Abstract

A novel dot-like Cu2O-loaded TiO2/reduced graphene oxide (rGO) nanoheterojunction was synthesized via UV light reduction for the first time. Cu2O with size of ca. 5 nm was deposited on rGO sheet and TiO2 nanosheets. The products were characterized by infrared spectroscopy, Raman spectrum, UV–Vis diffuse reflectance spectra, XPS techniques, photoluminescence spectra. The results demonstrated that Cu2O and rGO enhanced the absorption for solar light, separation efficiency of electron–hole pairs, charge shuttle and transfer, and eventually improved photoelectrochemical and photocatalytic performance for contaminants degradation. The reaction time and anion precursor could affect the final copper-containing phase. As extending UV irradiation time, Cu2+ was be first reduced to Cu2O and then transformed to metal Cu. In comparison with CH3COO− (copper acetate), NO3 − (copper nitrate) and Cl− (copper chloride), SO4 2− (copper sulfate) was the optimum for synthesizing pure Cu2O phase.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Exploration of an optimum semiconductor nanoheterojunction architecture for enhanced photoelectrochemical properties had been developed with great efforts for years [1,2,3,4,5]. Varied architectures, such as bulk crystal/bulk crystal, core/shell, bulk crystal/dotted crystal et al., had been intensively studied [3, 6, 7]. Architecture of bulk crystal/dotted crystal was similar with a component of dye-sensitized or semiconductor quantum dot-sensitized TiO2 in solar cell, owning high photoelectrochemical performance [8, 9]. For this architecture, dotted crystal with special structure and size had a tunable contact area on the surface of matrix [4, 10, 11]. TiO2 nanosheets exposing (001) facet, which had excellent photocatalytic performance, made itself a stable substrate for building TiO2-based heterojunctions architecture, while its wide band gap of 3–3.2 eV limited the absorption of sun light. Loading dot-like semiconductor with response of visible light on TiO2 nanosheets might be an optimum architecture.

Cuprous oxide (Cu2O) was a relative stable p-type semiconductor with direct band gap of 2.0–2.2 eV which could absorb visible light below 600 nm [12, 13]. In addition, its conduction and valence band positions matched well with those of n-type TiO2, which facilitated separation of photo-induced electron–hole pairs [13,14,15]. However, TiO2 nanosheet/dot-like Cu2O crystal heterojunction still had poor electron conductivity [16]. Reduced graphene oxide (rGO) owning graphitic sp 2 and sp 3-hybrid structures had comparable conductivity of metal and large surface area as a substrate for building heterojunctions [17, 18]. It is reported that particles of TiO2 or Cu2O combining with rGO had enhanced charge shuttle and transfer performance [13, 19, 20]. So the dot-like Cu2O-loaded TiO2/rGO nanoheterojunction might become one of the most efficient TiO2-based photocatalysts.

General method for loading dot-like Cu2O crystal on the TiO2 or rGO is reduction of various cupric salts with strong chemical reagents in alkaline condition at high temperature [14, 21, 22]. For example, Wang or Geng et al. [14, 23] synthesized nanocrystalline Cu2O on TiO2 frame or arrays using cupric acetate as precursor and glucose as reducing reagent. Gao et al. [24] loaded Cu2O particle on rGO sheet using l-ascorbic acid as reductive reagent in mild condition. Compared to chemical liquid reduction, photochemical synthesis of Cu2O had advantages of free chemical reagents addition, room temperature, atmospheric pressure, free of pH adjustment via alkali or acid. In previous reports, Cu2O was synthesized via γ-ray radiation [25, 26]. However, γ-ray radiated by 60Co source is very environmental unfriendly, harmful and strictly restricted by laws.

In this work, γ-ray was alternated by a ultraviolent (UV) light (main peak 254 nm, 25 W), and dot-like Cu2O crystal with size of ca. 5 nm was successfully deposited on TiO2 nanosheet/rGO. To our knowledge, this has never been reported before. The results revealed that the newly designed nanoheterojunction had strong absorption of solar light, high separation efficiency of electron–hole pairs and high performance of charge shuttle and transfer. Surfactants such as sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate (SDBS) existing in cleaning agents, dyes such as methyl orange (MO), rhodamine B (RhB) as the aromatic-containing macromolecules existing in waste water were selected to evaluate its photocatalytic activity [27].

More importantly, various cupric salts with different anions such as SO4 2−, Cl−, CH3COO−, NO3 − were employed to synthesize Cu2O in previous works [14, 28,29,30]. In this report, taken different stabilities, chemical activities and chelating ability with positive ion into consideration, these cupric salts as precursors were studied to explore the synthetic mechanism under photochemical condition.

Experiment

Materials

Natural graphite was purchased from Qingdao Baichun graphitic Co., Ltd. Fluorine tin oxide (FTO)-coated glass (resistivity <10 Ω sq−1) was purchased from Zhuhai Kaivo Electronic Components Co., Ltd. The other chemical reagents were purchased from Sinopharm chemical reagent Co., Ltd. And all the chemicals were used without further purification.

