Abstract

Climate change has become a serious threat for crop productivity worldwide. The increased frequency of heat waves strongly affects reproductive success and thus yield for many crop species, implying that breeding for thermotolerant cultivars is critical for food security. Insight into the genetic architecture of reproductive heat tolerance contributes to our fundamental understanding of the stress sensitivity of this process and at the same time may have applied value. In the case of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), germplasm screenings for thermotolerance have often used yield as the main measured trait. However, due to the complex nature of yield and the relatively narrow genetic variation present in the cultivated germplasm screened, there has been limited progress in understanding the genetic basis of reproductive heat tolerance. Extending the screening to wild accessions of related species that cover a range of climatic conditions might be an effective approach to find novel, more tolerant genetic resources. The purpose of this study was to provide insight into the sensitivity of individual reproductive key traits (i.e. the number of pollen per flower, pollen viability and style protrusion) to heat-wave like long-term mild heat (LTMH), and determine the extent to which genetic variation exists for these traits among wild tomato species. We found that these traits were highly variable among the screened accessions. Although no overall thermotolerant species were identified, several S. pimpinellifolium individuals outperformed the best performing cultivar in terms of pollen viability under LTMH. Furthermore, we reveal that there has been local adaptation of reproductive heat tolerance, as accessions from lower elevations and higher annual temperature are more likely to show high pollen viability under LTMH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ambient temperatures are rising as part of the current global climate change, threatening agricultural output (IPCC 2007, 2013). High temperatures cause morphological, physiological, biochemical and molecular changes in plants that affect growth, and is particularly detrimental during the reproductive stages (Wahid et al. 2007). This leads to reduced yields in crop species, and thus has a large impact on global food production (Barnabás et al. 2008; Hedhly et al. 2009). For example, during cultivation, tomato is often exposed to high temperature either in the greenhouse or in the field, and consequently, fruit set is reduced in many S. lycopersicum cultivars.

Exploration of natural variation may offer insight into the genetics of stress tolerance, and can provide genetic diversity useful for breeding (Grandillo et al. 2011). This also applies to reproductive heat tolerance, but so far, screening for variation in tomato heat sensitivity has yielded only a few genotypes considered to be thermotolerant (Opena et al. 1992), and these have limited applicability for pre-breeding (Grilli et al. 2007). There seem to be at least two major reasons for this. Firstly, in previous germplasm screenings fruit set was the main trait of interest. However, fruit set is a complex trait, i.e. it represents the sum of multiple sub-traits (yield components). Thus, there may be a relatively small chance that optimal sub-traits combine to generate a strongly outperforming genotype. Furthermore, the complexity of the relation among different traits involved in fruit set complicates genetic analysis. As an alternative approach, it might be more effective to analyse the various contributing sub-traits individually and combine them afterwards in a breeding context. For example, decreases in tomato fruit set under long-term mildly elevated temperatures has been shown to correlate with a decrease in pollen viability (Dane et al. 1991; Firon et al. 2006; Kinet and Peet 1997; Levy et al. 1978; Peet et al. 1998; Pressman 2002; Pressman et al. 2006; Sato et al. 2000, 2006; Xu et al. 2017b). Also, style protrusion may affect reproductive success under high temperature (Charles and Harris 1972; Dane et al. 1991; Rick and Dempsey 1969; Rudich et al. 1977; Saeed et al. 2007; Xu et al. 2017b). Investigation of these traits separately might provide a more effective strategy to determine the genetic basis of reproductive thermotolerance under long-term mild heat (LTMH).

Secondly, germplasm used in thermotolerance screening has mainly consisted of S. lycopersicum cultivars (Abdul-Baki and Stommel 1995; Dane et al. 1991; Grilli et al. 2007; Kugblenu et al. 2013a; Opena et al. 1992). However, as a result of domestication and intensive breeding, the cultivated tomato germplasm has a rather narrow genetic base (Bergougnoux 2014), meaning that only a subset of the genes and alleles available in the wild progenitor gene pool are still present among crop cultivars (Godfray et al. 2010; Ladizinsky 1985; Olsen and Wendel 2013). Especially, as breeding efforts have mainly targeted yield at more or less optimal cultivation conditions, it seems likely that abiotic stress tolerance traits have been lost (Ladizinsky 1985; Paran and Van Der Knaap 2007). This implies that the potential gain in heat tolerance level from cultivated germplasm is likely to be limited. A broader genetic diversity can be found in species related to tomato, and could serve as an alternative source of plant thermotolerance traits (Víquez-Zamora et al. 2013). Wild tomato species are found in a variety of habitats ranging from sea level to above 3000 m in altitude and from temperate deserts to wet tropical rainforests, and thus face a range of environmental challenges. As a result of natural selection, these wild species vary broadly in terms of morphology, physiology, biochemistry and stress tolerance levels (Dolferus 2014; Grandillo et al. 2011; Maduraimuthu and Prasad 2014). There is also variation in mating systems among wild accessions, i.e. self-compatible (SC) versus self-incompatible (SI), which is likely to affect reproductive traits and putatively their performance under LTMH (Arroyo 1973; Baker 1955; Cruden 1977; Georgiady and Lord 2002; Peralta et al. 2008).

