Abstract

The article presents a new thermo-mechanical machining method for the manufacture of long low-rigidity shafts which combines straightening and heat treatment operations. A fixture for thermo-mechanical treatment of long low-rigidity shafts was designed and used in tests which involved axial straightening of shafts combined with a quenching operation (performed to increase the corrosion resistance of the steel used as stock material). The study showed that an analysis of the initial deflections of semi-finished shafts of different dimensions and determination of the maximum corrective deflection in the device could be used as a basis for performing axial straightening of shaft workpieces with simultaneous heat treatment and correction of the initial deflection of the workpiece. The deflection is corrected by stretching the fibers of the stock material, at any cross-section of the shaft, up to the yield point and generating residual stresses symmetrical to the axis of the workpiece. These processes allow to increase the accuracy and stability of the geometric shape of the shaft.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Long low-rigidity shafts are manufactured from bar stock with substantial curvature. They are commonly used in the aerospace industry, precision mechanics, the automotive industry, and as special tools. Shafts of this type have an irregular shape and are characterized by a low stiffness in specific cross-sections and directions (Jaworski et al. 2016; Litak et al. 2004).

The experiences of manufacturing such elements in short-series production and serial production in industrial settings show that the methods traditionally used in the machining of rigid parts are not very effective when it comes to the production of low-rigidity parts (Morozow et al. 2020; Taranenko et al. 2010). They increase the labor-intensiveness of machining, without ensuring the required quality of the finished products. Low rigidity shafts are more and more commonly used in various machines and mechanisms, especially precision devices (Świć et al. 2019). Continuous improvement of strength calculation methods, optimization of the shape and design of shafts, and a reduction in the amount of stock material required for their production all allow to increase the production volume of these parts (Fuglicek 2019).

Disproportions in the design parameters of long low-rigidity shafts lead to serious difficulties in the manufacture of these parts. These difficulties are associated with large elastic and plastic deformations generated at all stages of their machining, assembly and operation as well as low resistance to vibrations (Hassui and Diniz 2003; Ma et al. 2017). Moreover, differences in the response of the components of the technological system to machining, considerable effect of technological heredity on operational reliability, warping of semi-finished products caused by uneven residual stresses generated at all stages of machining, and low thermal stability of parts make the process complex and not easy to control (Zhao et al. 2020; Ye et al. 2020).

All these factors have an adverse impact on the production of long low-rigidity shafts, leading to defects in the shape, dimensions and surface properties of the products, reduced machining performance and efficiency, insufficient use of the accuracy potential of the machine tool and the life of its tooling, and, ultimately, a lowered quality of manufactured shafts (Ma et al. 2017; Bobrowskii et al. 2020). The workpiece is the weakest link in the technological system. It is subject to considerable elastic and plastic deformations which produce defects in the shape and dimensions of the workpiece at all stages of the technological process (Li and Shin 2006; Świć et al. 2014).

Research on methods of increasing the efficiency and quality of finished products manufactured in a traditional way, as well as the results of studies on their industrial application show that machining processes can be intensified by: selecting technological parameters and process conditions that allow to obtain the required accuracy of shafts (Zhang et al. 2019; Świć et al. 2017; Taranenko et al. 2010); developing alloys with a high dimensional stability, relatively low and stable thermal expansion coefficients (Tong et al. 2018), and a high elastic modulus (Vrancken et al. 2012); and using appropriate stabilizing treatment operations (Jianliang and Rongdi 2006; Urbicain et al. 2012).

In the response to the mentioned low-rigidity shafts production problems, there is a need to develop the new stabilization method that will allow level low-rigidity shafts deformation. The reduction of initial shaft deflection results in improved machining process efficiency and quality of produced parts.

Problem formulation

During long low-rigidity shafts machining the complex technological operations of stabilization are indispensable, because changes in the shape and dimensions of the workpiece lead to changes in input parameters and a decline in the reliability of precision machines. The typical disadvantage is warping (curvature of the axis of the workpiece occuration), which has an effect on the machining process. In the consequence, there is a need to develop appropriate method that combines straightening and heat treatment processes to increase the accuracy and stability of the geometric shape of shaft workpiece.

In this paper the new method of thermo-mechanical treatment of long low-rigidity shafts, which allows to obtain the required shape and dimensional parameters and ensures a high machining efficiency was presented.

