Abstract

The expansion of Neolithic stable isotope studies in France now allows distinct regional population-scale food patterns to be linked to both local environment influences and specific economic choices. Carbon and nitrogen isotope values of more than 500 humans and of animal samples also permit hypotheses on sex-biased human provenance. To advance population scale research, we here present the first study that draws together carbon (C), nitrogen (N), sulphur (S) and strontium (Sr), dental calculus, aDNA, and palaeoparasitology analysis to infer intra-population patterns of diet and provenance in a Middle Neolithic population from Le Vigneau 2 (human = 40; fauna = 12; 4720–4350 cal. BC) from north-western France. The data of the different studies, such as palaeoparasitology to detect diet and hygiene, CNS isotopes and dental calculus analysis to examine dietary staples, Sr and S isotopes to discriminate non-locals, and aDNA to detect maternal (mtDNA) versus paternal lineages (Y chromosome), were compared to anthropological information of sex and age. Collagen isotope data suggest a similar diet for all individuals except for one child. The provenance isotopic studies suggest no clear differences between sexes, suggesting both males and females used the territory in a similar pattern and had access to foods from the same environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Regional Background

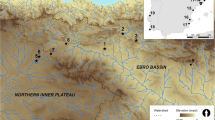

Over the last 15 years, the diet of individuals and populations from the Neolithic period in France has been studied with stable isotope analyses on human remains. Carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) stable isotope data have been used to define distinct regional food patterns linked to both local environment and specific economic choices, which has led to hypotheses of differential mobility of females during the Middle Neolithic (ca. 4500–3900 cal BC) (Goude 2007; Goude et al. 2013). Carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios of livestock vary due to local climate and substratum (e.g. temperature, precipitation, forest cover, N availability in soil, soil pH). ‘These point to a gradual change of values (from southern to northern latitudes) that impact the signals of environment and food choice (Goude and Fontugne 2016), thereby suggesting that in France, Middle Neolithic human groups have a significant intake of animal protein from terrestrial ecosystems, but also highlighting intra- and inter-group variability. Isotopic profiles from several individuals, mainly located in the western part of the French Mediterranean, have aligned more toward agriculture with minimal animal protein consumption (Herrscher and Le Bras-Goude 2010; Le Bras-Goude et al. 2009). High animal protein intake was commonly recorded in central (Goude et al. 2013) and northern France (Rey et al. 2017). Although no ichthyological remains were found, aquatic resources are an isotopically detectable part of human diet during the Middle Neolithic, but high freshwater protein diets have only been detected in a few individuals, and this is still in dispute (Rey et al. 2017). As demonstrated in other European regions, marine resources appear neglected at the beginning of the Neolithic (Richards and Schulting 2003; Salazar-García et al. 2018). However, recent data from Southern France re-evaluated such hypotheses; stable isotope data on a few individuals support the consumption of marine protein (Provost et al. 2017), and are compatible with previous work performed in the region on shells and fish remains (e.g. Cade 1998; Desse-Berset and Desse 1999). In other Western European regions, and unlike the Early Neolithic, the Middle Neolithic shows a wider variety of subsistence patterns (e.g. Salazar-García et al. 2016). In northern France at the sites of Gurgy and Pontcharaud (Fig. 1), it has been argued that stable isotope variation between males and females shows food specificities and/or of different geographic origin (e.g. wider range of resources exploited by female) (Goude et al. 2013; Rey et al. 2017). In southern France, in addition to carbon and nitrogen data, preliminary strontium isotope analysis (87Sr/86Sr) supports the hypothesis of different mobility patterns (Goude et al. 2012). These results can be linked to an economic system (i.e. more mobile pastoralists in the Garonne area versus less mobile agriculturalists in the Languedoc area) in agreement with archaeological (e.g. presence of milling material) and burial (domestic versus funerary) observations (Loison and Schmitt 2009; Tchérémissinoff et al. 2005). The quantity and preservation of human remains allows researchers to study the biological and social effects of Middle Neolithic agropastoralism intensification. In particular, the question of variation in protein intake between groups and within groups suggests a link between access to local resources and mobility/origin of individuals.

The Archaeological Site of Le Vigneau 2

The necropolis site of Le Vigneau 2 (Pussigny, department of Indre-et-Loire, Centre Val de Loire region; Fig. 1), excavated in 2013, was an opportunity to investigate human diet and mobility owing to the location (area not previously studied with biochemical methods) and biological and economic records available. The site is established on a White Tuffeau substrate, a micaceous Turonian chalk commonly used for local construction, ca. 4 km from the current path of the La Vienne stream. Several features associated with funeral activities were discovered during a development-led archaeology campaign along the new TGV line Tours–Bordeaux. These features are located on a south-western slope of a dry valley, near a portal tomb on the valley floor. The earliest phase of the site consist of 102 graves dated to the Middle Neolithic (4720–4350 cal BC), and include a dog’s burial. They belong to the Chambon culture according to the associated goods, especially the pottery, and provide direct dates from human bone collagen 14C (Coutelas et al. 2015). Ninety-two graves contained a single individual, and ten others contained two individuals. The graves were clustered in three groups probably reflecting socio-economical aspects rather than a geographical distribution: (a) a sophisticated internal arrangement such as a cist or wooden frame, corresponding to the ‘richest’ with most of the grave goods, (b) an average ‘family’ graveyard, and (c) simple pits with graves of children and females in a pit without any grave goods. Ovis remains were also present as funeral offerings, with up to three bones per an individual grave. This Middle Neolithic graveyard was interpreted as a cemetery of shepherds, buried with their domestic animals, lithic tools for butchering and skinning activities, arrowheads for hunting, and some ceramics for more domestic purposes (Coutelas et al. 2015).

To reconstruct subsistence strategies and provenance from the Middle Neolithic population of Le Vigneau 2, we carried out a multi-proxy study: bone collagen carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and sulphur (S) stable isotope ratio analysis, palaeoparasitological study, microremains from dental calculus study, aDNA tests, and teeth enamel Sr isotope ratio analysis. This represents the first time that all of these different approaches are carried out together, which considerably strengthening our knowledge of first farmers’ dietary behaviour, while building life histories of individuals, particularly of male versus females. The potential of such multi-proxy comparison for future investigations in the region will also be evaluated.

Bioarchaeological Materials and Methods

Anthropological and Archaeozoological Remains

The Le Vigneau 2 archaeological necropolis yielded 102 tombs with 112 individuals including adults and juveniles. Osteological and funerary feature descriptions were performed in situ during the excavation, but a few traits were only identified during laboratory work (details on individuals sampled for this study can be checked at supp. Mat. 1). When possible, we performed sex diagnosis of coxal bone by using morphometric and probabilistic methods (Bruzek 2002; Murail et al. 2005). Among the 68 adults excavated in the necropolis, 26 had preserved coxal bones and were found to be 14 females and seven males. Adults’ age was estimated from coxal bones too (Schmitt 2005), and juveniles’ age was estimated from both tooth growth pattern (Moorrees et al. 1963) and bone maturation (Scheuer and Black 2000). Sixty-eight adults and 37 juveniles were identified, but the collection had no individuals from 15 to 19 years, and three aged less than 1 year. Other biological features were also identified, such as teeth non-metric traits (Scott and Turner 1997). Forty percent of the individuals present shovel shape incisors, found in five double burials that could be argued to belong to family groups. Calculus deposits and dental caries were identified on several individuals (Dobney and Brothwell 1987; S. W. Hillson 2001), but in general the impact of these pathologies on the human group from Le Vigneau 2 was low. Animal remains were only found in a specific context, i.e. they are buried alone (dogs) or associated with the deceased, even in the same content. Only a few species were identified, mainly sheep including new-born specimens (Barone 1999). The lambs are mainly found as funerary deposit in female tombs (one of them even had three contemporary offerings), but the low ratio of human gender determination does not allow us to associate all fauna species with human gender. Additionally, one dog was buried individually; a burial of a child had a young squid buried with it, and wild animal remains were only identified as grave goods: two perforated pendants in a split canine of a boar, a complete one, and a bear tooth (Coutelas et al. 2015). Absence of consumed animals makes it difficult to interpret the economic and dietary information usually discussed from archaeological faunal remains.

