Abstract

A Type 316H austenitic stainless steel component containing Cr and impurity element-rich localised regions arising from component fabrication was aged for a prolonged period during service at a temperature of approximately 550 °C. These regions make up approximately 5% of the total volume of the microstructure. Previous work has shown that these regions contain ferrite and carbide precipitates and a finer austenite grain size than the adjacent matrix. The present study has used high-resolution transmission electron microscopy combined with compositional microanalysis to show that these regions have a highly complex microstructure containing G phase, chi phase and intragranular γ′ precipitates within the austenite grains. There is phosphorus migration to the chi austenite phase boundary, and the basis for this equilibrium impurity segregation is discussed. A Cr-depleted region was observed surrounding the chi phase precipitates, and the impact of this on the other precipitates is considered. The diversity of precipitates in these Cr-rich regions means that they behave significantly differently to the bulk material under long-term creep conditions leading to preferred nucleation and growth of creep cavities and the formation of localised creep cracks during service.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The microstructure of an austenitic stainless steel has a significant role in controlling the physical, chemical and mechanical properties. In the case of high temperature, ~ 550 °C, nuclear electrical power generating plant subject to extended periods of operating, > 105 h, changes in the microstructure can have a significant influence on the overall service life. For example, the presence of secondary phase precipitates, such as ferrite, has the potential to significantly alter the creep properties by changing the behaviour of creep damage accumulation [1,2,3,4,5]. The evolution of secondary phases during thermal ageing of Type 316 austenitic stainless steels has been observed experimentally [5,6,7,8,9] and predicted thermodynamically [10], driven by a favourable Gibbs energy [11]. These precipitates will nucleate at discrete sites within the overall microstructure and grow over time. Austenitic stainless steels are known to form a wide range of precipitates depending on the specific composition and thermo-mechanical history. Indeed, up to 18 different precipitate types have been variously identified after prolonged ageing [7], leading to highly complex microstructures. Precipitates commonly found include both α- and δ-ferrite, various carbides [8], and complex phases such as sigma phase, R phase and G phase. One of the less encountered precipitates is G phase, a silicon containing FCC intermetallic phase (a = 1.115–1.120 nm [12]) with a nominal composition observed in austenitic stainless steels [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] of (Ni/Fe/Cr)16(Nb/Ti)6Si6 [12]. By comparison, in duplex stainless steels [12, 21, 22] the composition is (Fe/Ni)16(Mn/Cr)6Si7 [19]. Other studies have found that substitution of Mo for Ni is possible [14, 23]. G phase precipitates form within the ferrite regions of duplex [21, 22] and nominally austenitic stainless steels (e.g. Type 300 series austenitic steels) [13, 15, 16, 19] during ageing within the temperature range of 250–500 °C [12, 14, 22]. This phase typically nucleates and grows at austenite grain boundaries [21, 24], and/or at austenite–α-ferrite phase boundaries but in the latter case it has a cube-on-cube orientation relationship with the ferrite [19, 21]. G phase evolution in austenite is associated with exposure to higher temperatures, within a nominal range of 500–800 °C [13], where the kinetics have been purported to be controlled by the rate of Si diffusion [21]. Lower ageing temperatures in austenitic stainless steels favour austenite grain boundary precipitation of G phase [12, 13], whilst intragranular precipitation is observed at higher temperatures [12]. Steels with high volume fractions of G phase have been found to be embrittled [19, 25] when subjected to room temperature fracture, and as such the phase promotes intergranular fracture.

Chi phase is a BCC intermetallic phase (a = 0.881–0.895 nm [12]) the precipitation of which only occurs in Mo- or Ti-containing stainless steels [12, 26]. Depending on the relative concentrations of Mo and Ti, the composition of the chi phase ranges from (Fe/Ni)36Cr12Mo10 to (Fe/Ni)36Cr12Mo3Ti7 [12, 24, 26,27,28], and there is potential for substitution of other elements [28]. The composition of chi phase is frequently likened to that of sigma phase, with the principle differences being the solubility of carbon [12, 26] and higher concentrations of molybdenum [26, 29, 30]. Chi phase has been observed to nucleate and grow preferentially into the ferrite regions of dual phase (austenite-ferrite) steels [26, 29,30,31,32], at grain boundaries of δ-ferrite [26, 32], at austenite–δ-ferrite grain edges and nodes [32] and austenite–δ-ferrite phase boundaries [29, 30, 32]. This preference has been linked to the greater concentrations of Cr and Mo present in ferrite, and the higher rate of diffusion of these BCC elements through the ferrite (BCC) as opposed to the austenite (FCC) [31]. In addition, precipitation of chi phase has been observed associated with M23C6 carbide precipitates [33]. The presence of chi phase precipitates in general decreases room temperature fracture toughness and reduces corrosion resistance [12, 32], although it has been observed to not significantly modify creep deformation or damage accumulation behaviour of austenitic stainless steel [27, 34].

