Abstract

This paper describes how the socioeconomic status (SES) of parents relates to the formation and development of the skills and preferences of their teenage children, which have proven to be key to understanding differences in life outcomes. The study used data from a novel survey, conducted in Mexico, that recorded cognitive and non-cognitive skills and social preferences of both parents and children. It analyzed the relationship between the SES of parents and their children’s skills, and found that children’s skills were consistently related to parental skills, and that intergenerational persistence of skills was higher for cognitive than for non-cognitive skills or social preferences. It also found that the cognitive skills gap between the first and fifth quintile of SES was related mainly to characteristics like parents’ own skills, years of schooling, and aspirations for their children, but that these parental characteristics were less important in explaining non-cognitive skills and preferences.

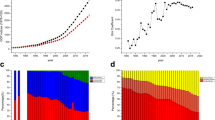

Source: Author’s calculations using SMS-2015

Source: Author’s calculations using SMS-2015

Source: Author’s calculations using SMS-2015

Source: Author’s calculations using SMS-2015

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Urban population is defined as that in communities of 100,000 or more inhabitants. The sample includes individuals from 23 states and 86 municipalities. The dataset is available at http://movilidadsocial.colmex.mx/. Torche (2014) describes the other datasets available for Mexico. These surveys only interview one adult in the household (not teenagers) and do not include a measurement of preferences, skills, or environment when growing up (stress in the household of origin). However, these datasets are nationally representative and not only at the urban level.

More precisely, 97.2% of the sample consists of parent–child relationships. The rest of the sample consists of relationships of stepparent–stepchild (1.5%), grandparent–grandchild (0.8%), aunt/uncle–nephew/niece (0.2%), and other relationships (0.3%).

I thank an anonymous reviewer for this observation.

Results were similar using a simple average or a principal component analysis.

Complete regression results are reported in the supplementary materials. There was an age bonus in the intelligence results, as older teenagers scored better than younger ones. Also, girls scored 0.11 standard deviations lower than boys. Skill of the parent means the skill of either the mother or father.

This methodology has a long tradition in sociology (Alwin and Hauser 1975; Duncan 1966), and recently in economics, in decompositions of intergenerational transmission coefficients (Mood et al. 2012). This decomposition is different from the traditional Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition. The latter separates the contribution of observable characteristics and returns, while the former distinguishes how much of the socioeconomic gradient is accounted for by observable characteristics.

References

Almlund, M., Duckworth, A. L., Heckman, J. J., & Kautz, T. (2011). Personality psychology and economics. In E. A. Hanushek, S. Machin, & L. Woessmann (Eds.), Handbook of economics of education (Vol. 4, pp. 1–181). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Alwin, D., & Hauser, R. (1975). The decomposition of effects in path analysis. American Sociological Review, 40(1), 37–47. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2094445.

Anger, S. (2011). The intergenerational transmission of cognitive and non-cognitive skills during adolescence and young childhood. (IZA Discussion Paper 5749). Retrieved from http://ftp.iza.org/dp5749.pdf.

Anger, S., & Heineck, G. (2010). Do smart parents raise smart children? The intergenerational transmission of cognitive abilities. Journal of Population Economics, 23(3), 1105–1132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-009-0298-8.

Anger, S., & Schnitzlein, D. D. (2013, January). Like brother, like sister? The importance of family background for cognitive and non-cognitive skills. Paper presented at the German Economic Association Annual Conference 2013: Competition Policy and Regulation in a Global Economic Order, Dusseldorf, Germany. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10419/80052.

Becker, A., Deckers, T., Dohmen, T., Falk, A., & Kosse, F. (2012). The relationship between economic preferences and psychological personality measures. Annual Review of Economics, 4(1), 453–478. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080511-110922.

Blanden, J., Gregg, P., & Macmillan, L. (2007). Accounting for intergenerational income persistence: Noncognitive skills, ability and education. The Economic Journal, 117(519), C43–C60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2007.02034.x.

Bowles, S., Gintis, H., & Groves, M. (Eds.) (2005). Unequal chances: Family background and economic success. New York: Princeton University Press. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7tbdz.

Caliendo, M., Cobb-Clark, D. A., & Uhlendorff, A. (2015). Locus of control and job search strategies. Review of Economics and Statistics, 97(1), 88–103. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00459.

Campos-Vazquez, R. M. (2016). Guía del usuario: Encuesta de movilidad social 2015. Retrieved from http://movilidadsocial.colmex.mx/images/encuesta/guia-emovi2015.pdf.

Carvalho, L. (2012). Childhood circumstances and the intergenerational transmission of socioeconomic status. Demography, 49(3), 913–938. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0120-1.

CEEY [Centro de Estudios Espinosa Yglesias]. (2013). Informe movilidad social en México: Imagina tu futuro. Mexico City: Centro de Estudios Espinosa Yglesias.