Stable Isotope Ratios from Bone Collagen

Bone collagen is a protein in which the chemical composition originates mainly from dietary protein (e.g. Ambrose and Norr 1993); therefore, its analysis will give information on protein consumption. It is also important to take into consideration when interpreting collagen data that bone remodeling during the life of the individual, involving phases of bone resorption and bone formation, and regulated by hormonal and local factors, can influence the resulting values (Hill and Orth 1998). Bone-remodeling velocity is dependent on sex, age, and genetic characteristics (Han et al. 1997). The remodeling of growing sub-adults is faster than that of adults (Valentin 2003), implying that chemical components of food and environments are registered faster in younger individuals, and that bone composition reflects a shorter time span for juveniles than for adults (ca. 15–20 years for adults) (Hedges et al. 2007).

Carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios (δ13C, δ15N) have been used widely in studying the Neolithic (e.g. Salazar-García et al. 2018). In bone collagen, carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios help to detect the environment from which food resources are coming (e.g. terrestrial versus aquatic) and the proportion of animal protein in the individual diet (e.g. DeNiro and Epstein 1978; van der Merwe 1982; Schoeninger and DeNiro 1984; Bocherens and Drucker 2003). The interpretation of aquatic resource consumption should be made with caution if stable isotope values are not clearly from a marine source, as fish from estuarine or brackish waters can have lower nitrogen isotopic values than expected (Salazar-García et al. 2014). Applied to different past human communities, this method has allowed researchers to track the Neolithisation dietary transformation (e.g. Richards and Schulting 2003), to differentiate female and male dietary practices (Ambrose et al. 2003), or to detect specific social status (Prowse et al. 2005). More recently, sulphur isotope analysis (δ34S) was recognized as another useful tool in complementing carbon and nitrogen (Nehlich 2015), particularly to document the provenience of individuals (Richards et al. 2001; Vika 2009) and the potential consumption of marine or freshwater resources (Nehlich et al. 2010). The combination of these three isotopic ratios in bone collagen has shown its relevance to study the potential access to freshwater resources (Drucker et al. 2016), as well as cultural behaviors (de Becdelievre et al. 2015; Nehlich et al. 2011).

The preservation of osteological material at Le Vigneau 2 site allowed sampling of 40 humans (11 females, six males, 13 non-sexed adults, and six juveniles > 4 years old) and remains from 12 animals (ten lambs, one adult sheep, and one dog) for carbon and nitrogen isotope ratio analysis. From this initial corpus, 34 humans and 12 animal remains successfully provided enough collagen to get sulphur isotope ratios (cf. suppl. Mat. 1). Collagen was extracted according to a combination of Longin (1971), Bocherens (1992) and Richards and Hedges (1999) methodologies at the UMR 7269 LAMPEA laboratory in Aix-en-Provence (France). After demineralization of bone in HCl (0.5 M, 5 °C), samples are rinsed in H2Od and soaked in NaOH (20 h, room temperature). Collagen pieces are then rinsed in H2Od and solubilized in weak acid (HCl pH 2; 48H, 70 °C). Solubilized collagen is then filtered with an EzeerFilter® device, and the filtered residue is frozen (−65 °C, a few hours) and freeze-dried. Between 0.90 and 1.10 mg of freeze-dried collagen is loaded separately into aluminum tin capsules for carbon and nitrogen, and ca. 10 mg for sulphur (plus vanadium pentoxide catalyst). Elemental composition and stable isotope ratios are analyzed by EA-IRMS (Europa scientific elemental analyzer) and 20–20 IRMS (Iso-Analytical Ltd. Crewe, UK). Laboratory standards used are calibrated against the IAEA international standard for all measurements; measurement error is 0.1‰ for carbon and nitrogen and 0.2‰ for sulphur.

Strontium Isotope Ratios from Teeth Enamel

Strontium isotopic ratio (87Sr/86Sr) analysis of skeletal material is a common method for detecting provenance and mobility among past humans (e.g. Strauss et al. 2015; Sarasketa-Gartzia et al. 2018; Villalba-Mouco et al. 2018). Since radiogenic isotope 87Sr forms by radioactive decay from rubidium (87Rb), the 87Sr/86Sr signature of a specific location is determined by the underlying bedrock age and its Rb content. Older geological formations such as granite rocks have higher 87Sr/86Sr values than younger geological formations such as volcanic rock. Strontium enters ecosystems and mammal tissues without fractionation (Faure and Powell 1972; Graustein 1989), being a specific geological strontium signature incorporated into body hard tissues by substituting calcium (Ericson 1985). The strontium is ultimately derived from the Sr of the bedrock, soils, and water where individuals were living when the teeth were formed, as they have incorporated the Sr mainly through food but also water (Bentley 2006).

Among skeletal tissues, tooth enamel is the preferred substrate, since it is resistant to diagenesis from the burial environment (Budd et al. 2000; Hoppe et al. 2003). Enamel is highly mineralized (96%), mainly composed of apatite, and has no turnover during life (Nanci 2013). Therefore, tooth enamel stores information from its formation during childhood (Humphrey et al. 2008). This means that it is potentially possible to identify various changes occurring during infancy and childhood such as birth, breastfeeding, weaning, provenance, and territorial mobility (e.g. Humphrey et al. 2008). Specifically, in the case of provenance and territorial mobility it is useful to compare teeth from a single individual that reflect different moments of its life. For example, by comparing a P2/M2 with an M3, it is possible to detect differences in 87Sr/86Sr if the individual lived during childhood (P2/M2) in a geological substrate different to that in which it lived during early adulthood (M3). Furthermore, the analysis of the 87Sr/86Sr ratio in tooth enamel from a large number of individuals from one population can tag possible non-locals. However, and ideally, in order to retrieve more detailed information on territorial mobility, bioavailable Sr mapping is necessary (Price et al. 2002; Evans et al. 2010). Unfortunately, the prohibitive cost of this type of analysis makes it difficult to carry out local detailed bioavailable Sr mapping.

From Le Vigneau 2, we selected 31 individuals (ten females, six males, 14 non-sexed adults and one individual aged between 10 and 14 years old) for Sr isotope ratio analysis on enamel. We made sure that we sampled two teeth per individual: one that mineralized during an early stage of life (P2 or M2; childhood) and one that mineralized later during early adulthood (M3). We defined tooth crown age formation using the London atlas of human tooth development, specifically the median data published with the beginning of the crown starting at Coc (cups outline complete) and the end of the crown finishing at Crc (crown completed) (S. J. AlQahtani et al. 2010): P4 crown growing between 3.5 and 7.5 years old, and M2 crown growing between 4.5 and 8 years old. The M3 growth pattern is variable (e.g. Engstrom et al. 1983; Liversidge 2008; Tuteja et al. 2012); here we consider that, generally but not exclusively, the crown grows between 8.5 and 17.5 years of age, even though eruption can appear in later adulthood stages or not happen at all (cf. supplementary material 2).

Sample preparation and analysis was carried out directly in dedicated facilities at the Department of Geology of the University of Cape Town (South Africa), as described herein. Enamel samples were taken longitudinally to average the time formation of the entire dental piece. Prior to analysis, enamel surfaces were cleaned by abrasion, rinsed, and ultrasonicated for 20 min in MilliQ water. Diamond drill bits were cleaned with ethanol and ultrasonicated in MilliQ water between samples to avoid cross-contamination (Budd et al. 2000). After this, ca. 20 mg of cleaned enamel sample was digested with 2 mL of distilled 65% HNO3 in a closed Teflon beaker placed on a hotplate at 140 °C for an hour. Digested samples were then dried and dissolved again in 1.5 ml of 2 M distilled HNO3. These redissolved samples were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 20 min, and the resulting supernatant was later used for strontium solution separation chemistry. A separate fraction for each sample was used to calculate the Sr concentration; 88Sr intensity (V) regression equation was built with the SRM987 standard from the NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, USA).

