrahedrally coordinated to oxygen. More to the point, while some units may become isolated in the amorphous network, there were still significant volumes of clustered units that gave rise to the internal MoO42− modes, albeit much broader in shape.

Comparatively, sharper MoO42− bands in the CB series (see Fig. 9) suggest that a lower [SiO2]/[B2O3] promotes and sustains greater ordering within the molybdenum environment following irradiation. It also suggests that [B2O3] has a primary impact on controlling the modification of separated phases in terms of network ring structures, order in the molybdenum environment, and diffusion of phase C within phase B, while [MoO3] has a secondary effect.

In contrast to most of the other compositions in this series, damping of the band at ~ 910 cm−1 was observed in CM1 at low fluence (5 × 1012 ions/cm2), which indicates a relaxation stage that increased the ordering in the molybdenum environment. This claim is supported by XRD results that identified the formation of a single crystal in the [0 1 4] direction (see ESI for diffractogram). With increasing irradiation fluence, no crystallization could be detected by XRD, and stabilization in the Raman mode at ~ 910 cm−1 was observed.

Discussion

This paper sought to understand how the immiscibility properties of heterogeneous structures and the incorporation of molybdenum would be affected by irradiation damage. It primarily addressed whether irradiation could propagate or remediate existing phase separation, or induce precipitation of CaMoO4, and the physical processes in which these changes could occur.

Phase separation within pristine CaO–B2O3–SiO2

The ability for a glass to incorporate molybdenum is dependent on the initial amorphous structure, which can be defined by the short- and medium-range order of glass constituents. In an oxide glass, components are generally split into two categories. They are network-forming units within the oxygen sublattice and network-modifying units [21]. Elements with small ionic radii and high valencies such as Si, B, Al, or P generally form the glass network with covalent bonds to oxygen, while cations such as alkalis, alkaline earths, or rare earths are further divided into two main groups. The first is network modifiers, which break up the network and thus favor phase separation, and the second is charge compensating network formers, which counteract the effects of immiscibility. The coordination and connectivity of the network-forming oxide units will determine the role of cations and therefore other properties of the glass [52, 57, 63, 64].

The base glass for compositions in this study fell within the immiscibility dome of the CaO–B2O3–SiO2 system [65,66,67], thus resulting in an embedded microstructure with three amorphous phases in glasses with and without molybdenum. The formation of these immiscible microstructures is predicted to occur through a two-step process. Step one involves the Si-rich phase A and Ca (and B)-rich phase B forming two randomly distributed domains during melt cooling. During step two, phase B droplets coalesce as cooling continues. Concurrently, phase A immiscible droplets within these larger regions of phase B mix with the surrounding phase B to form a new phase C [47]. The size and shape of phase-separated domains were dependent on composition, with [B2O3] and [MoO3] both found to increase the size of phase B domains, induce a reduction in the coordination of boron, and initiate the formation of boroxyl rings, as well as increase the ordering within the molybdenum environment. These changes can be correlated with a predicted increase in the phase separation temperature (TPS) during synthesis [30, 47].

In the calcium borosilicate base glass, the origin of phase separation between network formers can be connected to the high field strength of Ca2+ ions, which has been noted to cause formation of NBOs [17, 52, 68, 69]. This implies that Ca2+ primarily acted as a network modifier and enabled the BO4− → BO3 + NBO conversion during synthesis. Furthermore, the insertion of MoO3 in the borosilicate network was observed to further increase formation of BO3 units as 11B MAS NMR results indicate, and thus decrease Si–O–B connectivity and promote the mobility of Ca ions [32, 70]. This is in contrast to soda lime borosilicate glasses, which were observed to have little effect on the [BO4−]/[BO3] ratio with the inclusion of MoO3 [26]. This indicates that in the absence of Na+ ions, the influence of increasing [MoO3] via modifications to the availability of Ca2+ ions for charge compensation becomes more significant in causing the BO4− → BO3 + NBO conversion. These results are, however, representative of the bulk glass and give no insight into the relative contributions from each phase.

