It wasn’t until the Nobel Prize that they really thawed out. They couldn’t understand my books, but they could understand $30,000. (William Faulkner).

Abstract

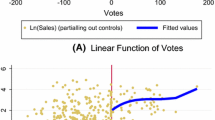

This paper analyses the effect of literary prizes and nominations on the subsequent market success using a panel dataset of Dutch-language titles from January 2003 to June 2005. The analysis indicates winning a prize generally has a positive effect on the ensuing sales, whereas nominations do not generate additional sales. The precise effect differs depending on the particular prize. Winning a “home” debut prize has a significant positive effect on sales, and, to a lesser extent, “established” literary prizes have a significant positive effect on the sales of the winning title, but winning a debut prize in the Netherlands, the neighbouring country, has no effect on sales in Belgium.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This number does not include publications that are not readily available in bookshops, such as scientific or company reports and dissertations.

It was not possible to retrieve sufficient data on the initial orders from the publishers involved. This means that, despite selecting successful authors for the sample for analysis, the impact is liable to be an even greater preponderance of zeros in the sample. The publishers split 68% Dutch and 32% Belgian.

The apparent inconsistency is because the Flemish author Erwin Mortier won both the ‘Debuutprijs’ and the ‘DebutantenPrijs’ in 2000. Similarly, for the prizes for established authors, Arnon Grunberg has won three prizes—the Gouden Uil in 2005 and the AKO prize in 2000 and 2004—and Jeroen Brouwers won both the Gouden Uil and the AKO prize in 2001.

To enable examination to be made solely of fiction, Dik van der Meulen, winner of the 2003 AKO prize, and Frank Westerman, winner of the 2005 Gouden Uil were excluded from the sample as they won with non-fiction books. In addition, sensitivity tests were placed on books over 10, 20 and 30 years old. Removing all books over 10 years old does not affect the general tenor of the results.

As discussed below, the effect of the prize (or nomination) may not be instantaneous, and there may be a lag in effect; the “t” subscript is provided for consistency.

It is possible to model this in a different manner to reflect the treatment effect of the prize, following Sorensen (2007), using an autoregressive process in which the autoregressive parameter is a function of covariates. Following this route does identify the effect of prizes but it does as easily allow the time dimension between the two countries to be as clearly modelled as is the case in the method adopted.

It can be seen that if the effects of the nominations (or prizes) are the same then a restricted version of the model will emerge with, for example, a dummy for established nominations and/or debut nominations.

Clearly, it is possible to examine the “after” effects of each prize or type of prize, debut or established, and this was considered though the results were in line with those reported, that is, insignificant. In addition, the effect of nominations was also examined and proved to be insignificant and so, for simplicity, is not reported in the paper. Also, the data mitigate against the effect here as it would reflect surprise positive sales as all other sales were in the initial orders, which are not available.

In previous work, it is generally the case that either lagged sales or the time since publication is introduced into the model, but not both, presumably because of collinearity between the variables. The authors can see no reason why this should necessarily be the case where re-orders are used, and there is no obvious collinearity in this sample (with a correlation coefficient of no more than −0.1 between the variables. Thus, the date is allowed to determine the appropriate underlying model of re-orders. It is of note that the basic model appears to be autoregressive as, even in the simplest model, time since publication is always insignificant (and jointly so in the case of the use of quadratic and linear terms).

We tested for the stationarity of the variables in our model using the Im-Pesaran-Shin unit root test for panel stationarity (Im et al. 2003). Results are available upon request; none of the variables is above I(1).

First differencing also removes time-invariant title characteristics such as the dummies indicating whether the title is a hardback (HB) or a thriller/detective (THR). We can, however, anticipate a different time path for the sales of, e.g., the thriller/detective genre or of hardback editions. To test for such different time patterns, the THR and HB dummy variables can be interacted with TSP, the number of months since publication, and TSP2. Hence, THR.TSP, THR.TSP2, HB.TSP and HB.TSP2 were included as explanatory variables in Eq. 2. As can be seen in the tables, from the tests of restrictions, tests for this difference were insignificant.