The degree of deformation (reduction in cross section) which occurs during the fabrication of a component can have a significant role in the evolution of subsequent microstructure. Highly worked thin cross-sectional components, such as tubes, tend to be subject to more severe deformation than thicker walled components such as headers. More severe deformation removes heterogeneous casting features arising from the original dendritic structure of the cast ingot [35]. The presence of localised elementally enriched regions in the microstructure can have a significant impact on subsequent precipitation within the component, as most secondary phases are composition dependant [12, 24]. When subject to smaller amounts of fabrication, deformation localised regions with a significantly different composition can remain. The consequences are that these localised variations in composition lead to an austenitic stainless steel with a non-uniform and complex microstructure when subjected to the long-term ageing typically encountered during service.

In addition to fabrication effects, precipitation is significantly influenced by cast-to-cast variation. Steel for plant construction will be supplied to a given specification, which consists of a range of acceptable compositions for specified elements. As such notionally identical components made of “Type 316H” steel may have different specific compositions. This can be further influenced by the fabrication effects already discussed. Outside of the monitored elements, there may also be disparities in trace impurity levels between both casts and manufacturers. The net effect of these variations in composition is that they can lead to differences in secondary phase precipitation. Thus, two components of different casts aged for the same time at the same temperature can have differences in the phases evolved and the volume fraction of these phases.

In this paper, we describe the microstructure of fine-grained, Cr-enriched regions arising as a consequence of failure to homogenise the original cast microstructure during the thermo-mechanical fabrication of an ex-service Type 316 austenitic stainless steel component subject to a post-service heat treatment. The heterogeneous microstructure is described together with the influence on the subsequent precipitation. The precipitates have been characterised using high spatial resolution electron optical techniques combined with STEM-EDX microanalysis. The precipitates identified are discussed with respect to the thermodynamics and kinetics of precipitation.

Materials and methods

The material sample studied was 25 mm × 10 mm × 10 mm of Type 316H austenitic stainless steel, cut from the attachment weldment region of an advanced gas-cooled reactor (AGR) boiler header (provided by EDF Energy Ltd.). During service, the specimen experienced 65015-h operation in the temperature range 490–530 °C, followed by a post-service laboratory heat treatment of 22100 h at 550 °C to simulate the effects of further ageing. The post-manufacture thermo-mechanical history of the specimen is shown schematically in Fig. 1, and the composition of the specimen is given in Table 1. During manufacture, the material was solution treated for 3 h at 1050 °C, followed by a water quench. The material is known to contain approximately 0.2–0.5 vol% mixed δ- and α-ferrite following step (I) [5] which increased to approximately 2 vol% δ- and α-ferrite following the laboratory heat treatment, step (II) [5]. During service, the conditions were such that the specimen experienced creep, resulting in the formation of creep cavities and a significant creep crack [5].

Schematic diagram showing the thermo-mechanical history of the specimen. The outages in step (I) are representative and as such are not to scale. Note the horizontal axis intersects at room temperature. After Warren et al. [5]

Specimens were consecutively polished with silicon carbide papers and diamond pastes to obtain a 0.25-μm surface finish. Additional polishing using 0.1-μm colloidal silica was required to produce a suitably high-quality surface for electron backscatter diffraction to identify the fine-grained, Cr-enriched, residual casting regions [5], from which transmission electron microscopy (TEM) liftouts were prepared. Electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) analysis was performed in a Zeiss SIGMA FEG-SEM, fitted with a high-speed camera (DigiView 3). All EBSD maps were collected with the SEM operating at 30 kV, and the specimen tilted by 70 degrees to the horizontal. Data were collected using orientation image mapping (OIM) software (Ametek, Utah, USA).

Liftouts were prepared from the specimen by gallium ion milling using a FEI Helios Nanolab 600i “Dual beam” SEM/FIB workstation. The liftouts were given a lower energy 5-kV ion mill at the end of the process to reduce the surface damage, which was confirmed by observation in the TEM [36]. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) were performed using a JEOL-ARM 200CF with a Cs probe corrector, operating at 200 kV. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (STEM-EDX) was performed using a 100-mm2 JEOL Centurion detector and NSS version 3.2 analysis software. Electron energy loss spectrometry measurements were made with a Gatan GIF Quantum 965 ER detector with the results process with the Digital Micrograph software.

Results

Previous studies on the ex-service Type 316H material by Chen et al. [37] and Warren et al. [5] identified localised regions with a fine grain size enriched in Cr, and impurity elements arising from the initial casting process [5, 37], Fig. 2a. The bulk of the microstructure comprises austenite grains with diameters of 20–100 µm [5], together with a distribution of approximately 2% by area ferrite and other intragranular precipitates [5]. Hence, subsequent fabrication, solution treatment and long-term thermal ageing had not fully removed the initial casting microstructure and the associated local composition fluctuations [5]. When the residual regions were investigated using EBSD, the grains contained a large number of small austenite grains (< 20 µm) with low angle sub-boundaries [5], and a much greater proportion of ferrite and chi phase precipitates than in the bulk of the material [5], Fig. 2b. The chromium-enriched regions can clearly be seen in the composition map, Fig. 2c.