Synthesis of graphite oxide

Graphite oxide was synthesized by the typical modified Hummers’ method [31]. In details, 2 g of natural graphite flakes was mixed with 1 g sodium nitrate in the ice bath. Then, 50 mL concentrated H2SO4 was slowly added into the mixture under stirring to keep temperature under 5 °C. 0.3 g potassium permanganate was slowly put into the mixture under stirring to maintain temperature below 20 °C. Then, 7 g potassium permanganate was slowly added into the mixture for 1 h to keep temperature below 20 °C. Successively, the mixed solution was stirred at 35 °C for 2 h, followed by slow addition of deionized (DI) water (90 mL). After that, the solution was heated to 98 °C and kept for 15 min. The suspension was further diluted with 55 mL DI warm water, and then, 7 mL H2O2 was added to terminate the reaction. The mixture was filtered and washed with 10% HCl (1 L) and DI water (1 L) until pH 7. The graphite oxide product was vacuum-dried at 40 °C for 12 h.

Synthesis of TiO2 nanosheets

The TiO2 nanosheets were synthesized by hydrothermal method [32]. In a typical experimental procedure, 5 mL of tetrabutyl titanate [Ti(OBu)4, ≥98%] and 0.6 mL of hydrofluoric acid (HF) (≥40%) were mixed in a dried Teflon autoclave with a capacity of 20 mL, and kept at 180 °C for 24 h. The powder was separated by centrifugation, washed by water and ethanol several times, consecutively. The final product was vacuum-dried at 80 °C for 6 h. Caution! HF is extremely corrosive and a contact poison, and it should be handled with extreme care. Hydrofluoric acid solution should be stored in plastic container and used in a fume hood.

Synthesis of TiO2/Cu2O composite

20 mg TiO2 nanosheets were sonicated in 100 mL ethanol for 15 min and then poured into 100 ml CuSO4 aqueous solution (containing 3 mmol CuSO4·5H2O) with fiercely stirring. The following procedure was the same with the Cu2O synthesis (shown in supporting information), and this obtained TiO2/Cu2O composite was labeled as TC.

Synthesis of TiO2/rGO/Cu2O composites

10 mg graphite oxide was sonicated in 100 mL deionized water at 30–40 °C for 30 min to obtain clear suspension; then, 3 mmol CuSO4·5H2O was added and dissolved. The following synthesis procedure was as same as that of TC and labeled as TGC (6 h UV light irradiation).

Other samples with irradiation of 2, 4, 12 h (donated as TGC-2, TGC-4, TGC-12 h) are also prepared.

Several other cupric salts [such as CuCl2, Cu(CH3COO)2, Cu(NO3)2] were employed to substitute CuSO4 to obtain final products labeled as TGC-Cl2, TGC-A, TGC-N (6 h UV light irradiation).

Photoelectrochemical performance

The photoelectrochemical measurement was performed by a CHI 760E electrochemical workstation (Shanghai CH instrument Co., Ltd, China), with Pt plate as counter electrode, Ag/AgCl (filled with 3.5 M KCl aqueous solution) as reference electrode and 0.2 M Na2SO4 aqueous solution as electrolyte. The working electrode was prepared as follows: 10 mg product powder was mixed with 22 μL PVDF poly(vinylidene fluoride) solution, and that PVDF was dissolved in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (wt% 5%) with weight ratio of 90:10 to make slurry. The film was made by doctor blade method on FTO for area of 1×1 cm2, then vacuum-dried at 100 °C for 12 h. The uncovered area of FTO which would be immersed in electrolyte was protected by insulting glue.

Photocatalytic performance

The photocatalytic performance was measured by photodegradation of MO, RhB and SDBS. In a typical process, 20 mg of photocatalysts and 100 mL MO/SDBS/RhB solution (20 mg L−1) were sonicated for 10 min to obtain homogeneous suspension. Before light irradiation, the suspension was stirred for 0.5 h in dark to achieve adsorption and desorption equilibrium. Then, 5 mL of the solution was extracted every 0.5 h for UV–Vis absorption measurement. The photoreaction was carried out in the protection of cycling cool water. The light source is 350 W Xenon lamp to simulate solar light (range of spectrum is from 200 to 2500 nm).

Characterization

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) was performed on DX-2700 X-ray diffractometer (Dandong Fangyuan, China) with monochromatized Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) at 40 kV and 30 mA. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were taken with JEOL JEM-2100 transmission electron microscope at 200 kV. The concentration of MO was analyzed by measuring the light absorption at 484 nm UV–Vis 756PC Spectrophotometer (Shanghai Spectrum Instruments Co., Ltd. China). Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were obtained using BRUKER Tensor II spectrometer in the frequency range of 4000–400 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1. Measurement of Raman spectra was performed on a Raman DXR Microscope (Thermo Fisher, USA) with excitation laser beam wavelength of 532 nm. PL spectrum was measured at room temperature on a 7-PLSpec fluorescence spectrophotometer (Saifan, China). The wavelength of the excitation light is 325 nm. Optical absorption spectra were recorded on a UV–Vis spectrometer (UV-2600, Shimadzu, Japan) over a spectral range of 200–1400 nm. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo ESCALAB 250XI) with Al Kα (hv = 1486.6 eV) radiation and beam spot of 500 μm was operated at 150 W. The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface areas were characterized by a surface area analyzer (Micromeritics, ASAP2020 M, USA) with nitrogen adsorption at 77 K.

