Abstract

This paper characterizes the long-run distribution of Austrian public debt using a Markov chain model of the debt-GDP ratio and several key macroeconomic variables. We apply Bayesian techniques to estimate the transition probabilities of the model which allows to incorporate information from other countries. Based on the model, we argue that the historical record of Austrian fiscal policy is consistent with a stable long-run distribution of the debt-GDP ratio with an expected value close to the 60% threshold of the Maastricht treaty. Our results suggests that the strong increase in the debt-GDP ratio in the aftermath of the recent financial crisis should be seen as a transitory tail event rather than as a sign of long-run unsustainability. However, we also show that the existence of a stable long-run distribution depends on a continuing tendency of fiscal policy to “lean against debt” by reducing the primary deficit in face of rising debt. Finally we assess how exogenous shocks to the primary deficit and real GDP growth affect the model-implied distribution.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In recent years the sustainability of public debt has become an issue of great concern in public discourse. The debt crisis in the Eurozone alerted both policy-makers and economists to the fact that government defaults are not exclusively a problem of developing countries. With few exceptions, all major Western economies have seen their public debts rise faster than their national incomes and, if current demographic trends are to persist, a rise in age-related government expenditures will impose more and more pressure on public budgets in the future. Uncertainty about the future growth outlook adds to concerns about the ability of governments to service their debts. In addition, the Eurozone debt crisis has demonstrated that governments of high-debt nations who do not control the currency in which their liabilities are denominated are particularly vulnerable to swings in investor expectations. It is thus crucial to study debt sustainability through the lens of a model that incorporates both the historical record of fiscal policy and exogenous shocks related to the above concerns.

Projections of future public debt face several uncertainties. First, there is policy uncertainty regarding the future development of the tax system and government spending. Second, even if one assumes no changes in tax and spending policies, there is economic uncertainty which must be taken into account. The growth rate of GDP, demographic changes as well as the interest rate at which the government can borrow are part of the economic environment which directly or indirectly affects a country’s public finances. Since this economic environment is subject to random influences, assessing the sustainability of a country’s debt requires an estimation of the (joint) probability distribution of the country’s economic fundamentals and its public debt level.

This paper uses a model developed by Hall (2014) to characterize the long-run distribution of public debt and applies it to the case of Austria. This distribution is derived from a Markov chain model of the debt-GDP ratio and several key macroeconomic variables. The primary advantage of this method is that it generates not only a point prediction of the debt level but gives probabilities of tail events such as an abrupt increase in the debt-GDP ratio above a given threshold. It provides a theory-based empirical test of government debt sustainability insofar as the existence of a stable long-run distribution (a stochastic steady-state) rules out the possibility of an exploding public debt-GDP ratio which would violate the government’s intertemporal budget constraint.

Our paper departs from Hall (2014) by proposing a novel way to estimate the transition probabilities of the underlying Markov chain. When the sample size of observed state transitions is small, “conventional” maximum likelihood methods may run into problems. We take a (partially) Bayesian approach that incorporates prior information about the transition probabilities obtained from observed state transitions in foreign countries which helps to alleviate the small-sample concerns. Having a convincing estimate of the transition probabilities is crucial since they heavily affect the stationary distribution of the Markov chain. Our estimation approach is not fully Bayesian, as we do not estimate all the unknown model parameters jointly from the data, but calibrate some of them relying on previous literature.

The case of Austria is interesting for two reasons. First, Austria is in many respects a typical Eurozone country—both in terms of GDP growth and debt-GDP ratio—and can thus be seen as representative for the Eurozone. Second, Austria has had a fairly long tradition of “activist” fiscal policy which has raised concerns about long-run debt sustainability (Haber and Neck 2008). These concerns have been heightened during the recent financial crisis when the Austrian government stepped in to support the national banking sector leading public debt to exceed 80% of GDP. This raises the question whether the recent spike in Austria’s debt level implies a persistent threat to government solvency or should be seen as a transitory phenomenon instead.

The main focus of this paper is to find and describe the stationary distribution of the debt-GDP ratio under different assumptions about the behavior of fiscal policy and future macroeconomic developments. The stationary debt distribution can be interpreted in two ways: It characterizes the uncertainty about the debt-GDP ratio in the long run conditional on present information about fiscal policy and the state of the economy. Alternatively, it can be viewed as the distribution of the debt-GDP ratio at randomly selected future dates. In addition to calculating the stationary distribution, we use our model to perform medium-run forecasts of the debt-GDP ratio based on various scenarios.