Characterisation of the ex-service Type 316H specimen. a A region from Chen et al’s optical micrograph, showing the distribution of fine-grained austenite/ferrite/M23C6 carbide regions [41], b EBSD phase map for a localised Cr-enriched region, with austentite in red and ferrite in green. c Cr Kα EDX map showing the distribution of Cr-enriched regions within a region

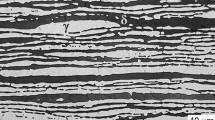

High-resolution TEM analysis of liftouts selected from the local high Cr regions revealed a range of precipitates. Compositions and lattice parameters for the bulk austenite and ferrite precipitates are summarised in Table 2. In many cases, the measured compositions of the phases show significant divergence from those given in previous studies on Type 316H austenitic stainless steels with a more uniform microstructure. A TEM bright-field image showing chi phase, G phase and γ′ is shown in Fig. 3.

TEM bright-field image showing a γ′ precipitate-depleted region around a chi phase precipitate with associated G phase precipitate. The partial circle of different contrast on the left of the image is due to the relative positioning of the specimen with respect to the amorphous carbon support. Measurements for quantification were taken from precipitates sited over holes in the support grid

Localised precipitation

In this section, we consider in detail each of the long-term ageing-induced precipitates identified in the 4 TEM liftouts cut from the localised Cr-enriched regions.

Chi (χ) phase

Faceted precipitates of up to 1 μm equivalent diameter, at the austenite–austenite grain boundaries were identified as chi phase from the BCC crystal structure and lattice parameter (~ 0.8 nm), by electron diffraction. Figure 4 shows a typical chi phase [−113] electron diffraction pattern recorded from this specimen. An atomic resolution image, of an austenite–chi phase boundary is shown in Fig. 5 where the lattice spacing in the austenite is 0.17 nm, and the chi phase is 0.41 nm. The periodic variations in contrast along the interface are mismatch dislocations to accommodate lattice differences, and associated strain, between the two phases.

Selected area diffraction pattern observed from the chi phase, precipitate shown in Fig. 3

The composition of the chi phase precipitates was measured from seven precipitates using EDX microanalysis, giving an average measured composition of approximately (Fe/Ni)15Cr26Mo. This is a distinct difference compared with the composition reported in previous studies between (Fe/Ni)36Cr12Mo10 and (Fe/Ni)36Cr12Mo3Ti7 [12, 24, 26,27,28]. The composition measured at the austenite–chi phase boundary, Fig. 6a, shows the expected distribution of primary alloying elements (Cr, Fe) between the phases. In Fig. 6b, the lower concentration elements Ni, Si and S are shown. In particular, Si is associated with the chi phase. An increase was observed in the carbon signal due to deposition of carbon-containing contamination during the measurement, an increase with time rather than phase dependence. There is a distinct P peak of 0.68 wt% at the position of the phase boundary, Fig. 6c. The electron beam will be dispersed by the foil, so this value may be an underestimate of the true composition. However, the foil is < 100 nm and the incident electron probe is approximately 0.1 nm dia. so the extent of the beam dispersion will be small. In such cases, it is appropriate to adopt the simple correction to the measured concentration, C, given by Faulkner et al. [38] based on the more rigorous analysis proposed by Doig et al. [39]:

where C0 is the solute concentration in the austenite matrix, Cb is the actual solute concentration at the boundary, xd is the location of the beam relative to the boundary (using sub-pixel scanning means this can be approximated as zero as the beam will raster across the boundary within the relevant pixel), d0 is the width of the solute layer at the boundary (assumed as 1 nm due to equilibrium segregation) and σ the standard deviation of the electron probe distribution [39]:

where B is the electron probe diameter calculated using Eq. 1. Using this conversion factor gives the true concentration of phosphorus at the austenite–chi phase boundary as approximately 2.0 wt%. No corresponding change in any alloying or other impurity elements was observed.

STEM-EDX line scans across an austenite–chi phase boundary. a The full range for Cr and Fe, b the low weight percentage elements, Ni, Si and S, c the uncorrected measurement of phosphorus enrichment at the interphase boundary. Errors are taken from the standard deviation of the data. Profiles were recorded at a dwell of 5 s per pixel, and 6 repeats, to give a total of 30 s per pixel