Here, we hypothesised that higher levels of reproductive thermotolerance are present in wild relatives of tomato than in the cultivated tomato germplasm. We investigated the performance of 64 accessions across 13 wild species and 7 S. lycopersicum cultivars, including a subset known for relatively good reproductive thermotolerance under control temperature and long-term mild heat. We focused on reproductive traits generally assumed to contribute to overall fertility, i.e. the number of pollen per flower, pollen viability and the distance between the top of the anther and the stigma (style protrusion). In addition, we tested whether the mating system influenced these traits under LTMH, and determined whether local adaption to thermotolerance had occurred.

Materials and methods

Plant material and screening procedure

Sixty-four accessions belonging to 13 wild species (S. arcanum, S. cheesmaniae, S. chilense, S. chmielewskii, S. corneliomulleri, S. galapagense, S. habrochaites, S. huaylasense, S. lycopersicum, S. neorickii, S. pennellii, S. peruvianum and S. pimpinellifolium) and 7 S. lycopersicum cultivars (“Hotset”, “Malintka101”, “Moneyberg”, “Nagcarlang”, “NCHS-1”, “Saladette” and “Tof Hamlet”) were obtained from various sources (Table S1). Seeds were incubated in 2.5% hypochlorite for 30 min at room temperature to improve germination and reduce pathogen load (Rick and Borgino, TGRC, http://tgrc.ucdavis.edu/seed_germ.aspx), followed by germination on potting soil (Horticoop, Lentse Potgrond, Slingerland Potgrond) covered with vermiculite (Agra-Vermiculite) under standard greenhouse conditions. Seedlings were transferred to 0.5 L pots after 2 weeks and, after 1 month, placed in 12 L pots, containing potting soil and 4 g L−1 Osmocote® Exact Standard 3–4 M (Everris). When the transition from the vegetative to the generative phase occurred, flower buds were removed and the plants were transferred to a climate chamber maintaining a 14/10 h day/night photoperiod (~ 300 µmol s−1 m−2 at plant height; Philips D-Papillon daylight spectrum 340 W lamps and Philips MastergreenPower TLD58 W/840 fluorescent tubes) and humidity of 70–80% at either control temperature of 25/19 °C (CT) or long-term mild heat of 32/26 °C (LTMH) for at least 14 days. Plants were grown and analysed in a staggered manner over a time course of 4 months in batches of 15 individuals, with complete randomisation of accessions. To determine the influence of the genotype on the studied traits, cuttings were taken from several plants. In order to set roots, the cuttings were put in potting soil (Horticoop, Lentse Potgrond, Slingerland Potgrond) and kept in the greenhouse in a plastic container to maintain a high humidity. After 2 weeks, cuttings were placed in 12 L pots, containing potting soil and 4 g L−1 Osmocote® Exact Standard 3–4 M (Everris). When the transition from the vegetative to the generative phase occurred, flower buds were removed and the cuttings were treated similarly as the mother plants.

Phenotypic assessment

To determine pollen quality, anthers of the three most recently opened flowers were cut into 4 equal transverse sections. After addition of 200 µL peroxidase indicator (Rodriguez-Riano and Dafni 2000) consisting of 1 vial peroxidase indicator (Sigma 3901-10VL) in 0.012% (v/v) H2O2 and 10% (v/v) Trizmal buffer (903C; Sigma–Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). Pollen were considered viable when roundly shaped and stained dark. In order to determine the pollen viability (PV, in %), 100 pollen were assessed per flower. To determine the number of pollen per flower (PN) the number of pollen was counted in 25 chambers (0.04 mm2) of a haemocytometer. In addition, style protrusion (SP in mm) was measured. For PN, PV and SP, three flowers were analysed per plant.