The specific characteristics of the process of machining of low-rigidity shafts and accuracy requirements

The complex mechanical state of stock material during heat treatment, in combination with the variety of phase states it goes through, can lead to dimensional changes during the successive mechanical operations or storage. Free warping can also occur after heat treatment, initially often in a specific direction (bending, stretching), before phase transformations and inelastic deformations have taken place (Rudawska and Jacniacka 2018).

To minimize warping (deformation) of low-rigidity shafts during heat treatment under loading, conditions for the occurrence of an appropriate plastic deformation or phase transformation should be created (Wang et al. 2019). For example, during the martensitic transformation, steel loses tensile strength and undergoes a slight deformation (σ02 is reduced by 12 to 14 times) (Swic et al. 2016b). At quenching temperatures, the residual stress field is reduced to zero and is uniform across the cross-section of the workpiece; the layer that has been work-hardened by cold working is eliminated (Świć et al. 2019; Bobrowskii et al. 2020). It is technologically difficult to maintain such a state of the material when cooling to ambient temperature, because during cooling with the load removed, the condition of conformity of plastic-elastic deformations is not met. In this case, the specific technological features of the process of preparing the workpiece for heat treatment should be analyzed. It is important that the geometrical parameters of the workpiece after straightening and machining do not exceed semi-finishing tolerances (Świć et al. 2016). Non-uniform deformations are generated across the cross-section and along the length of the workpiece as a result of inaccurate machining (especially the eccentricity of the workpiece, i.e. the difference between the actual technological axis and the theoretical axis) (Wang et al. 2019). Under loading, the lack of symmetry in the cross-section generates a bending moment (Świć et al. 2019).

The sequential technological operations (processes) were considered, with axial strain applied to heated and non-heated material. Each of the operations considered can be performed autonomously, depending on the intended use of the product. The essence of the first technological process is that under tension, all longitudinal forces are equivalent in the first approximation, i.e., the same stresses are produced (Fig. 1a). The value of working stress σr can be determined from a stress–strain curve in relation to strain εp (Fig. 1c).

In curved segments, the stock material is straightened, despite tension, as a result of which, the strains in the longitudinal layers of these segments differ from one another. Usually, the radius of curvature is not less than 2–30 times the height of the cross-section of the workpiece, and so it can be assumed that the character of strain distribution in the cross-section of a shaft subjected to straightening is the same as in a rectilinear beam subjected to bending. The distribution of strain along the height of the workpiece is consistent with the linear relationship (Fig. 1b), and the minimum and maximum strains in the outer and inner layers of the shaft are given by:

where rk—radius of curvature of the workpiece.

The values of elongation fall within the range represented in the stress–strain curve by zone εδ–εm (Fig. 1c). It can be assumed that the tangent modulus of longitudinal elasticity Ey is constant. In this case, the stress distribution along the shaft height also corresponds to the linear relationship (Fig. 1b). Stresses in the deformation zone are given by:

where Ey \({\mathrm{E}}_{\mathrm{y}}\)—tangent modulus of longitudinal elasticity, E—Young's modulus, v—stress coordinate relative to the central layer of the workpiece.

The tensile force and bending moment can be determined from formula:

where S—cross-sectional area of the shaft, E·J—flexural rigidity of the shaft.

As a result of non-uniform distribution of stresses along the diameter of the curved segments of the workpiece, the part is subjected to an internal moment that needs to be counterbalanced by an external bending moment. This latter moment arises as the center of gravity of the cross-section of a shaft segment is shifted in relation to the line along which the tensile force is acting. In this case, the bending moment produced by the external forces is Mext = Ft·ye, where ye is the absolute value of a “part” of the final curvature that can be represented by known values:

where J—moment of inertia.

ye is only the “part” of the final curvature that remains after straightening. The main “part” of the final curvature forms as a result of relaxation of residual stresses and inelastic effects after the external tensile load has been removed. The previously bent sections of the shaft partly recover their curvature, as the removal of the tensile forces is accompanied by the removal of the bending moment originating from the action of these forces.

The results of the analytical study of axial deformation of the shaft show that the final curvature of the product depends on the initial curvature \(\frac{1}{{r_{k} }}\) of the workpiece, the physico-mechanical properties of the stock material, and the manufacturing technology used. In this context, several approaches to the design of technological processes for machining low rigidity shafts can be mentioned, which take into account the characteristics of the stock material. In the case of stock materials with a growing characteristic, the external tensile load should be determined for the zone of elongations εδ–εm corresponding to the segment of the σ–ε curve, which has a minimum tangent modulus of longitudinal elasticity. For low carbon steels, this is the yield zone (Ey = 0). When determining the axial deformation of materials prone to work-hardening, zone εδ–εm in the σ–ε curve should be located after the initial section with a steep slope of the stress curve. High-carbon and high-alloy steels are characterized by a steep increase in stress over a section of uniform elongation. They have high values of the tangent modulus of longitudinal elasticity, which means they require high axial loads, and these, in turn, lead to deformations that significantly exceed the material's ultimate tensile strength.