Results and discussion

Characterization of phase and morphology

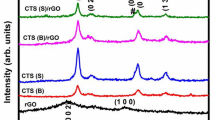

The XRD peaks of crystalline Cu2O were observed in Fig. S2a and 1 for TC and TGC, which indicated Cu2O (PDF#05-0667) could be synthesized under UV radiation directly without assistance of any chemical reagent at room temperature. Peaks of crystallized anatase TiO2 (PDF#21-1272) were observed in the TC and TGC samples. Graphene oxide (GO) fabricated by Hummers’ method in aqueous solution was reduced to rGO under the UV irradiation [31, 33, 34], which was also demonstrated by IR spectrum shown in Fig. 3a. However, no GO or rGO peak was found since ordered stacking of rGO sheets had been disrupted by loading TiO2 nanosheets and Cu2O [33].

TiO2 nanosheets were prepared by the classical hydrothermal method [32], which had rectangular shape with the length of ca. 50 nm and thickness of 5 nm, as shown in Fig. S1. As Cu2O composited with TiO2 forming sample TC, large amounts of Cu2O nanocrystals were deposited on TiO2 nanosheets and even self-aggregated because of large quantities, as shown in Fig. 2a. After further compositing with rGO, it is observed that large amounts of Cu2O nanocrystal with size of ca. 5 nm adhered on TiO2 nanosheets and rGO sheet in Fig. 2b, c, which was ascribed to residual oxygen-containing groups of rGO facilitating dispersion of Cu+. This new morphology was achieved only via UV irradiation without addition of any chemical reducing reagent, so this work provides a novel way for synthesizing nano-Cu2O and its composites.

Characterization of IR and Raman spectrum

Chemical bond and phases of composites were characterized by FRIT and Raman spectrum (Fig. 3). In Fig. 3a, around 3420 cm−1 corresponded to the O–H stretching vibration of alcoholic or phenolic groups as well as intercalated or adsorbed water molecular for all samples [35,36,37,38]. The peak of 1631 cm−1 was attributed to bending mode of surface –OH or water for TiO2, TC [39]. The broadband around 560 cm−1 between 880 and 400 cm−1 showed the vibration of Ti–O–Ti bonds of sample TiO2, TC, TGC [40]. The sharp peak of 623 cm−1 was attributed to the stretching of copper(I)–O bond in TC and TGC, which indicated the formation of Cu2O [41]. In comparison with stretching modes of carbonyl (C=O) bond (1724 cm−1), conjugation absorption for bending mode of water and C=C sp 2 hybrid(1622 cm−1), tertiary alcohol (C–OH) bending (1375) and alkoxy (C–O) vibrations (1060) in IR spectrum of GO, most oxygen-containing groups of rGO in TGC were removed by the UV reduction [42, 43], its absorption peak of C=C bond was shifted to 1578 cm−1. The 1240 cm−1 peak should be attributed to stretching modes of the epoxy (C–O–C) group that can hardly removed by UV irradiation [44].

In Fig. 3b, four strong vibration peaks at 143 cm−1 (Eg), 393 cm−1 (B1g), 512 cm−1 (A1g) and 615 cm−1 (E1g) were ascribed to the five Raman active modes (A1g + B1g + 3Eg) of anatase [45]. The peaks around 120–180 cm−1 for TC and TGC were decomposed to the sharp peak at 152.6 cm−1, which should be mainly attributed to the Γ (1)15 (LO) infrared (ir)-allowed mode in perfect Cu2O crystals and a small peak for Eg mode of anatase as shown in Fig. 3c [46]. The peak at 505 and 621 cm−1 should be assigned to the overlapping of Raman vibration mode of crystalline Cu2O and TiO2 [45, 47]. The peak at 394 cm−1 was the B1g mode of anatase TiO2 for TC and TGC. Phase determination of Raman spectra agreed with the results of XRD (Fig. 1). D band provided information about defect of graphitic structure and the presence of sp 3-hybridized domain [17]. G band was a prominent feature of the pristine graphite, corresponding to the first-order scattering of the E2g mode [48]. In Fig. 3d, the position of D and G band of GO was about 1357 and 1586 cm−1, respectively. After reduction, the D and G band for rGO of TGC shifted to 1350, 1592 cm−1, respectively, and I D/I G increased from 0.91 to 1.13 after UV reduction of GO, which indicated a decrease in average size and increase in numbers of the sp 2-hybridized domains of rGO in TGC, comparing with that of GO [48, 49].

