Abstract

We examine listed tuition and institutional aid practices within the US private sector, a sector where market pressures are relatively strong and consequently influence organizational behavior. We present a conceptual framework that highlights three psychological aspects of pricing—the price-quality heuristic, ego-expressive aspects of aid, and the silver lining effect—that can influence the attractiveness of specific pricing strategies to prospective students. We review relevant literature from psychology, marketing, and behavioral economics to illustrate that these three psychological aspects should be especially important in higher education. Furthermore, we identify pricing strategies that could position colleges and universities advantageously within market-based competition due to these aspects. The key elements of the strategy include high listed tuition, widespread institutional aid awards, and aid awards that are framed in a manner that confers distinction upon the recipient. We use data from a range of sources to describe the nuanced ways in which these pricing strategies are used within the US private sector. Our empirical analysis reveals that many schools, especially those in the middle of the prestige hierarchy, provide institutional aid to all or almost all of their incoming students, which allows them to set listed tuition prices well above the demonstrated willingness to pay of students. We also present evidence that aid awards are named in a manner that exaggerates the distinction conferred by the award. Our conclusion highlights implications of our work for students, organizations, policymakers, and future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although we do not discuss in the text, past work has highlighted other potential ways—beyond the price-quality heuristic—that a high listed price could make an institution more attractive to students. Thaler (1985, 2015) noted that high listed prices also set a high reference point that can lead consumers to receive more transaction utility when they pay a net price that is well below the listed price. Organizational theorists (e.g. Askin and Bothner 2016) highlight the connection in private higher education between listed prices and status, a concept that only partially overlaps with quality.

A few authors have briefly mentioned potential psychological aspects of institutional aid. Archibald and Feldman (2011) noted that students and families value the cachet of receiving a scholarship, especially a named scholarship. Caskey (2018) stated that students who are notified that they qualify for a scholarship may feel wanted or honored.

We use exact dollar figures (t = $37,000; a = $10,000) in our discussion of Fig. 1 to make Thaler’s ideas easier to grasp. We are not claiming that these dollar figures relate to specific points on the graph in Fig. 1. We do not have a precise understanding of the specific ranges associated with the flat and steep parts of the gain and loss curves. We can only say with confidence that a move from a $0 gain to a positive gain will contain, at least in part, the steep part of the gain curve.

The Higher Education Act of 1965 (amended October 29, 2011) requires that Title IV institutions enrolling full-time, first-time, degree or certificate-seeking undergraduate students provide a publicly available net price calculator (NPC) on their website. The NPC allows a student to estimate her net price of attendance (defined as total cost of attendance minus any federal, state, and institutional aid) based on what similar students paid in a previous year.

Net price calculators differ across schools such that the required amount and type of information vary. While collecting award data, we sought to provide uniform criteria across schools to the extent possible. For our very low values of academic criteria, we used a 2.0 high school grade point average, a score of 200 on the SAT math test, and a score of 200 on the SAT verbal test. When these low academic values were used and no financial need was specified, we received estimated aid awards for 32 of our 51 schools. For the remaining 19, we increased the academic criteria upwards until we observed an aid award. The net price calculators at three of these schools did not utilize academic criteria, so this approach could be not be used at these schools. For the other 16 schools, 13 reported aid awards for academic criteria at or below a 3.0 GPA, 500 SAT math score, and 500 SAT verbal score. In total, we were able to obtain estimated aid awards for 45 of the 51 institutions.

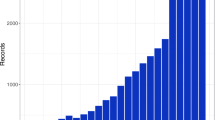

The share of institutions that provided aid to 100% of incoming first-time full-time students was 4.1% in 2001/02, and then steadily rose to 23.5% in 2015/16.

An example of the spreading of information is a recent article in the Wall Street Journal entitled “Prizes for Everyone”, which describes the use of widespread aid awards by some private colleges (Korn 2018).

To confirm that these visual relationships also hold in a parametric setting, we estimated Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regressions. Listed tuition was regressed on US News ranking, and the share of students receiving aid was regressed on the quadratic of US News rankings. All coefficients were highly significant with t statistics close to 10. See the online appendix for additional details.

Past research (e.g. Geiger 2004; Hoxby 2009; Taylor and Cantwell 2019; Winston 1999) has provided a range of evidence that highlights large differences in student demand between elite institutions and other institutions, and smaller gaps between institutions in other portions of the ranking hierarchy.