This technological approach can be used as a roughing process to improve the curvature of axisymmetrical shafts with a ratio of \(\frac{L}{d} \le 100\) which are not prone to work-hardening.

A method combining straightening and heat treatment was developed that allows to increase the accuracy and stability of the geometric shape of low-rigidity parts (Świć et al. 2014, 2016a). In essence, the method consist in applying axial strain (tension) to the shaft during heating (at quenching temperature), and aligning the workpiece relative to the fixture during the cooling stage, with the shaft cooling down several times faster than the fixture (Fig. 2a). Figures 2 and 3, show fixture 1 and workpiece 2, and their heating and cooling characteristics.

For theoretical calculations, it was assumed that the curvature of the axis of the workpiece is described by a sine wave:

and the change in the length of the semi-finished product is given by the following equation (Fig. 2a)

where α—initial deflection.

When a workpiece with an initial curvature of not more than 1% is stretched over length L, the value of deformation yα1 is connected with the initial curvature yα by equation:

which can be used to determine the axial load necessary to reduce deflection

where: Fcr—critical axial force.

The stress–strain curve can be used provided that inequality (9) is met

if λ < 100, then the axial tensile force should be determined from the equation:

The calculation data show that the material (e.g. stainless steel) of a workpiece with a diameter of 60 mm and a length of 3000 mm, for which σ02 = 200 N/mm2, can be deformed to its proportional limit by applying an axial load of 6·105 N. This means that apart from the already mentioned shortcomings, the process of axial deformation has yet another disadvantage of requiring a high-power drive unit. The proposed techniques make use of the physical principles of heat treatment: axial deformation of a workpiece is generated by carefully selecting the thermal expansion coefficients of the workpiece and the fixture as well as the lengths of these elements (the workpiece is placed in the fixture, with its ends mounted on the faces of the fixture—Fig. 2a). The difference in the elongation of the blank and the fixture is given by:

An analysis of the curve in Fig. 3a shows that as the heating temperature rises, the difference in elongation values also increases in a non-linear manner. To stabilize the geometry of the product, the total elongation generated in the fixture during heat treatment should not be less than 1% of the fixture's length.

During heating, the workpiece is elongated by:

where the following symbols stand for elongation associated with: \(\Delta_{1}\)—initial curvature of the workpiece; \(\Delta_{2}\)—difference between thermal expansion coefficients of workpiece and fixture materials; \(\Delta_{02}\)—arbitrarily defined proportionality interval at T° = 20 °C; \(\Delta_{3}\)—elongation of the workpiece; K1 = S + S/Sfix—fixture compression coefficient.

In the method proposed here, the shaft deforms upon heating at a pre-determined rate defined for the heat treatment technology used. The fixture elongates to a greater extent than the workpiece, proportionally to the difference in their linear expansion coefficients, and cools down 1.5 to 3 times slower than the shaft. This allows to stabilize the axial load at the start of cooling and remove the load gradually. When calculating typical processes, it is necessary to solve the problem of non-stationary thermal conductivity, i.e. to define the relationship between the change in temperature and the amount of heat transferred in time, at any point of a body. The differential equation of thermal conductivity for rigid bodies is as follows:

In order to solve analytical Eq. (13), the following boundary conditions should be determined: (1) initial temperature distribution in the material; (2) impact of the external environment on the surface of the body, which can be determined by: (a) measuring surface temperature, (b) measuring the amount of heat passing through the surface, and (c) measuring ambient temperature and calculating the heat transfer coefficient γ. According to Newton's law of cooling:

where dQ—amount of heat, \(T^{^\circ }_{fix}\), \(T^{^\circ }_{c}\)—temperature of fixture wall and liquid, dS—unit of surface area, b—thermal conductivity coefficient.

A solution of Eq. (13) is a function that should meet all the boundary conditions. The function sought depends on a large number of parameters that can be grouped into two dimensionless complexes:

-

the Biot criterion—\(B_{i} = \frac{{\gamma \delta_{p} }}{\phi }\),

-

the Fourier criterion—\(F_{0} = \frac{b \cdot t}{{\delta_{p} }}\),

where \(\varphi\)—thermal conductivity coefficient, δp—wall thickness of the fixture, t—cooling time.