Climate data

Climatic data sets for the earth land surface area were downloaded from CHELSA (Karger et al. 2017). Using the R package “raster” version 2.5–8 (Hijmans and van Etten 2012), all 19 bioclimatic variable data (BIO1 to BIO19) were extracted for the period 1979-2013 for each accession according to the GPS coordinates of the original collection site (Table S1).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using transformed data, value’ = 10Log(value+1), except for PV, to which a logit transformation was applied, value’ = LN((value+1)/(101-value)). The relation between traits was determined by a Pearson correlation analysis. To assess the heritability of the traits, a Pearson correlation analysis of the means of clones (cuttings) and their corresponding mother plant were performed using a paired sample correlation analysis. Broad-sense heritability was calculated for PN and PV by dividing the variance among clones by the total variance among and within clones (i.e. variance among clones/total variance). To test for variation in heat tolerance among species, a two-way ANOVA was performed at species level (using mean values of accessions and temperature treatment). Differences in performance under LTMH between species (using mean values of accessions) were assessed by a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD as post hoc test. At accession level (using mean values of plants), differences between accessions within species were assessed by a one-way ANOVA using Tukey’s HSD as post hoc test. For PN and PV, the wild accessions were compared to the best tomato cultivar by a one-way ANOVA with LSD post hoc test. To test whether the best performing genotypes from the best wild accession outperformed Nagcarlang, a one-way ANOVA with LSD post hoc test was performed, using clones as replicates. To analyse the effect of temperature treatment and mating system, a two-way ANOVA with temperature treatment and mating system class variables was performed. The different geographical characteristics were correlated with the physiological plant traits under LTMH by Pearson correlation analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 21.

Results

To assess reproductive performance under long-term mild heat (LTMH) in the wild tomato germplasm, 64 wild accessions belonging to 13 wild species and 7 S. lycopersicum cultivars were screened. Accessions were selected to roughly encompass the spatial and elevation distribution of accessions of each species, and where possible, including accessions with annotations related to high temperature or other abiotic stresses (Table S1). None of the wild accessions screened in this study were previously determined to be heat tolerant. In total, 201 and 317 plants were exposed to control (CT) or LTMH conditions, respectively, and three reproductive traits, the number of pollen per flower (PN), pollen viability (PV) and style protrusion (SP), were analysed.

Trait heritability and inter-trait relations

To determine the influence of genotype on the selected traits, cuttings from several individuals were grown and exposed to LTMH. Significant correlations between mother plants and cuttings were detected for all traits (Fig. 1). The division of the variance among clones by the total variance among and within clones of PN and PV measurements of the cuttings revealed a broad-sense heritability of 0.78 and 0.85, respectively (Table 1).

Correlations of traits between mother plant and cuttings under long-term mild heat. Mother plants of 4 accessions (from S. corneliomulleri, S. peruvianum, S. pimpinellifolium and S. pennellii) and two tomato cultivars (Moneyberg and Nagcarlang) were selected based on their difference in pollen viability under LTMH. Cuttings were generated and phenotyped under LTMH for a The number of pollen per flower (*1000), b pollen viability (%), and c style protrusion (mm). Trait values for the cuttings represent the average (n = 2–15). The Pearson’s correlation coefficient is given in each graph (r). Significance level (two-tailed): *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

To evaluate relationships between the traits of interest, Pearson correlation analyses between the trait means per species were performed. In addition, to correct for putative species-specific effects, a between-species Pearson correlation analysis was performed. In both cases, no significant correlations were detected (Table 2; data not shown). In addition, when considering all accessions as independent (n = 71), no significant correlations were detected between any of the traits under CT and LTMH (data not shown). Together, this suggests that the three traits under study are largely independently inherited in these species and accessions.

Variation in the number of pollen per flower under LTMH

Temperature treatment and species both had a significant effect on the number of pollen per flower (PN), and no interaction was found between them (Table 3). Exposure to LTMH reduced PN by 76.3% on average. PN of S. corneliomulleri was significantly higher than that of S. chmielewskii, which had the lowest PN under LTMH (Table S2). For the S. chilense, S. chmielewskii, S. galapagense, S. huaylasense, S. pennellii, S. peruvianum and S. lycopersicum cultivars, significant differences in PN among accessions within the species were detected under LTMH (Table S3). However, none of the wild accessions performed better, i.e. had a significantly higher PN, than the best performing cultivar, NCHS-1 (Fig. 2a; Table S3).