G phase

The G phase formed as faceted precipitates of ~ 50 nm equivalent diameter closely associated with the chi phase precipitates, Fig. 7a. When the chi phase precipitate was orientated close to a zone axis, Fig. 7b, the G phase precipitates were orientated on a [110] zone axis (dark contrast in the image). In addition, electron diffraction of the G phase, Fig. 7c, reveals a fcc crystal structure with a lattice parameter of 1.14 nm, with atomic resolution lattice images of this phase are shown in Fig. 7d. High spatial resolution STEM-EDX microanalysis undertaken on thirteen of these nominally G phase precipitates reveal the presence of Fe, Ni, Cr and Si, Fig. 8. The composition corresponds to (Fe,Ni,Mo)16(Cr)6Si2. Previous workers have reported various compositions of the G phase in a range of austenitic stainless steels: a typical example for the compositions is (Ni, Fe, Mo, Cr)16(Nb, Mn, Cr, Ti)6Si6 or 7 [12, 14, 19, 23]. The crystal structure of the G phase detected in the current specimen is consistent with previous observations, although the lattice parameter is slightly smaller (a = 1.115–1.120 nm [12]). However, the phase appears to have a significantly lower silicon content compared to other studies [12, 14, 19, 23]. It is possible that this difference accounts for the smaller lattice parameter of the crystal lattice compared to previous studies. In this case, 92% of the G phase precipitates were found on the austenite side of austenite–ferrite and austenite–chi phase boundaries, with the remaining precipitates sited on ferrite–ferrite precipitate boundaries. It has been noted that frequently impurity P is associated with G phase precipitates [40], but it was not unambiguously confirmed for the present precipitates.

G phase precipitates associated with chi phase in the ex-service + 22000-h aged Type 316H austenitic stainless steel. a STEM image of G phase adjoining chi phase precipitates in an austenite matrix and b TEM image showing the close orientation relationship between the chi phase precipitate and its adjoining G phase precipitate in the austenite matrix. The blue box corresponds to the region in a. c Selected area diffraction pattern from a typical G phase precipitate, showing additional diffraction spots arising from matrix and chi phase precipitates. d atomic resolution STEM images of G phase crystal lattice

Intragranular γ′ precipitates

Small cubic intragranular precipitates within the austenite grains were also identified in the Cr-rich regions, Fig. 9.

These precipitates typically showed a degree of alignment, consistent with a fixed orientation relationship with the austenite grain. An atomic resolution HRTEM image of two of these ordered precipitates is shown in Fig. 10. Characterising the FFT from one of the precipitates, derived from the HRTEM images, Fig. 10, gives an atomic spacing consistent with a lattice parameter of between 0.331 and 0.337 nm. Microanalysis composition measurements taken from four precipitates were averaged to give the composition in Table 3. This lattice parameter and composition correlates well with γ′.

Spatial relationships between chi phase, G phase and γ′

Across the majority of the TEM liftouts, it was noted that within the Cr-enriched regions the phases had distinct relationships with each other. Chi phase precipitates were associated with G phase precipitates, although G phase was associated with both chi phase and ferrite precipitates (not shown). The austenite surrounding the chromium-rich chi phase precipitates was depleted of intragranular γ′, Fig. 3, consistent with local depletion of the austenite in chromium.

The austenite–chi phase grain boundary composition line scan in Fig. 6 shows no difference in Cr distribution in the austenite within 20 nm of the chi phase boundary. However, if the compositional analysis is extended further into the neighbouring grains, Fig. 11a, it becomes clear that the austenite surrounding the chi precipitate is relatively depleted in chromium compared to the bulk of the austenite grain. An electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) line scan across the same chi phase precipitate also shows chromium depletion, Fig. 11b.

Composition analysis across a chi phase precipitate. a Shows an EDX line scan across a chi phase precipitate and b EELS line scan across a chi phase precipitate, including several γ′ precipitates in the austenite (denoted by the spikes in Cr). Note the Cr-depleted region in the austenite within 200 nm of the chi phase boundary

Discussion

The ex-service Type 316H stainless steel has a very complex microstructure arising from the fabrication history which does not introduce sufficient deformation to homogenise the microstructure and therefore leaves local regions of different composition arising from the original cast ingot [5]. TEM liftouts were cut from these high Cr fine-grained regions identified by Chen [41] and Warren et al. [5] reveal that a complex mix of precipitates arises as a consequence of long-term service at temperatures of ~ 550 °C, including α-ferrite, chi phase, γ′ and G phase, as summarised in Tables 2 and 3, and shown schematically in Fig. 12.

The composition of the austenite in the bulk regions is 17.5% Cr and 12.05% Ni whilst the main secondary phase precipitate is M23C6 carbide [37]. In the localised Cr-enriched residual casting regions, the mean bulk Cr value is 18.0%, Mo is 0.65% and Ni is 9.89%. This significant difference in behaviour can provide an insight into the role some elements play on long-term precipitate evolution.

In general, the current understanding of the precipitation behaviour of secondary phases in austenitic stainless steels is based upon the consideration that the material is homogenous. Few studies consider prolonged ageing at temperatures around 500 °C and the interaction between evolving phases. Weiss and Stickler’s time–temperature–precipitation diagram for aged Type 316H predicts only M23C6 carbide formation under present ageing conditions [9].