Based on the second theorem of similarity, the function sought, which has the form of dimensionless temperature \(\frac{Q}{{Q^{\prime } }}\) at various points of a body can be represented as:

where: \(L = \frac{x}{\delta }\), x—coordinates of the heating zone.

A shaft can be represented as an infinitely long cylinder with a radius R, in which case, the differential equation of thermal conductivity has the form:

-

Boundary conditions: at r = R; \(\frac{\partial Q}{{\partial t}} = \gamma \frac{Q}{{\phi_{c} }}\).

-

Initial conditions: at t = 0; Q = Q′.

The relationship between the deformation of the fixture and the shaft during cooling is shown in the curve ε = ψ(T°) (Fig. 2b), where εult—deformation of the workpiece by εwp (Fig. 3b), when the linear expansion coefficients are different.

If the thermal expansion coefficients of the workpiece and the fixture are the same, then axial deformation can be obtained (in accordance with the calculations) as the difference between the lengths of the fixture and the workpiece or by appropriately selecting their cooling rates (Fig. 3a).

The axial tensile stress during heat treatment is determined from the formula:

where \(\Delta\) T—temperature difference between the workpiece and the fixture during cooling, \(\alpha_{T} = \alpha (T) + T\frac{d\alpha }{{dT}}\)—actual difference in thermal expansion coefficients.

When quenching a stepped shaft workpiece, the conditions for obtaining equal working stresses on all shaft steps are determined from the formula:

where \(S_{wp}^{n} ,S_{wp}^{n - 1} ,S_{fix}^{n} ,S_{fix}^{n - 1}\)—cross-sectional planes of workpiece and fixture at steps “n” and “n–1” of the workpiece.

At the first stage of cooling of a shaft secured in the fixture, when the temperature difference between the two is the largest, the value of small ultimate strains of the workpiece is the sum of elastic deformations εy, plastic deformations εpl and temperature deformations εT:

where

In the proposed heat treatment technology, which involves the application of axial strain, the stresses remaining from previous operations are eliminated (Lin et al. 2003), regardless of the properties of the material used. However, cooling of a stretched shaft secured in the fixture, generates new tensile stresses, which are uniformly distributed over the cross section of the workpiece. The level of ultimate stresses is given by:

During cooling, the outer part of the workpiece cools faster than the inner part, which means the stresses in the surface layers will be of the opposite sign to those inside the workpiece. After the workpiece has cooled down completely, the signs of the stresses are reversed. The main advantage of the proposed technology is that the stresses on the outside of the worpiece are of the same sign, which prevents the workpiece from warping. Further machining, with metal being removed evenly relative to the shaft axis, does not cause warping.

The equations presented above are valid assuming that the model is linear. A non-linear model, i.e. one in which plastic deformation during quenching under axial strain does not exceed 1%, allows to approximate this relationship with sufficient accuracy for practical purposes. Active control of the state of materials during heating and deformation of the workpiece allows to control the residual stresses throughout the entire machining time.

The overview of the method is presented in the Fig. 4. Developed solution includes two important knowledge-based modules which ensure an adaptational and intelligent character of the method. The important parameters are inputted in the three ways: defined by user (u), extracted from the database (d) and obtained from the sensors (s). Before the process of straightening the operator input geometrical parameters of the workpiece and fixture. In the next stage, the data about material parameters and assumed shaft deformation are extracted from the databases. The utilization of databases enables increased the pace of computation and previous process parameters storage. Inputted data are processed by means of appropriate equations and dependencies in both modules. The adaptational character of the proposed solution is implemented by means of calculated and measured tensile force value comparison. Conversion of thermal parameters to the current tensile stress value (tensile force in the consequence) provides better process control and appropriate shaft deformation correction.

The proposed method was designed taking into account the ease of its implementation with the use of the PC and common-used programming languages. This approach allows to combine computer realization of the method with the use of executive and regulation physical devices (Fig. 5).

A device for controlling plastic deformation of low rigidity shafts comprises a shaft furnace 1, with sectional electric heating elements 2. The workpiece 3 is positioned in a vee block and placed in the furnace. Ribs are pre-positioned on the workpiece to divide the shaft furnace space into chambers, with each chamber having a cooling air inlet and outlet.

After the workpiece has been fixed in position, the heating elements are turned on to heat it. The current temperature is measured with thermocouples mounted in each chamber. After the workpiece has been heated to temperature T° = 300 °C, the system that applies axial tension to the workpiece is activated.