The rest of the paper is in five sections. The next section provides a brief overview of the existing literature on testing debt sustainability. Section 3 describes and discusses the setup of our empirical model. Section 4 explains our estimation approach. In Sect. 5 we apply our model to the case of Austria and present the debt projections for different scenarios derived from our model. The conclusion summarizes the main findings of the paper.

2 Related literature

Assessing long-run fiscal sustainability in the sense of whether or not the government satisfies its intertemporal budget constraint has given rise to a vast literature. Without attempting a comprehensive review, we will briefly describe key contributions in order to put this paper into context. The early literature (e.g. Trehan and Walsh 1991) typically tests if the historical record of fiscal policy supports the hypothesis that the initial debt does not exceed the expected value of future primary surpluses discounted by the interest rate on sovereign debt. This requires that the discounted value of expected future debt converges to zero, which is known as the transversality condition. The validity of testing fiscal sustainability in this way depends crucially on the choice of the discount factor.

In a series of papers, Bohn (1995, 1998, 2008) has pointed out the problems arising from the use of the historical average of government bond yields for discounting future debt. He shows in a stochastic general equilibrium framework that proper discounting should be based on the marginal rate of intertemporal substitution rather than on the historical average. In contrast to the latter, the marginal rate of intertemporal substitution may vary significantly over time and across states of nature. He further demonstrates that using historical averages of risk-free interest rates for discounting can be significantly misleading under rather reasonable conditions. More generally, using the risk-free rate is valid only if at least one of the following holds: (i) no uncertainty, (ii) risk-neutral private agents or (iii) no correlation between future government surpluses and marginal rates of substitution. Mendoza and Ostry (2008) argue in line with Bohn that (i) and (ii) are unrealistic and that (iii) is sharply at odds with empirical findings.

As an alternative to “naive” sustainability tests, Bohn (1998) proposes a simple criterion which is valid under a broad class of models. The “Bohn test” essentially consists of estimating a fiscal reaction parameter \({\upalpha }\) in the equation

where D is the primary budget deficit (non-interest government spending minus government revenue) and B is the government debt level. X is the residual part of the primary balance which may, for instance, reflect business cycle fluctuations or extraordinary defense expenses in times of war. Proposition 1 in Bohn (2008) shows that under fairly general assumptions a positive reaction parameter \({\upalpha }\) is a sufficient condition to guarantee that the government satisfies its intertemporal budget constraint. Importantly, this condition does not rely on specific assumptions about maturity, currency denomination or other characteristics of public debt. Governmental securities can take the form of any contingent or non-contingent financial asset. In addition, the test does not require any explicit knowledge about tax- and expenditure policies since it only tests whether the outcome of those policies is consistent with the intertemoral budget constraint (see Mendoza and Ostry 2008 for a thorough discussion).

The “Bohn test” has been applied to the case of Austria by Getzner et al. (2001), Neck and Getzner (2001) and Haber and Neck (2006). All of these papers find evidence that Austrian fiscal policy has a tendency to “lean against debt” and therefore satisfies Bohn’s criterion for fiscal sustainability. The most recent of these, Haber and Neck (2006), covers the period between 1960 and 2003. They find a structural break in the fiscal reaction parameter in 1974/1975 when the first oil price shock hit the Austrian economy. This result is confirmed by Mauro et al. (2013) who also find structural breaks in the mid-1970s for several European countries. Haber and Neck (2006) find a strong positive and significant reaction of the primary deficit to increases in public debt levels between 1960 and 1974 and a still positive but considerably smaller reaction between 1975 and 2003.

While several contributions use Bohn’s method of estimating fiscal reaction functions to check whether fiscal policy has acted “responsibly” in the past, little effort has been made to study the implied future path of the debt-GDP ratio. In a recent study of US public debt, Hall (2014) proposes a framework that characterizes not only the future expected value of debt but also allows to estimate the probabilities of tail events such as a sequence of below-average economic growth that drives the debt-GDP ratio to abnormally high levels. To our knowledge, ours is the first attempt that applies this framework to the case of Austria. Our method differs from Hall (2014) in that we take a Bayesian approach to estimating the transition probabilities of the Markov-chain model.

3 The model

We consider a stochastic economy in discrete time. At any point in time \(t=1,2,\ldots\), the state of the economy is determined by an integer variable \(s_{t}=1,2,\ldots ,K\) which we refer to as the “fundamental state”. The fundamental state determines key macroeconomic variables like real GDP growth, the unemployment rate, inflation and the real interest rate. The probability of state \(s_{t}\) conditional on observing the states \(s_{t-1}\), \(s_{t-2},\ldots ,s_{1}\) in the past is denoted by \(\mathbb {P}(s_{t}|s_{t-1},s_{t-2},\ldots ,s_{1})\). We assume that the stochastic process underlying our model has the Markov property, i.e.