XPS analysis

Figure 4a demonstrates the full spectrum of sample TGC, while Fig. 4b–d focuses on the specific binding energy of element Ti, Cu and C, respectively. The Ti 2p peaks located at the binding energies of 459.0 and 464.8 eV were attributed to Ti 2p 3/2 and Ti 2p 1/2, which corresponded to Ti4+ [50]. In Fig. 4c, the peak for Cu 2p 3/2 was decomposed into two peaks, the main peak of which at 932.6 eV was the characteristic of Cu+ in Cu2O [28], and the peak at 934.1 eV indicated the existence of Cu2+ in CuO [51]. XPS could only detect the shallow surface elements composition, so the observation of Cu2+ indicated the oxidation of a small portion of Cu2O during sample drying and handing under normal ambient condition. This phenomenon had been reported by many researchers on the synthesis of Cu2O nanoparticles. From C 1s XPS spectrum of GO (Fig. 4d), the peaks at 282.8, 286.7, 288.5 eV were assigned to the sp 2-hybrid bond (C–C, C=C, C–H), C–O and O–C=O bond, respectively [52]. After UV reduction, a large amount of C–O and O–C=C bonds were removed as indicated by the decrease in intensities of these two peaks, which was consistent with results of IR spectra.

Selective adsorption and photocatalytic performance

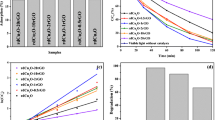

Photocatalytic performances of samples were characterized by degradation of MO, SDBS and RhB (Fig. 5a–c). All experiments were carried out in nearly neutral solution, shown in Table S1. The MO is no self-degradation. Pure TiO2 nanosheets had the lowest degradation ability for 26.7%, while sample TC had stronger degradation ability (50.9%) after compositing with Cu2O. Further incorporation of rGO can facilitate MO adsorption, and thus, the TGC had highest photocatalytic activity for MO degradation (70.6%). For SDBS degradation, TiO2 had lowest photocatalytic activity (20.8%). Sample TGC had slightly better activity than TC (ca. 70%). For RhB degradation, TiO2 still had poorest activity than others because of its absorbance limitation of solar light. TC had better photocatalytic performance than TGC. As shown in Fig. 5d, within 2.5 h, MO and SDBS could be decomposed dramatically by TC and TGC under solar light; however, the degradation efficiency for RhB was much lower than that for other contaminations, which indicated that only some special contaminations could be decomposed by nanoheterojunction effectively.

The adsorption of photocatalysts for contaminations played an important role in the process of photocatalytic reactions. Contaminants owning opposite charge with the photocatalysts could easily adsorb on the surface of photocatalysts preferentially. However, given that the charge of MO/SDBS/RhB (molecule structures are shown in Fig. 5e) in aqueous solution and adsorption abilities of the synthesized photocatalysts, the reverse charge principle was not perfect for explaining adsorption difference. Taken some special groups of contaminants into consideration, nitrogen-containing groups may also affect the eventual adsorption outcome.

Chemical stability of Cu2O particles is one of predominant factors for photochemical applications. Exposed to UV light (irradiated by varied lamp), Cu2O can be reduced to metal Cu [53, 54]. However, in this work under standard simulated solar light, Cu2O was very stable and no metal copper was found even after 12 h with the characterization of X-ray diffraction (Fig. 5f).

Photocatalytic mechanism

As shown in Fig. 6a, TiO2 could only absorb UV light below 387 nm. Cu2O enhanced absorption of visible light below 640 nm in TC. Moreover, with incorporation of rGO, TGC had highest light absorbance, so it induced more photo-induced charge carriers and higher degradation rate. Optical band gap of composite was calculated using Tauc plot shown in Fig. S3d [55]. Comparing with pure TiO2 (3.2 eV), optical band gap of TC and TGC decreased to 2.72 and 2.64 eV, respectively.

PL spectrum was employed to characterize separation efficiency of photo-generated electron–hole pairs. As shown in Fig. 6b, several peaks such as 400, 434, 470, 544 nm were observed in PL spectrum of TiO2, which attributed to electron transition from the conduction band to valence band, band-edge free excitons, oxygen vacancies or surface defect [56, 57]. TC had lower intensity of PL than pure TiO2 that inferred Cu2O could accept the photocharge from TiO2. Furthermore, lowest intensity of TGC demonstrated that rGO could further accept the photo-induced electron and enhance separation efficiency of electron–hole pairs.

TiO2 electrode in Na2SO4 aqueous solution had a positive photocurrent, indicating its n-type semiconductor nature, shown in inset of Fig. 6c. Oppositely, sample TC and TGC exhibited a negative current response and larger photocurrent, which was a sign of p-type semiconductor of Cu2O (also demonstrated in Fig. S2b). In addition, Cu2O could also enhance the charge transportation in TC, compared to the current baseline of TiO2. The rGO further enhanced the conductivity of TGC. As shown in Fig. 6d, the typical electrochemical impedance spectra were presented as Nyquist plots. For fitting the EIS, equivalent circuit [model: R(Q(RW))(Q(RW))] was demonstrated that the simulating results fitted the experimental very well. Q is constant phase element (CPE). R b represented the bulk resistance, CPEs should be considered in the nonhomogeneous condition of the composites, associating with the capacitor, and R s are the resistance of the solid-state interface layer which is formed at the highly charged state due to the passivation reaction between the electrolyte and the surface of the electrode, corresponding to the first semicircle at high frequency [58]. CPEdl and R ct are the double-layer capacitance and the charge-transfer resistance, corresponding to the second semicircle at medium frequency. Nyquist plots of EIS showed that nanocrystalline Cu2O could decrease the R ct from 9.4×105 to 1.2×104 ohm cm2 for TC because of the smaller semicircle at the medium frequency, in comparison with TiO2 (Fig. 6d) [40]. The resistance of TGC dramatically decreased to 4.4 ohm cm2 because of high conductivity of rGO as shown in inset of Fig. 6d. Its high charge shuttle and transfer enhanced the degradation ability.