Because the different segments along the length of the workpiece have different physico-mechanical properties, the time at which the yield point is reached may be different for the different parts of the shaft. The proportional limit of axial elongation is registered with a pneumatic gauge.

The electric heating sections are disconnected along the plastic strengthening zone of the workpiece, and a compressor which supplies cooling air is switched on. When the air-cooled section of the workpiece reaches temperature T° = 200 °C, the compressor is disconnected and the workpiece is heated again.

The developed method physical implementation is possible thanks to the utilization of sensors, measuring card, computer, PLC (Programmable Logic Controller), regulation and executive devices. Utilization of mentioned devices allow to appropriate process control. In the Fig. 5 only one segment measurement are shown, but in the real process data are obtained from all of the fixture elements.

The essence of the new method of thermo-mechanical treatment of long low-rigidity shafts

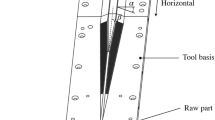

A workpiece 1, supported by steadies, is pre-machined on a lathe. Then the following outlines of working profiles 2 (Fig. 6) are formed:

-

a threaded outline—when determining the pitch, it is necessary to take into account the ultimate tensile strength of the stock material, the cross-sectional area of the workpiece, and the depth of the thread cut (internal diameter), which should not be greater than the stock allowed for finishing;

-

a stepped outline, in the case of which, the difference between the outer and inner diameters also depends on the ultimate tensile strength of the stock material and the cross-section of the workpiece, and should not be greater than the stock allowed for finishing.

In machining a workpiece with a thread, expanding collets 3 are screwed onto the workpiece; in the case of a stepped shaft, the expanding collets 3 are fitted over the workpiece in much the same way as a sleeve in a plain bearing (a collet consists of two parts). The collets are made of a material whose linear expansion coefficient αc is lower than the linear expansion coefficient of the stock material αwp.

The length of the collet is calculated taking into account the length of the part of the workpiece over which the collet is fitted and the condition of minimizing the deflection.

To achieve uniform compression along the axis of the workpiece and to obtain the required stiffness of the compressed part of the workpiece, a collet is used whose length is the same as the length of the shaft, and the length-to-diameter ratio of the shaft is not greater than 8: \(l_{1} = l_{2} ,\;\;\frac{l}{d} \le 8\). The collets 3 have ports 9 which are shaped and positioned in such a way as to allow the supply of cooling liquid at any mutual position of two adjacent collets.

The workpiece 1 with the expanding collets 3 (threaded collets are used with threaded workpieces, and two-piece expanding collets are used with stepped parts) is inserted (at a predetermined clearance value) into a multi-layer cylinder 4 and aligned relative to its upper and lower face. The special cylinder 4 is made of a material which has the same linear expansion coefficient as the collets (to eliminate jamming due to temperature deformations) and is filled with a filler 5. The filler 5 can have different thermal conductivity coefficients (for instance, it can consist of river sand mixed with cast iron chips).

The body of the cylinder 4 is multilayered, with each layer having an additional volume filled with material with a lower thermal conductivity coefficient. The cylinder is made of a material whose linear expansion coefficient is greater than that of the workpiece.

The multilayer body of the cylinder has ports in the longitudinal and transverse directions in which collets, made of the same material as the cylinder, are mounted. The internal diameter and the number of collets are determined from the condition of the technological process used (hardening, tempering, etc.), taking into account the geometrical parameters of the workpiece (e.g. a smooth or a stepped shaft). The workpiece can be secured in the cylinder in two ways:

-

the shaft can be aligned relative to the bottom face of the cylinder by means of a spherical surface fixed rigidly to a cover 6 on the bottom face of the cylinder, so that the lower end of the workpiece rests against the spherical surface and thus is in point contact with the cylinder;

-

the shaft can be aligned relative to the two faces of the cylinder by means of two spherical surfaces 7 rigidly fixed to covers 6 on the top and bottom faces of the cylinder. Secured in this way, the element is rigidly axially connected with the cylinder.

Four eye rings 8 for suspending the fixture are welded to the upper part of the cylinder 4. To avoid deflection of the workpiece 1 caused by stress generated during the heating/cooling of the workpiece–expanding collets–cylinder system, the clearance between collets 3 and cylinder 4 should only be large enough to allow the device to work without jamming.