Strontium atoms were isolated with 200 μl of Eichrom Sr Spec resin loaded in 2 ml Bio-Spin Disposable Chromatography Bio-Rad Columns following the method described in Pin et al. (1994). The separated strontium fraction for each sample was dried down, dissolved in 2 ml 0.2% distilled HNO3, and diluted to 200 ppb for isotope analysis. 87Sr/86Sr ratios were measured using a NuPlasma HR multicollector inductively-coupled-plasma mass spectrometer (MC-ICP-MS). Sample analyses were referenced to bracketing analyses of SRM987, using a 87Sr/86Sr reference value of 0.710255 from the NIST. All strontium isotope data are corrected for isobaric rubidium interference at 87 amu using the measured signal for 85Rb and the natural 85Rb/87Rb ratio. Instrumental mass fractionation was corrected using the measured 86Sr/88Sr ratio, the exponential law, and a true 86Sr/88Sr value of 0.1194. Results for repeated analyses of an in-house carbonate standard processed and measured with the batches of samples in this study (87Sr/86Sr = 0.708936; 2 sigma 0.000041; n = 33) are in agreement with long-term results for this in-house standard (87Sr/86Sr; 0.708915; 2 sigma 0.000047; n = 125).

Dental Calculus Microremains

Dental calculus — oral plaque that has been hardened by salivary calcium phosphate — is an increasingly important material used for several techniques in the fields of prehistory and archaeology. Dental calculus is predominantly composed of mineralized plaque biofilm. This material has been shown to contain environmental and dietary remains such as starch grains, phytoliths, lipids, proteins, and DNA from plant and animal foods. Once environmental and dietary remains have been detected, in many cases they can be identified molecularly or morphologically to the plant or animal taxa (family, genus, and sometimes species) that produced them (e.g. Armitage 1975; Henry and Piperno 2008; Warinner et al. 2014; Power et al. 2015a). As dental calculus is a stable context that is believed to be sealed from taphonomy, environmental and dietary remains are believed to be relatively isolated from taphonomic processes. Dental calculus allows a unique insight into diet, including foods underrepresented by conventional approaches and also other types of materials that leave the mouth after being masticated (Power et al. 2015b).

For this study, 11 samples of dental calculus were taken (sup. Mat. 3) and then later processed at the Plant Foods in Hominin Dietary Ecology laboratory in the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. After weighing, we added 25 μl of 10% hydrochloric acid to the calculus samples for 0.5 to 3 h. The samples were then centrifuged at 1691×g (Heraeus MEGAFUGE 16 with a microcentrifuge rotor) for 10 min, and then about 100 μl of supernatant was decanted and replaced with distilled water. This was repeated three times to remove the hydrochloric acid. After the second decanting, they were refilled with a 25% glycerine solution. We examined each slide under brightfield and cross-polarized light on a Zeiss Axioscope microscope at 400× magnification. To address the possibility of contamination, processing was done in a lab subject to a weekly regime of laboratory cleaning in addition to sediment and blank slide testing (see more specifically Power et al. 2015b, Power et al. 2016).

Palaeoparasitology

Standard palaeoparasitological analyses were conducted to retrieve eggs of gastrointestinal parasites, with the aim of accessing the health status of the population, and providing data on the lifestyle (e.g. diet, hygiene) of the individuals. Ten sediment samples taken from under the pelvis of the skeletons were prepared following the three-step RHM protocol (Rehydration-Homogenization-Microsieving), as recommended in Dufour and Le Bailly (2013). Sample analyses were performed using light microscopy (Olympus BX-51) with magnifications between ×100 and ×600 (UMR 6249 Chrono-environnement, France).

Ancient DNA

Ancient DNA analysis was performed in order to assess maternal (mitochondrial DNA) vs. paternal (Y chromosome) lineages, aiming to reconstruct matrilocal or patrilocal systems. Ancient DNA analyses were not anticipated before the excavation, so Le Vigneau 2 individuals were not excavated with aDNA precautionary care. Since petrous bones were targeted to obtain maximal aDNA recovery, only three individuals delivering enough preserved petrous bone were submitted to palaeogenetic analyses (cf. supplementary material 1). The petrous bones sampled were systematically decontaminated, i.e. scraped, cleaned with bleach, and subsequently exposed to UV radiation for 20 min on each side. All established aDNA guidelines were then followed to minimize contamination during all subsequent steps of analyses conducted in the aDNA facilities of the UMR PACEA (Bordeaux University). Fine-textured powder was collected from the inner part of the petrous bone by grinding it with an engraving cutter burr attached to a Dremel® drill. Powder was decontaminated through bleach incubation (15 min incubation with rotation at room temperature in 1 ml of 0.5% sodium hypochlorite solution) and then washed 3 times with 1 ml water to remove residual bleach. Powder was then incubated overnight in lysis buffer (0.5 M EDTA, pH 8, 25 mg/ml proteinase K, and 0.5% N-Lauryl sarkosyl). The procedure of Allentoft et al. 2015, which uses the MinElute kit from Qiagen, was then followed to extract the DNA. A combination of 18 mitochondrial and 10 Y chromosome SNPs, permitting the characterization of major maternal and paternal lineages known in European populations, were typed through one multiplex using MALDI-TOF MS-based SNP genotyping (iPLEXTM Gold technology, Sequenom, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). All primers used for these experiments and procedure details are available in Rivollat et al. (2015). The mitochondrial first hypervariable region (HVR-I, nps 16,024–16,380) was targeted using four overlapping fragments (HVR-Ia/b/c/d), following the procedures described in Rivollat et al. (2015), to determine the maternal haplotypes of the individuals. Samples were assigned to mitochondrial haplogroups and haplotypes using the combined information of HVR-I and coding region variation, following the phylogenetic classification updated by van Oven and Kayser (2009) (PhyloTree Build 17; http://www.phylotree.org).

Results and Discussions

Diet

Ancient diet was assessed in this study by comparing results from stable isotope, calculus, and palaeoparasitological analysis. These different methodologies have the advantage of exploiting various bioarchaeological materials (bone, teeth calculus, burial sediment) to increase the probability (i) of detecting food behaviour signals, and (ii) of providing evidence of a wide range of food sources. All 52 bone collagen samples provide both elemental composition and C:N elemental quality control ratios compatible with the range we are using (DeNiro 1985; van Klinken 1999) (supp. Mat. 1). Faunal carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios are normally used to establish a reference baseline for the local environment and chronological period (e.g. Goude and Fontugne 2016). In the case of Le Vigneau 2, several fauna species were found in the burials (young sheep dominating the assemblage), some of which appear symbolically deposited and therefore challenging the interpretation of human data. The isotopic data of the newborn lambs (δ13C: −22.8 to −21.5‰; δ15N: 7.1 to 7.3‰; n = 4) are consistent with the adult sheep individual (18 months; δ13C: −21.4‰; δ15N: 6.7‰). Both carbon and nitrogen values of these domestic specimens are consistent with herbivore data commonly recorded in northern France for C3 terrestrial environments (Goude and Fontugne 2016). The range of values of the other lambs (3 and 9 months) is wider (δ13C: −23.4 to −21.4‰; δ15N: 4.7 to 7.4‰; n = 6). For these age categories, we would have expected higher nitrogen ratios due to milk consumption (Balasse et al. 1997), or at least similar values (already weaned) to those of adult and neonates. However, part of the animals of these age categories show lower nitrogen values (Fig. 2). To investigate this observation, a specific zooarchaeological study would help (see e.g. Balasse et al. 2002; Balasse 2003). In any case, for this human-focused study we will simply argue that this group of fauna is potentially from weaned specimens that might have consumed plants/fodder with low δ15N values, such as legumes such as lucerne, clover, vetch. or lupine (Virginia and Delwiche 1982). The case of the dog (lower δ15N than the human group) indicates similarities with several Middle Neolithic sites, and could reflect a consumption of human refuse with less animal protein than human food (Goude and Fontugne 2016).

Human data highlights limited isotopic variability independent of the sex, age, or other biological (tooth wear, calculus presence) and archaeological (ornaments, presence of shell) criteria: δ13C: −21.2 to −20.1‰; δ15N: 9.1 to 11.9‰; n = 40 (supp. Mat. 1). These isotope values show that humans based their diet on terrestrial resources. Except for a juvenile individual, the rest of the human group also shows a higher trophic position than that of the fauna studied (Δ13C: 1.8‰; Δ15N: 3.1‰), indicating a significant consumption of animal protein (Fig. 2). These results agree with preliminary observations proposed by the zooarchaeological study, highlighting an economy turned toward pastoralism and sheep herding instead of agriculture.