Cultivars and the three best performing wild accessions with respect to pollen number per flower and pollen viability under long-term mild heat. a Pollen number per flower (PN), and b pollen viability (PV). Box of boxplot represents the interquartile range (IQR), with indication of the median. Lower and upper whiskers represent the smallest and largest observations smaller than or equal to lower and upper hinge ± 1.5 * IQR, respectively. Each dot represents an individual plant

Variation in pollen viability under LTMH

In response to LTMH, PV was reduced by 85.6% on average, at the species level. No significant differences were detected between any of the screened species, nor was there a significant interactive effect between species and treatment (Table 3). Within S. corneliomulleri, S. neorickii, S. pimpinellifolium and the S. lycopersicum cultivars, significant differences were detected among accessions (Table S3). However, also for this trait, none of the wild accession performed better under LTMH, i.e. had a significant higher PV, than the best performing cultivar, Nagcarlang (Fig. 2b; Table S3). As wild accessions may exhibit genotypic diversity, we tested whether the best performing genotypes from the best wild accession (S. pimpinellifolium LA1630) outperformed Nagcarlang, using multiple clones per genotype. Indeed, four of the five tested genotypes had significantly higher PV under LMTH than Nagcarlang (Fig. 3).

Variation in style protrusion under LTMH

SP was significantly increased by LTMH, and differed significantly among species, but no interactive effect between temperature treatment and species was detected, indicating that the different species respond similarly to LTMH with respect to SP (Table 3 and Table S2). Within species, significant differences under LTMH were observed only in the cases of S. pimpinellifolium and the tomato cultivars (Table S3). None of the wild accessions outperformed the cultivars under LTMH (i.e. had lower SP), as cultivar Saladette did not show any protrusion (Table S3). Many wild accessions had higher SP then the cultivars, already under control temperature.

Comparison between self-compatible and self-incompatible accessions

To test the effect of an accession’s mating system on reproductive traits, self-compatible (SC) and self-incompatible (SI) accessions were compared. SI accessions had significantly higher PN and SP than SC accessions under both temperature treatments (Fig. 4). None of the traits showed significant interaction between the two factors.

Trait values in self-compatible and self-incompatible accession under control and long-term mild heat. To compare genotypes, multiple cuttings per genotype were evaluated. Values represent the mean ± standard deviation (n = 5–20 plants). Differences were assessed by a one-way ANOVA followed by LSD post hoc test. Asterisks above the bars indicate a significant difference between the respective genotype and the cultivar Nagcarlang. Significance level: *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001, n.s., not significant. a Number of pollen number per flower (PN), b pollen viability (PV), and c style protrusion (SP). SC self-compatible, SI self-incompatible, CT control temperature, LTMH long-term mild heat. Values represent the mean ± standard deviation (n = 33 and 37 for SI and SC accessions, respectively). Significance of treatment/mating system/interaction was determined by a two-way ANOVA: ***P < 0.001; n.s., not significant

Relationship between trait performance and climatic parameters at site of origin

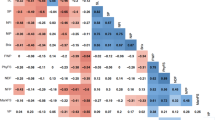

Due to the wide variation in geographical origin of the accessions, ranging from a latitude of − 24.211 to 0.867, longitude of − 91.417 to − 43.083, and elevation from 0 up to 3450 meters above sea level (Fig. 5), accessions habitats were also diverse and varied from very dry to wet locations and from sandy coastal areas to high up in the mountains. To assess whether adaptation to local conditions had occurred, a Pearson correlation analysis between the phenotypic data and various geographical and climatic parameters was performed. A significant negative correlation was found between the accessions’ PV and the elevation at the site of origin (Table 4). A significant positive correlation was found with the annual mean temperature, and the same trend was visible for related temperature parameters (Table S4). Thus, accessions derived from lower elevations and warmer climates are more likely to be tolerant to LTMH with respect to PV.

Discussion

The reduction in tomato yield under long-term mild heat (LTMH) may be attributed to the plant’s vulnerability during reproductive development, resulting in a lower number of pollen per flower (PN) and pollen viability (PV) (Dane et al. 1991; Firon et al. 2006; Kinet and Peet 1997; Levy et al. 1978; Peet et al. 1998; Pressman 2002; Pressman et al. 2006; Sato et al. 2000, 2006; Xu et al. 2017b). In this study, we analysed the natural variation of reproductive thermotolerance in wild tomato species, which may serve as gene sources for cultivated tomato.