Nevertheless, it can be hypothesized that the BO3 group shift from ‘non-ring’ to ‘ring’ as both [B2O3] and [MoO3] increased are representative of changes within the distinct phases, as is the case in Pyrex glass [51]. In this multi-domain system, BO3 in ‘non-ring’ to ‘ring’ structures do not mix, but instead form two separated networks, where BO4− groups are connected to BO3 ‘ring’ structures. Using this model, it can be rationalized that two of the phases have different [BO4−]/[BO3(‘ring’)] ratios, while the other is primarily BO3 in ‘non-ring’ formations.

Radiation effects on molybdenum incorporation

The presence of MoO42− Raman vibration modes, particularly in phase B of samples with [MoO3] = 2.5 mol%, would suggest CaMoO4 crystallization; however, this was not detected in most compositions using multiple diffraction techniques. These observations suggest that the formation of defects prevented the ordering of MoO42− chains and thus the formation of a scheelite-like crystal structure. However, it is predicted that crystallization is possible if enough defects are annealed from these Mo-rich zones. As previous works support [22, 32], it can consequently be assumed that MoO42− groups are found in a similar environment whether in the amorphous or crystalline phase, with the amorphous structure a precursor to crystallization.

In these heterogeneous amorphous calcium borosilicates, Xe-irradiation was observed to increase the integration of MoO42− anions according to Raman spectra that showed an increase in the area of the band attributed to dissolved molybdenum in the amorphous network. This is a result of an increase in the general structural disorder between and within amorphous phases, which occurred in some part through defect-assisted diffusion of Ca and Mo ions. Increased disorder subsequently prevented the precipitation of crystalline CaMoO4 in most systems according to XRD, which suggests a beneficial outcome of irradiation in preventing uncontrolled crystallization that can alter physicochemical properties of the glass during long-term storage. This result was similarly observed in samples that were β-irradiated [47], which indicates that in amorphous systems with molybdenum and without prior crystallization, the effects of any type of radiation will produce similar results in preventing crystallization through the creation of accumulated defects.

While XRD indicates that most of the heterogeneous calcium borosilicates (CM1, CM2.5, CB7, CB15, and CB23) remained amorphous following irradiation, there was one exception. CM1 irradiated with 5 × 1012 ions/cm2 showed the formation of a single crystal with [0 1 4] orientation. This finding indicates either radiation-induced precipitation, which can be considered a similar process to the increased ordering of MoO42− units observed by Raman spectroscopy in CB7 irradiated with 5 × 1012 ions/cm2 (see Fig. 9), or initial sampling variations in heterogeneous systems that allowed for some specimens to have crystallites. As bulk powder XRD measurements made prior to irradiation did not show any crystal peaks, the former explanation is more likely.

Radiation-induced precipitation of molybdate phases has not been previously observed, but CaMoO4 formation has been seen following heat treatments greater than or equal to ~ 630 °C [14, 29, 71]. Although the bulk is unlikely to reach this temperature from the deposited energy of Xe ions, localized areas along ion tracks could theoretically create the necessary environment needed for nucleation according to the thermal spike model [38]. It is further predicted that if not ionically bonded, MoO42− anions and Ca2+ cations are attracted by weak dispersion forces by virtue of being in close proximity to each other within the amorphous phase following synthesis. Subsequently, the kinetic energy created along ion tracks from a dose of 5 × 1012 ions/cm2 must have been able to initiate the precipitation of small and isolated crystals without steric hindrance. In contrast, more energy consistent with fluences ≤ 1 × 1013 ions/cm2 created significant disorder and therefore re-amorphized any formed precipitates, as no crystallization was detected by XRD at all other doses. This process of radiation-induced amorphization occurs through heterogeneous defect accumulation for a given defect density [72, 73] and varies from temperature-induced amorphization, which would result in a homogeneous random configuration of atoms. Within the system studied here, it is hypothesized that amorphization of single crystals, and the increased integration of MoO42− units occurs by increasing the general disorder within depolymerized regions of the glass where molybdate formation is expected [20, 21, 25, 27].