The assembled device is placed in a shaft furnace and heated, in accordance with the heat-treating technology, to a quenching or tempering temperature, and then heat-soaked at this temperature until the whole workpiece has been heated. During heating, the workpiece expands lengthwise to a greater degree than do the collets and the cylinder, due to the difference in their linear expansion coefficients. By selecting appropriate numerical values of the positive difference in linear thermal expansion coefficients of the workpiece and the collets, one can obtain a value of plastic deformation of the workpiece which exceeds the proportional limit, i.e. the limit up to which Hooke's law holds. During heating, axial plastic deformation beyond the proportional limit (Hooke's law) eliminates the effects of technological heredity from preceding operations. In addition, as a result of the action of axial loads, the stock material undergoes work-hardening (cold-working) and the internal micro-cracks are eliminated.

The cylinder with the workpiece inside it is cooled down to a predetermined temperature; the difference between the cooling times of the workpiece and the cylinder is reversed/changed, while maintaining the axial state of stresses of the stock material until it is fully cooled. In the process, curved workpieces are straightened.

In contrast to other methods, in which workpieces undergo plastic deformation during cooling, the cylinder cools down earlier than the shaft, and the residual stresses have a local character; the essence of this technology is that the technological treatments are used in a reversed order (Li and Shin 2006).

In the proposed technology, plastic deformation occurs when the cylinder and shaft are heated at a predetermined rate, with the cylinder expanding lengthwise to a greater extent than the shaft, as determined by the linear thermal expansion coefficients of the two elements and the difference in length between the cylinder and the workpiece. During cooling, the cylinder cools down at a rate that is at least five times slower than the cooling rate of the workpiece (the latter should be cooling down at least five times faster than the fixture, depending on the cooling medium: oil, water, or air). When the axially loaded workpiece is cooling down, residual stresses are generated in it: alternating-sign stresses along the length of the shaft and uniform stresses in the cross-section, which prevents warping of the finished part during its operation.

To enhance the technological potential of the thermo-mechanical treatment, the multi-layer cylinder is assembled from segments, the number of which can be increased to make the cylinder longer if it is necessary to increase the length of the workpiece and the value of plastic deformation.

Example and result discussion

To verify presented solution the appropriate parameters calculation was conducted. An analysis was performed of heat transfer by a cylindrical pin fin with a cross- sectional area S = \(\pi\)·R2 and a cross-sectional perimeter U = 2π·R, (R—radius of the shaft).

Stock material: X10CrNi18-8 steel, density—γ = 7900 kg/m3, thermal conductivity coefficient—λs = 14.5 W/m·°C, specific heat capacity—C = 0.5 kJ/kg·°C, coefficient of heat transfer from the air to the shaft—ψB = 6 W/m2·°C thermal conductivity coefficient—µ = 5·10–6 m2/s.

The temperature of the pin fin was a function of its length only:

The principle of temperature change along the length of the pin fin and the amount of heat transferred by the pin fin in the stationary mode were determined.

Element dx was designated at distance x from the beginning of the segment (Fig. 7), and a thermal equilibrium equation was formulated for it:

In accordance with the Fourier principle,

and so

but also

By comparing (25) and (26) we obtained:

where

The solution of Eq. (27) can be written down as:

The values of the coefficients C1 and C2 are determined from the boundary conditions.

For a pin fin with a round cross-section and an infinite length:

where x—current coordinate, T° = T° − Tamb—ambient temperature, T0° = T0° − Tair—initial temperature, T°—current temperature, T0° = 300 °C, Tair = 30 °C.

The temperature curve equation for these conditions has the following form:

Equation (31) is used to determine the length of segment x along which the temperature will be set at T° = 200°:

A calculation scheme for determining the cooling time of a shaft segment is shown in Fig. 8.

Amount of heat transferred through the cross section:

Criterion of shaft segment cooling time:

When the equation is used for low values of Bi, the following relationship is obtained:

where: T° = 200° − 30° = 170 °C, T′ = 300° − 30° = 270 °C.

Equation (32) is used to determine the cooling time of the shaft segment.

The amount of heat absorbed by the air during complete cooling of a shaft segment with a length L = 300 mm at T′ = 100 °C is calculated from the formula:

The amount of heat flowing through the cross section (Qcs) from the hot to the cool side over time t = 90 s is determined from the formula:

Temperature elongations are given by:

where ΔL—difference in elongation between shaft and collet, T°—heating temperature, L—length of collet and shaft section.

Value of plastic deformation:

at L = 20 mm, T° = 1050 °C, αwp = 18.5·10–6 mm/mm·°C, αc = 12.8·10–6 mm/mm·°C.

