Abstract

A windfall in a developing economy with capital scarcity and investment adjustment costs facing a temporary windfall should be used to give more consumption to poorer present generations and to speed up development by ramping up public investment and paying off debt taking due account of the increasing inefficiency as investment gets ramped up. The optimal strategy requires negative genuine saving; the permanent income requires zero genuine saving. The optimal real consumption increments are smaller once one allows for absorption constraints resulting from Dutch disease and sluggish adjustment of ‘home-grown’ public capital.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Surveys of harnessing windfalls of foreign exchange in developing economies are offered in Collier et al. (2010) and van der Ploeg and Venables (2012). A useful two-period analysis is presented in Venables (2010). Here, we focus on the sources of bottlenecks that must be faced when ramping up public investment in developing economies.

Berg et al. (2011) provides a very interesting complimentary analysis of a fully specified, discrete-time DSGE model with a tradable, non-tradeable and resource sector where the cost of ramping up public investment also increases. The difference is, on the one hand, that the specification of these costs differs from our internal cost of adjustment approach which is derived from recent public investment measures of inefficiency (Dabla-Norris et al. 2011; Gupta et al. 2011), and, on the other hand, the emphasis is on ad hoc saving, spending, and investment rules whilst the emphasis in our continuous-time model is on deriving optimal responses to exogenous windfalls.

We abstract from population growth π and productivity growth γ but we can easily relax this by supposing that all quantity variables including the windfall are in intensive form and scaled by e (γ+π)t. The interest rate r thus corresponds to the growth-corrected world interest rate, where the growth rate of the economy equals γ+π. Given the assumption that (3) corresponds to a utilitarian social welfare function, the parameter ρ corresponds to the rate of time preference minus the term π+(1−1/σ)γ.

A derivation of the permanent income rule for the temporary oil windfall of Ghana, its comparison with the bird-in-hand rule and the constitutional rule, and its sensitivity to population growth, myopia, intertemporal substitution and finite lives is given in van der Ploeg et al. (2011).

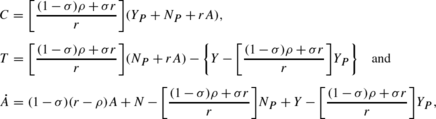

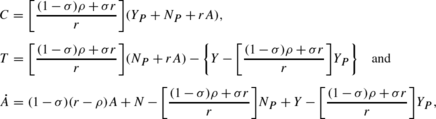

In general, we see that if r≠ρ, Eqs. (5) and (6) become

where with r>ρ the term in square brackets is less (greater) than one if σ is greater (less) than one. So, if σ>1, the intertemporal substitution dominates the income effect and the propensity to consume out of permanent income is less than unity and from (4) private consumption and government transfers rise over time. If σ<1, the income effect dominates. Hence, the propensity to consume out of resource wealth exceeds unity so the paths of private consumption and transfers fall over time.

The coefficient on skilled labor is estimated to be 0.336. We could combine skilled labor and private capital, but abstract from that. A recent meta-regression analysis from widely varying estimates suggests that the average output elasticity of public capital is significant and estimated at 0.15, but imposing constant returns to scale with respect to private capital and labor leads to larger estimates and they therefore use a benchmark estimate for β′ of 0.17 (Bom and Ligthart 2010). But as this study is based on available estimates from past research, it could not make use of an efficiency-adjusted measure of public capital to estimate the effect on growth.

Note that average “q” equals marginal “q”, analogously to Tobin’s Q for private capital (cf., Hayashi 1982).

Hence, there is no empirical support for the alternative hypothesis Π=Π(d−N p /[r(Y+N)]).

We use a Runge–Kutta algorithm to solve (15a)–(15d) and (16) from time zero to some horizon T with initial conditions K(0)=K 0, D(0)=D 0, and guesses for C(0) and q(0). A Newton–Raphson method is then used to adjust C(0) and q(0) until C(T)=C ∗ and q(T)=q ∗(as well as D(T)=D ∗ andS(T)=S ∗) are satisfied. T is then increased until it no longer has an effect on the C(0) and q(0) that are needed to make the economy jump to its stable manifold. Alternatively, a spectral decomposition algorithm (e.g., Buiter 1984) is used to solve the linearized model.