An immature individual (LV H28), aged ca. 6 years old, shows a higher δ15N (+1.9‰) compared with the rest of the human group. In general, the juvenile groups of 3–5 and 6–9 years old show a range of data slightly wider (Δ13C: 1.1‰; Δ15N: 2.5‰; n = 6) than the adolescents and adults. The biological characteristics of these age categories, such as their generally low body mass index (egg. Rolland-Cachera et al. 1991; Cole et al. 2000; Martinson et al. 2015), could be one of the explanations for the variability observed, knowing that growth and physiological factors can have an impact on protein synthesis (e.g. de Luca et al. 2012). The bone and skull remains of the immature LV H28 were not well-preserved enough to provide health status data, so physiological/pathological hypothesis can be suspected but not supported by any evidence. Another explanation for these values, from the dietary point of view, could be that the immature consumed resources with high δ15N, such as meat of other terrestrial animals not consumed by the rest of the population (e.g. pig, commonly recorded in other northern Neolithic sites) and/or freshwater fish. None of these resources was found on the site during the excavation, but it should be kept in mind that the funerary context may misrepresent the economical practices from the population buried at the funerary site.

The eleven samples of calculus analyzed produced a variety of microremains including starches, phytoliths, calcium oxalate, and fungal and invertebrate remains. The remains derive from Triticeae seed, an unidentified non-Triticeae starchy plant, a form of leafy vegetable, fungi, mites, micro-charcoal, and various other non-dietary particles. As this technique is an emerging method, there is no Neolithic population to compare results with; however, the samples suggest a relatively homogenous diet. If assemblages are compared with reference populations from other earlier European foraging populations (Henry 2010; Power et al. 2016), Le Vigneau 2 shows on average a higher intensity in plant foods than Chalcolithic calculus per mg (Fig. 3; Power et al. 2014) but lower than Magdalenian samples (Henry et al. 2014; Power et al. 2015a). In terms of diversity, Le Vigneau 2 has the least diversity, although the small sample size must be kept in mind (Fig. 3). The relative homogeneity observed in Le Vigneau 2 samples is consistent with a consumption pattern focused on few species, probably associated to agricultural practices, although wild species probably were consumed too. Palaeoparasitological microscopy did not allow the detection of parasite eggs. The abundance of mineral particles and the absence of organic matter in the prepared samples suggests taphonomic processes are responsible for the lack of results.

Le Vigneau 2 total numbers of plant microremains (top) and minimum botanical unit per mg (bottom) with previously published comparison data from Magdalenian, Gravettian, and Chalcolithic populations. Minimum botanical unit is measure of the lowest number plant taxa or parts represented (Power et al. 2018). Magdalenian = Abri Pataud, La Madeleine and El Mirón (Henry et al. 2014; Power et al. 2015a), Gravettian = Předmostí, Dolní Věstonice and Pavlov (Henry 2010; Power et al. 2016), Chalcolithic = Camino del Molino (Power et al. 2014)

Mobility and Provenance

In order to assess both provenance and territorial mobility from these populations, we coupled sulphur stable isotope with strontium isotope analysis. The first gives information on geography and proximity to the coastline, while the second give information about the association of humans to specific geologies and can help discern locals from non-locals. We also carried out aDNA analysis to get information on ancestry from the individuals studied.

We assessed S isotopic values from 46 collagen samples. Of them, 41 exhibited good preservation indicators (%S, C:S, N:S) (Nehlich and Richards 2009); the remaining five (two animals and three humans) are excluded from the interpretation (supplementary material 1). Animal sulphur isotope values vary by age (Fig. 2b): adult sheep, dog, and two lambs of 3 months show the lowest values (from 9.4 to 11.5‰), while the rest of the lambs show values ranging from 12.5 to 15.2‰. Moreover, there is a significant correlation (p < 0.05; Pearson correlation; Statistica 9.1 ®) between δ34S and δ15N for all ovis samples; the animals with lowest nitrogen values also show the lowest sulphur isotopic ratios, which could be related to different breeding/feeding areas, and is perhaps explained by animal trade.

For humans, the sulphur isotope ratios range from 8.0 to 14.9‰, with slight distribution variations according to sex and age, but with no significant statistical difference. Most of the human values fall within the onsite fauna range. When this data set is compared with published data from Mesolithic sites and modern food samples (only data available) from elsewhere in France (Camin et al. 2007; Schellenberg et al. 2010; Drucker et al. 2016), we observe higher ratios than what was known up to now in this inland context (Fig. 2b). The local geology (http://infoterre.brgm.fr/viewer/MainTileForward.do#) does not provide any clue as to why the existence of this high δ34S is recorded in most of the archaeological samples. High δ34S ratios can be found in geological contexts rich in gypsum or barite (O. Nehlich 2009), or in coastal environments. The Le Vigneau 2 site is located ca. 192 km from the Atlantic coast, ca. 150 km away from main gypsum deposits of the Paris basin, and ca. 90 km away from the closest barite deposit still exploited today (Chaillac). The presence of nearby agricultural lands and the potential use of modern chemical fertilizers could be an argument for local sulphur pollution in soils. However, neither %S, C:S nor N:S ratios (still in the range of accepted values) are statistically correlated together, nor the δ34S to the burial depth (supplementary materials 1). In such a context, the interpretation of archaeological sulphur isotope ratios must be cautious. Both animal and human present important δ34S variability, reflecting either a wide local range of δ34S in soils or a significant trading network of this group across different territories with different sulphur isotopic compositions.

Strontium isotope ratios were obtained from 61 teeth from 31 individuals, and range from 0.708 to 0.714 (supplementary materials 2). The 87Sr/86Sr database of continental France (Willmes et al. 2014) was used to assess bioavailable Sr from the region. The spots in it measured (n = 3; 20 to 27 km away from the Le Vigneau 2 site) indicate variability among plant samples (from 0.708 to 0.714; http://80.69.77.150/), with no specific spatial gradient. These plant values are similar to the archaeological human ratios from this study. This high variability in the broader region, together with the lack of a specific mapping of the immediate surrounding of the site, makes it difficult to define territorial mobility. However, provenance can be approached by analyzing the data from the actual population analyzed by comparing M2 values from all individuals, and individual life histories can be approached by individually comparing M2 values to M3 values. Overall, the variation observed (at both inter- and intra-individual levels) is not homogeneous, and could be the result of different behaviors, provenance, or territorial mobility.

In the human group, the M3 mean ± 2 sd of the 87Sr/86Sr is of 0.7098 ± 0.0029, and the M2/P4 mean ± 2 sd of the 87Sr/86Sr is of 0.7101 ± 0.0037. The two are similar, and would define the local range where most of the population lived. At an intra-individual level, the difference of 87Sr/86Sr between early adulthood (M3) and childhood (M2/P4) is small (≤ 0.001; n = 6) for males, and small as well but wider for females (Δ87Sr/86Sr from |0.000| to |0.004|; n = 10) when compared to the rest of the group (supplementary materials 2; Fig. 4). A noteworthy pattern observed is that in the case of the males, M3 values are always higher than M2/P4 values, while for females M3 values are most of the time lower than the M2/P4 values (Fig. 4), suggesting perhaps a pattern in which males and females came from different areas or consumed different resources from the overall region. In any case, the Sr variation recorded between early adulthood and childhood is not statistically significant when comparing male/female/unsexed individuals (p > 0.05; non-parametric U Mann–Whitney test, Statistica 9.1 ®). As a curiosity, the site delivered several double burials with individuals showing shovel shape incisors and thus a potential family group. One of the double burials has Sr data available for both individuals (H11 and H12; Fig. 4), showing that both could have spent childhood and early adulthood in the same environment, potentially away from the site.

With regard to aDNA analysis and the information this reveals on genetic provenance, Table 1 presents the mitochondrial haplogroups (SNPs typing) retrieved from the human remains. SNPs typing made it possible to assign one individual (LVH3, male < 60 years old) to maternal lineage K (or derivatives), and another individual (LVH12) to lineage H (or derivatives), whereas the low number of SNPs recovered for the last sample (LVH26) did not make it possible to assign any haplogroup. No Y chromosome SNP, as well as no reproducible result for HVR-I sequences, could be obtained for any Le Vigneau 2 individual. Unfortunately, major DNA degradation prevents precise identification of the maternal and paternal lineages, and these two mitochondrial haplogroups do not allow any assessment about female mobility. However, we can note that maternal lineages characterized in the Le Vigneau 2 site are quite common in Neolithic farmer groups and fit within the French Middle Neolithic variability (from 14 to 25.5% for haplogroup K and from 7.9 to 40.9% for haplogroup H; Beau et al. 2017), including farmers from the Paris Basin (35% of H and 18.33% of K for the Gurgy site; Rivollat et al. 2015).