Although CM1 contained less molybdenum than CM2.5, it was the composition that showed formation of a crystallite following a dose of 5 × 1012 ions/cm2. This was predicted to result from the initial distribution of Mo anions following synthesis. In CM1, the viscosity of phases A and B is predicted to be more similar given that TPS is found to increase with [MoO3] [26, 47, 74] and would therefore be lower in CM1 than in CM2.5. Using this theory, the difference between TPS and the glass transition (Tg) is smaller in CM1 than in CM2.5, hence why mixing between and within each phase is limited during cooling before Tg is reached, and the liquid system transitions to an amorphous solid. This could have resulted in an increased clustering of MoO42− anions, which enabled a stage of relaxation and crystal formation with the addition of irradiation energy. This is in contrast to CM2.5, where the lower viscosity phase B had a longer period of time to mix and coalesce, thus diluting MoO42− anions within the amorphous phase. Consequently, increasing [MoO3] appeared to prevent radiation-induced precipitation of CaMoO4 at any fluence.

Phase separation in the borosilicate network following irradiation

The creation of structural disorder following irradiation damage extends to the borosilicate network according to Raman analysis, which showed the creation of smaller or distorted ring structures through the emergence of the D1 and D2 defect bands. This observation implies a process of defect-assisted breaking of large rings and reformation of smaller ones, often with a single type of network former, as has been previously hypothesized to occur [47, 75]. This process of ring cleavage is predicted to increase the dissolution of MoO42− entities by creating more diffusion pathways and by altering the order and size of depolymerized areas within the glass structure.

The growth of the Raman defect bands D1 and D2 and a shift of the R band to higher wavenumbers indicative of smaller ring structures are typical features of irradiated borosilicate glass [3, 41, 44], indicating that the silicate network behaves in a similar manner with and without molybdenum present, though the degree of alteration may vary. Specific intensity changes to the Raman bands assigned to boroxyl rings, B–O− bond elongation, and to three- and four-membered SiO4 rings, which can be used as metrics for phase separation within the Si–O–B network were primarily dependent on the [SiO2]/[B2O3] ratio. Compositionally increasing [B2O3] is known to increase boroxyl rings forming in B-rich domains, as opposed to increasing the Si–O–B network in unirradiated glasses [76]. In this study, increasing [B2O3] was observed to further increase the intensity of the boroxyl ring mode following irradiation, but only marginally alter the intensity of the D2 defect, which saturated at 1 × 1013 ions/cm2. This suggests that B–O··· linkages within the borosilicate network are more susceptible to ion irradiation cleavage, rather than Si–O··· bonds, thus enabling the reformation of additional boroxyl rings as [SiO2]/[B2O3] approached ~ 2.8. In the CM series, additions of MoO3 also affected the boroxyl ring band. Growth and saturation of this band at 1 × 1013 ions/cm2 were observed for CM0 and CM1, while CM2.5 showed damping and saturation for these doses. In contrast, growth of the D2 defect appeared independent of [MoO3]. These results suggest that increasing [MoO3] resulted in the reformation of B–O···Mo linkages, or NBOs on B units, rather than B–O–B bonds following irradiation, while SiO4 remained unperturbed.

Although 11B NMR measurements were not conducted on irradiated samples, it can be assumed that irradiation caused a reduction in the coordination of boron (BO4− → BO3 + NBO), as has been previously observed in many irradiated borosilicate glasses [44, 77]. This would subsequently suggest a reduction in Si–O–B4 bonding [78], and therefore creation of network-modifying cations, which can be correlated with the increased diffusion of Ca atoms following irradiation. It is hypothesized that increasing [MoO3] will accelerate this process by causing an initial growth of [BO3] and boroxyl rings following synthesis, as results in Figs. 4 and 12 suggest, and through the continual competition for charge balancers during irradiation.

It can be concluded from the results that inclusion of 2.5 mol% MoO3 in the amorphous phase for an optimal [SiO2]/[B2O3] ratio (~ 3.2) can limit the extent of single element ring formation following Xe-irradiation and thus the propensity for additional phase separation. Decreasing [SiO2]/[B2O3] to ~ 2.8 would result in the reformation of boroxyl rings and therefore segregation of B-rich domains, while increasing [SiO2]/[B2O3] to > 4.7 would cause growth of three-membered SiO4 rings, and therefore Si-rich domains. This relationship implies a beneficial outcome of radiation damage, in which an initial structural defect created by Mo linkages [70] can limit those created by high-energy ionization, thereby increasing the radiation tolerance of these calcium borosilicate glasses to additional phase separation.