To further confirm that both admittance rates and yield rates have a nonlinear relationship with US News rankings while listed tuition did not, we estimated spline regressions, where the knot was set at the point where US News ranking equals 51. For these regressions, the difference between the coefficient for top 50 schools and the coefficient for non-top 50 schools was always statistically significant when admittance or yield rates were the dependent variable. In contrast, the equivalent difference was not statistically significant when listed tuition was the dependent variable. See the online appendix for additional details.

The drop in the predicted share of incoming students in Fig. 2 that occurs further down the rankings is partially driven by very low values for the share of students receiving aid at several historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) that are ranked between 190 and 240. These HBCUs also have relatively low values for listed tuition.

Of the remaining 40%, half are simply described as “grants and scholarships.” The inclusion of the term scholarship could imply that the award conferred distinction, but the recipient could also interpret this to mean they simply received a basic grant. To be conservative regarding our definition for academic distinction, we do not include these cases.

Data from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Survey (NPSAS) provide further evidence that minimum aid awards are substantial at four-year privates ranked outside of the top 50 in US News and World Report rankings. For the 2015–2016 NPSAS, students at these institutions who have no financial need and academic test scores in the bottom quartile for their institution received $10,265, on average.

Our list is not exhaustive as it simply contains those items emphasized in the literature that we reviewed. Additional considerations, such as existing perceptions of listed prices, may play a role. In countries where the most prestigious institutions charge no tuition or very low levels, prospective students may be less likely to employ the price-quality heuristic even when comparing two institutions from the private sector that receive no governmental subsidies.

References

Altringer, L., & Summers, J. (2015). Is college pricing power pro-cyclical? Research in Higher Education, 56(8), 777–792.

Archibald, R. B., & Feldman, D. H. (2011). Why does college cost so much? New York: Oxford University Press.

Askin, N., & Bothner, M. (2016). Status-aspirational pricing. Administrative Science Quarterly, 61(2), 217–253.

Avery, C., & Hoxby, C. M. (2004). Do and should financial aid packages affect students’ college choices? In C. M. Hoxby (Ed.), College choices: the economics of where to go, when to go, and how to pay for it (pp. 239–302). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Behaunek, L., & Gansemer-Topf, A. M. (2019). Tuition discounting at small, private, baccalaureate institutions: reaching a point of no return? Journal of Student Financial Aid, 48(3), 1–28.

Breneman, D. W. (1994). Liberal arts colleges: thriving, surviving, or endangered? Washington, D.C: Brookings Institution.

Breneman, D. W., Doti, J. L., & Lapovsky, L. (2007). Financing private colleges and universities: the role of tuition discounting. In M. B. Paulson (Ed.), Finance of higher education: theory, research, policy & practice (pp. 461–479). New York: Algora Publishing.

Caskey, J. P. (2018). Tuition discounting in Liberal Arts Colleges. Change, 50(6), 52–58.

Cheslock, J. J., & Riggs, S. O. (2020). Ever-increasing listed tuition and institutional aid: the role of net price differentials by year of study. Unpublished manuscript, The Pennsylvania State University.

Chetty, R., Friedman, J., Saez, E., Turner, N., & Yagan, D. (2017). Mobility report cards: the role of colleges in intergenerational mobility. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper #23618.

Clotfelter, C. T. (2017). Unequal colleges in the age of disparity. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Compeau, L. D., & Grewal, D. (1998). Comparative price advertising: an integrative review. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 17(2), 257–273.

Cook, P. J., & Frank, R. H. (1993). The growing concentration of top students at elite schools. In C. T. Clotfelter & M. Rothschild (Eds.), Studies of supply and demand in higher education (pp. 121–44). Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press.

Curs, B. R., & Singell, L. D. (2010). Aim high or go low? Pricing strategies and enrollment effects when the net price elasticity varies with need and ability. Journal of Higher Education, 81(4), 515–543.

Doyle, W. R. (2010). Changes in institutional aid, 1992-2003: the evolving role of merit aid. Research in Higher Education, 51(8), 789–810.

Duffy, E. A., & Goldberg, I. (1998). Crafting a class: college admissions and financial aid, 1955-1994. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ehrenberg, R. G. (2000). Tuition rising: why college costs so much. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Geiger, R. L. (2004). Knowledge and money: research universities and the paradox of the marketplace. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Grawe, N. D. (2018). Demographics and the demand for higher education. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Griffith, A. L. (2011). Keeping up with the Joneses: Institutional changes following the adoption of a merit aid policy. Economics of Education Review, 30(5), 1022–1033.

Heller, D. E. (1997). Student price response in higher education. Journal of Higher Education, 68(6), 624–659.

Hemelt, S. W., & Marcotte, D. E. (2011). The impact of tuition increases on enrollment at public colleges and universities. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 33(4), 435–457.