The CALPHAD model developed by Yang and Busby [10] considers a steel of similar composition to that used in this study, with comparable Ni and Si levels. This predicts that within the parent austenite, sigma phase, Laves phase, M23C6 carbide and an iron-rich ferrite phases precipitate under equilibrium conditions at 550 °C. G phase precipitates are not predicted at any temperature, whilst chi phase formation is predicted only for temperatures that exceed 750 °C and γ′ (Ni3Si) formation for temperatures under 400 °C [10]. These predictions differ significantly from the observed phases that precipitated in the localised regions of the present material that are higher in concentrations of Cr. Based on these studies and those discussed in the introduction, the proposed precipitation sequence is:

-

(Microstructure as fabricated (AF): Austenite + δ-ferrite + M23C6)

-

→ AF + G phase + M23C6

-

→ AF + G phase + M23C6 +”High Fe” α-ferrite [5] + α-ferrite + chi phase

-

→ AF + G phase + M23C6 +”High Fe” α-ferrite [5] + α-ferrite + chi phase +γ′

Given the thermo-mechanical history of the samples, the evolution of G phase at austenite grain boundaries would be expected [12, 19]. Previous studies have not shown G phase associated with chi phase precipitates. Due to the history of the material, it is unclear whether the G phase evolved from the chi phase or whether the G phase evolved from a ferrite–precipitate which subsequently transformed into chi phase. Previous studies have noted the compositional similarity between chi phase and sigma phase [12, 26], whilst G phase has been observed in association with sigma phase—as such, this correlation appears reasonable. Likewise, G phase is known to form from ferrite [13, 19] so this also represents a plausible possibility. Further work is required to clarify this. The measured lattice parameter correlates with other observations of G phase (FCC, a = 1.115–1.12 nm [12]). If the G phase precipitates in the ex-service steel are normalised for Fe, Ni and Mo, an average measured composition becomes (Fe, Ni, Mo)16(Cr)6Si2. A theoretical composition for G phase has been given as (Ni, Fe, Cr)16(Nb, Ti)6Si6 [12]; however, substitution of several alloying elements has previously been observed such that a more representative combination would be (Ni, Fe, Mo, Cr)16(Nb, Mn, Cr, Ti)6Si6 or 7 [14, 19, 23] or as generalised by Sourmail to be A16D6C7 where A and D are transition elements and C is a group IV element [24]. Although the ratio of alloying elements shown in Table 3 is comparable to that observed in G phase, the silicon level is significantly lower. The ex-service material has a bulk Si content lower than the steels used in many studies on G phase, which is reflected in the low ferrite to austenite Si ratio; ~ 0.6 wt% in ferrite; and ~ 0.8 wt% in austenite. No significant elemental segregation was observed at the austenite–G phase boundary. Based on observations, both the austenite–chi phase and the austenite–ferrite interfaces provide nucleation sites. However, chi phase presents a preferred nucleation site due to the close lattice parameter matching with the nucleating G phase (ferrite a = 0.285–0.289 nm, chi phase a = 0.795–0.845 nm, austenite a = 0.358 and G phase a = 1.115–1.12 nm).

Chi phase precipitates were frequently observed and were typically associated with G phase precipitates. It is unclear at what stage of the thermal ageing the chi phase precipitates in the material evolved—the closest comparable literature observation to the specimen (Type 316 N steel/85000 h creep test/550 °C) [42] suggests that in the present case the chi phase precipitates would have formed during the additional 22000 h post-service ageing. However, given that chi phase is typically formed in the high Cr δ-ferrite rich regions, duplex steels or Type 300 series weld metal may provide a better basis for comparison. Assuming this to be the case, there have been observations of chi phase after only 5000 h at 500 °C [31] and rapid chi phase precipitation at 600 °C [30, 34, 43] suggests that evolution will have occurred during the service life of the material. Hence, the initial nucleation of chi phase occurs during service; however, further precipitates may nucleate and grow during the post-service heat treatment. Studies have frequently observed the transformation of δ-ferrite to chi phase [26, 29, 31, 32] and as such chi phase precipitates may be considered to mark the sites of former ferrite precipitates.

The observed P enrichment at the austenite–chi phase boundary is consistent with studies by Chen [41] showing the presence of P on low-temperature fracture surfaces. This enrichment was attributed to the segregation to the austenite–ferrite interphase boundary [41]; however, the current work shows that it is the austenite–chi phase boundaries that are enriched in P. The favourability of interphase boundary equilibrium segregation can be assessed by using the free energy of segregation of phosphorus \( \Delta G_{P} \), which can be calculated in austenite and chi phase using the equation:

where ΔHP is the standard molar enthalpy of phosphorus segregation, T is the temperature and ΔSP is the standard molar entropy of phosphorus segregation. Ševc et al. [44] determined the ΔHP and ΔSP of phosphorus in a Type 304 as 14.1 ± 8.3 kJ/mol and 15.0 ± 8.5 J/(mol k), respectively. These data correlate well with the Paju and Grabke measurements of segregation in a Fe–P binary alloy at austenite temperatures [45]. ΔHP and ΔSP for phosphorus segregation in chi phase are not known, and as such the values for segregation in ferrite have been used as a first approximation. These were determined as − 34.3 kJ/mol and 21.5 J/mol, respectively [46, 47]. Using these values in Eq. 3, it is possible to calculate the free energy of segregation of P in austenite as -25.7 kJ/mol and in ferrite (approximating chi phase) as − 51.0 kJ/mol. P segregation to the austenite–chi phase boundary, Fig. 5, will be more favourable than that predicted for an equivalent austenite–ferrite boundary as the greater lattice mismatch between the phases will provide more favourable sites for P (chi phase a = 0.795–0.845 nm, austenite a = 0.358 nm and ferrite a = 0.285–0.289 nm).