Furthermore, the collective results from Raman and EDS analysis indicate that while many structural changes are observed representative of lingering phase separation between boron and silica-rich regions following irradiation, these modifications saturate around 4 × 1013 to 8 × 1013 ions/cm2. This is not to say that no modifications are occurring past these fluences, as small microstructural changes can still be observed, rather that there are competing processes of damage creation and annealing [3, 36] that result in some preservation of the average short-range order.

Radiation-induced diffusion across interfaces

The greatest modification following irradiation was observed at the interface between phases in these heterogeneous glasses. Changes to morphology and composition suggest that the bonds closer to the A–B and B–C interface are intrinsically weaker, hence why greater alteration is always observed in this region following irradiation. While amorphous systems primarily contain covalent bonds between network formers and ionic bonds between cations and network formers, the bonds between phases are inherently weaker due to changes in atomic ordering [79]. This occurs in binary crystalline-amorphous systems, as well as in some doped polymeric structures where the bonds at the interface show greater sensitivity to changes within the electronic structure or to induced displacements [79, 80]. Analogously, weaker bonds are predicted to form between compositionally and structurally different amorphous phases, making the regions more susceptible to radiation-induced damage and recovery processes.

The mechanism of alteration in these regions is predicted to primarily occur through cross phase diffusion of ions, as ionization is known to increase the mobility of ions [2, 35, 53]. The transport of ions between phases or from the bulk to the surface could be occurring through one of two ways: either the creation of ion channels following the accumulation of defects where ion diffusion is further escalated by the release of dislodged cations following the formation of vacancies [23, 81], or through thermal processes from the added energy of impinging ions. Given that the rate of change in Ca and Mo atomic concentrations decreases with dose and approaches saturation around 8 × 1013 ions/cm2, it indicates the formation of a barrier to diffusion. This can be correlated with defect accumulation or damage recovery processes that subsequently effect diffusion pathways. If diffusion occurred principally through thermal processes, the rate of diffusion would follow Arrhenius laws, instead of saturating. Therefore, the diffusion of atoms is predicted to result primarily from the formation of structural defects, which are hypothesized to be more numerous at the interface between phases, although smaller contributions from thermal energy with a dependence on the energy of the thermal spikes [38] are expected.

Conclusions

Calcium borosilicate glasses with systematically varied [MoO3] and [B2O3] were irradiated with 92 MeV Xe ions to determine how radiation damage would affect the incorporation of molybdenum and the propagation or remediation of phase separation in heterogeneous calcium borosilicates. Five different irradiations were completed with fluences ranging from 5 × 1012 to 1.8 × 1014 ions/cm2 and examined using SEM microscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and XRD. With these analytical techniques, it was determined that Xe-irradiation did not induce precipitation of CaMoO4 in most compositions and for most doses. Where crystallization was detected it was remediated by increasing the irradiation fluence. An increased integration of isolated MoO42− anions by increasing the structural disorder within and between phases was further observed by Raman spectroscopy, indicative of phase separation remediation in the molybdenum environment. Ion diffusion, alterations to the interface between phases, and a reduction in the size and increase in the spatial distribution of immiscible droplets further imply a beneficial integration of phases. In contrast, the formation of smaller ring structures into single atom-type rings within the borosilicate network indicates de-mixing of the Si–O–B network. However, the initiation and extent of de-mixing were mitigated by increasing MoO3 in a glass compositions where [SiO2]/[B2O3] was fixed at ~ 3.2, which suggests that insertion of MoO3 into a calcium borosilicate can limit or in some cases reduce the degree of phase separation between network formers following Xe-irradiation.