Cesarini, D., Dawes, C. T., Johannesson, M., Lichtenstein, P., & Wallace, B. (2009). Genetic variation in preferences for giving and risk taking. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(2), 809–842. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2009.124.2.809.

Charness, G., Gneezy, U., & Imas, A. (2013). Experimental methods: Eliciting risk preferences. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 87, 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2012.12.023.

Cobb-Clark, D. A. (2015). Locus of control and the labor market. IZA Journal of Labor Economics, 4(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40172-014-0017-x.

Corak, M. (2013). Income inequality, equality of opportunity, and intergenerational mobility. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(3), 79–102. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.27.3.79.

Crawford, C., Goodman, A., & Joyce, R. (2011). Explaining the socio-economic gradient in child outcomes: The inter-generational transmission of cognitive skills. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 2(1), 77–93. https://doi.org/10.14301/llcs.v2i1.143.

Cunha, F., & Heckman, J. J. (2009). The economics and psychology of inequality and human development. Journal of the European Economic Association, 7(2–3), 320–364. https://doi.org/10.1162/jeea.2009.7.2-3.320.

Currie, J. (2009). Healthy, wealthy, and wise: Socioeconomic status, poor health in childhood, and human capital development. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(1), 87–122. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.47.1.87.

Deckers, T., Falk, A., Kosse, F., & Schildberg-Hörisch, H. (2015). How does socio-economic status shape a child’s personality? (IZA Discussion Paper 8977). Retrieved from http://ftp.iza.org/dp8977.pdf.

Dohmen, T., Enke, B., Falk, A., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2015). Patience and the wealth of nations. Retrieved from http://humcap.uchicago.edu/RePEc/hka/wpaper/Dohmen_Enke_etal_2016_patience-wealth-nations.pdf.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2012). The intergenerational transmission of risk and trust attitudes. The Review of Economic Studies, 79(2), 645–677. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdr027.

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1087–1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087.

Duckworth, A. L., & Quinn, P. D. (2009). Development and validation of the short grit scale (Grit–S). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802634290.

Duncan, O. D. (1966). Path analysis: Sociological examples. American Journal of Sociology, 72(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1086/224256.

Duncan, G., Kalil, A., Mayer, S. E., Tepper, R., & Payne, M. R. (2005). The apple does not fall far from the tree. In S. Bowles, H. Gintis, & M. O. Groves (Eds.), Unequal chances: Family background and economic success. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ermisch, J., Jäntti, M., & Smeeding, T. (Eds.) (2012). From parents to children: The intergenerational transmission of advantage. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7758/9781610447805.

Falk, A., Becker, A., Dohmen, T., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2016). The preference survey module: A validated instrument for measuring risk, time, and social preferences. (IZA Discussion Paper 9674.) Retrieved from http://ftp.iza.org/dp9674.pdf.

Fehr, E., & Gächter, S. (2002). Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature, 415(6868), 137–140. https://doi.org/10.1038/415137a.

Filmer, D., & Pritchett, L. (1999). The effect of household wealth on educational attainment: Evidence from 35 countries. Population and Development Review, 25(1), 85–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.1999.00085.x.

Gasparini, L., & Lustig, N. (2011). The rise and fall of income inequality in Latin America. (Society for the Study of Economic Inequality, ECINEQ Working Paper 213.) Retrieved from http://www.ecineq.org/milano/wp/ecineq2011-213.pdf.

Golsteyn, B. H. H., Grönqvist, H., & Lindahl, L. (2014). Adolescent time preferences predict lifetime outcomes. The Economic Journal, 124(580), F739–F761. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12095.

Goodman, A., Gregg, P., & Washbrook, E. (2011). Children’s educational attainment and the aspirations, attitudes and behaviours of parents and children through childhood. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 2(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.14301/llcs.v2i1.147.

Grönqvist, E., Öckert, B., & Vlachos, J. (2017). The intergenerational transmission of cognitive and noncognitive abilities. Journal of Human Resources, 52(4), 887–918. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.52.4.0115-6882r1.

Guryan, J., Hurst, E., & Kearney, M. (2008). Parental education and parental time with children. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(3), 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.22.3.23.

Hanushek, E. A., Schwerdt, G., Wiederhold, S., & Woessmann, L. (2015). Returns to skills around the world: Evidence from PIAAC. European Economic Review, 73, 103–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2014.10.006.

Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore: Paul H. Brooks Publishing Co.

Heckman, J. J., & Kautz, T. (2012). Hard evidence on soft skills. Labour Economics, 19(4), 451–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2012.05.014.

Heineck, G., & Anger, S. (2010). The returns to cognitive abilities and personality traits in Germany. Labour Economics, 17(3), 535–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2009.06.001.