Photocatalytic performance of TGC was the best in the photocatalysts for MO and SDBS degradation. The schematic illustration is shown in Fig. 7: (1) The band gap of Cu2O determined by UV–Vis diffuse reflection spectroscopy (Fig. S3b) is 1.75 eV, which could enhance visible light absorption below 708 nm, generating more electron–hole pairs; (2) the matching energy band structure facilitated the separation of electron–hole pairs of heterojunction [15, 29, 62]; (3) rGO facilitated the dispersion of nanocrystals, transfer and shuttle of photo-generated electron in metal oxide particles [63].

Illustration of transfer of photo-generated electron–hole pairs excited by solar light. The dissolved O2 scavenge the photo-generated electron transferred from Cu2O or TiO2 to form O2 −, the photohole oxidized H2O to OH or decompose dye directly. Band gaps of TiO2 and Cu2O were determined by UV–Vis diffuse reflection spectroscopy. Energy levels referred to Refs. 22, 59,60,61

Reduction mechanism of TGC via UV

Figure 8a shows the effect of irradiation time on phase of products. No Cu2O could be detected by the XRD after 2-h reaction. If the reaction prolonged for 4 h, a weak peak (111) of Cu2O could be observed, then more Cu2O were synthesized after 6 h. However, when the UV reduction time extended to 12 h, part of Cu2O particle converted to metal Cu.

Several other cupric salts [such as CuCl2, Cu(CH3COO)2, Cu(NO3)2] were tried to synthesize Cu2O products, labeled as TGC-Cl2, TGC-A, TGC-N (other synthesizing conditions were the same as that of sample TGC). There was CH3COOCu (PDF#28-0392) formed under UV reduction with (CH3COO)− involvement, shown in Fig. 8b. As NO3 − used, the final phases of TGC-N could not be identified at present. As Cl− used, all XRD peaks for TGC-Cl2 were assigned to anatase and no copper-containing phase was detected. Furthermore, if NaCl was added to the TGC synthesis process, no diffraction peaks of copper-containing phase were found either (shown in Fig. 8b donated as TGC-Cl). It demonstrated that Cl− could chelate Cu+ preferentially instead of OH−.

Above all, the mechanism of synthesizing Cu2O could be proposed as follows:

If extending irradiation time, there would be:

If CH3COO− was employed as the precursor:

If Cl− was added into the reaction system of TGC, the reaction was changed to:

So compared to CH3COO−/NO3 −/Cl−, SO4 2− is the optimum anion for UV reduction synthesis of Cu2O.

Conclusion

Pure Cu2O, TiO2/Cu2O, TiO2/rGO/Cu2O nanoheterojunctions were fabricated by novel UV reduction method, and large amounts of dot-like Cu2O nanocrystals with size of ca. 5 nm were formed on the rGO or TiO2 nanosheets. Sample TGC achieved the strongest absorption for solar light, highest separation efficiency of photo-induced electron–hole pairs. It had p-type photocurrent response under solar light and excellent photocatalytic performance. The adsorption abilities for catalysts varied with different dyes or surfactant, determined by nitrogen-containing groups and surface charge. Extending irradiation time could convert Cu2O to metal copper. In comparison with CH3COO−/NO3 −/Cl−, SO4 2− is the optimum anion for synthesis of pure Cu2O phase under UV condition.

References

Wang H, Zhang L, Chen Z, Hu J, Li S, Wang Z, Liu J, Wang X (2014) Semiconductor heterojunction photocatalysts: design, construction, and photocatalytic performances. Chem Soc Rev 43(15):5234–5244. doi:10.1039/c4cs00126e

Bessegato G, Guaraldo T, de Brito J, Brugnera M, Zanoni M (2015) Achievements and trends in photoelectrocatalysis: from environmental to energy applications. Electrocatalysis 6(5):415–441. doi:10.1007/s12678-015-0259-9

Rajeshwar K, de Tacconi NR, Chenthamarakshan CR (2001) Semiconductor-based composite materials: preparation, properties, and performance. Chem Mater 13(9):2765–2782. doi:10.1021/cm010254z

Chen H, Li W, Liu H, Zhu L (2011) Performance enhancement of CdS-sensitized TiO2 mesoporous electrode with two different sizes of CdS nanoparticles. Microporous Mesoporous Mater 138(1–3):235–238. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2010.09.021

Yu L, Zhang Y, Zhi Q, Wang Q, Gittleson FS, Li J, Taylor AD (2015) Enhanced photoelectrochemical and sensing performance of novel TiO2 arrays to H2O2. Sens Actuator B: Chem 211:111–115. doi:10.1016/j.snb.2015.01.060