The level of genuine savings under the optimal rule without the windfall is positive, since the country is accumulating assets along its development path. With the windfall, the level of genuine savings turns negative as the country uses it to pay off its debt more rapidly.

For simplicity, we suppose the same unit-expenditure functions for private consumption and public investment.

References

Acemoglu, D., Aghion, P., Bursztyn, L., & Hemous, D. (2012). The environment and directed technical change. American Economic Review, 102(1):131–166.

Akitobi, B., & Stratmann, T. (2008). Fiscal policy and financial markets. Economic Journal, 118(533), 1971–1985.

Barnett, S., & Ossowski, R. (2003). Operational aspects of fiscal policy in oil-producing countries. In J. Davis, R. Ossowski, & A. Fedelino (Eds.), Fiscal policy formulation and implementation in oil-producing countries. Washington: International Monetary Fund.

Berg, A., Portillo, R., Yang, S.-C. S., & Zanna, L.-F. (2011). Government investment in resource abundant low-income countries. Washington: International Monetary Fund. mimeo.

Bom, P., & Ligthart, J. E. (2010). What have we learned from three decades of research on the productivity of public capital. Working Paper No. 2206, CESifo, Munich.

Bosschini, A. D., Petterson, J., & Roine, J. (2007). Resource curse or not: a question of appropriability. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 109, 593–616.

Buiter, W. H. (1984). Saddlepoint problems in continuous time rational expectations models: a general method and some macroeconomic examples. Econometrica, 52(3), 665–680.

Collier, P., van der Ploeg, F., Spence, M., & Venables, A. J. (2010). Managing resource revenues in developing economies. IMF Staff Papers, 57(1), 84–118.

Cordon, W. M. (1984). Booming sector and Dutch disease economics: survey and consolidation. Oxford Economic Papers, 36, 359–380.

Cordon, W. M., & Neary, J. P. (1982). Booming sector and de-industrialisation in a small open economy. Economic Journal, 92, 825–848.

Dabla-Norris, E., Brumby, J., Kyobe, A., Mills, Z., & Papageorgiou, C. (2011). Investing in public investment: an index of public investment efficiency. Working Paper 11/37, International Monetary Fund, Washington, D.C.

Epstein, L. G., & Zin, S. E. (1989). Substitution, risk aversion, and the temporal behavior of consumption growth and asset returns: I. A theoretical framework. Econometrica, 57(4), 937–969.

Feldstein, M., & Horioka, C. (1980). Domestic saving and international capital flows. Economic Journal, 90(358), 314–329.

Gupta, S., Kangur, A., Papageorgiou, C., & Wane, A. (2011). Efficiency-adjusted public capital and growth. Working Paper 11/217, International Monetary Fund, Washington, D.C.

Hartwick, J. M. (1977). Intergenerational equity and the investment of rents from exhaustible resources. American Economic Review, 67, 972–974.

Hayashi, F. (1982). Tobin’s marginal Q and average Q: a neoclassical interpretation. Econometrica, 50(1), 213–224.

Ketkar, S., & Ratha, D. (2009). New paths to funding. Finance and Development, 46(2).

Mehlum, H., Moene, K., & Torvik, R. (2006). Institutions and the resource curse. Economic Journal, 160, 1–20.

Neary, J. P. (1988). Determinants of the equilibrium real exchange rate. American Economic Review, 78(1), 210–215.

van der Ploeg, F. (1993). A closed-form solution for a model of precautionary saving. Review of Economic Studies, 60(2), 385–396.

van der Ploeg, F. (2010). Why do many resource-rich countries have negative genuine saving? Anticipation of better times or rapacious rent seeking. Resource and Energy Economics, 32, 28–44.

van der Ploeg, F. (2011). Natural resources: curse or blessing? Journal of Economic Literature, 49(2), 366–420.

van der Ploeg, F., & Poelhekke, S. (2009). Volatility and the natural resource curse. Oxford Economic Papers, 61(4), 727–760.