Superior heat tolerant wild genotypes with regard to pollen viability

Yield screenings of cultivated S. lycopersicum under high temperatures have shown phenotypic variation, but only a few cultivars, including Nagcarlang, Hotset and Saladette seem to perform relatively well under such conditions (Abdul-Baki and Stommel 1995; Dane et al. 1991; Kugblenu et al. 2013b; Levy et al. 1978; Rudich et al. 1977; Villareal et al. 1978; Xu et al. 2017b). Indeed, the Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center (AVRDC; now World Vegetable Center) concluded from screenings of > 4000 wild and cultivated accessions under hot conditions that less than 1% could be considered highly heat tolerant for fruit set (Opena et al. 1992; Villareal et al. 1978). Fruit set under high temperature has been reported to have low narrow-sense heritability (El Ahmadi and Stevens 1979; Hanson et al. 2002; Villareal et al. 1978). However, it is a complex trait, and higher heritability may be found by separating the underlying individual key traits affecting fruit set. Indeed, we have recently reported two major QTLs for PN and PV in an S. lycopersicum mapping population (Xu et al. 2017a). In the current study, screening of clones of individuals for PN and PV under LTMH in climate chambers indicated that a large fraction of the total phenotypic variance was explained by the genetic variance. Whether these sub-traits also express in other genetic backgrounds and environmental conditions, such as field conditions, remains to be determined.

Our study did not detect overall thermotolerance of yield-contributing sub-traits in wild species compared to the performance of cultivars, but we show that several genotypes from the accession LA1630 outperform the best performing cultivar in terms of PV under LTMH. Given the previously reported correlation between PV and fruit set under LTMH (e.g. Dane et al. 1991; Sato et al. 2000; Xu et al. 2017b), we conclude that wild germplasm might indeed be a valuable resource to enrich domesticated germplasm for reproductive thermotolerance.

Mating system advantages under LTMH

In the tomato clade, the mating system ranges between self-incompatible (SI) to self-compatible (SC) crossers (Miller and Tanksley 1990; Rick et al. 1977). In general, flowers of SI plant species produce more pollen than closely related SC species, probably because a much smaller fraction of the pollen will reach a compatible stigma in the case of SI (Arroyo 1973; Baker 1955; Cruden 1977; Georgiady and Lord 2002). Indeed, this study indicated that PN was significantly higher in SI compared to SC accessions. Importantly, no interaction with temperature treatment was found. Thus, SI accessions seem to be a good source for a high PN under LTMH and could be interesting for thermotolerance breeding purposes. In contrast to PN, PV was not significantly different between the mating types in either temperature treatment.

Several studies indicated that protrusion of the style from the antheridial cone of > 1 mm prevents fruit set from self-fertilisation (Dane et al. 1991; Rudich et al. 1977; Saeed et al. 2007). As reported previously (Grandillo et al. 2011; Peralta et al. 2008), SP was reduced in SC accessions and almost absent in some cultivars, probably due to strong trait selection. SP was enhanced under high temperature, and although SC accessions still showed less protrusion of the style in LTMH, in many accessions the distance between anther and style was likely too large to allow self-pollination. The tomato cultivars performed relatively well for SP, suggesting wild relatives are less useful for improving this trait.

By enhancing SP under high temperature, SC plants seem to mimic the constitutive SI phenotype. Stimulating cross-pollination under LTMH via increased SP, and lower PN and PV, might increase the chance that SC individuals are fertilised by another plant. This fits with the idea that genetic recombination may be beneficial under stress conditions, allowing the creation of more adapted genotypes (Hedhly et al. 2004; Müller and Rieu 2016).

Local adaptation

Wild tomatoes occur over a wide range of ecological and climatic conditions, but individual species and accessions are often adapted to particular microclimates (Bauchet and Causse 2012; Zuriaga et al. 2009). The diversity of conditions is expressed at the morphological, physiological, sexual and molecular levels (Bauchet and Causse 2012; Peralta and Spooner 2005). We explored whether variation in environment at the sites of origin of accessions has resulted in variation in thermotolerance and found that the mean PV of accessions correlated negatively with elevation. In line with our results, chilling tolerance in tomato has also been shown to correlate with elevation: for geographical populations of L. hirsutum (S. habrochaites), chilling tolerance, including traits such as seedling survival rate and pollen tube growth, was greatest in those derived from the higher elevations (Patterson et al. 1978; Zamir et al. 1981). It seems likely that the effects of elevation are mainly due to local temperature profiles. Indeed, we found that temperature variables such as mean annual temperature correlated positively to PV under LTMH. Similarly, seedling survival and root growth at high temperature for natural populations of Arabidopsis thaliana correlated to temperature parameters at the site of origin (Zhang et al. 2015). In rice, the presence of a major quantitative trait locus (QTL) for thermotolerance, TT1, has also been linked to the local temperature profile (Li et al. 2015). Such local adaptation may also be seen at the molecular level, as the heat stress response of Arabidopsis and Chenopodium album accessions, as measured by induction of heat shock proteins, was more strongly induced in accessions originating from cooler rather than warmer environments (Barua et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2015).

