Abstract

Purpose

The objective of this study is to characterize the impact of exposure to cryoprotectants followed by vitrification on primordial follicle survival and activation using a fetal bovine model.

Methods

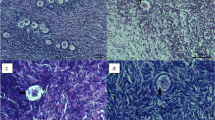

In the first study, fetal bovine cortical pieces were exposed to cryoprotectants with or without sucrose and cultured up to 7 days in the presence or absence of insulin. In the second study, cortical pieces were exposed to cryoprotectants with or without sucrose, vitrified, and cultured up to 7 days after warming in the presence or absence of insulin. Viability and morphology of follicles, as well as proliferation and/or DNA repair in ovarian tissue were analyzed.

Results

When compared to non-exposed controls, normal follicular morphology was affected in groups exposed to cryoprotectants only immediately post-exposure and after 1 day of culture, but improved by day 3 and did not significantly differ by day 7. Similarly, normal follicular morphology was compromised in vitrified groups after warming and on day 1 compared to controls, but improved by days 3 and 7. Proliferation and/or DNA repair in ovarian tissue was not affected by vitrification in this model. Cryoprotectant exposure and vitrification of ovarian tissue did not impair the activation of primordial follicles in response to insulin, although activation was delayed relative to non-exposed controls. Interestingly, sucrose had no noticeable protective effect.

Conclusion

Vitrified fetal bovine ovarian tissue has the intrinsic capacity to mitigate the immediate damage to primordial follicles’ morphology and retains the capacity to activate. These findings provide a basis for a successful cryopreservation protocol for ovarian cortical tissue in other species including humans.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Chung K, Donnez J, Ginsburg E, Meirow D. Emergency IVF versus ovarian tissue cryopreservation: decision making in fertility preservation for female cancer patients. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(6):1534–42.

Donnez J, Dolmans M-M. Cryopreservation and transplantation of ovarian tissue. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53(4):787–96.

West ER, Zelinski MB, Kondapalli LA, Gracia C, Chang J, Coutifaris C, et al. Preserving female fertility following cancer treatment: current options and future possibilities. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;53(2):289–95.

Comizzoli P, Songsasen N, Wildt DE. Protecting and extending fertility for females of wild and endangered mammals. Cancer Treat Res. 2010;156:87–100.

Santos RR, Amorim C, Cecconi S, Fassbender M, Imhof M, Lornage J, et al. Cryopreservation of ovarian tissue: an emerging technology for female germline preservation of endangered species and breeds. Anim Reprod Sci. 2010;122(3-4):151–63.

Depalo R, Loverro G, Selvaggi L. In vitro maturation of primordial follicles after cryopreservation of human ovarian tissue: problems remain. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38(3):153–7.

Donnez J, Silber S, Andersen CY, Demeestere I, Piver P, Meirow D, et al. Children born after autotransplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue. A review of 13 live births. Ann Med. 2011;43(6):437–50.

Karlsson JO, Toner M. Long-term storage of tissues by cryopreservation: critical issues. Biomaterials. 1996;17(3):243–56.

Fahy GM, MacFarlane DR, Angell CA, Meryman HT. Vitrification as an approach to cryopreservation. Cryobiology. 1984;21(4):407–26.

Fahy GM. The relevance of cryoprotectant “toxicity” to cryobiology. Cryobiology. 1986;23(1):1–13.

Courbière B, Baudot A, Mazoyer C, Salle B, Lornage J. Vitrification: a future technique for ovarian cryopreservation? Physical basis of cryobiology, advantages and limits. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2009;37(10):803–13.

Castro SV, Carvalho AA, Silva CMG, Santos FW, Campello CC, Figueiredo JR, et al. Fresh and vitrified bovine preantral follicles have different nutritional requirements during in vitro culture. Cell Tissue Bank. 2014 Mar 8.

Wang X, Catt S, Pangestu M, Temple-Smith P. Successful in vitro culture of pre-antral follicles derived from vitrified murine ovarian tissue: oocyte maturation, fertilization, and live births. Reproduction. 2011;141(2):183–91.

Wang Y, Xiao Z, Li L, Fan W, Li S-W. Novel needle immersed vitrification: a practical and convenient method with potential advantages in mouse and human ovarian tissue cryopreservation. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(10):2256–65.