Using the modified Langmuir–McLean formalism and considering site competition [44, 46] together with the measured compositions for austenite-chi phase grain boundaries, it is possible to calculate the free energy of segregation for phosphorus, ΔGP, at an austenite–chi phase boundary:

where \( X_{\text{P}} \) is the concentration of P at the boundary in mols, \( X_{\text{P}}^{\text{B}} \) is the concentration of P in the bulk, \( X_{\text{J}} \) the concentration of an element and the boundary (J = P, Cr, Ni) and \( X_{\text{J}}^{\text{B}} \) the concentration of the element in the bulk. R is the gas constant and T the absolute temperature. Taking the composition at the boundary, and the mean composition from austenite and chi phase as a bulk composition for the ageing conditions present during service, \( \Delta G_{\text{P}} \) = −101.5 kJ/mol. Hence, the segregation of phosphorus at the austenite–chi phase boundary is significantly more favourable during service than segregation to either austenite–austenite or chi phase–chi phase boundaries, correlating with the measured component and distribution of the phosphorus.

The lattice spacings extracted from the FFT for the intragranular precipitates correlate well with γ′ precipitates [12]. Frequently, γ′ precipitates are observed in superalloys such as Inconel alloys, with compositions of (Ni, Co, Fe, Cr)3(Al, Ti) [12, 48]. In Type 316 steels, it has been observed following irradiation and thermal ageing in the temperature range 270–540 °C with a composition of Ni3(Si, Al, Ti, Nb), and a high solubility of the elements Fe, Cr and Mo [48,49,50]. It has been proposed that neutron irradiation has a critical role in γ′ formation, or at least rapidly enhanced the formation kinetics [48]. The γ′ precipitates in current material do not contain Al or Ti. It is suggested that Si can act as an ionic substitute for Ti, in which case it is possible that the low volume of Si in the precipitates fulfils the role of Ti. Given the high quality of atomic resolution images recorded for the γ′ precipitates, it is unlikely that the measured compositions are influenced by the presence of austenite.

The chi phase precipitates were surrounded by a chromium-depleted region, Fig. 12, and this region contained no γ′ precipitates. This depleted austenite region as a minimum contains ~ 6.5 wt% Cr, rising to ~ 10 wt% in the surrounding austenite, Fig. 12. γ′ phase precipitates in regions of austenite where the Cr concentration is greater than 8.3 wt%. Given the partial uncertainty regarding the precipitation sequence, it is not known if γ′ precipitates are taken into solution during the growth of the chi phase or are prevented from forming due to the presence of a chromium-depleted zone. Regardless, it suggests that γ′ is highly sensitive to Cr concentration and only exists due to the abnormally high levels of Cr in these local regions of the overall microstructure.

There has been a significant evolution of the microstructure between the solution-treated pre-service specimen, and the extensively aged post-service specimens. Given that the presence of ferrite precipitates has previously been shown to effect the creep cavitation behaviour of austenitic steels [5], it would be expected that the wide range of precipitates observed in high Cr local regions in the post-service specimen modify the creep behaviour of the material, and this will be considered in a future paper. Certainly a distribution of accelerated cavitation that link to form localised creep-induced cracks has the potential to degrade overall creep life.

Conclusions

An ex-service Type 316H component was observed to have localised regions with different microstructure within the bulk material after prolonged service followed by laboratory exposure at a temperature of ~ 550 °C. These regions contain a greater number of ferrite precipitates and a finer austenite grain structure than the majority of the material. Previous workers have detected a higher concentration of Cr and impurity elements in these regions and have characterised them as heterogeneity arising from the original cast microstructure [5]. The present studies show that these regions have a highly complex microstructure containing G phase, chi phase and γ′ precipitates within the austenite matrix.

-

Faceted G phase precipitates with a composition of (Fe, Ni, Mo)16(Cr)6Si2.3 have been observed at austenite–chi phase boundaries. Phase identification has been achieved using fast Fourier transform-generated diffraction patterns from atomic resolution images of the phase. This G phase has a FCC crystal structure together with a lattice parameter of 1.00 nm. The G phase precipitates have been observed to have a very strong orientation relationship with the neighbouring chi phase, based on observations made during tilt analysis.

-

Chi phase precipitates were observed at austenite–austenite boundaries, showing a faceted morphology and equilibrium P segregation at the austenite–chi phase boundary.

-

Intragranular Fe/Cr-based γ′ precipitates were observed in the austenite, and these have a lower concentration of Si than previous observations.