Human Behaviors

The data obtained about animal consumption (carbon and nitrogen isotope ratio, the record of animal remains) and the plant foods (calculus microremains) indicate an homogenous specialized diet. The collagen isotope ratios and the low variability of plant species identified indicate a diet dominated by animal resources, along with an economy centred on pastoralism rather than agriculture. The ritual deposition of lambs in female tombs strengthens this hypothesis. The fact that no female–male differences have been reported could be linked to the targeted activities on sheep breeding and exploitation of secondary products such as wool (Coutelas et al. 2015). If sheep constitute the main economic resource, males and females (even if performing differentiated activities, which is unknown) have access to the same animal products, in line with a less gender-based variability. In the absence of archaeological data on dwelling sites, our discussion was based on partial funerary observations and bioarchaeological analyses.

It is difficult to compare the whole dataset to other Middle Neolithic populations, as no previous study has combined these techniques. Despite this, the available stable isotope database (CN) on animal and human bone collagen from the centre and the north of France (Goude et al. 2015; Goude et al. 2013; Rey et al. 2017) allows partial regional comparison of dietary practices. Despite being near aquatic resources, the people of Le Vigneau 2 differ from other French and Iberian Middle Neolithic populations in that they did not exploit aquatic foods (Goude et al. 2013; Rey et al. 2017; Salazar-García et al. 2016) (Fig. 5). The immature outlier’s values we found are probably more related to physiological phenomena than a specific diet; this period of child growth is poorly documented in stable isotope studies, even though medical literature warns about skeletal growth heterogeneity until pubertal age (Szulc et al. 2000). Compared to other regional sites (Fig. 5), Le Vigneau 2 sites are differentiated by (1) the low variability of carbon and nitrogen data and the absence of gender-based difference, and (2) the low diversity of animal species potentially exploited. However, gender-based differences in stable isotope data on other Neolithic sites from the region do exist, as is the case at the Gurgy and Pontcharaud sites, and could indicate either different access to food resources (in terms of species preferentially exploited) and/or different mobility patterns (inferred from consumption of resources from different ecosystems and isotopic variability). On Gurgy and Pontcharaud funerary sites, several animal species were found (mainly pig, cattle, sheep, and goat), but sheep are not considered as the dominant resource in these areas, as mentioned by regional archaeozoological data (Bréhard 2011) and stable isotope analysis (Goude et al. 2013; Rey et al. 2017).

Comparison of Le Vigneau 2 carbon and nitrogen ratios with those from other Middle Neolithic and Late Neolithic sites in Northern France (from Goude et al. 2013; Goude et al. 2015; Rey et al. 2017). Dotted line represents hypothetical delineation between individuals consuming mainly terrestrial resources (below), with various amount of animal protein intake and individuals including other resources (above) such as freshwater fish/young animal proteins in diet

Discussion about territorial mobility patterns also suffers from the lack of studies and regional databases (Willmes et al. 2014). Previous works using Sr isotope analysis in southern French Middle Neolithic individuals from five sites (Goude et al. 2012) have highlighted a potential greater mobility for pastoralists than for agriculturalists. Furthermore, at the Middle Neolithic site of Pontcharaud, a patrilocal society in which adolescent females came from abroad into the study groups has been suggested, based on significant isotopic variability (CN) recorded in female bone collagen (Goude et al. 2013). Sr data from neighboring regions in Central Europe support the presence of patrilocal systems from the beginning of the Neolithic, as males indicate lower Sr variability compared to females (Bentley et al. 2012). As we have seen, this is not clear for the Le Vigneau 2 population, neither for carbon and nitrogen nor for strontium isotope data, which shows there is no strong trace of this purported patrilocal social structure in the Middle Neolithic of northern France. However, female Sr variability (0.71018 ± 0.00171; Δ = 0.00591; n = 20) is greater than what was observed in Early Neolithic Alsatian sites, and agrees with the European patrilocal pattern proposed by authors (Bentley et al. 2012). Ethnographic evidence frequently shows that female exogamy is a common trait (e.g. Murdock 1967; Wrangham 1987), and publications refer to this pattern to highlight the role of female mobility for trade (Brown 2016). However, we should not simply blindly project ethnographic evidence into a deep prehistoric past that might have well had very different social structures and mind-sets to those we have recorded in living communities.

Conclusions and Perspectives

Recent years have seen significant expansion of archaeological science specialization. This broadening field is now targeting many facets of the lives of ancient people. Continuing a data-rich trajectory is important for advancing our knowledge about human societies. However, with the growing specialization available in archaeological science, there is a danger that large amounts of data are created that fail to solve the biggest questions about ancient human societies, due to the lack of optimally multidisciplinary research. It may not at a later stage always be possible to address uneven application of multiple disciplinarity. We show in this study how different techniques can be applied to target a singular research question. The goal of identifying intra-population variability in diet and mobility variation is still an elusive challenge in Neolithic archaeology, and we hope that our study provides a dataset that helps researchers appropriately address this challenge.

Conducting this specific multi-proxy study allowed us to identify different types of foods consumed by Neolithic human groups. Stable isotope data, archaeological artifacts, and anthropological and zooarchaeological information together support the hypothesis of an economy mainly focused on pastoralism, with no visible gender-related difference in terms of food consumption. Dental calculus analysis revealed the exploitation of wild plants, not observed before in Neolithic anthropological studies. The comparison with archaeological hunter–gatherer groups also made it possible to document the variability of plant species exploited, potentially reduced for these agropastoralists in comparison. We observe no food differences between males and females, and our isotopic provenance study suggests no strong trace of a patrilocal social structure, thus the use of the territory by this population is not clearly linked to gender. As a next step, the individuals from Le Vigneau 2 will be studied through dental wear to document whether specific economic activities were carried out (e.g. wool, fibre processing) and if males and females had comparable behaviors.

Our ambitious multi-proxy study encountered limitations, particularly for sensitive bioarchaeological material (mainly aDNA, parasite eggs), but further investigations can be considered in the future, such as to test the presence of the human pathogenic amoeba (Entamoeba histolytica) in the samples; palaeogenetics could also be performed to test the presence of other type of parasite markers (Côté et al. 2016; Le Bailly and Araujo 2016). We propose that S isotope data may also be able to corroborate palaeogenetic evidence of mobility, as well as providing new information on its timing. This highlights the necessity to further develop archaeological geographical databases and mapping of current soil use and modern potential contaminants. However, it seems necessary to continue such a multi-proxy approach to determine the best archaeological context for this kind of investigation.

References

Allentoft, M. E., Sikora, M., Sjögren, K. G., et al. (2015). Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia. Nature, 522, 167–172.

AlQahtani, S. J., Hector, M. P., & Liversidge, H. M. (2010). Brief communication: The London atlas of human tooth development and eruption. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 142(3), 481–490.

Ambrose, S. H., & Norr, L. (1993). Experimental evidence for the relationship of the carbon isotope ratios of whole diet and dietary protein to those of bone collagen and carbonate. In J. B. Lambert & G. Grupe (Eds.), Prehistoric human bone archaeology at the molecular level. Berlin: Springer.

Ambrose, S. H., Buikstra, J., & Krueger, H. W. (2003). Status and gender differences in diet at mound 72 Cahokia revealed by isotopic analysis of bone. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 22, 217–226.

Armitage, P. L. (1975). The extraction and identification of opal phytoliths from the teeth of ungulates. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2, 450–455.

Balasse, M. (2003). Maintenir le jeune en vie pour stimuler la production laitière ? Différences entre les bovins et les caprinés. Anthropozoologica, 37, 3–10.

Balasse, M., Bocherens, H., Tresset, A., Mariotti, A., & Vigne, J.-D. (1997). Emergence de la production laitière au Néolithique ? Contribution de l’analyse isotopique d’ossements de bovins archéologiques. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences (2a), 325(12), 1005–1010.