Abbreviations

- T PS :

-

Phase separation temperature

- T g :

-

Glass transition temperature

- SON68:

-

Inactive version of French nuclear waste glass R7T7

References

Chu S, Majumdar A (2012) Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. Nature 488:294–303. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11475

Weber WJ, Ewing RC, Angell CA et al (1997) Radiation effects in glasses used for immobilization of high-level waste and plutonium disposition. J Mater Res 12:1946–1978. https://doi.org/10.1557/JMR.1997.0266

Peuget S, Delaye JM, Jégou C (2014) Specific outcomes of the research on the radiation stability of the French nuclear glass towards alpha decay accumulation. J Nucl Mater 444:76–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2013.09.039

Gin S, Guittonneau C, Godon N et al (2011) Nuclear glass durability: new insight into alteration layer properties. J Phys Chem C 115:18696–18706. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp205477q

Frugier P, Martin C, Ribet I et al (2005) The effect of composition on the leaching of three nuclear waste glasses: R7T7, AVM and VRZ. J Nucl Mater 346:194–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2005.06.023

Gras JM, Do Quang R, Masson H et al (2007) Perspectives on the closed fuel cycle—implications for high-level waste matrices. J Nucl Mater 362:383–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2007.01.210

Dunnett BF, Gribble NR, Short R et al (2012) Vitrification of high molybdenum waste. Glass Technol Eur J Glass Sci Technol Part A 53:166–171

Angeli F, Charpentier T, Jollivet P et al (2018) Effect of thermally induced structural disorder on the chemical durability of International Simple Glass. npj Mater Degrad 2:11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-018-0052-3

Lee WE, Ojovan MI, Stennett MC, Hyatt NC (2006) Immobilisation of radioactive waste in glasses, glass composite materials and ceramics. Adv Appl Ceram 105:3–12. https://doi.org/10.1179/174367606X81669

Inagaki Y, Furuya H, Idemitsu K (1992) Microstructure of simulated high-level waste glass doped with short-lived actinides, 238Pu and 244Cm. Mater Res Soc Symp Proc 257:199–206. https://doi.org/10.1557/PROC-257-199

Greer BJ, Kroeker S (2012) Characterisation of heterogeneous molybdate and chromate phase assemblages in model nuclear waste glasses by multinuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Phys Chem Chem Phys 14:7375–7383. https://doi.org/10.1039/c2cp40764g

Vance ER, Davis J, Olufson K et al (2014) Leaching behaviour of and Cs disposition in a UMo powellite glass-ceramic. J Nucl Mater 448:325–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2014.02.024

Haynes WM (2013) CRC handbook of chemistry and physics, 94th edn. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Taurines T, Boizot B (2012) Microstructure of powellite-rich glass-ceramics: a model system for high level waste immobilization. J Am Ceram Soc 95:1105–1111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1551-2916.2011.05015.x

Nicoleau E, Schuller S, Angeli F et al (2015) Phase separation and crystallization effects on the structure and durability of molybdenum borosilicate glass. J Non Cryst Solids 427:120–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2015.07.001

Brehault A, Patil D, Kamat H et al (2018) Compositional dependence of solubility/retention of molybdenum oxides in aluminoborosilicate-based model nuclear waste glasses. J Phys Chem B 122:1714–1729. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b09158

Caurant D, Majérus O, Fadel E et al (2007) Effect of molybdenum on the structure and on the crystallization of SiO2–Na2O–CaO–B2O3 glasses. J Am Ceram Soc 90:774–783. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1551-2916.2006.01467.x

Horneber A, Camara B, Lutze W (1982) Investigation on the oxidation state and the behaviour of molybdenum in silicate glass. MRS Proc Sci Basis Nucl Waste Manag V 11:279–288. https://doi.org/10.1557/PROC-11-279

Camara B, Lutze W, Lux J (1979) An investigation on the valency state of molybdenum in glasses with and without fission products. In: Northrup CJM (ed) Advances in nuclear science and technology: scientific basis for nuclear waste management. Springer, Boston, pp 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-3839-0_11

Short RJ, Hand RJ, Hyatt NC, Möbus G (2005) Environment and oxidation state of molybdenum in simulated high level nuclear waste glass compositions. J Nucl Mater 340:179–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2004.11.008

Greaves GN, Ngai KL (1995) Reconciling ionic-transport properties with atomic structure in oxide glasses. Phys Rev B 52:6358–6380. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.52.6358

Caurant D, Majérus O, Fadel E et al (2010) Structural investigations of borosilicate glasses containing MoO3 by MAS NMR and Raman spectroscopies. J Nucl Mater 396:94–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2009.10.059