Conclusion

We conclude that PN and PV are variable among wild and cultivated tomato accessions, and that this variation is adaptive to the local environment in the case of PV. The absence of overall thermotolerant accessions with regards to PV suggests that selective pressure is not very strong, or that there is a trade-off with an unknown, beneficial trait. Although the best performing wild accessions were equally thermotolerant to the best performing cultivars in terms of PN and PV, the genetic background of these traits in the wild accessions may be novel and could thus be valuable for thermotolerance breeding of tomato, especially if the traits show additivity. In the case of PV, several outperforming individuals were identified. Interspecific QTL analysis with S. lycopersicum would be a logical step towards characterisation and application of the traits. Phenotypic improvement from QTLs depend on unpredictable interactions with the genetic background, probably because variation often involves additional, undetected small-effect loci (Mackay et al. 2009). Moreover, for successful application, it will be important to consider the environmental context dependency of the expression of QTLs (Collins et al. 2008). In the end, reproductive success depends on multiple traits and we hypothesize that combining optimal variants of all these traits will be needed to significantly improve tolerance of reproduction to LTMH. Traits may be transferred and stacked through marker assisted breeding or by application of newly developed genetic modification methods (Sander and Joung 2014; Woo et al. 2015).

References

Abdul-Baki AA, Stommel JR (1995) Pollen viability and fruit set of tomato genotypes under optimum- and high-temperature regimes. HortScience 30:115–117

Arroyo MTK (1973) Chiasma frequency evidence on the evolution of autogamy in Limnanthes floccosa. Evolution 27(4):679–688

Baker HG (1955) Self-compatibility and establishment after “long-distance” dispersal. Evolution 9(3):347–349

Barnabás B, Jäger K, Fehér A (2008) The effect of drought and heat stress on reproductive processes in cereals. Plant, Cell Environ 31:11–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01727.x

Barua D, Heckathorn SA, Coleman JS (2008) Variation in heat-shock proteins and photosynthetic thermotolerance among natural populations of Chenopodium album L. from contrasting thermal environments: implications for plant responses to global warming. J Integr Plant Biol 50:1440–1451. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00756.x

Bauchet G, Causse M (2012) “Genetic Diversity in Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) and its Wild Relatives,”. In: M Çalişkan (ed) Genetic diversity in plants, pp 133–162

Bergougnoux V (2014) The history of tomato: from domestication to biopharming. Biotechnol Adv 32:170–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.11.003

Charles WB, Harris RE (1972) Tomato fruit-set at high and low temperatures. Can J Plant Sci 111:461–476

Collins NC, Tardieu F, Tuberosa R (2008) Quantitative trait loci and crop performance under abiotic stress: where do we stand? Plant Physiol 147:469–486. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.108.118117

Cruden RW (1977) Pollen-ovule ratios: a conservative indicator of breeding systems in flowering plants. Evolution 31(1):32–46

Dane F, Hunter AG, Chambliss OL (1991) Fruit set, pollen fertility, and combining ability of selected tomato genotypes under high temperature field conditions. J Am Soc Hortic Sci 116:906–910

Dolferus R (2014) To grow or not to grow: a stressful decision for plants. Plant Sci 229:247–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.10.002

El Ahmadi A, Stevens M (1979) Reproductive responses of heat-tolerant tomatoes to high temperatures. J Am Soc Hortic Sci 104:686–691

Firon N, Shaked R, Peet MM, Pharr DM, Zamski E (2006) Pollen grains of heat tolerant tomato cultivars retain higher carbohydrate concentration under heat stress conditions. Sci Hortic 109:212–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2006.03.007

Georgiady MS, Lord EM (2002) Evolution of the Inbred Flower Form in the Currant Tomato Lycopersicon pimpinellifolium. Int J Plant Sci 163:531–541. https://doi.org/10.1086/340542

Godfray C, Beddington J, Crute I, Haddad L, Lawrence D, Muir JF et al (2010) Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 327(5967):812–818

Grandillo S, Chetelat R, Knapp S, Spooner D, Peralta I, Cammareri M et al. (2011) “Solanum sect. Lycopersicon”. In: C Kole (ed) Wild crop relatives: genomic and breeding resources vegetables, Springer, Heidelberg, pp 129–216 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-20450-09

Grilli GVG, Braz LT, Gertrudes E, Lemos M (2007) QTL identification for tolerance to fruit set in tomato by fAFLP markers. Crop Breed Appl Biotechnol 7:234–241