Ahn and Schmidt (1995) show that these instruments are consistent but not necessarily efficient, as use is not made of all available moment conditions. This opens up the possibility of using a full GMM estimator of the Arellano and Bond (1991) type. We consider the Anderson and Hsaio (1981) route to be sufficient in this case, as we estimate re-sales, which likely makes the characteristics of the titles to be less important. Previous work in this area has not considered endogeneity as explicitly (see Sorensen 2007). The use of instruments here is precautionary. Results using OLS are in line with those using the instruments and available on request.

It is possible to assume that nomination and/or prize have an enduring (non-diminishing) effect on sales by defining dummy variables equal to 1 from the month of announcement of the prize and shortlist onwards. As this is unlikely even for the short time period available for estimation, it is omitted.

It can be seen that this specification has the advantage over the second in that the variable cannot go negative as the third specification allows for the effect of the prize to occur and then diminish. It should be remembered that what is being modelled are the re-orders, not the actual demand. Thus, even if the purchasers take time to buy the books (and act as unto the second specification), it may be in the retailers’ interest to have the books in stock (and so they will act like the third). Because of the data, the model is more likely to reflect bookseller behaviour.

It is of note that, traditionally, there is a degree of asymmetry in that many Flemish novelists have their books published by a Dutch publisher but not the reverse. As an example, in the sample used in this paper, 135 editions of titles by Flemish novelists were published in the Netherlands, and 71 editions were published by a Flemish publisher, whereas no Dutch author had their titles published by a Flemish publisher.

This applies whatever lag is placed for the Dutch prizes.

This effect was examined for up 3 months with the “best” results occurring after one time period. Effectively, the length of the data set precludes examining further than this length and, clearly, while this result does not preclude an effect at a longer time period, it does show no “immediate” effect. The result in column (2) of Table 2, which shows a negative effect of winning a prize on the sales of other titles, is puzzling; the only explanation could be a drive towards the prize winning novel at the expense of other titles but it should be noted that the overall effect of the “other books” variables in this specification is insignificant and does not occur in the preferred results.

It should be noted that the time period for the turning point for the Dutch prizes is also unrealistically long which is further evidence that this is not a preferred result.

The variable S has 3.523 as mean and 26.647 as standard deviation. The minimum value equals 0; the maximum value equals 1,541. All the estimations presented use 12,783 observations. This is the maximum number of observations with the maximum lags explored.

While there is no overall significant effect and no significant difference between the two Dutch prizes, the individual results are even more anomalous in that whereas the Dutch debut prize and the AKO prize have no impact on book sales, we find a negative effect of the Libris prize on Flemish re-orders and this variable close to being significant at a 10% level of significance.

The results are available from the authors on request; they are dominated by the preferred results presented in Table 1 (column 3).

There is a small effect in the second term but what is clear is that the first term is insignificant. If lags are introduced into this specification, there is an marginally significant effect but the specification is dominated by the preferred result in Table 1.

In order to calculate the overall effect on sales in the first year, the coefficient should be multiplied by 3.10; for the first 6 months by 2.45 so it can be seen that the effect diminishes quickly.

If Sorenson approach is adopted, there are broadly comparable results to those of this paper to the extent that there are identifiable effects associated with the two Belgium prizes and the Netherlands prize for established authors and with no discernible effect for Dutch debut prizes. The effects are debut prize (0.836); established Belgium prize (0.487); established Dutch prize (0.529). The full results are available form the authors on request; The implied constant effect on the X covariates—on the basic model is 0.361—with time since publication being insignificant but negative, if account is taken of book differences but positive, yet insignificant, if this is not taken into account. This result—save for the significance—is in line with Sorensen (2007).

