Abstract

We present experimental evidence regarding individual and group decisions over time. Static and longitudinal methods are combined to test four conditions on time preferences: impatience, stationarity, age independence, and dynamic consistency. Decision making in groups should favor coordination via communication about voting intentions. We find that individuals are neither patient nor consistent, that groups are both patient and highly consistent, and that information exchange between participants helps groups converge to stable decisions. Finally we provide additional evidence showing that our results are driven by the specific role of groups and not by either repeated choices or individual preferences when choosing for other subjects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Meier and Sprenger (2015) also report non-negligible time-variations in experimental measures.

We could not completely rule out wealth effects. For individuals who are paid for real at \(\ell + \Delta \), those previous gains might have affected behavior in Session 3. Since only three subjects met this condition, it is reasonable to assume that wealth effects did not bias our results.

That axiomatization is based on five axioms—three technical conditions (continuity, sensitivity and boundedness), stationarity and an independence axiom—applied to time sequences (non-complementarity). Bleichrodt et al. (2008) clarify Koopmans’ axioms, especially independence and stationarity, and propose a clean and complete preference axiomatization of discounted utility.

In the discounted utility model, violations of stationarity are not compatible with an exponential discount function; hence they are represented by a wide range of alternative discount functions. Of these, the most widely used are hyperbolic discount functions (Phelps and Pollak 1968; Loewenstein and Prelec 1992). Yet violations of stationarity can be accommodated also by nonhyperbolic discount functions (Bleichrodt et al. 2009), which can more flexibly incorporate increasing impatience.

Our “stationarity” is their “cross-sectional time consistency”.

For example, age independence is violated by a man who prefers one apple on his 21st birthday to two apples the day after but in all other situations prefers two apples a day later. Such a decision maker exhibits dynamic consistency but not stationarity.

The tables in Appendix 1 show the values of the indexes of stationarity, age independence, and dynamic consistency for both individuals and groups (and their significance levels).

Two subjects dropped out after session 1 and two more after session 2. The resultant missing data precluded our simulating a utilitarian criterion for three of the groups, which is why the simulation results are given only for nine of the twelve groups.

With regard to one of Session 1’s three tasks (viz., elicitation of \(x_1^3\)), we found that group decisions were more patient than individual decisions (\(p=0.04\)).

Giné et al. (2014) find that 50 % of the choices satisfy stationarity and 35 % satisfy dynamic consistency. In Study 1 of Sayman and Öncüler (2009), the authors find no evidence favoring time inconsistency: 58 % of the choices were dynamically consistent. Halevy (2015) report that 48 % of time-consistent subjects and 56 % of all subjects exhibit stationary preferences.

Rather than voting on a common decision, subjects could have coordinated on a sharing rule (Millner and Heal 2014). Because this alternative mechanism did not allowed for direct comparisons between individual and collective preferences, we opted for a political (voting) approach.

References

Abdellaoui, M., Bleichrodt, H., & l’Haridon, O. (2013). Sign-dependence in intertemporal choice. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 47, 225–253.

Andreoni, J., & Sprenger, C. (2012a). Estimating time preferences from convex budgets. The American Economic Review, 102, 3333–3356.

Andreoni, J., & Sprenger, C. (2012b). Risk preferences are not time preferences. American Economic Review, 102, 3357–3376.

Augenblick, N., Niederle, M., & Sprenger, C. (2015). Working over time: Dynamic inconsistency in real effort tasks. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130, 1067–1115.

Baucells, M., & Heukamp, F. H. (2012). Probability and time trade-off. Management Science, 58, 831–842.

Benzion, U., Rapoport, A., & Yagil, J. (1989). Discount rates inferred from decisions: An experimental study. Management Science, 35, 270–284.

Bleichrodt, H., & Johannesson, M. (2001). Time preference for health: A test of stationarity versus decreasing timing aversion. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 45, 265–282.

Bleichrodt, H., Rohde, K. I., & Wakker, P. P. (2008). Koopmans’ constant discounting for intertemporal choice: A simplification and a generalization. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 52, 341–347.

Bleichrodt, H., Rohde, K. I., & Wakker, P. P. (2009). Non-hyperbolic time inconsistency. Games and Economic Behavior, 66, 27–38.

Bostic, R., Herrnstein, R. J., & Luce, R. D. (1990). The effect on the preference-reversal phenomenon of using choice indifferences. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 13, 193–212.

Brandts, J., & Cooper, D. J. (2006). A change would do you good.. An experimental study on how to overcome coordination failure in organizations. American Economic Review, 96, 669–693.

Caplin, A., & Leahy, J. (2004). The supply of information by a concerned expert. The Economic Journal, 114, 487–505.