Hanson PM, Chen J, Kuo G (2002) Gene action and heritability of high-temperature fruit set in tomato line CL5915. HortScience 37:172–175

Hedhly A, Hormaza JI, Herrero M (2004) Effect of temperature on pollen tube kinetics and dynamics in sweet cherry, Prunus avium (Rosaceae). Am J Bot 91:558–564. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.91.4.558

Hedhly A, Hormaza JI, Herrero M (2009) Global warming and sexual plant reproduction. Trends Plant Sci 14:30–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2008.11.001

Hijmans RJ, van Etten J (2012) Raster: geographic analysis and modeling with raster data. http://cran.r-project.org/package=raster

IPCC (2007) Climate change 2007: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Solomon S, Qin D, Manning M, Alley RB, Berntsen T, Bindoff NL, Chen ZC. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/publications_ipcc_fourth_assessment_report_wg1_report_the_physical_science_basis.htm

IPCC (2013) Summary for policymakers climate change 2013: the physical science basis contribution of working group I to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change, Stocker TF, Qin D, Plattner GK, Tignor M, Allen SK, Boschung J, Naue A. Cambridge and New York. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/

Karger DN, Conrad O, Böhner J, Kawohl T, Kreft H, Soria-Auza RW et al (2017) Climatologies at high resolution for the earth’s land surface areas. Sci. Data 4:170122. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.122

Kinet JM, Peet MM (1997) Tomato. The physiology of vegetable crops (Commonwealth Agricultural Bureau (CAB) international. Wallingford, UK), pp 207–258

Kugblenu YO, Oppong Danso E, Ofori K, Andersen MN, Abenney-Mickson S, Sabi E et al (2013a) Screening tomato genotypes in Ghana for adaptation to high temperature. Acta Agric Scand Sect B—Soil Plant Sci 63:516–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/09064710.2013.813062

Kugblenu YO, Oppong Danso E, Ofori K, Andersen MN, Abenney-Mickson S, Sabi EB et al (2013b) Screening tomato genotypes for adaptation to high temperature in West Africa. Acta Agric Scand Sect B—Soil Plant Sci 63:516–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/09064710.2013.813062

Ladizinsky G (1985) Founder effect in crop-plant evolution. Ecomonic Bot 39:191–199

Levy A, Rabinowitch HD, Kedar N (1978) Morphological and physiological characters affecting flower drop and fruit set of tomatoes at high temperatures. Euphytica 27:211–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00039137

Li X-M, Chao D-Y, Wu Y, Huang X, Chen K, Cui L-G et al (2015) Natural alleles of a proteasome α2 subunit gene contribute to thermotolerance and adaptation of African rice. Nat Genet 47:827–833. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3305

Mackay TFC, Stone EA, Ayroles JF (2009) The genetics of quantitative traits: challenges and prospects. Nat Rev Genet 10:565–577. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2612

Maduraimuthu D, Prasad PVV (2014) “High Temperature Stress,”. In: Jackson M, Ford-Lloyd BV, Perry ML (eds) Plant genetic resources and climate change, (CABI), pp 201–220

Miller JC, Tanksley SD (1990) RFLP analysis of phylogenetic relationships and genetic variation in the genus Lycopersicon. Theor Appl Genet 80:437–448

Müller F, Rieu I (2016) Acclimation to high temperature during pollen development. Plant Reprod 29:107–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00497-016-0282-x

Olsen KM, Wendel JF (2013) A bountiful harvest: genomic insights into crop domestication phenotypes. Annu Rev Plant Biol 64:47–70. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120048

Opena RT, Chen JT, Kuo GT, Chen HM (1992) Genetic and Physiological Aspects of Tropical Adaptation in Tomato. Adaptation of food crops to temperature and water stress. Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center, Shanua, pp 257–270

Paran I, Van Der Knaap E (2007) Genetic and molecular regulation of fruit and plant domestication traits in tomato and pepper. J Exp Bot 58:3841–3852. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erm257

Patterson B, Paull R, Smillie R (1978) Chilling Resistance in Lycopersicon hirsutum humb. & bonpl., a wild tomato with a wild altitudinal distribution. Aust J Plant Physiol 5:609–617

Peet MM, Sato S, Gardner RG (1998) Comparing heat stress effects on male-fertile and male-sterile tomatoes. Plant, Cell Environ 21:225–231

Peralta IE, Spooner DM (2005) Morphological characterization and relationships of wild tomatoes (Solanum L. sect. Lycopersicon). A Festschrift William G. D’Arcy 104:227–257

Peralta IE, Spooner DM, Knapp S (2008) “Taxonomy of wild tomatoes and their relatives (Solanum sect. Lycopersicoides, sect. Juglandifolia, sect. Lycopersicon; Solanaceae),”. In: Anderson C (ed) Systematic botany monographs, (The American Society of Plant Taxonomists), 1–186 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.113.2935.3.