-

A Cr-depleted region was measured in the austenite matrix surrounding chi phase precipitates, where otherwise ubiquitous γ′ precipitates were absent; either γ′ formation is inhibited or the growing chi phase causes dissolution of γ′ precipitates due to competition for Cr.

References

Rho BS, Hong HU, Nam SW (2000) The effect of δ-ferrite on fatigue cracks in 304L steels. Int J Fatigue 22:683–690

Rho BS, Hong HU, Nam SW (1998) The fatigue crack initiation at the interface between matrix and δ-ferrite in 304L stainless steel. Scr Mater 39:1407–1412

Hong HU, Rho BS, Nam SW (2002) A study on the crack initiation and growth from δ-ferrite/γ phase interface under continuous fatigue and creep-fatigue conditions in type 304L stainless steels. Int J Fatigue 24:1063–1070

Humphries CW, Ridley N (1974) Cavitation in alloy steels during superplastic deformation. J Mater Sci 9:1429–1435. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00552928

Warren AD, Griffiths IJ, Harniman RL, Flewitt PEJ, Scott TB (2015) The role of ferrite in Type 316H austenitic stainless steels on the susceptibility to creep cavitation. Mater Sci Eng A 635:59–69

Hsieh C and Wu W (2012) Overview of intermetallic sigma (σ) phase precipitation in stainless steels. ISRN Metallurgy

Stoter LP (1981) Thermal ageing effects in AISI Type 316 stainless steel. J Mater Sci 16:1039–1051. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00542750

White WE, Le May I (1970) Metallographic observations on the formation and occurrence of ferrite, sigma phase and carbides in austenitic stainless steels part II: studies of AISI type 316 stainless steel. Metallography 3:51–60

Weiss B, Stickler R (1972) Phase instabilities during high temperature exposure of 316 austenitic stainless steel. Metall Trans 3:851–866

Yang Y, Busby JT (2014) Thermodynamic modelling and kinetics simulation of precipitate phases in AISI 316 stainless steels. J Nucl Mater 448:282–293

Morris DG (1978) Creep in Type 316 stainless steel. Acta Metall 26:1143

Padhilha AF, Rios PR (2002) Decomposition of austenite in Austenitic stainless steels. ISIJ Int 42:325–337

Powell DJ, Pilkington R, Miller DA (1988) The precipitation characteristics of 20% Cr/25% Ni–Nb stabilised stainless steel. Acta Metall 36:713–724

Shuroa I, Kuoa HH, Sasakib T, Honob K, Todakaa Y, Umemotoa M (2012) G-phase precipitation in austenitic stainless steel deformed by high pressure torsion. Mater Sci Eng A 552:194–198

Piekarski B (2001) Effect of Nb and Ti additions on microstructure, and identification of precipitates in stabilized Ni–Cr cast austenitic steels. Mater Charact 47:181–186

Ecob RC, Lobb RC, Kohler VL (1987) The formation of G-phase in 20/25 Nb stainless steel AGR fuel cladding alloy and its effect on creep properties. J Mater Sci 22:2867–2880. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01086484

Williams TM, Titchmarsh JM, Arkell DR (1979) A nickel and silicon-rich phase in irradiated FV548 steel. J Nucl Mater 82:199–201

Williams TM, Titchmarsh JM (1981) Silicon-rich phases in austenitic alloys. J Nucl Mater 98:223–226

Vitek JM, David SA, Alexander DJ, Keiser JR, Nanstad RK (1991) Low temperature aging behavior of Type 308 stainless steel weld metal. Acta Metall Mater 39:503–516

Lai JKL (1985) Precipitate phases in Type 321 steel. Mater Sci Technol 1:97–100

Mateo A, Llanes L, Anglada M, Redjaimia A, Metauer G (1997) Characteization of the intermetallic G phase in an AISI 329 duplex stainless steel. J Mater Sci 32:453–454. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018669217124

Vrinat M, Cozar R, Meyzaud Y (1986) Precipitated phases in the ferrite of aged cast duplex stainless steels. Scr Metall 20:1101–1106

Spiegel FX, Bardos D, Beck PA (1963) Ternary G and E silicides and germanides of transition elements. Trans Metall Soc AIME 227:575–579

Sourmail T (2001) Precipitation in creep resistant austenitic steels. Mater Sci Technol 17:1–14

Brown JE, Smith GDW (1991) Atom probe studies of spinodal processes in duplex stainless steels and single- and dual-phase Fe–Cr–Ni alloys. Surf Sci 246:285–291

Escriba DM, Materna-Morris E, Plaut RL, Padhilla AF (2009) Chi-phase precipitation in a duplex steel. Mater Charact 60:1214–1219

Shankar P, Shaikh H, Sivakumar S, Venugopal S, Sundararaman D, Khatak HS (1999) Effect of thermal aging on the room temperature thermal aging properties of AISI type 316LN stainless steel. J Nucl Mater 64:29–34

Stauffer AC, Koss DA, McKirgan JB (2004) Microstructural banding and failure of a stainless steel. Metall Mater Trans A 35:1317–1324