Tamiolakis I, Lykakis IN, Armatas GS (2015) Mesoporous CdS-sensitized TiO2 nanoparticle assemblies with enhanced photocatalytic properties: selective aerobic oxidation of benzyl alcohols. Catal Today 250:180–186. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2014.03.047

Banin U, Ben-Shahar Y, Vinokurov K (2014) Hybrid semiconductor-metal nanoparticles: from architecture to function. Chem Mater 26(1):97–110. doi:10.1021/cm402131n

Chen H, Fu W, Yang H, Sun P, Zhang Y, Wang L, Zhao W, Zhou X, Zhao H, Jing Q, Qi X, Li Y (2010) Photosensitization of TiO2 nanorods with CdS quantum dots for photovoltaic devices. Electrochim Acta 56(2):919–924. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2010.10.003

O’Regan B, Gratzel M (1991) A low-cost, high-efficiency solar cell based on dye-sensitized colloidal TiO2 films. Nature 353(6346):737–740

Lin Z-Q, Lai Y-K, Hu R-G, Li J, Du R-G, Lin C-J (2010) A highly efficient ZnS/CdS@TiO2 photoelectrode for photogenerated cathodic protection of metals. Electrochim Acta 55(28):8717–8723. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2010.08.017

Wang C, Jiang Z, Wei L, Chen Y, Jiao J, Eastman M, Liu H (2012) Photosensitization of TiO2 nanorods with CdS quantum dots for photovoltaic applications: a wet-chemical approach. Nano Energy 1(3):440–447. doi:10.1016/j.nanoen.2012.02.005

Hara M, Kondo T, Komoda M, Ikeda S, Kondo JN, Domen K, Shinohara K, Tanaka A (1998) Cu2O as a photocatalyst for overall water splitting under visible light irradiation. Chem Commun 3:357–358. doi:10.1039/a707440i

Tran PD, Wong LH, Barber J, Loo JSC (2012) Recent advances in hybrid photocatalysts for solar fuel production. Energy Environ Sci 5(3):5902–5918. doi:10.1039/c2ee02849b

Wang M, Sun L, Lin Z, Cai J, Xie K, Lin C (2013) p-n heterojunction photoelectrodes composed of Cu2O-loaded TiO2 nanotube arrays with enhanced photoelectrochemical and photoelectrocatalytic activities. Energy Environ Sci 6(4):1211–1220. doi:10.1039/c3ee24162a

Ola O, Maroto-Valer MM (2015) Review of material design and reactor engineering on TiO2 photocatalysis for CO2 reduction. J Photochem Photobiol C 24:16–42. doi:10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2015.06.001

Pelaez M, Nolan NT, Pillai SC, Seery MK, Falaras P, Kontos AG, Dunlop PSM, Hamilton JWJ, Byrne JA, O’Shea K, Entezari MH, Dionysiou DD (2012) A review on the visible light active titanium dioxide photocatalysts for environmental applications. Appl Catal B 125:331–349. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2012.05.036

Pei S, Cheng H-M (2012) The reduction of graphene oxide. Carbon 50(9):3210–3228. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2011.11.010

Fernández-Merino MJ, Guardia L, Paredes JI, Villar-Rodil S, Solís-Fernández P, Martínez-Alonso A, Tascón JMD (2010) Vitamin C is an ideal substitute for hydrazine in the reduction of graphene oxide suspensions. J Phys Chem C 114(14):6426–6432. doi:10.1021/jp100603h

Bell NJ, Ng YH, Du A, Coster H, Smith SC, Amal R (2011) Understanding the enhancement in photoelectrochemical properties of photocatalytically prepared TiO2-reduced graphene oxide composite. J Phys Chem C 115(13):6004–6009. doi:10.1021/jp1113575

Yu L, Dong K, Zhang Y, Wang Q, Zhi Q (2014) Tuned n/n or n/p heterojunctions for reduced graphene oxide and titania nanosheets and their electrochemical properties. Mater Chem Phys 148(3):803–809. doi:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2014.08.052

Talebian A, Entezari MH, Ghows N (2013) Complete mineralization of surfactant from aqueous solution by a novel sono-synthesized nanocomposite (TiO2–Cu2O) under sunlight irradiation. Chem Eng J 229:304–312. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2013.05.117

Zhang S, Peng B, Yang S, Fang Y, Peng F (2013) The influence of the electrodeposition potential on the morphology of Cu2O/TiO2 nanotube arrays and their visible-light-driven photocatalytic activity for hydrogen evolution. Int J Hydrogen Energy 38(32):13866–13871. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2013.08.081

Geng Z, Zhang Y, Yuan X, Huo M, Zhao Y, Lu Y, Qiu Y (2015) Incorporation of Cu2O nanocrystals into TiO2 photonic crystal for enhanced UV–Visible light driven photocatalysis. J Alloy Compd 644:734–741. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.05.075

Gao Z, Liu J, Xu F, Wu D, Wu Z, Jiang K (2012) One-pot synthesis of graphene–cuprous oxide composite with enhanced photocatalytic activity. Solid State Sci 14(2):276–280. doi:10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2011.11.032