Pressman E (2002) The effect of heat stress on tomato pollen characteristics is associated with changes in carbohydrate concentration in the developing anthers. Ann Bot 90:631–636. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcf240

Pressman E, Harel D, Zamski E, Shaked R, Althan L, Rosenfeld K et al (2006) The effect of high temperatures on the expression and activity of sucrose-cleaving enzymes during tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) anther development. J Hortic Sci Biotechnol 81:341–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/14620316.2006.11512071

Rick CM, Dempsey WH (1969) Position of the stigma in relation to fruit setting of the tomato. Bot Gaz 130:180–186. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2474143.

Rick C, Fobes J, Holle M (1977) Genetic variation in Lycopersicon pimpinellifolium: evidence of evolutionary change in mating systems. Plant Syst Evol 127:139–170. papers://cc1b5c7f-a7db-41a0-b721-8bdfaf6a062e/Paper/p57

Rodriguez-Riano T, Dafni A (2000) A new procedure to asses pollen viability. Sex Plant Reprod 12:241–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004970050008

Rudich J, Zamski E, Regev Y (1977) Genotypic variation for sensitivity to high temperature in the tomato: pollination and fruit set. Botanical Gazette 138:448–452

Saeed A, Hayat K, Khan AA, Iqbal S (2007) Heat tolerance studies in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). Int J Agric Biol 9:649–652 http://www.fspublishers.org

Sander JD, Joung JK (2014) CRISPR-Cas systems for editing, regulating and targeting genomes. Nat Biotechnol 32:347–355. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2842

Sato S, Peet MM, Thomas JF (2000) Physiological factors limit fruit set of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) under chronic, mild heat stress. Plant, Cell Environ 23:719–726. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3040.2000.00589.x

Sato S, Kamiyama M, Iwata T, Makita N, Furukawa H, Ikeda H (2006) Moderate increase of mean daily temperature adversely affects fruit set of Lycopersicon esculentum by disrupting specific physiological processes in male reproductive development. Ann Bot 97:731–738. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcl037

Villareal RL, Lai SH, Wong SH (1978) Screening for heat tolerance in the genus Lycopersicon. HortScience 13:479–481

Víquez-Zamora M, Vosman B, van de Geest H, Bovy A, Visser RGF, Finkers R et al (2013) Tomato breeding in the genomics era: insights from a SNP array. BMC Genomics 14:354. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-14-354

Wahid A, Gelani S, Ashraf M, Foolad M (2007) Heat tolerance in plants: an overview. Environ Exp Bot 61:199–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2007.05.011

Woo JW, Kim J, Kwon S Il, Corvalán C, Cho SW, Kim H et al (2015) DNA-free genome editing in plants with preassembled CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Nat Biotechnol 33:1162–1164. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3389

Xu J, Driedonks N, Rutten MJM, Vriezen WH, de Boer G-J, Rieu I (2017a) Mapping quantitative trait loci for heat tolerance of reproductive traits in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Mol Breed 37:37–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11032-017-0664-2

Xu J, Wolters-Arts M, Mariani C, Heidrun H, Rieu I (2017b) Heat stress affects vegetative and reproductive performance and trait correlations in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Euphytica 213:156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-017-1949-6

Zamir D, Tanksley SD, Jones RA (1981) Low temperature effect on selective fertilization by pollen mixtures of wild and cultivated tomato species. Theor Appl Genet 59:235–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00265501

Zhang N, Belsterling B, Raszewski J, Tonsor SJ (2015) Natural populations of Arabidopsis thaliana differ in seedling responses to high-temperature stress. AoB Plants. https://doi.org/10.1093/aobpla/plv101

Zuriaga E, Blanca JM, Cordero L, Sifres A, Blas-Cerdán WG, Morales R et al (2009) Genetic and bioclimatic variation in Solanum pimpinellifolium. Genet Resour Crop Evol 56:39–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-008-9340-z

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Technological Top Institute Green Genetics (grant number 4CFD047RP, to IR) and the Dutch Topsector Horticulture and Starting Materials (grant number 2013-H320, to IR). We are thankful to Jacob Monash for his kind help in proofreading the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Driedonks, N., Wolters-Arts, M., Huber, H. et al. Exploring the natural variation for reproductive thermotolerance in wild tomato species. Euphytica 214, 67 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-018-2150-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-018-2150-2