Fortune JE, Yang MY, Muruvi W. In vitro and in vivo regulation of follicular formation and activation in cattle. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2011;23(1):15–22.

Evans HE, Sack WO. Prenatal development of domestic and laboratory mammals: growth curves, external features and selected references. Zentralbl Veterinarmed C. 1973;2(1):11–45.

Wandji SA, Srsen V, Voss AK, Eppig JJ, Fortune JE. Initiation in vitro of growth of bovine primordial follicles. Biol Reprod. 1996;55(5):942–8.

Yang MY, Fortune JE. The capacity of primordial follicles in fetal bovine ovaries to initiate growth in vitro develops during mid-gestation and is associated with meiotic arrest of oocytes. Biol Reprod. 2008;78(6):1153–61.

Moldovan G-L, Pfander B, Jentsch S. PCNA, the maestro of the replication fork. Cell. 2007;129(4):665–79.

Yavin S, Arav A. Measurement of essential physical properties of vitrification solutions. Theriogenology. 2007;67(1):81–9.

Vajta G, Nagy ZP. Are programmable freezers still needed in the embryo laboratory? Review on vitrification. Reprod BioMed Online. 2006;12(6):779–96.

Moniruzzaman M, Bao RM, Taketsuru H, Miyano T. Development of vitrified porcine primordial follicles in xenografts. Theriogenology. 2009;72(2):280–8.

Fathi R, Valojerdi MR, Eimani H, Hasani F, Yazdi PE, Ajdari Z, et al. Sheep ovarian tissue vitrification by two different dehydration protocols and needle immersing methods. Cryo Letters. 2011;32(1):51–6.

Salehnia M, Sheikhi M, Pourbeiranvand S, Lundqvist M. Apoptosis of human ovarian tissue is not increased by either vitrification or rapid cooling. Reprod BioMed Online. 2012;25(5):492–9.

Amorim CA, David A, Van Langendonckt A, Dolmans M-M, Donnez J. Vitrification of human ovarian tissue: effect of different solutions and procedures. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(3):1094–7.

Fatehi R, Ebrahimi B, Shahhosseini M, Farrokhi A, Fathi R. Effect of ovarian tissue vitrification method on mice preantral follicular development and gene expression. Theriogenology. 2013 Oct 1.

Xiao Z, Wang Y, Li L, Luo S, Li S-W. Needle immersed vitrification can lower the concentration of cryoprotectant in human ovarian tissue cryopreservation. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(6):2323–8.

Xiao Z, Wang Y, Li L-L, Li S-W. In vitro culture thawed human ovarian tissue: NIV versus slow freezing method. Cryo Letters. 2013;34(5):520–6.

Klocke S, Bündgen N, Köster F, Eichenlaub-Ritter U, Griesinger G. Slow-freezing versus vitrification for human ovarian tissue cryopreservation. Arch Gynecol Obstet. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2014 Aug 13;:1–8.

Amorim CA, Jacobs S, Devireddy RV, Van Langendonckt A, Vanacker J, Jaeger J, et al. Successful vitrification and autografting of baboon (Papio anubis) ovarian tissue. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(8):2146–56.

Liu J, Cheng KM, Silversides FG. Novel needle-in-straw vitrification can effectively preserve the follicle morphology, viability, and vascularization of ovarian tissue in Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica). Anim Reprod Sci. 2012;134(3-4):197–202.

Kagawa N, Silber S, Kuwayama M. Successful vitrification of bovine and human ovarian tissue. Reprod BioMed Online. 2009;18(4):568–77.

Celestino JJH, Santos RRD, Melo MAP, Rodrigues APR, Figueiredo JR. Vitrification of bovine ovarian tissue by the solid-surface vitrification method. Biopreserv Biobank. 2010;8(4):219–21.

Amorim CA, Curaba M, Van Langendonckt A, Dolmans M-M, Donnez J. Vitrification as an alternative means of cryopreserving ovarian tissue. Reprod BioMed Online. 2011;23(2):160–86.

Amorim CA, David A, Dolmans M-M, Camboni A, Donnez J, Van Langendonckt A. Impact of freezing and thawing of human ovarian tissue on follicular growth after long-term xenotransplantation. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2011;28(12):1157–65.