References

Ackerberg, D. A. (2003). Advertising, learning, and consumer choice in experience good markets: A structural empirical examination. International Economic Review, 44(3), 1007–1040.

Ahn, S. C., & Schmidt, P. (1995). Efficient estimation of models for dynamic panel data. Journal of Econometrics, 68, 5–27.

Anderson, T. W., & Hsaio, C. (1981). Estimation of dynamic models with error components. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 76, 598–606.

Arellano, M. (1989). A note on the Anderson–Hsaio estimator for panel data. Economics Letters, 31, 337–341.

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies, 58, 277–297.

Basuroy, S., Chatterjee, S., & Abraham Ravid, S. (2003). How critical are critical reviews? The box office effects of film critics, star-power, and budgets. Journal of Marketing, 67(4), 103–117.

Beck, J. (2007). The sales effect of word of mouth: A model for creative goods and estimates for novels. Journal of Cultural Economics, 31(1), 5–23.

Bittlingmayer, G. (1992). The elasticity of demand for books, resale price maintenance and the lerner index. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 148, 588–606.

Canoy, M., van Ours, J. C., & van der Ploeg, F. (2006). The economics of books. In V. Ginsburgh & D. Throsby (Eds.), Handbook of cultural economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Caves, R. E. (2000). Creative industries. Contracts between art and commerce. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Caves, R. E., & Greene, D. P. (1996). Brands’ quality levels, prices, and advertising outlays: Empirical evidence on signals and information costs. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 14(1), 29–52.

Chevalier, J. A., & Mayzlin, D. (2006). The effect of word of mouth on sales: Online book reviews. Journal of Marketing Research, 43, 345–354.

Clement, M., Proppe, D., & Rott, A. (2007). Do critics make bestsellers? Opinion leaders and the success of books. Journal of Media Economics, 20(2), 77–105.

Davidson, R., & MacKinnon, J. G. (1981). Several tests for model specification in the presence of alternative hypotheses. Econometrica, 49, 781–793.

De Grauwe, P., & Gielens, G. (1993). De prijs van het boek en de leescultuur (p. 12). Algemene Reeks: Centrum voor Economische Studiën, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven.

De Vany, A., & Walls, W. D. (1996). Bose–Einstein dynamics and adaptive contracting in the motion picture industry. Economic Journal, 106(439), 1493–1514.

Deuchert, E., Adjamah, K., & Pauly, F. (2005). For oscar glory or oscar money? Academy awards and movie success. Journal of Cultural Economics, 29(3), 159–176.

Dodds, J. C., & Holbrook, M. B. (1988). What’s an oscar worth? An empirical estimation of the effect of nominations and awards on movie distribution and revenues. In B. A. Austin (Ed.), Current research in film: Audiences, economics and the law (Vol. 4, pp. 72–88). Norwood, New Jersey: Ablex Publishing.

Ekelund, B. G., & Börjesson, M. (2002). The shape of the literary career: An analysis of publishing trajectories. Poetics, 30(5–6), 341–364.

Eliashberg, J., & Shugan, S. M. (1997). Film critics: Influencers or predictors. Journal of Marketing, 61(2), 68–78.

Fishwick, F., & Fitzsimmons, S. (1998). Report into the effects of the abandonment of the net book agreement. Cranfield: Cranfield School of Management.

Ginsburgh, V. A. (2003). Awards, success and aesthetic quality in the arts. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(2), 99–111.

Ginsburgh, V. A., & van Ours, J. (2003). Expert opinion and compensation: Evidence from a musical competition. American Economic Review, 93(1), 289–296.

Hjorth-Andersen, C. (2000). A model of the Danish book market. Journal of Cultural Economics, 24(1), 27–43.

Holbrook, M. B. (1999). Popular appeal versus expert judgments of motion pictures. Journal of Consumer Research, 26(2), 144–155.

Im, K. S., Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y. (2003). Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics, 115, 53–74.