Value of plastic deformations:

Cooling time was calculated for a system with the following parameters: shaft diameter 40 mm, internal diameter of the cylinder 160 mm, external diameter of the cylinder 260 mm, filler—sand mixed with cast iron chips, cooling agent—oil at 30°. The cooling time of the shaft was determined from the formula:

The cooling time of the cylinder was determined by solving the equation:

where \(F_{0} = \frac{\alpha ^{\prime}}{{r^{2} }}\)—Fourier criterion, defined as a function of relative temperatures \(\frac{{\theta_{0} }}{{\theta^{\prime } }}\), \(B_{i} = \frac{{B_{0} }}{{\lambda_{eq} }}\)—Biot criterion, r—diameter of a long shaft (in this case the shaft is represented as an infinitely long cylinder with radius δ), λeq—equivalent thermal conductivity of the collet–multilayer cylinder system, B0—coefficient of heat transfer from the environment to the surface of a body, γ—specific gravity of the material.

The difference in the coefficients of thermal expansion αwp and αc between the material of the collet and cylinder and the stock material was positive over the entire heat treatment cycle.

Figure 9 compares internal stresses in the shaft before and after the application of thermo-mechanical treatment. The treatment also improves the strength characteristics of shafts.

Changes in the level of residual stresses in the shaft before and after thermo-mechanical treatment: a workpiece aligned and secured relative to the bottom face of the cylinder by means of a spherical surface; b workpiece aligned and secured relative to the top and bottom face of the cylinder by means of two spherical surfaces

The new thermo-mechanical treatment technology allows to minimize the deflection of the workpiece and stabilize the level of residual longitudinal stresses, and in this way to increase the operational accuracy and quality of finished products, such as long low-rigidity shafts.

The calculation scheme presented above as well as the tests and calculations show that straightening-heating of shaft workpieces in the proposed fixture allows to increase the accuracy of low-rigidity shafts and stabilize their geometric shape.

Conclusions

The article presents an original technology of thermo-mechanical treatment of low-rigidity shafts that combines straightening and heat treatment processes to increase the accuracy and stability of the geometric shape of shaft workpieces. The essence of this new method is that the shaft is deformed (put into axial tension) during heating and is then held in a special fixture while it cools down. The cooling rate of the shaft is several times higher than that of the fixture. This allows to straighten the workpiece axially while it is being subjected to heat treatment, and to reduce its initial deflection by stretching the fibers in the cross-section up to the yield point and generating residual stresses in the workpiece symmetrical to its axis. The proposed technology differs from other known methods in that it uses the technological treatments in a reversed order. In the proposed technology, plastic deformation occurs when the cylinder and shaft are heated at a predetermined rate and the cylinder expands lengthwise to a greater extent than the shaft, depending on the value of the linear thermal expansion coefficients and the difference in length between the cylinder and the shaft.

The new thermo-mechanical treatment technology allows to minimize the deflection of the workpiece and stabilize the level of residual longitudinal stresses, increasing in this way operational accuracy and improving the quality of finished shafts.

The tests carried out using the new fixture for thermo-mechanical treatment show that shafts subjected to axial straightening combined with quenching (performed to increase the corrosion resistance of steel) deform during heating at a predetermined rate specified for the heat treatment technology used. The experiments confirmed the validity of the newly developed technology of thermo- mechanical treatment of long shafts.

References

Bobrowskii, A., Drachev, O., & Kravtsov, A. (2020). Stand for optimization of thermo-force processing of shafts. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 709(4), 1–5.

Fuglicek, L. (2019). Increase of production productivity using the combined machining in one clamping. MM Science Journal. https://doi.org/10.17973/MMSJ.2019_10_2019038.

Hassui, A., & Diniz, A. E. (2003). Correlating surface roughness and vibration on plunge cylindrical grinding of steel. International Journal of Machine Tools Manufacturing, 43, 855–862.

Jaworski, J., Kluz, R., & Trzepieciński, T. (2016). Operational tests of wear dynamics of drills made of low-alloy highspeed HS2-5-1 steel. Eksploatacja i Niezawodnosc—Maintenance and Reliability, 18(2), 271–277.

Jianliang, G., & Rongdi, H. (2006). A united model of diametral error in slender bar turning with a follower rest. International Journal of Machine Tools Manufacturing, 46(9), 1002–1012.

Li, H., & Shin, Y. C. (2006). A comprehensive dynamic end milling simulation model. Journal of Manufacturing Sciences Engineering, 128(1), 86–95.