David A, Van Langendonckt A, Gilliaux S, Dolmans M-M, Donnez J, Amorim CA. Effect of cryopreservation and transplantation on the expression of kit ligand and anti-Mullerian hormone in human ovarian tissue. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(4):1088–95.

von Schönfeldt V, Chandolia R, Kiesel L, Nieschlag E, Schlatt S, Sonntag B. Advanced follicle development in xenografted prepubertal ovarian tissue: the common marmoset as a nonhuman primate model for ovarian tissue transplantation. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(4):1428–34.

Oktem O, Alper E, Balaban B, Palaoglu E, Peker K, Karakaya C, et al. Vitrified human ovaries have fewer primordial follicles and produce less anti-Müllerian hormone than slow-frozen ovaries. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(8):2661–1.

Huang L, Mo Y, Wang W, Li Y, Zhang Q, Yang D. Cryopreservation of human ovarian tissue by solid-surface vitrification. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;139(2):193–8.

Amorim CA, Dolmans M-M, David A, Jaeger J, Vanacker J, Camboni A, et al. Vitrification and xenografting of human ovarian tissue. Fertility and Sterility. 2012 Nov;98(5):1291–8.e1–2.

Oktay K, Schenken RS, Nelson JF. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen marks the initiation of follicular growth in the rat. Biol Reprod. 1995;53(2):295–301.

Wandji SA, Srsen V, Nathanielsz PW, Eppig JJ, Fortune JE. Initiation of growth of baboon primordial follicles in vitro. Hum Reprod. Oxford University Press; 1997 Sep 1;12(9):1993–2001.

Lan C, Xiao W, Xiao-Hui D, Chun-Yan H, Hong-Ling Y. Tissue culture before transplantation of frozen-thawed human fetal ovarian tissue into immunodeficient mice. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(3):913–9.

Ulrich HD, Takahashi T. Readers of PCNA modifications. Chromosoma. 2013;122(4):259–74.

Bao R-M, Yamasaka E, Moniruzzaman M, Hamawaki A, Yoshikawa M, Miyano T. Development of vitrified bovine secondary and primordial follicles in xenografts. Theriogenology. 2010;74(5):817–27.

Carvalho AA, Faustino LR, Silva CMG, Castro SV, Luz HKM, Rossetto R, et al. Influence of vitrification techniques and solutions on the morphology and survival of preantral follicles after in vitro culture of caprine ovarian tissue. Theriogenology. 2011;76(5):933–41.

Fathi R, Valojerdi MR, Salehnia M. Effects of different cryoprotectant combinations on primordial follicle survivability and apoptosis incidence after vitrification of whole rat ovary. Cryo Letters. 2013;34(3):228–38.

Figueiredo JR, Hulshof SC, van den Hurk R, Ectors FJ, Fontes RS, Nusgens B, et al. Development of a combined new mechanical and enzymatic method for the isolation of intact preantral follicles from fetal, calf and adult bovine ovaries. Theriogenology. 1993;40(4):789–99.

Bos-Mikich A, Marques L, Rodrigues JL, Lothhammer N, Frantz N. The use of a metal container for vitrification of mouse ovaries, as a clinical grade model for human ovarian tissue cryopreservation, after different times and temperatures of transport. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012;29(11):1267–71.

Wang AW, Zhang H, Ikemoto I, Anderson DJ, Loughlin KR. Reactive oxygen species generation by seminal cells during cryopreservation. Urology. 1997;49(6):921–5.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cargill Regional Beef for the donation of bovine ovaries. The cooperation of John Couture at Cargill is gratefully acknowledged. The authors also thank Dr. Mark Roberson for the use of his storage facilities and Mary Lou Norman for her assistance with histological preparations.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Funding

This research was supported by the United States Department of Agriculture Multistate Project (NE-1227).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Capsule

Cryoprotectant exposure and vitrification of fetal bovine ovarian tissue do not cause long-term damage to follicle structure or affect the capacity of primordial follicles to activate.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mouttham, L., Fortune, J.E. & Comizzoli, P. Damage to fetal bovine ovarian tissue caused by cryoprotectant exposure and vitrification is mitigated during tissue culture. J Assist Reprod Genet 32, 1239–1250 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-015-0543-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-015-0543-x