Patel KB, Boizot B, Facq SP et al (2017) β-Irradiation effects on the formation and stability of CaMoO4 in a soda lime borosilicate glass ceramic for nuclear waste storage. Inorg Chem 56:1558–1573. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b02657

Schmidt M, Heck S, Bosbach D et al (2013) Characterization of powellite-based solid solutions by site-selective time resolved laser fluorescence spectroscopy. Dalton Trans 42:8387. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3dt50146a

Calas G, Le Grand M, Galoisy L, Ghaleb D (2003) Structural role of molybdenum in nuclear glasses: an EXAFS study. J Nucl Mater 322:15–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3115(03)00277-0

Magnin M, Schuller S, Mercier C et al (2011) Modification of molybdenum structural environment in borosilicate glasses with increasing content of boron and calcium oxide by 95Mo MAS NMR. J Am Ceram Soc 94:4274–4282. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1551-2916.2011.04919.x

Chouard N, Caurant D, Majérus O et al (2015) Effect of MoO3, Nd2O3, and RuO2 on the crystallization of soda–lime aluminoborosilicate glasses. J Mater Sci 50:219–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-014-8581-9

Schuller S, Pinet O, Grandjean A, Blisson T (2008) Phase separation and crystallization of borosilicate glass enriched in MoO3, P2O5, ZrO2, CaO. J Non Cryst Solids 354:296–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2007.07.041

Henry N, Deniard P, Jobic S et al (2004) Heat treatments versus microstructure in a molybdenum-rich borosilicate. J Non Cryst Solids 333:199–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2003.09.055

Kawamoto Y, Clemens K, Tomozawa M (1981) Effects of MoO3 on phase separation of Na2O–B2O3-SiO2 glasses. J Am Ceram Soc 64:292–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1151-2916.1981.tb09605.x

Ishiguro K, Kawanishi N, Nagaki H, Naito A (1982) Chemical states of molybdenum in radioactive waste glass (PNCT-N–831-82-01). Annual Progress Report of Power Reactor and Nuclear Fuel Development Corporation, Tokai Works, Japan

Martineau C, Michaelis VK, Schuller S, Kroeker S (2010) Liquid-liquid phase separation in model nuclear waste glasses: a solid-state double-resonance NMR study. Chem Mater 22:4896–4903. https://doi.org/10.1021/cm1006058

Boizot B, Petite G, Ghaleb D, Calas G (1998) Radiation induced paramagnetic centres in nuclear glasses by EPR spectroscopy. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res Sect B Beam Interact Mater Atoms 141:580–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-583X(98)00102-5

Peng HB, Sun ML, Yang KJ et al (2016) Effect of irradiation on hardness of borosilicate glass. J Non Cryst Solids 443:143–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2016.04.027

Mir AH, Toulemonde M, Jegou C et al (2016) Understanding and simulating the material behavior during multi-particle irradiations. Sci Rep 6:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30191

Charpentier T, Martel L, Mir AH et al (2016) Self-healing capacity of nuclear glass observed by NMR spectroscopy. Sci Rep 6:25499. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25499

Hirsch EH (1980) A new irradiation effect and its implications for the disposal of high-level radioactive waste. Science 209:1520–1522. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7433973

Toulemonde M, Paumier E, Dufour C (1993) Thermal spike model in the electronic stopping power regime. Radiat Effects Defects Solids 126:201–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/10420159308219709

Nullmeyer BR, Kwon JW, Robertson JD, Garnov AY (2018) Self-healing effects in a semi-ordered liquid for stable electronic conversion of high-energy radiation. Sci Rep 8:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30815-w

Turcotte RP, Roberts FP (1977) Phase behavior and radiation effects in high level waste glass (BNWL-SA-6168). PNNL, Battelle-Northwest

de Bonfils J, Peuget S, Panczer G et al (2010) Effect of chemical composition on borosilicate glass behavior under irradiation. J Non Cryst Solids 356:388–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2009.11.030

Maugeri EA, Peuget S, Staicu D et al (2012) Calorimetric study of glass structure modification induced by α decay. J Am Ceram Soc 95:2869–2875. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1551-2916.2012.05304.x