Carlsson, F., He, H., Martinsson, P., Qin, P., & Sutter, M. (2012). Household decision making in rural China: Using experiments to estimate the influences of spouses. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 84(2), 525–536.

Casari, M., & Dragone, D. (2015). Choice reversal without temptation: A dynamic experiment on time preferences. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 50, 119–140.

Charness, G., & Rabin, M. (2002). Understanding social preferences with simple tests. Quarterly journal of Economics, 117(3), 817–869.

Charness, G., & Sutter, M. (2012). Groups make better self-interested decisions. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26, 157–176.

Coller, M., & Williams, M. B. (1999). Eliciting individual discount rates. Experimental Economics, 2, 107–127.

Cooper, D. J., & Kagel, J. H. (2005). Are two heads better than one? Team versus individual play in signaling games. American Economic Review, 95(33), 477–509.

DellaVigna, S. (2009). Psychology and economics: Evidence from the field. Journal of Economic Literature, 47, 315–372.

Denant-Boemont, L., & Loheac, Y. (2011). Time and teams: An experimental study about group inter-temporal choice. Working Paper.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2010). Are risk aversion and impatience related to cognitive ability? American Economic Review, 100, 1238–1260.

Epper, T., & Fehr-Duda, H. (2012). The missing link: Unifying risk taking and time discounting. Department of Economics, University of Zurich, Working Paper.

Epper, T., Fehr-Duda, H., & Bruhin, A. (2011). Viewing the future through a warped lens: Why uncertainty generates hyperbolic discounting. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 43, 169–203.

Fishburn, P. C., & Rubinstein, A. (1982). Time preference. International Economic Review, 23, 677–694.

Forsythe, R., Myerson, R. B., Rietz, T. A., & Weber, R. J. (1993). An experiment on coordination in multi-candidate elections: The importance of polls and election histories. Social Choice and Welfare, 10, 223–247.

Frederick, S. (2005). Cognitive reflection and decision making. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19, 25–42.

Frederick, S., Loewenstein, G., & O’donoghue, T. (2002). Time discounting and time preference: A critical review. Journal of economic literature, 40, 351–401.

Gerardi, D., & Yariv, L. (2007). Deliberative voting. Journal of Economic Theory, 134, 317–338.

Giné, X., Goldberg, J., Silverman, D., & Yang, D. (2014). Revising Commitments: Field evidence on the adjustment of prior choices. Working paper, World Bank.

Glaeser, E. L., & Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Extremism and social learning. Journal of Legal Analysis, 1, 263–324.

Goeree, J. K., & Yariv, L. (2011). An experimental study of collective deliberation. Econometrica, 79, 893–921.

Gollier, C., & Zeckhauser, R. (2005). Aggregation of heterogeneous time preferences. Journal of Political Economy, 113, 878–896.

Halevy, Y. (2008). Strotz meets Allais: Diminishing impatience and the certainty effect. American Economic Review, 98(3), 1145–1162.

Halevy, Y. (2015). Time consistency: Stationarity and time invariance. Econometrica, 83, 335–352.

Holcomb, J. H., & Nelson, P. S. (1992). Another experimental look at individual time preference. Rationality and Society, 4, 199–220.

Horowitz, J. K. (1992). A test of intertemporal consistency. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 17, 171–182.

Jackson, M., & Yariv, L. (2014). Present bias and collective dynamic choice in the lab. American Economic Review, 104, 4184–4204.

Jackson, M., & Yariv, L. (2015). Collective dynamic choice: The necessity of time inconsistency. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 7(4), 150–178.

Kang, M.-I., & Ikeda, S. (2014). Time discounting and smoking behavior: Evidence from a panel survey. Health Economics, 23, 1443–1464.

Kirby, K. N., & Maraković, N. N. (1995). Modeling myopic decisions: Evidence for hyperbolic delay-discounting within subjects and amounts. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 64, 22–30.

Loewenstein, G., & Prelec, D. (1992). Anomalies in intertemporal choice: Evidence and an interpretation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(2), 573–597.

Luhan, W. J., Kocher, M. G., & Sutter, M. (2009). Group polarization in the team dictator game reconsidered. Experimental Economics, 12, 26–41.

Maciejovsky, B., Sutter, M., Budescu, D. V., & Bernau, P. (2013). Teams make you smarter: How exposure to teams improves individual decisions in probability and reasoning tasks. Management Science, 59, 1255–1270.

Meier, S., & Sprenger, C. D. (2015). Temporal stability of time preferences. Review of Economics and Statistics, 97, 273–286.