Miao W, Liu H, Zhang Z, Chen J (2008) Large-scale growth and shape evolution of micrometer-sized Cu2O cubes with concave planes via γ-irradiation. Solid State Sci 10(10):1322–1326. doi:10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2008.01.015

Liu H, Miao W, Yang S, Zhang Z, Chen J (2009) Controlled synthesis of different shapes of Cu2O via γ-irradiation. Cryst Growth Des 9(4):1733–1740. doi:10.1021/cg800703n

Fujishima A, Zhang X, Tryk DA (2008) TiO2 photocatalysis and related surface phenomena. Surf Sci Rep 63(12):515–582. doi:10.1016/j.surfrep.2008.10.001

Liu L, Yang W, Li Q, Gao S, Shang JK (2014) Synthesis of Cu2O nanospheres decorated with TiO2 nanoislands, their enhanced photoactivity and stability under visible light illumination, and their post-illumination catalytic memory. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 6(8):5629–5639. doi:10.1021/am500131b

Praveen Kumar D, Lakshmana Reddy N, Mamatha Kumari M, Srinivas B, Durga Kumari V, Sreedhar B, Roddatis V, Bondarchuk O, Karthik M, Neppolian B, Shankar MV (2015) Cu2O-sensitized TiO2 nanorods with nanocavities for highly efficient photocatalytic hydrogen production under solar irradiation. Sol Energy Mater Sol Cells 136:157–166. doi:10.1016/j.solmat.2015.01.009

Zhang J, Liu W, Wang X, Wang X, Hu B, Liu H (2013) Enhanced decoloration activity by Cu2O@TiO2 nanobelts heterostructures via a strong adsorption-weak photodegradation process. Appl Surf Sci 282:84–91. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2013.05.054

Hummers WS, Offeman RE (1958) Preparation of graphitic oxide. J Am Chem Soc 80(6):1339. doi:10.1021/ja01539a017

Han X, Kuang Q, Jin M, Xie Z, Zheng L (2009) Synthesis of titania nanosheets with a high percentage of exposed (001) facets and related photocatalytic properties. J Am Chem Soc 131(9):3152–3153. doi:10.1021/ja8092373

Tu Y, Ichii T, Utsunomiya T, Sugimura H (2015) Vacuum-ultraviolet photoreduction of graphene oxide: electrical conductivity of entirely reduced single sheets and reduced micro line patterns. Appl Phys Lett 106(13):133105. doi:10.1063/1.4916813

Zhang Y-L, Guo L, Xia H, Chen Q-D, Feng J, Sun H-B (2014) Photoreduction of graphene oxides: methods, properties, and applications. Adv Opt Mater 2(1):10–28. doi:10.1002/adom.201300317

Dong K, Yu L, Zhang Y, Wang Q, Neppolian B (2014) Green synthesis of sulfur/graphene nanocomposite and photocatalytic performance. Sci Adv Mater 6(8):1828–1835. doi:10.1166/sam.2014.1948

Mathkar A, Tozier D, Cox P, Ong P, Galande C, Balakrishnan K, Leela Mohana Reddy A, Ajayan PM (2012) Controlled, stepwise reduction and band gap manipulation of graphene oxide. J Phys Chem Lett 3(8):986–991. doi:10.1021/jz300096t

Nethravathi C, Rajamathi M (2008) Chemically modified graphene sheets produced by the solvothermal reduction of colloidal dispersions of graphite oxide. Carbon 46(14):1994–1998. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2008.08.013

Kim UJ, Furtado CA, Liu X, Chen G, Eklund PC (2005) Raman and IR Spectroscopy of chemically processed single-walled carbon nanotubes. J Am Chem Soc 127(44):15437–15445. doi:10.1021/ja052951o

Li G, Li L, Boerio-Goates J, Woodfield BF (2005) High purity anatase TiO2 nanocrystals: near room-temperature synthesis, grain growth kinetics, and surface hydration chemistry. J Am Chem Soc 127(24):8659–8666. doi:10.1021/ja050517g

Zhang H, Lv X, Li Y, Wang Y, Li J (2010) P25-graphene composite as a high performance photocatalyst. ACS Nano 4(1):380–386. doi:10.1021/nn901221k

Hou C, Quan H, Duan Y, Zhang Q, Wang H, Li Y (2013) Facile synthesis of water-dispersible Cu2O nanocrystal-reduced graphene oxide hybrid as a promising cancer therapeutic agent. Nanoscale 5(3):1227–1232. doi:10.1039/c2nr32938g

Collins WR, Schmois E, Swager TM (2011) Graphene oxide as an electrophile for carbon nucleophiles. Chem Commun 47(31):8790–8792. doi:10.1039/c1cc12829a

Colthup N (2012) Introduction to infrared and Raman spectroscopy. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Si Y, Samulski ET (2008) Synthesis of water soluble graphene. Nano Lett 8(6):1679–1682. doi:10.1021/nl080604h