van der Ploeg, F., & Venables, A. J. (2011a). Harnessing windfall revenues: optimal policies for resource-rich developing economies. Economic Journal, 121, 1–31.

van der Ploeg, F., & Venables, A. J. (2011b). Absorbing a windfall of foreign exchange: Dutch disease dynamics. Research Paper 52, Oxcarre, Department of Economics, University of Oxford.

van der Ploeg, F., & Venables, A. J. (2012). Natural resource wealth: how not to squander it. Annual Reviews of Economics, 4.

van der Ploeg, F., Stefanski, R., & Wills, S. (2011). Harnessing oil revenues in Ghana. Policy Paper 12, OxCarre, University of Oxford and International Growth Centre, LSE.

Pritchett, L. (2000). The tyranny of concepts: CUDIE (Cumulated, Depreciated, Investment Effort) is not capital. Journal of Economic Growth, 5, 361–384.

Sachs, J. D., & Warner, A. M. (1997). Natural resource abundance and economic growth. In G. Meier & J. Rauch (Eds.), Leading issues in economic development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Torvik, R. (2001). Learning by doing and the Dutch disease. European Economic Review, 45, 285–306.

Venables, A. J. (2010). Resource rents: when to spend and how to save. International Tax and Public Finance, 17, 340–356.

van Wijnbergen, S. J. (1984). The Dutch disease: a disease after all? Economic Journal, 94(373), 41–55.

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the BP funded Oxford Centre for the Analysis of Resource Rich Economies is gratefully acknowledged. Useful discussions with Bernardin Akitoby, Andrew Berg, Philip Daniel, Sanjeev Gupta, Jenny Ligthart, Cathy Pattillo, Radek Stefanski, Simone Valente, Tony Venables, David Wildasin, and Sam Wills and the detailed and insightful comments of Ruud de Mooij are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Also F. van der Ploeg is affiliated with the VU University Amsterdam, CEPR and CESifo.

Based on the keynote lecture which was presented at the 67th Annual Congress of the International Institute of Public Finance, Ann Arbor, 8–11 August 2011.

Appendix

Appendix

Section 3.2

The optimality conditions for the problem of maximizing (3) subject to (7), (8), (11), and C=(1−α′)ES β+T follow from the Hamiltonian function

where λ A is the shadow price of A and λ S of S. They are given by:

Equations (A.2a) and (A.2c) can be combined to yield (4). Defining q≡λ S /λ A , we obtain (12) from (A.2b). Equations (A.2a), (A.2c), (A.2d), and (12) can be combined to give (13).

Section 3.2

The government maximizes (3) subject to (7), (8), (11), C=(1−α′)ES β+T and (14), where D=−A. The Hamiltonian function becomes

and yields the optimality conditions (A.2a), (A.2b),

Section 6

To obtain the first-order conditions in Sect. 6, we define the Hamiltonian function:

where λ S , λ D , λ N denote the shadow value of S, minus the shadow cost of D, and the Lagrange multiplier corresponding to the condition for equilibrium in the market for non-tradables. This yields:

Combining (A.4a) and (A.4b), we get I=(q−1)S/ϕ and (17) where q≡λ S /U′(C). Putting (A.4c) into (A.4a) we get

where use has been made of e′(p)(C+J)=Y p (p,S). Using this and r ∗=ρ in (A.4e) gives (15a′). Using (A.4a) in (A.4d) gives

or

From (15a′), we get

so we have

from q≡λ S /U′(C) and thus (15c′). Equation (15d′) follows from substituting e(p)C−Y(p,S) for government transfers. To obtain (17′), we make use of the GNP function (18) including

to totally differentiate (17).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van der Ploeg, F. Bottlenecks in ramping up public investment. Int Tax Public Finance 19, 509–538 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-012-9225-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-012-9225-0

Keywords

- Optimal management of windfalls

- Economic development

- Capital scarcity

- Public capital

- PIMI

- Investment adjustment costs

- Absorption constraints

- Genuine saving

- Dutch disease