Balasse, M., Smith, A. B., Ambrose, S. H., & Leigh, S. R. (2002). Determining sheep birth seasonality by analysis of tooth enamel oxygen isotope ratios: The late stone age site of Kasteelberg (South Africa). Journal of Archaeological Science, 30(2), 205–215.

Barone, R. (1999). Anatomie comparée des mammifères domestiques. Tome premier, Ostéologie. Quatrième édition. Paris: Vigot frères.

Beau, A., Rivollat, M., Réveillas, H., Pemonge, M.-H., Mendisco, F., Thomas, Y., Lefranc, P., & Deguilloux, M.-F. (2017). Multi-scale ancient DNA analyses confirm the western origin of Michelsberg farmers and document probable practices of human sacrifice. PLoS One, 12(7), e0179742.

Bentley, R. A. (2006). Strontium isotopes from the earth to the archaeological skeleton: A review. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 13, 136–187.

Bentley R.A., Bickle P., Fibiger L, Nowell G. M., Dale C. W., Hedges R, Hamilton J., Wahl J., Francken M., Grupe G., Lenneis E., Teschler-Nicola M., Arbogast R.-M., Hofmann D. & Whittle A. (2012). Community differentiation and kinship among Europe’s first farmers. PNAS, 109, 9326–9330.

Bocherens, H. (1992). Biogéochimie isotopique (13C,15N,18O) et paléontologie des vertébrés : application à l’étude des réseaux trophiques révolus et des paléoenvironnements [PhD]. Paris: Université Paris VI.

Bocherens, H., & Drucker, D. (2003). Trophic level isotopic enrichment of carbon and nitrogen in bone collagen: Case studies from recent and ancient terrestrial ecosystems. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 13, 46–53.

Bocherens, H., Drucker, D. G., & Taubald, H. (2011). Preservation of bone collagen sulphur isotopic compositions in an early Holocene river-bank archaeological site. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 310, 32–38.

Bréhard, S. (2011). Le complexe chasséen vu par l’archéozoologie : révision de la dichotomie Nord–Sud et confirmation de la partition fonctionnelle au sein des sites méridionaux. Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française, 108(1), 1–20.

Brown, K. A. (2016). Women on the move. The DNA evidence for female mobility and exogamy in prehistory. In J. Leary (Ed.), Past mobilities archaeological approaches to movement and mobility (pp. 155–174). New York: Routledge.

Bruzek, J. (2002). A method for visual determination of sex, using the human hip bone. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 117, 157–168.

Budd, P., Montgomery, J., Barreiro, B., & Thomas, R. G. (2000). Differential diagenesis of strontium in archaeological human dental tissues. Applied Geochemistry, 15(5), 687–694.

Cade, C. (1998). Les coquillages marins dans les gisements préhistoriques du Midi méditerranéen français. In G. Camps (Ed.), L’homme préhistorique et la mer. Paris: Comité des Travaux historiques et scientifiques.

Camin, F., Bontempo, L., Heinrich, K., Horacek, M., Kelly, S. D., Schlicht, C., Thomas, F., Monahan, F. J., Hoogewerff, J., & Rossmann, A. (2007). Multi-element (H,C,N,S) stable isotope characteristics of lamb meat from different European regions. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 389(1), 309–320.

Cole, T., Bellizzi, M., Flegal, K., & Dietz, W. (2000). Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: International survey. BMJ, 320(7244), 1240–1243.

Côté, N., Daligault, J., Pruvost, M., Bennett, E. A., Gorge, O., Guimaraes, S., et al. (2016). A new high-throughput approach to genotype ancient human gastrointestinal parasites. PLoS One, 11(1), e0146230. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146230.

Coutelas A., Hauzeur A., Courboin-Gresillaud E., & Terrom J. (2015). Pussigny (37), « Le Vigneau 2 ». Nécropoles néolithique et protohistoriques. Rapport final d’opération. Orléans: SRA Centre. [Avec la collaboration de Chesnaux, L., Chol, E., Chrzavzez, J., Fernandès, P. Gomez de Soto, J., Goude, G., Louyot, D., Mens, E., Roux, L., Rué, M., Varennes, G.].

de Becdelievre, C., Goude, G., Jovanović, J., Herrscher, E., Le Roy, M., Rottier, S., & Stefanović, S. (2015). Prehistoric motherhood: Diet from pregnancy to baby-led weaning in the Danube gorges Mesolithic–Neolithic. Abstract. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 156(S60), 116.

de Luca, A., Boisseau, N., Tea, I., Louvet, I., Robins, R. J., Forhan, A., Charles, M. A., & Hankard, R. (2012). δ15N and δ13C in hair from newborn infants and their mothers: A cohort study. Pediatric Research, 71(5), 598–604.

DeNiro, M. J. (1985). Post-mortem preservation and alteration of in vivo bone collagen isotope ratios on relation to palaeodietary reconstruction. Nature, 317(6032), 806–809.

DeNiro, M. J., & Epstein, S. (1978). Influence of diet on the distribution of carbon isotopes in animals. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 42, 495–506.

Desse-Berset, N., & Desse, J. (1999). Les poissons. In S. Tinè (Ed.), Il Neolitico della caverna delle Arene Candide (scavi 1972–1977) (pp. 36–50). Istituto Internazionale di Studi Liguri: Bordighera.

Dobney, K., & Brothwell, D. (1987). A method for evaluating the amount of dental calculus on teeth from archaeological sites. Journal of Archaeological Science, 14(4), 343–351.

Drucker, D. G., Bridault, A., Cupillard, C., Hujic, A., & Bocherens, H. (2011). Evolution of habitat and environment of red deer (Cervus elaphus) during the Late-glacial and early Holocene in eastern France (French Jura and the western Alps) using multi-isotope analysis (δ13C, δ15N, δ18O, δ34S) of archaeological remains. Quaternary International, 245, 268–278.

Drucker, D. G., Valentin, F., Thevenet, C., Mordant, D., Cottiaux, R., Delsate, D., & Van Neer, W. (2016). Aquatic resources in human diet in the late Mesolithic in northern France and Luxembourg: Insights from carbon, nitrogen and sulphur isotope ratios. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 10, 351–368.

Dufour, B., & Le Bailly, M. (2013). Testing new parasite egg extraction methods in archaeoparasitology and an attempt at quantification. International Journal of Palaeopathology, 3, 199–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpp.2013.03.008.

Engstrom, C., Engstrom, H., & Sagne, S. (1983). Lower third molar development in relation to skeletal maturity and chronological age. The Angle Orthodontist, 53(2), 97–106.

Ericson, J. E. (1985). Strontium isotope characterization in the study of prehistoric human ecology. Journal of Human Evolution, 14(5), 503–514.

Evans, J. A., Montgomery, J., Wildman, G., & Boulton, N. (2010). Spatial variations in biosphere 87Sr/86Sr in Britain. Journal of the Geological Society, 167, 1–4.

Faure, G., & Powell, J. L. (1972). Strontium isotope geology. Berlin: Springer

Goude G. (2007). Etude des modes de subsistance de populations néolithiques (VIe-IVe millénaires av. J.-C.) dans le nord-ouest de la Méditerranée. Approche par l’utilisation des isotopes stables (δ 13 C et δ 15 N) du collagène [PhD]. Talence-Leipzig: Université Bordeaux 1-Université de Leipzig.

Goude, G., & Fontugne, M. (2016). Carbon and nitrogen isotopic variability in bone collagen during the Neolithic period: Influence of environmental factors and diet. Journal of Archaeological Science, 70, 117–131.

Goude, G., Castroni, F., Herrscher, E., Cabut, S., & Tafuri, M. A. (2012). First strontium isotopic evidence of mobility in the Neolithic of southern France. European Journal of Archaeology, 15, 421–439.

Goude, G., Schmitt, A., Herrscher, E., Loison, G., Cabut, S., & André, G. (2013). Pratiques alimentaires au Néolithique moyen : Nouvelles données sur le site de Pontcharaud 2 (Auvergne, France). Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française, 110(2), 299–317.