In addition, we assume that the transition probability between state i and j is independent of time, i.e. for all t,

for all \(i,j=1,2,\ldots ,K\). We will refer to the \(K\times K\) matrix \(\Pi =[{\uppi }_{i,j}]\) as the transition matrix.

Government spending and tax revenues are influenced by the state of the economy through various channels. A high real growth rate increases income tax revenues, high unemployment causes spending on unemployment benefits to rise, high inflation raises revenue from value-added taxes, and so on. Furthermore, governments may also take discretionary actions e.g. to counter recessions. Therefore we model the government’s primary budget balance, defined as non-interest spending minus taxes, as a function of the fundamental state.

The government not only chooses how much to spend and tax, but also which kinds of securities to issue. In principle, it may use a variety of securities with all kinds of state-dependent payoffs and maturities. Here we assume that the government issues only a single type of security, namely a “delta bond” which pays a geometrically decaying coupon. A delta bond issued at time t pays a coupon \({\upkappa }{\updelta }^{j-1}\) at any time \(t+j\) with \(0<{\updelta }<1\) and \(j>0\). We denote the market price of delta bonds issued at time t by \(q_{t}\). Arbitrage in bond markets ensures that the period-t price of a delta bond issued in period \(t-j\) is \({\updelta }^{j}q_{t}\). Hence, every bond issued in \(t-j\) is equivalent to \({\updelta }^{j}\) bonds issued in t, which allows us to convert bonds of all vintages in terms of current-period bonds.

Let \(B_{t}\) denote the amount of bonds outstanding at the end of period t and let \(D_{t}\) be the corresponding primary budget deficit. Then the flow budget identity of the government in period t is

The left-hand side of this equation is the market value of bonds outstanding at the end of period t. The right-hand side represents the financing needs of the government arising from the primary budget deficit and the coupon payments \({\upkappa }B_{t-1}\) as well as the value of bonds carried over from the last period, \({\updelta }q_{t}(s_{t})B_{t-1}\). Note that both the primary deficit and the bond price are functions of the fundamental state.

Under complete asset markets there is a stochastic discount factor \(m(s_{t+n}|s_{t})\) such that \(\mathbb {P}(s_{t+n}|s_{t})m(s_{t+n}=k|s_{t})\) is the market price of a security at time t paying one unit of output if state \(s_{t+n}\) occurs at time \(t+n\) and nothing in any other state or time. The sequence of bond prices \(\{q_{t}\}\) must satisfy the asset pricing equation

for all t. As shown by Bohn (1995), the government’s ability to issue bonds is subject to the transversality condtition

which implies that the value of government debt must be equal to the expected present value of future primary surpluses. Bohn (1998) shows that a sufficient condition for (6) to hold is that the government follows a policy that reacts to rising debt by increasing the primary surplus (or, equivalently, reducing the primary deficit). This is the theoretical basis for the “Bohn test” described earlier. In this spirit, we decompose the primary deficit into an exogenous component \(X_t(s_{t})\) reflecting budgetary shocks which depend on the fundamental state of the economy and an endogenous component measuring the response of the primary deficit to the debt obligations outstanding at the beginning of the period:

The “fiscal reaction parameter” \({\upalpha }\) measures the government’s propensity to reduce the budget deficit in response to an increase in public debt.

For the sake of convenience, let us divide the primary deficit and the outstanding debt through GDP and denote the resulting variables by the corresponding lower case letters \(d_t\), \(x_t\) and \(b_t\). In terms of GDP ratios, Eq. (7) thus becomes

where \(g_{t}(s_{t})\) is the growth factor of real GDP (the real growth rate plus one) in period t. Combining (4) and (8) yields a law of motion for the debt-GDP ratio:

Note that the debt-GDP ratio in period t is a function of the current fundamental state \(s_{t}\) and the debt-GDP ratio in the previous period \(b_{t-1}\) while it is independent of earlier realizations of these variables. Therefore we can treat the pair (\(s_t, b_t\)) as a combined state variable which again follows a Markov process. Our goal is to derive the transition probabilities and, if it exists, the long-run stationary distribution of this Markov chain.