Millner, A., & Heal, G. (2014). Resolving intertemporal conflicts: Economics vs Politics. Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Moscovici, S., & Zavalloni, M. (1969). The group as a polarizer of attitudes. Journal of personality and social psychology, 12, 125.

Myerson, R. B., & Weber, R. J. (1993). A theory of voting equilibria. American Political Science Review, 87(1), 102–114.

Noussair, C., Robin, S., & Ruffieux, B. (2004). Revealing consumers’ willingness-to-pay: A comparison of the BDM mechanism and the Vickrey auction. Journal of Economic Psychology, 25, 725–741.

Palfrey, T. R. (2009). Laboratory experiments in political economy. Annual Review of Political Science, 12, 379–388.

Perez-Arce, F. (2011). The effect of education on time preferences. Working paper, RAND Corporation.

Phelps, E. S., & Pollak, R. A. (1968). On second-best national saving and game-equilibrium growth. The Review of Economic Studies, 35(2), 185–199.

Plott, C. R. (1967). A notion of equilibrium and its possibility under majority rule. The American Economic Review, 57(4), 787–806.

Read, D., Frederick, S., & Airoldi, M. (2012). Four days later in Cincinnati: Longitudinal tests of hyperbolic discounting. Acta Psychologica, 140, 177–185.

Robson, A. J., & Szentes, B. (2014). A biological theory of social discounting. American Economic Review, 104, 3481–3497.

Rohde, K. I. (2010). The hyperbolic factor: A measure of time inconsistency. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 41, 125–140.

Samuelson, P. A. (1937). A note on measurement of utility. The Review of Economic Studies, 4, 155–161.

Sayman, S., & Öncüler, A. (2009). An investigation of time inconsistency. Management Science, 55, 470–482.

Schaner, S. (2015). Do opposites detract? Intrahousehold preference heterogeneity and inefficient strategic savings. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7, 135–174.

Schkade, D., Sunstein, C. R., & Kahneman, D. (2000). Deliberating about dollars: The severity shift. Columbia Law Review, 100, 1139–1175.

Schram, A. J. (2004). Experimental public choice. Berlin: Springer.

Shapiro, J. (2010). Discounting for you, me, and we: Time preference in groups and pairs. Working paper.

Sobel, J. (2014). On the relationship between individual and group decisions. Theoretical Economics, 9, 163–185.

Stoner, J. A. (1968). Risky and cautious shifts in group decisions: The influence of widely held values. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 4, 442–459.

Strotz, R. H. (1955). Myopia and inconsistency in dynamic utility maximization. The Review of Economic Studies, 23, 165–180.

Takeuchi, K. (2011). Non-parametric test of time consistency: Present bias and future bias. Games and Economic Behavior, 71, 456–478.

Thaler, R. (1981). Some empirical evidence on dynamic inconsistency. Economics Letters, 8, 201–207.

Viscusi, W. K., Phillips, O. R., & Kroll, S. (2011). Risky investment decisions: How are individuals influenced by their groups? Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 43, 81–106.

Wölbert, E., & Riedl, A. (2013). Measuring time and risk preferences: Reliability, stability, domain specificity. CESifo working paper no 4339.

Zuber, S. (2010). The aggregation of preferences: Can we ignore the past? Theory and Decision, 70, 367–384.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We thank Aurelien Baillon, Nicolas Houy, Vincent Merlin, Amnon Rapoport, Jeeva Somasundaram, Karine Van Der Straeten, Marie-Claire Villeval, Peter Wakker, the editor of this journal as well as two anonymous referees for helpful comments. We also thank Elven Priour for programming the script and organizing the sessions.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Indexes

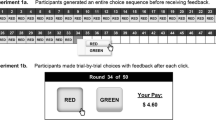

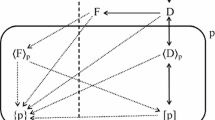

This appendix reports values of the indexes of violation of stationarity (Tables 4, 5, 6), dynamic consistency (Fig. 4), and age independence (Fig. 5).

Appendix 2: Results for the additional treatments

For the Repetition treatment, a decision maker was classified as impatient (resp. patient) if at least four of six indifference values yielded an impatient (resp. patient) answer; otherwise, the decision maker was classified as mixed. For the remaining additional treatments (Voting treatment, Informed planner treatment, Uninformed planner treatment), a decision maker was classified as impatient (patient) if at least two out of three indifference values yielded an impatient (patient) answer. The classifications are presented in Table 7. Tables 8, 9, 10 and 11 report additional results on stationarity, dynamic consistency, age independence, shape of impatience and distance to individual preferences.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Denant-Boemont, L., Diecidue, E. & l’Haridon, O. Patience and time consistency in collective decisions. Exp Econ 20, 181–208 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-016-9481-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-016-9481-4