Michalska J, Sozanska M (2006) Qualitative and quantitative analysis of σ and χ phases in 2205 duplex stainless steel. Mater Charact 56:355–362

Ghosh SK, Mondal S (2008) High temperature ageing behaviour of a duplex stainless steel. Mater Charact 59:1776–1783

Gill TPS, Vijayalakshmi M, Gnanamoorthy JB, Padmanabhan KA (1986) Transformation of delta-ferrite during postweld heat treatment of Type 315L stainless steel weld metal. Weld Res 65:122–128

Calliari I, Zanesco M, Ramous E (2006) Influence of isothermal aging on secondary phases precipitation and toughness of a duplex steel SAF 2205. J Mater Sci 41:7643–7649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-006-0857-2

Ruedl E, Sasaki T (1984) Phase instability of thermally aged Cr–Mn austenitic steels. J Nucl Mater 122 & 123:794–798

Senior BA (1990) Effect of phase transformations on the creep rupture properties of two type 316 weld metals. J Mater Sci 25:45–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00544182

Hammar Ö, Svenson U (1979) Influence of steel composition on segregation and microstructure during solidification of austenitic stainless steels. In: Proceedings of the international conference on solidification. The Metals Society, London, pp 401–410

Sorbello F, Hughes GM, Lejcek P, Heard PJ, Flewitt PEJ (2009) Preparation of location specific thin foils from Fe-3% Si bi- and tri-crystals for examination in a FEG-STEM. Ultramicroscopy 109:147–153

Chen B, Flewitt PEJ, Smith DJ, Jones CP (2011) An improved method to identify grain boundary creep cavitation in 316H Austenitic stainless steel. Ultramicroscopy 111:309–313

Faulkner RG, Morgan TS, Little EA (1994) Analytical electron microscopy of thin segregated layers. X-Ray Spectrom 23:195–202

Doig P, Londsdale D, Flewitt PEJ (1981) X-ray microanalysis of grain boundary segregation in steels using the scanning transmission electron microscope. Metall Trans A 12A:1277–1282

Martinez-Ubeda AI (2017) Effect of composition variation and service environment on the long term ageing of Type 316H austenitic stainless steels. PhD Thesis, University of Bristol

Chen B (2011) Effects of thermo-mechanical history on creep damage in 316H austenitic steel. PhD thesis, University of Bristol

Padhilla AF, Escribe DM, Materna-Morris E, Reith M, Klimenkov M (2007) Precipitation in AISI 316L(N) during creep tests at 550 and 600 °C up to 10 years. J Nucl Mater 362:132–138

Keown SR, Thomas RG (1981) Role of delta ferrite in thermal aging of type 316 weld metals. Metal Science 15:386–392

Sevc P, Janovec J, Lejcek P, Zahumensky P, Blach J (2002) Thermodynamics of phosphorus grain boundary segregation in 17Cr12Ni austenitic steel. Scr Mater 46:7–12

Paju M, Grabke HJ (1989) Segregation of phosphorus in austenite in Fe-P and Fe-10Mn-P alloys. Mater Sci Technol 5:148–154

Sevc P, Janovec J, Koutnik M, Vyrostkova A (1995) Equilibrium grain boundary segregation of phosphorus in 2.6Cr–0.7Mo–0.3V steels. Acta Metall Mater 43:251–258

Erhart H, Grabke HJ (1981) Equilibrium segregation of phosphorus at grain boundaries of Fe-P, FE-C-P, Fe-Cr-P and Fe-Cr-C-P alloys. Metal Sci 15:401–408

Brager HR, Garner FA (1978) Swelling as a consequence of gamma prime (γ′) and M23(C, Si)6 formation in neutron irradiated 316 stainless steel. J Nucl Mater 73:9–19

Lee EH, Maziasz PJ, Rowcliffe AF (1981) The structure and composition of phases occurring in austenitic stainless steels in thermal and irradiation environments. In: Holland R, Potter DI, Manusr LK (eds) Phase stability during irradiation. TMS-AIME, Warrendale, pp 191–218

Cawthorne C, Brown C (1977) The occurrence of an ordered FCC phase in neutron irradiated M316 stainless steel. J Nucl Mater 66:201–202

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support by the EPSRC PROMINENT consortium (EP/I003207/1) for the funding for this research and to EDF Energy for provision of the sample materials, compositions and magneprobe measurements. Thanks to the EPSRC JEOL-ARM 200F, EPSRC South of England Analytical Electron Microscope under Grant No. EP/K040375/1. PEJF is grateful to Wolfson College, Oxford for facilitating the collaboration. The full data for the phase identification are available for download from the Research Data Repository of the University of Bristol. https://doi.org/10.5523/bris.3brgj8rdhx552285lcuv189esy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Warren, A.D., Griffiths, I.J. & Flewitt, P.E.J. Precipitation within localised chromium-enriched regions in a Type 316H austenitic stainless steel. J Mater Sci 53, 6183–6197 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-017-1748-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-017-1748-4