Loehlin, J. C. (2005). Resemblance in personality and attitudes between parents and their children: Genetic and environmental contributions. In S. Bowles, H. Gintis, & M. O. Groves (Eds.), Unequal chances: Family background and economic success. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

McKenzie, D. J. (2005). Measuring inequality with asset indicators. Journal of Population Economics, 18(2), 229–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-005-0224-7.

Mischel, W. (2014). The marshmallow test: Mastering self-control. New York: Little, Brown and Company.

Moffitt, T. E., Arseneault, L., Belsky, D., Dickson, N., Hancox, R. J., Harrington, H., et al. (2011). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(7), 2693–2698. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1010076108.

Mood, C., Jonsson, J., & Bihagen, E. (2012). Socioeconomic persistence across generations: Cognitive and noncognitive processes. In J. Ermisch, M. Jäntti, & T. Smeeding (Eds.), From parents to children: The intergenerational transmission of advantage. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7758/9781610447805.7.

Mosing, M. A., Pedersen, N. L., Cesarini, D., Johannesson, M., Magnusson, P. K. E., Nakamura, J., et al. (2012). Genetic and environmental influences on the relationship between flow proneness, locus of control and behavioral inhibition. PLoS ONE, 7(11), e47958. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0047958.

Ostrosky-Solís, F., & Lozano, A. (2006). Digit span: Effect of education and culture. International Journal of Psychology, 41(5), 333–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590500345724.

Piatek, R., & Pinger, P. (2010). Maintaining (locus of) control? Assessing the impact of locus of control on education decisions and wages. (IZA Discussion Paper 5289.) Retrieved from http://ftp.iza.org/dp5289.pdf.

Piff, P. K., Kraus, M. W., Côté, S., Cheng, B. H., & Keltner, D. (2010). Having less, giving more: The influence of social class on prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(5), 771–784. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020092.

Rammstedt, B. (2007). Who worries and who is happy? Explaining individual differences in worries and satisfaction by personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(6), 1626–1634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.04.031.

Rammstedt, B., & John, O. P. (2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.02.001.

Richardson, J. T. E. (2007). Measures of short-term memory: A historical review. Cortex, 43(5), 635–650. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70493-3.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcements. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0092976.

Schady, N., Behrman, J., Araujo, M. C., Azuero, R., Bernal, R., Bravo, D., et al. (2015). Wealth gradients in early childhood cognitive development in five Latin American countries. Journal of Human Resources, 50(2), 446–463. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.50.2.446.

Schipolowski, S., Wilhelm, O., & Schroeders, U. (2014). On the nature of crystallized intelligence: The relationship between verbal ability and factual knowledge. Intelligence, 46, 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2014.05.014.

Schurer, S., Kassenboehmer, S., & Leung, F. (2015, July). Testing the human capital model of education: Do universities shape their students’ character traits? Paper presented at the 44th Australian Conference of Economists (ACE 2015), Brisbane, Queensland. Retrieved from https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/conference/download.cgi?db_name=ACE2015&paper_id=68.

Suskind, D. (2015). Thirty million words: Building a child’s brain. New York: Penguin Random House.

Torche, F. (2014). Intergenerational mobility and inequality: The Latin American case. Annual Review of Sociology, 40(1), 619–642. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145521.

Torche, F. (2015). Intergenerational mobility and gender in Mexico. Social Forces, 94(2), 563–587. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sov082.

Turkheimer, E., Pettersson, E., & Horn, E. E. (2014). A phenotypic null hypothesis for the genetics of personality. Annual Review of Psychology, 65(1), 515–540. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143752.

Vischer, T., Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Schupp, J., Sunde, U., & Wagner, G. G. (2013). Validating an ultra-short survey measure of patience. Economics Letters, 120(2), 142–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2013.04.007.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for comments from Mariano Bosch, Isidro Soloaga, Sergio Urzua, and participants at the following conferences: “Skills: Measurements, Dynamics, and Effects,” hosted by the Latin American and Caribbean Economic Association; “The Intergenerational Transmission of Economic Status: Exposure, Heritability, and Opportunity,” organized by the Universidad Carlos III in Madrid; and the 2016 Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America. I also wish to thank Cristobal Domínguez for excellent research assistance and two anonymous reviewers and the editor for their thoughtful comments and suggestions. Any errors or omissions are solely my responsibility.

Funding

This work was supported by the Sectorial Fund for Research on Social Development of the Mexican National Council on Science and Technology (CONACyT) and the Secretary of Social Development (SEDESOL) (Project No. 217909). The Espinosa Yglesias Research Center provided financing for a research assistant and a roundtable with academics to discuss the survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Campos-Vazquez, R.M. Intergenerational Persistence of Skills and Socioeconomic Status. J Fam Econ Iss 39, 509–523 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-018-9574-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-018-9574-7