Delaye J-M, Peuget S, Bureau G, Calas G (2011) Molecular dynamics simulation of radiation damage in glasses. J Non Cryst Solids 357:2763–2768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2011.02.026

Mendoza C, Peuget S, Charpentier T et al (2014) Oxide glass structure evolution under swift heavy ion irradiation. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B Beam Interact Mater Atoms 325:54–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2014.02.002

Mir AH, Monnet I, Boizot B et al (2017) Electron and electron-ion sequential irradiation of borosilicate glasses: impact of the pre-existing defects. J Nucl Mater 489:91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2017.03.047

Ziegler JF, Ziegler MD, Biersack JP (2010) SRIM—the stopping and range of ions in matter (2010). Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B Beam Interact Mater Atoms 268:1818–1823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2010.02.091

Patel KB, Boizot B, Facq SP et al (2017) Impacts of composition and beta irradiation on phase separation in multiphase amorphous calcium borosilicates. J Non Cryst Solids 473:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2017.06.018

Yazawa T, Kuraoka K, Akai T et al (2000) Clarification of phase separation mechanism of sodium borosilicate glasses in early stage by nuclear magnetic resonance. J Phys Chem B 104:2109–2116. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp993416b

Möncke D, Tricot G, Winterstein-Beckmann A, Wondraczek L, Kamitsos EI (2015) On the connectivity of borate tetrahedra in borate and borosilicate glasses. Eur J Glass Sci Technol Part B Phys Chem Glass 56:203–211. https://doi.org/10.13036/17533562.56.5.203

Manghnani MH, Hushur A, Sekine T et al (2011) Raman, Brillouin, and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopic studies on shocked borosilicate glass. J Appl Phys 109:113509. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3592346

Tricot G (2016) The structure of Pyrex glass investigated by correlation NMR spectroscopy. Phys Chem Chem Phys 18:26764–26770. https://doi.org/10.1039/c6cp02996e

Du LS, Stebbins JF (2003) Solid-state NMR study of metastable immiscibility in alkali borosilicate glasses. J Non Cryst Solids 315:239–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3093(02)01604-6

Boizot B, Petite G, Ghaleb D et al (2000) Migration and segregation of sodium under β-irradiation in nuclear glasses. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B Beam Interact Mater Atoms 166–167:500–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-583X(99)00787-9

Neuville DR, Cormier L, Boizot B, Flank AM (2003) Structure of β-irradiated glasses studied by X-ray absorption and Raman spectroscopies. J Non Cryst Solids 323:207–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3093(03)00308-9

Furukawa T, White WB (1981) Raman spectroscopic investigation of sodium borosilicate glass structure. J Mater Sci 16:2689–2700. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00552951

Walrafen GE, Samanta SR, Krishnan PN (1980) Raman investigation of vitreous and molten boric oxide. J Chem Phys 72:113–120. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.438894

Hehlen B, Neuville DR (2015) Raman response of network modifier cations in alumino-silicate glasses. J Phys Chem B 119:4093–4098. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp5116299

Krogh-Moe J (1969) The structure of vitreous and liquid boron oxide. J Non Cryst Solids 1:269–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3093(69)90025-8

Konijnendijk WL, Stevels JM (1975) The structure of borate glasses studied by Raman scattering. J Non Cryst Solids 18:307–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3093(75)90137-4

Manara D, Grandjean A, Neuville DR (2009) Advances in understanding the structure of borosilicate glasses: a raman spectroscopy study. Am Miner 94:777–784. https://doi.org/10.2138/am.2009.3027

Wang X, Panczer G, de Ligny D et al (2014) Irradiated rare-earth-doped powellite single crystal probed by confocal Raman mapping and transmission electron microscopy. J Raman Spectrosc 45:383–391. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrs.4472

Frost RL, Bouzaid J, Butler IS (2007) Raman spectroscopic study of the molybdate mineral szenicsite and compared with other paragenetically related molybdate minerals. Spectrosc Lett 40:603–614. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrs.820

Lee SK, Stebbins JF (2003) Nature of cation mixing and ordering in Na–Ca silicate glasses and melts. J Phys Chem B 107:3141–3148. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp027489y