Goude, G., Balasescu, A., Réveillas, H., Thomas, Y., & Lefranc, P. (2015). Diet variability and stable isotope analyses: Looking for variables within the late Neolithic and Iron age human groups from Gougenheim site and surrounding areas (Alsace, France). International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 25, 988–996.

Graustein, W. C. (1989). 87Sr/86Sr ratios measure the sources and flow of strontium in terrestrial ecosystems. In P. W. Rundel, J. R. Ehleringer, & K. A. Nagy (Eds.), Stable isotopes in ecological research (pp. 491–512). New York: Springer.

Han, Z. H., Palnitkar, S., Rao, D. S., Nelson, D., & Parfitt, A. M. (1997). Effects of ethnicity and age or menopause on the remodeling and turnover of iliac bone: Implications for mechanisms of bone loss. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 12(4), 498–508.

Hedges, R. E. M., Clement, J. G., Thomas, C. D. L., & O’Connell, T. C. (2007). Collagen turnover in the adult femoral mid-shaft: Modeled from anthropogenic radiocarbon tracer measurements. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 133(2), 808–816.

Henry, A. G. (2010). Plant foods and the dietary ecology of Neandertals and modern humans [PhD]. Washington: George Washington University.

Henry, A. G., & Piperno, D. R. (2008). Using plant microfossils from dental calculus to recover human diet: A case study from Tell al-Raqā’i, Syria. Journal of Archaeological Science, 35, 1943–1950.

Henry, A. G., Brooks, A. S., & Piperno, D. R. (2014). Plant foods and the dietary ecology of Neanderthals and early modern humans. Journal of Human Evolution, 69, 44–54.

Herrscher, E., & Le Bras-Goude, G. (2010). Southern French Neolithic populations: Isotopic evidence for regional specificities in environment and diet. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 14(2), 259–272.

Hill, P. A., & Orth, M. (1998). Bone remodelling. British Journal of Orthodontics, 25, 101–107.

Hillson, S. W. (2001). Recording dental caries in archaeological human remains. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 11, 249–289.

Hoppe, K. A., Koch, P. L., & Furutani, T. T. (2003). Assessing the preservation of biogenic strontium in fossil bones and tooth enamel. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 13(1–2), 20–28.

Humphrey, L. T., Dean, M. C., Jeffries, T. E., & Penn, M. (2008). Unlocking evidence of early diet from tooth enamel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(19), 6834–6839.

Le Bailly, M., & Araujo, A. (2016). Past intestinal parasites. In paleomicrobiology of humans. American Society of Microbiology. Washington, DC: ASM Press. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.PoH-0013-2015.

Le Bras-Goude, G., Schmitt, A., & Loison, G. (2009). Comportements alimentaires, aspects biologiques et sociaux au Néolithique : le cas du Crès (Hérault, France). Comptes Rendus Palevol, 8, 79–91.

Lee-Thorp, J. (2008). On isotopes and old bones. Archaeometry, 50(6), 925–950.

Liversidge, H. M. (2008). Timing of human mandibular third molar formation. Annals of Human Biology, 35(3), 294–321.

Loison, G., & Schmitt, A. (2009). Diversité des pratiques funéraires et espaces sépulcraux sectorisés au Chasséen ancien sur le site du Crès à Béziers (Hérault). Croisements de données archéologiques et anthropologiques. Gallia Préhistoire, 51, 245–272.

Longin, R. (1971). New method of collagen extraction for radiocarbon dating. Nature, 230, 241–242.

Martinson, M. L., McLanahan, S., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2015). Variation in child body mass index patterns by race/ethnicity and maternal nativity status in the United States and England. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19(2), 373–380.

Moorrees, C. F. A., Fanning, E. A., & Hunt, E. E. (1963). Age variation of formation stages for ten permanent teeth. Journal of Dental Research, 42(6), 1490–1502.

Murail, P., Bruzek, J., Houët, F., & Cunha, E. (2005). DSP: A tool for probabilistic sex diagnosis using worldwide variability in hip-bone measurement. Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris, 3-4, 167–176.

Murdock, G. P. (1967). Ethnographic atlas. Pittsburgh: University Of Pittsburgh Press.

Nanci, A. (2013). Ten Cate’s oral histology: Development, structure and function. St Louis: Elsevier Mosby.

Nehlich, O. (2009). Sulphur isotope analysis of archaeological tissues: A new method for reconstructing past human and animal diet and mobility [PhD]. Leipzig: University of Leipzig.

Nehlich, O. (2015). The application of sulphur isotope analyses in archaeological research: A review. Earth-Science Reviews, 142, 1–17.

Nehlich, O., & Richards, M. P. (2009). Establishing collagen quality criteria for sulphur isotope analysis of archaeological bone collagen. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 1(1), 59–75.

Nehlich, O., Boric, D., Stefanovic, S., & Richards, M. P. (2010). Sulphur isotope evidence for freshwater fish consumption: A case study from the Danube Gorges, SE Europe. Journal of Archaeological Science, 37(5), 1131–1139.

Nehlich, O., Fuller, B. T., Jay, M., Mora, A., Nicholson, R. A., Smith, C. I., & Richards, M. P. (2011). Application of sulphur isotope ratios to examine weaning patterns and freshwater fish consumption in Roman Oxfordshire, UK. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 75(17), 4963–4977.

Pin, C., Briot, D., Bassin, C., & Poitrasson, F. (1994). Concomitant separation of strontium and samarium-neodymium for isotopic analysis in silicate samples, based on specific extraction chromatography. Analytica Chimica Acta, 298(2), 209–217.

Power, R. C., Salazar-García, D. C., Wittig, R. M., & Henry, A. G. (2014). Assessing use and suitability of scanning electron microscopy in the analysis of micro remains in dental calculus. Journal of Archaeological Science, 49, 160–169.

Power, R. C., Salazar-García, D. C., Straus, L. G., González Morales, M. R., & Henry, A. G. (2015a). Microremains from El Mirón cave human dental calculus suggest a mixed plant-animal subsistence economy during the Magdalenian in northern Iberia. Journal of Archaeological Science, 60, 39–46.

Power, R. C., Salazar-García, D. C., Wittig, R. M., Freiberg, M., & Henry, A. G. (2015b). Dental calculus evidence of Taï Forest chimpanzee plant consumption and life history transitions. Scientific Reports, 5, 15161. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep15161.

Power, R. C., Salazar-García, D. C., & Henry, A. G. (2016). Dental calculus evidence of Gravettian diet and behaviour at Dolní Věstonice and Pavlov. In J. Svoboda (Ed.), Dolní Věstonice II: Chronostratigraphy, paleoethnology, paleoanthropology (pp. 345–352). Brno: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Institute of Archaeology.

Power, R. C., Salazar-García, D. C., Rubini, M., Darlas, A., Harvati, K., Walker, M., Hublin, J. J., & Henry, A. G. (2018). Dental calculus indicates widespread plant use within the stable Neanderthal dietary niche. Journal of Human Evolution, 119, 27–41.

Price, T. D., Burton, J. H., & Bentley, R. A. (2002). The characterization of biologically available strontium isotope ratios for the study of prehistoric migration. Archaeometry, 44, 117–135.

Provost S., Binder D., Duday H., Goude G., Durrenmath G., & Gourichon L. (2017). Une sépulture collective à la transition des 6ème et 5ème millénaires BCE : Mougins — « Les Bréguières » 1 (Alpes-Maritimes, France), fouilles Maurice SECHTER 1966–1967. Gallia Préhistoire, 57, 269–338. [Avec la collaboration de Castex D., Delhon C., Gentile I., Vuillien M., Zemour A.]

Prowse, T., Schwarcz, H. P., Saunders, R. S., Macchiarelli, R., & Bondioli, L. (2005). Isotopic evidence for age related variation in diet from Isola Sacra. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 128, 2–13.

Rey, L., Goude, G., & Rottier, S. (2017). Comportements alimentaires au Néolithique : nouveaux résultats dans le Bassin parisien à partir de l’étude isotopique (δ13C, δ15N) de la nécropole de Gurgy « Les Noisats » (Yonne, Ve millénaire av. J.-C.). Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris, 29, 54–69.

Richards, M. P., & Hedges, R. (1999). Stable isotope evidence for similarities in the types marine food used by late Mesolithic humans at sites along the Atlantic coast of Europe. Journal of Archaeological Science, 26, 712–722.