Hoxby, C. M. (2009). The changing selectivity of American colleges. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23(4), 95–118.

Johnstone, D. B., & Marcucci, P. (2010). Financing higher education worldwide: Who pays? Who should pay? Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291.

Korn, M. (2018). Prizes for everyone: how colleges use scholarships to lure students. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/prizes-for-everyone-how-colleges-usescholarships-to-lure-students-15239574000.

Krishna, A., Briesch, R., Lehmann, D. R., & Yuan, H. (2002). A meta-analysis of the impact of price presentation on perceived savings. Journal of Retailing, 78(2), 101–118.

Leavitt, H. J. (1954). A note on some experimental findings about the meanings of price. The Journal of Business, 12(3), 205–210.

Leslie, L. L., & Johnson, G. P. (1974). The market model and higher education. Journal of Higher Education, 45(1), 1–20.

Leslie, L. L., & Brinkman, P. T. (1987). Student price response in higher education: The student demand studies. Journal of Higher Education, 58(2), 181–204.

Longmire and Company. (2013). Your value proposition: how prospective students and parents perceive value and select colleges. Available https://www.longmire-co.com/documents/studies/Value_Proposition_Study_Report.pdf. Accessed 29 November 2018.

Marginson, S. (2004). Competition and markets in higher education: a ‘glonacal’ analysis. Policy Futures in Education, 2(2), 175–244.

Martin, R. E. (2011). The college cost disease: higher cost and lower quality. Cheltenham, Gloucestershire: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Massy, W. (2003). Honoring the trust: quality and cost containment in higher education. Bolton: Anker Publishing Company.

McPherson, M. S., & Schapiro, M. O. (1998). The student aid game: meeting need and rewarding talent in American higher education. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rao, A. R., & Monroe, K. B. (1989). The effect of price, brand name, and store name on buyer’s perceptions of product quality: an integrative review. Journal of Marketing Research, 26(3), 351–357.

Rothschild, M., & White, L. J. (1995). The analytics of pricing of higher education and other services in which customers are inputs. Journal of Political Economy, 103(3), 573–586.

Schindler, R. M. (1998). Consequences of perceiving oneself as responsible for obtaining a discount: evidence for smart-shopper feelings. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 7(4), 371–392.

Schindler, R. M. (1989). The excitement of getting a bargain: some hypotheses concerning the origins and effects of smart-shopper feelings. Advances in Consumer Research, 16, 447–453.

Scitovsky, T. (1945). Some consequences of the habit of judging quality by price. The Review of Economic Studies, 12(2), 100–105.

Slaughter, S., & Cantwell, B. (2012). Transatlantic moves to the market: the United States and the European Union. Higher Education, 63(5), 583–606.

Slaughter, S., & Leslie, L. L. (1997). Academic capitalism: politics, policies, and the entrepreneurial university. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Slaughter, S., & Rhoades, G. (2004). Academic capitalism and the new economy: markets, state, and higher education. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Summers, J. A. (2004). Net tuition revenue generation at private liberal arts colleges. Education Economics, 12(3), 219–230.

Taylor, B. J., & Cantwell, B. (2019). Unequal higher education: wealth, status, and student opportunity. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Thaler, R. H. (1985). Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing Science, 27(1), 15–25.

Thaler, R. H. (2015). Misbehaving: the making of behavioral economics. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Trow, M. (1984). The analysis of status. In B. R. Clark (Ed.), Perspectives on higher education (pp. 132–164). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Völckner, F., & Hofmann, J. (2007). The price-perceived quality relationship: a meta-analytic review and assessment of its determinants. Marketing Letters, 18(3), 181–196.

Weisbrod, B. A., Ballou, J. P., & Asch, E. D. (2008). Mission and money: understanding the university. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Winston, G. C. (1992). Hostility, maximization, & the public trust. Change, 24(4), 20–27.

Winston, G. C. (1999). Subsidies, hierarchies, and peers: the awkward economics of higher education. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 13(1), 13–36.

Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. The Journal of Marketing, 52, 2–22.

Zhang, L. (2007). Nonresident enrollment demand in public higher education: an analysis at national, state, and institutional levels. The Review of Higher Education, 31(1), 1–25.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Deborah Anderson, Jesse Rine, Kelly Rosinger, and participants of the Center for the Study of Higher Education meetings at the Pennsylvania State University for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 21 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cheslock, J.J., Riggs, S.O. Psychology, market pressures, and pricing decisions in higher education: the case of the US private sector. High Educ 81, 757–774 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00572-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00572-9