Calas G, Galoisy L, Cormier L et al (2014) The structural properties of cations in nuclear glasses. Procedia Mater Sci 7:23–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mspro.2014.10.005

Morey GW, Ingerson E (1937) The melting of danburite: a study of liquid immiscibility in the system, CaO–B2O3–SiO2. Am Miner 22:37–47

Mazurin O, Porai-Koshits EA (1984) Phase separation in glass, vol 5, 1st edn. Elsevier, North Holland

Vogel W (1994) Glass chemistry, 2nd edn. Springer, Berlin. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-78723-2

Smedskjaer MM, Mauro JC, Youngman RE et al (2011) Topological principles of borosilicate glass chemistry. J Phys Chem B 115:12930–12946. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp208796b

Takahashi S, Neuville DR, Takebe H (2015) Thermal properties, density and structure of percalcic and peraluminus CaO–Al2O3–SiO2 glasses. J Non Cryst Solids 411:5–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2014.12.019

Tricot G, Ben Tayeb K, Koudelka L et al (2016) Insertion of MoO3 in borophosphate glasses investigated by magnetic resonance spectroscopies. J Phys Chem C 120:9443–9452. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b02502

Abdel-Rehim A (2004) Thermal analysis and X-ray diffraction of synthesis of scheelite. J Therm Anal Calorim 64:557–569. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011577903726

Ewing RC, Meldrum A, Wang L, Wang S (2000) Radiation-induced amorphization. Rev Miner Geochem 39:319–361. https://doi.org/10.2138/rmg.2000.39.12

Hobbs LW, Clinard FW, Zinkle SJ, Ewing RC (1994) Radiation effects in ceramics. J Nucl Mater 216:291–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3115(94)90017-5

Schuller S, Pinet O, Penelon B (2011) Liquid–liquid phase separation process in borosilicate liquids enriched in molybdenum and phosphorus oxides. J Am Ceram Soc 94:447–454. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1551-2916.2010.04131.x

Yang T, Gao Y, Huang X et al (2011) The transformation balance between two types of structural defects in silica glass in ion-irradiation processes. J Non Cryst Solids 357:3245–3250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2011.05.017

Liu H, Youngman RE, Kapoor S et al (2018) Nano-phase separation and structural ordering in silica-rich mixed network former glasses. Phys Chem Chem Phys 20:15707–15717. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8cp01728j

Peuget S, Maugeri EA, Charpentier T et al (2013) Comparison of radiation and quenching rate effects on the structure of a sodium borosilicate glass. J Non Cryst Solids 378:201–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2013.07.019

Yuan W, Peng H, Sun M et al (2017) Structural origin of hardness decrease in irradiated sodium borosilicate glass structural origin of hardness decrease in irradiated sodium borosilicate glass. J Chem Phys 147:7. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5004220

Ayache J, Beaunier L, Boumendil J et al (2010) Introduction to materials. In: Sample preparation handbook for transmission electron microscopy. Springer, New York. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-98182-6

Yu L, Raj R (2015) On the thermodynamically stable amorphous phase of polymer-derived silicon oxycarbide. Sci Rep 5:14550. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep14550

Griscom DL (2011) Trapped-electron centers in pure and doped glassy silica: a review and synthesis. J Non Cryst Solids 357:1945–1962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2010.11.011

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the EMIR network for irradiation time. They would also like to acknowledge the assistance of several members in the Department of Earth Sciences (Giulio I. Lampronti, Sébastien P. Facq, Iris Buisman, Robin Clarke, and Chris Parish) and those from the Department of Material Science and Metallurgy (Lata Sahonta, Rachel Olivier) that aided in access to facilities and sample preparation, as well as training on analytical equipment. This work has been funded by the University of Cambridge, Department of Earth Sciences and EPSRC (Grant No. EP/K007882/1) for an IDS, with additional financial support provided by FfWG and the Cambridge Philosophical Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Patel, K.B., Peuget, S., Schuller, S. et al. Swift heavy ion-irradiated multi-phase calcium borosilicates: implications to molybdenum incorporation, microstructure, and network topology. J Mater Sci 54, 11763–11783 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-019-03714-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-019-03714-2