Richards, M. P., & Schulting, R. J. (2003). Sharp shift in diet at onset of Neolithic. Nature, 425, 366.

Richards, M. P., Fuller, B. T., & Hedges, R. E. M. (2001). Sulphur isotopic variation in ancient bone collagen from Europe: Implications for human palaeodiet, residence mobility, and modern pollutant studies. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 191(3–4), 185–190.

Rivollat, M., Mendisco, F., Pemonge, M.-H., Safi, A., Saint-Marc, D., Brémond, A., Couture-Veschambre, C., Rottier, S., & Deguilloux, M.-F. (2015). When the waves of European neolithization met: first paleogenetic evidence from early farmers in the southern Paris Basin. PLoS One, 10(4), e0125521.

Rolland-Cachera, M., Cole, T., Sempé, M., Tichet, J., Rossignol, C., & Charraud, A. (1991). Body mass index variations: centiles from birth to 87 years. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 45(1), 13–21.

Salazar-García, D. C., Aura, J. E., Olària, C. R., Talamo, S., Morales, J. V., & Richards, M. P. (2014). Isotope evidence for the use of marine resources in the eastern Iberian Mesolithic. Journal of Archaeological Science, 42, 231–240.

Salazar-García, D. C., Romero, A., García-Borja, P., Subirà, E., & Richards, M. P. (2016). A combined dietary approach using isotope and dental buccal-microwear analysis of humans from the Neolithic, Roman and Medieval periods from archaeological site of Tossal de les Basses (Alicante, Spain). Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 6, 610–619.

Salazar-García, D. C., Fontanals-Coll, M., Goude, G., & Subira, E. (2018). To ‘seafood’ or not to ‘seafood’? An isotopic perspective on dietary preferences at the Mesolithic–Neolithic transition in the western Mediterranean. Quaternary International, 470, 497–510.

Sarasketa-Gartzia I., Villalba-Mouco V., le Roux P., Arrizabalaga Á., & Salazar-García DC. (2018). Late Neolithic–Chalcolithic socio-economical dynamics in Northern Iberia. A multi-isotope study on diet and provenance from Santimamiñe and Pico Ramos archaeological sites (Basque Country, Spain). Quaternary International (in press).

Schellenberg, A., Chmielus, S., Schlicht, C., Camin, F., Perini, M., Bontempo, L., Heinrich, K., Kelly, S. D., Rossmann, A., Thomas, F., et al. (2010). Multielement stable isotope ratios (H, C, N, S) of honey from different European regions. Food Chemistry, 121(3), 770–777.

Scheuer, L., & Black, S. (2000). Developmental juvenile osteology (587 p). Oxford: Elsevier Academic

Schmitt, A. (2005). Une nouvelle méthode pour estimer l’âge au décès des adultes à partir de la surface sacro-pelvienne iliaque. Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris, 17(1–2), 89–101.

Schoeninger, M. J., & DeNiro, M. J. (1984). Nitrogen and carbon isotopic composition of bone collagen from marine and terrestrial animals. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 48, 625–639.

Schoeninger, M. J., De Niro, M. J., & Tauber, H. (1983). Stable nitrogen isotope ratios of bone collagen reflect marine and terrestrial components of prehistoric human diet. Science, 220, 1381–1383.

Scott, G. R., & Turner, C. G. (1997). The anthropology of modern human teeth : dental morphology and its variation in recent human populations (Cambridge studies in biological and evolutionary anthropology). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Strauss, A., Oliveira, R. E., Bernardo, D. V., Salazar-García, D. C., Talamo, S., Jaouen, K., Hubbe, M., Black, S., Wilkinson, C., Richards, M. P., et al. (2015). The oldest case of decapitation in the New World (Lapa do Santo, East-Central Brazil). PLoS One, 10(9), e0137456.

Szulc, P., Seeman, E., & Delmas, P. D. (2000). Biochemical measurements of bone turnover in children and adolescents. Osteoporosis International, 11(4), 281–294.

Tchérémissinoff, Y., Martin, H., Texier, M., & Vaquer, J. (2005). Les sépultures chasséennes du site de Narbons à Montesquieu-de-Lauragais (Haute-Garonne). Gallia Préhistoire, 47, 1–32.

Tuteja, M., Bahirwani, S., & Balaji, P. (2012). An evaluation of third molar eruption for assessment of chronologic age: a panoramic study. Journal of Forensic Dental Sciences, 4(1), 13–18.

Valentin J. (2002). Basic anatomical and physiological data for use in radiological protection: reference values. IRCP Publication 89. Ann IRCP, 32, 3–4

van der Merwe, N. J. (1982). Carbon isotopes photosynthesis and archaeology. American Scientist, 70, 596–606.

van Klinken, G. J. (1999). Bone collagen quality indicators for palaeodietary and radiocarbon measurements. Journal of Archaeological Science, 26, 687–695.

van Oven, M., & Kayser, M. (2009). Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation. Human Mutation, 30(2), E386–E394.

Vika, E. (2009). Strangers in the grave? Investigating local provenance in a Greek Bronze Age mass burial using [delta]34S analysis. Journal of Archaeological Science, 36(9), 2024–2028.

Villalba-Mouco V, Sauqué V, Sarasketa-Gartzia I, Pastor MV, le Roux PJ, Vicente D, Utrilla P, & Salazar-García DC. (2018). Territorial mobility and subsistence strategies during the Ebro Basin Late Neolithic–Chalcolithic: A multi-isotope approach from San Juan cave (Loarre, Spain). Quaternary International (in press).

Virginia, R. A., & Delwiche, C. C. (1982). Natural 15N abundance of presumed N2 fixing and non N2 fixing plants from selected ecosystems. Oecologia, 57, 317–325.

Warinner, C., et al. (2014). Pathogens and host immunity in the ancient human oral cavity. Nature Genetic, 46, 336–344.

Willmes, M., McMorrow, L., Kinsley, L., Armstrong, R., Aubert, M., Eggins, S., Falguères, C., Maureille, B., Moffat, I., & Grün, R. (2014). The IRHUM (isotopic reconstruction of human migration) database — bioavailable strontium isotope ratios for geochemical fingerprinting in France. Earth System Science Data, 6(1), 117–122.

Wrangham, R. (1987). The significance of African apes for reconstructing human social evolution. In W. G. Kinzey (Ed.), The evolution of human behaviour: primate models (pp. 51–71). Albany: State University of New York Press.

Acknowledgements

These researches were funded by Institut Danone France/Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale 2015 partnership (Women and diet at the beginning of farming, 5th–3rd millennium BC, France: a bio-anthropological approach; Dir. G. Goude 2016-2017; http://institutdanone.org/nos-prix/femmes-alimentation-les-premieres-societes-agropastorales-ve-iiie-millenaires-av-j-c-france-approche-bio-anthropologique/) and Paléotime SARL.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The site was excavated under the supervision of AH and AC. Anthropological material was studied by JT. Isotope studies were conducted by GG, DCSG ,and GA. Dental calculus was studied by RCP. Genetic analyses were conducted by MR, MFD, and MHP, and parasitological study was carried out by MLB. The core of manuscript writing and editing was done by GG, DCSG, and RCP. This pilot study is part of a wider pluridisciplinary project for which other complementary data will be compared particularly to document the place of women at the onset of farming. Archaeozoological material was studied and provided for analysis by Léa Roux. We thank Mariska Carvalho and Julie Power for proofreading.

Corresponding authors

Electronic Supplementary Material

Supplementary material 1

Human and animal bone carbon, nitrogen, and sulphur isotope data, preservation indicators, and anthropological and burial information. Data in italic were not used in the interpretation as indicating badly preserved samples. (DOCX 39 kb)

Supplementary material 2

Teeth radiogenic Sr data of humans. Formation age: C = childhood (3.5–8 years old according to the tooth), A = “adolescence/early adulthood” [8.5–17.5 (or later) years old]. (DOCX 23 kb)

Supplementary material 3

Laboratory contamination monitoring blank slide testing for calculus micro remains study and results (DOCX 25 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Goude, G., Salazar-García, D.C., Power, R.C. et al. A Multidisciplinary Approach to Neolithic Life Reconstruction. J Archaeol Method Theory 26, 537–560 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-018-9379-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-018-9379-x