Lin, C. W., Tu, J. F., & Kamman, J. (2003). An integrated thermomechanical-dynamic model to characterize motorized machine tool spindles during very high speed rotation. International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture, 43(10), 1035–1050.

Litak, G., Rusinek, R., & Teter, A. (2004). Nonlinear analysis of experimental time series of a straight turning process. Meccanica, 39(2), 105–112.

Ma, C., Zhang, L., Bao, C., Jiang, Y., & Xiao, X. (2017). Vibration modal shapes and strain measurement of the main shaft assembly of a friction hoist. Journal of Vibroengineering, 19(8), 6252–6261.

Morozow, D., Siemiątkowski, Z., Gevorkyan, E., Rucki, M., Matijošius, J., Kilikdevičius, A., et al. (2020). Effect of yttrium and rhenium ion implantation on the performance of nitride ceramic cutting tools. Materials, 13(20), 4687.

Rudawska, A., & Jacniacka, E. (2018). Evaluating uncertainty of surface free energy measurement by the van Oss-Chaudhury-Good method. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives, 82, 139–145.

Swic, A., Draczew, A., & Gola, A. (2016). Method of achieving accuracy of thermo-mechanical treatment of low-rigidity shafts. Advances in Science and Technology. Research Journal, 10(29), 62–70.

Świć, A., Gola, A., & Hajduk, M. (2016). Modelling of characteristics of turning of shafts with low rigidity. Applied Computer Science, 12(3), 61–73.

Świć, A., Gola, A., Wołos, D., & Opielak, M. (2017). Microgeometry surface modelling in the process of lowrigidity elastic-deformable shafts turning. Iranian Journal of Science and Technology-Transactions of Mechanical Engineering, 41(2), 159–167.

Świć, A., Sobaszek, Ł, & Gola, A. (2019). Thermomechanical treatment of long low-stiffness shafts. IFAC-PapersOnLine, 52(10), 136–141.

Świć, A., Wołos, D., Zubrzycki, J., Opielak, M., Gola, A., & Taranenko, V. (2014). Accuracy control in the machining of low rigidity shafts. Applied Mechanics and Materials, 613, 357–367.

Taranenko, G., Taranenko, W., Świć, A., & Szabelski, J. (2010). Modelling of dynamic systems of low-rigidity shaft machining. Eksploatacja i Niezawodnosc—Maintenance and Reliability, 4(48), 4–15.

Tong, D. M., Gu, J. F., & Yang, F. (2018). Numerical simulation on induction heat treatment process of a shaft part: Involving induction hardening and tempering. Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 262, 277–289.

Urbicain, G., Olvera, D., Fernandez, A., Rodruguez, A., Tabernero, I., & Lopez de Lacalle, L. N. (2012). Stability lobes in turning of low stiffness components. Advanced Materials Research, 498, 231–236.

Vrancken, B., Thijs, L., Kruth, J. P., & Van Humbeeck, J. (2012). Heat treatment of Ti6Al4V produced by selective laser melting: Microstructure and mechanical properties. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 541, 177–185.

Wang, Y. X., Yang, Z., Dai, J. W., Zhao, X. M., & Mao, X. Y. (2019). Research on surface strengthening induced by ultrasonic punching to improve mechanical properties and corrosion resistance for shaft parts. Surface Review and Letters, 27(01), 1950086.

Ye, Y., Hu, T., Yang, Y., Zhu, W., & Zhang, C. (2020). A knowledge based intelligent process planning method for controller of computer numerical control machine tools. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, 31, 1751–1767.

Zhang, Z., Cai, L., Cheng, Q., Cheng, Q., Liu, Z., & Gu, P. (2019). A geometric error budget method to improve machining accuracy reliability of multi-axis machine tools. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, 30, 495–519.

Zhao, Z., Wang, S., Wang, Z., Wang, S., Ma, C., & Yang, B. (2020). Surface roughness stabilization method based on digital twin-driven machining parameters self-adoption adjustment: A case study in five-axis machining. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-020-01698-4.

Acknowledgements

The Project/research was financed in the framework of the Project Lublin University of Technology-Regional Excellence Initiative, funded by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (contract no. 030/RID/2018/19).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Świć, A., Gola, A., Sobaszek, Ł. et al. A thermo-mechanical machining method for improving the accuracy and stability of the geometric shape of long low-rigidity shafts. J Intell Manuf 32, 1939–1951 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-020-01733-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-020-01733-4