Jin, G. Z., & Leslie, P. (2003). The effects of information on product quality: Evidence from restaurant hygiene cards. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118, 409–451.

Lancaster, K. (1966). A new approach to consumer theory. Journal of Political Economy, 74, 132–157.

Larceneux, F., & Vézina, R. (2000). Experiential labels: A response to non observability of cultural product quality. Paper presented at the FOKUS-ACEI joint symposium on incentives and information in cultural economics, January 27–29, Vienna, Austria.

Litman, B. R. (1983). Predicting success of theatrical movies: An empirical study. Journal of Popular Culture, 16, 159–175.

Litman, B. R., & Kohl, L. S. (1989). Predicting financial success of motion pictures: The ‘80 s experience. Journal of Media Economics, 2, 35–50.

McFadden, D. L., & Train, K. E. (1996). Consumers’ evaluation of new products: Learning from self and others. Journal of Political Economy, 104(4), 683–703.

Montgomery, C. A., & Wernerfelt, B. (1992). Risk reduction and umbrella branding. Journal of Business, 65, 31–50.

Nederlands Bibliografisch Centrum. (2002). Jaarverslag NBC, 2000–2002 [http://www.kb.nl/dnp/nbc/nbc-jv2002.html].

Nelson, R. A., Donihue, M. R., Waldman, D. M., & Wheaton, C. (2001). What’s an Oscar worth? Economic Inquiry, 39(1), 1–16.

Prag, J., & Casavant, J. (1994). An empirical study of the determinants of revenues and marketing expenditures in the motion picture industry. Journal of Cultural Economics, 18(3), 217–235.

Prieto-Rodríguez, J., Romero-Jordán, D., & Sanz-Sanz, J. F. (2004). Is a tax cut on cultural goods consumption actually desirable? Paper presented at the AEA Conference on the Econometrics of Cultural Goods, Padova, April 22–23, 2004.

Ravid, S. A. (1999). Information, blockbusters, and stars: A study of the film industry. Journal of Business, 72(4), 463–492.

Reddy, S. K., Swaminathan, V., & Motley, C. M. (1998). Exploring the determinants of broadway show success. Journal of Marketing Research, 35(3), 370–383.

Reinstein, D. A., & Snyder, C. M. (2005). The influence of expert reviews on consumer demand for experience goods: A case study of movie critics. Journal of Industrial Economics, 53(1), 27–51.

Ringstad, V., & Løyland, K. (2006). The demand for books estimated by means of consumer survey data. Journal of Cultural Economics, 30(2), 141–155.

Smith, S. P., & Smith, V. K. (1986). Successful movies: A preliminary empirical analysis. Applied Economics, 18(5), 501–507.

Sochay, S. (1994). Predicting the performance of motion pictures. Journal of Media Economics, 7(4), 1–20.

Sorensen, A. T. (2007). Bestseller lists and product variety: The case of book sales. Stanford graduate school of business. Journal of Industrial Economics, 55(4), 715–738.

Sorensen, A. T., & Rasmussen, S. J. (2004). Is any publicity good publicity? A note on the impact of book reviews. Working Paper: Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Szenberg, M., & Lee, E. (1987). Empirical estimation of demand and supply of books in the United States, 1966–1982. In D. V. Shaw, W. S. Hendon, & C. Richard Waits (Eds.), Artists and cultural consumers (pp. 207–215). Akron, Ohio: Association for Cultural Economics.

Wallace, W. T., Seigerman, A., & Holbrook, M. B. (1993). The role of actors and actresses in the success of films: How much is a movie star worth? Journal of Cultural Economics, 17(1), 1–28.

Werck, K., & Heyndels, B. (2007). Prizes for children’s books: Expert judgments by adults and children. Working Paper, Vrije Universiteit Brussel.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 2.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ashworth, J., Heyndels, B. & Werck, K. Expert judgements and the demand for novels in Flanders. J Cult Econ 34, 197–218 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-010-9121-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-010-9121-3