Wang Y, Y-n Zhang, Zhao G, Tian H, Shi H, Zhou T (2012) Design of a novel Cu2O/TiO2/carbon aerogel electrode and its efficient electrosorption-assisted visible light photocatalytic degradation of 2,4,6-Trichlorophenol. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 4(8):3965–3972. doi:10.1021/am300795w

Powell D, Compaan A, Macdonald JR, Forman RA (1975) Raman-scattering study of ion-implantation-produced damage in Cu2O. Phys Rev B 12(1):20–25

Wu L, L-k Tsui, Swami N, Zangari G (2010) Photoelectrochemical stability of electrodeposited Cu2O films. J Phys Chem C 114(26):11551–11556. doi:10.1021/jp103437y

Tuinstra F, Koenig JL (1970) Raman spectrum of graphite. J Chem Phys 53(3):1126–1130. doi:10.1063/1.1674108

Stankovich S, Dikin DA, Piner RD, Kohlhaas KA, Kleinhammes A, Jia Y, Wu Y, Nguyen ST, Ruoff RS (2007) Synthesis of graphene-based nanosheets via chemical reduction of exfoliated graphite oxide. Carbon 45(7):1558–1565. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2007.02.034

Fang WQ, Zhou JZ, Liu J, Chen ZG, Yang C, Sun CH, Qian GR, Zou J, Qiao SZ, Yang HG (2011) Hierarchical structures of single-crystalline anatase TiO2 nanosheets dominated by 001 facets. Chem A Eur J 17(5):1423–1427. doi:10.1002/chem.201002582

Yin M, Wu C-K, Lou Y, Burda C, Koberstein JT, Zhu Y, O’Brien S (2005) Copper oxide nanocrystals. J Am Chem Soc 127(26):9506–9511. doi:10.1021/ja050006u

Wang W-S, Wang D-H, Qu W-G, Lu L-Q, Xu A-W (2012) Large ultrathin anatase TiO2 nanosheets with exposed 001 facets on graphene for enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity. J Phys Chem C 116(37):19893–19901. doi:10.1021/jp306498b

Lalitha K, Sadanandam G, Kumari VD, Subrahmanyam M, Sreedhar B, Hebalkar NY (2010) Highly stabilized and finely dispersed Cu2O/TiO2: a promising visible sensitive photocatalyst for continuous production of hydrogen from glycerol: water mixtures. J Phys Chem C 114(50):22181–22189. doi:10.1021/jp107405u

Xu S, Sun DD (2009) Significant improvement of photocatalytic hydrogen generation rate over TiO2 with deposited CuO. Int J Hydrogen Energy 34(15):6096–6104. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2009.05.119

Li Y, Wang B, Liu S, Duan X, Hu Z (2015) Synthesis and characterization of Cu2O/TiO2 photocatalysts for H2 evolution from aqueous solution with different scavengers. Appl Surf Sci 324:736–744. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.11.027

Liu B, Wang X, Cai G, Wen L, Song Y, Zhao X (2009) Low temperature fabrication of V-doped TiO2 nanoparticles, structure and photocatalytic studies. J Hazard Mater 169(1–3):1112–1118. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.04.068

Liqiang J, Honggang F, Baiqi W, Dejun W, Baifu X, Shudan L, Jiazhong S (2006) Effects of Sn dopant on the photoinduced charge property and photocatalytic activity of TiO2 nanoparticles. Appl Catal B 62(3–4):282–291. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2005.08.012

He B-L, Dong B, Li H-L (2007) Preparation and electrochemical properties of Ag-modified TiO2 nanotube anode material for lithium–ion battery. Electrochem Commun 9(3):425–430. doi:10.1016/j.elecom.2006.10.008

Jung HS, Park N-G (2015) Perovskite solar cells: from materials to devices. Small 11(1):10–25. doi:10.1002/smll.201402767

Huang L, Peng F, Ohuchi FS (2009) “In situ” XPS study of band structures at Cu2O/TiO2 heterojunctions interface. Surf Sci 603(17):2825–2834. doi:10.1016/j.susc.2009.07.030

Giovannetti G, Khomyakov PA, Brocks G, Karpan VM, van den Brink J, Kelly PJ (2008) Doping graphene with metal contacts. Phys Rev Lett 101(2):026803

Liu L, Gu X, Sun C, Li H, Deng Y, Gao F, Dong L (2012) In situ loading of ultra-small Cu2O particles on TiO2 nanosheets to enhance the visible-light photoactivity. Nanoscale 4(20):6351–6359. doi:10.1039/c2nr31859h

Wang X, Zhi L, Müllen K (2008) Transparent, conductive graphene electrodes for dye-sensitized solar cells. Nano Lett 8(1):323–327. doi:10.1021/nl072838r

Acknowledgements

The financial support for this study by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21476262), the Technology Development Plan of Qingdao (No. 14-2-4-108-jch) and Research Funds for the Central Universities (15CX05032A, 15CX05056A) is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, K., He, J., Liu, J. et al. Photocatalytic performance of Cu2O-loaded TiO2/rGO nanoheterojunctions obtained by UV reduction. J Mater Sci 52, 6754–6766 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-017-0911-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-017-0911-2