To that end, we first construct the conditional probability density function (pdf) of the combined state \((s_{t},b_{t})\) given \((s_{t-1},b_{t-1})\):

Here the indicator function \({\mathbb {I}}(f)\) equals zero if \(f<0\) and one if \(f\ge 0\) and

The stationary pdf of the combined state \((s_{t},b_{t})\) can then be found, if it exists, by solving the invariance condition

for all (\(s_t,b_t\)). Given \(\mathbb {Q}(s_{t},b_{t})\) one can finally solve for the marginal pdf of \(b_t\):

This allows us to derive the long-run distribution of the debt-GDP ratio implied by our model. The existence of a stationary distribution rules out explosive paths of the debt-GDP ratio and hence is a prerequisite for fiscal sustainability.

How does \({\upalpha }\) influence the existence of a stationary distribution? From the basic theory of stochastic processes, a Markov chain has a unique stationary distribution if and only if it is irreducible and aperiodic.Footnote 1 Roughly speaking, this requires that it is possible, within a finite number of transitions to reach any state \((s_t, b_t)\) irrespective of the current state and that the system can return to every state. From Eq. (8), the higher \({\upalpha }\) is, the lower is the primary deficit \(d_t\) for any given current debt level if \(b_{t-1}>0\). The reverse holds for negative debt levels. Hence, the larger \({\upalpha }\) ceteris paribus, the higher the probability to transition to lower (higher) debt-GDP ratios from any current positive (negative) level. A positive \({\upalpha }\) thus increases the likelihood that a stationary distribution exists.

A positive \({\upalpha }\) is yet neither sufficient nor necessary to rule out explosive debt-GDP ratios. For example, assume \(K=1\) (no fundamental uncertainty) and \(g=1\). Then (9) becomes

which, is a stable first-order difference equation that converges to the steady-state debt-GDP ratio,

if and only if \(({\upkappa }-{\upalpha }+{\updelta }q)/q<1\). As can easily be seen, this stability condition may hold even though \({\upalpha }=0\) and may be violated even though \({\upalpha }>0\).

Applying this model requires three steps. First, we need to define the fundamental states and estimate the state means for the real growth factor, g(s), the bond price q(s) and the external component of the primary deficit x(s). Second, we need to estimate the transition matrix \(\Pi\). Third, given the fundamental states and their transition matrix, we can calculate the transition probabilities of the combined state T and, if it exists, the stationary distribution Q(b). The next section explains our estimation approach in detail.

4 Estimation approach

The first step in applying our model is to estimate the state means from the observed fundamental variables as well as the transition probabilities among states. We observe a vector sequence \(\{y_t\}^T_{t=0}\) of macroeconomic variables which describe the fundamental state of the economy. We include here real GDP growth, inflation, unemployment and the real interest rate. Following Hall (2014) we employ the K-means clustering algorithm to find K clusters in the data which we identify as our fundamental states of nature. Thus we obtain a sequence of integers \(\{s_t\}^T_{t=0}\), where \(s_t\in \{1,2,\ldots ,K\}\) is the observed fundamental state in period t.

Our next goal is to estimate the transition matrix \(\Pi\) from the sequence of observed states.Footnote 2 The conditional probability of \(\{s_t\}^T_{t=0}\) given \(\Pi\) can be expressed as

which is the likelihood of the transition matrix. The likelihood represents the information about the unknown transition probabilities contained in the sequence of observed state transitions. As a result of time-homogeneity, \(\mathbb {P}[s_0,\ldots ,s_{T}|\Pi ]\) is a multinomial probability mass function with \(K\times K\) parameters \({\uppi }_{11},{\uppi }_{12},\ldots ,{\uppi }_{ij},\ldots ,{\uppi }_{KK}\):Footnote 3

Here \(N_{ij}\) is the number of observed transitions from state i into state j:

with \({\mathbb {I}}()\) being the indicator function. Maximizing (14) with respect to \({\uppi }_{ij}\) yields the maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) for the transition probabilities:

for all \(i,j=1,2,\ldots ,K\). This is the estimator used in Hall (2014).

Applying the maximum likelihood estimator can run into problems if the time series of observed states is small. For instance, if \(T=50\) and \(K=5\), then \(N_{ij}=2\) on average, so \({\hat{{\uppi }}}_{ij}\) will assign zero to many transition probabilities. In order to alleviate this problem we follow a Bayesian approach which explicitly takes prior information about the transition probabilities into account. Prior information may come from theoretical considerations or from previous empirical work. In Bayesian estimation, the likelihood is combined with a prior distribution to yield a posterior distribution for the unknown parameters of the model. The posterior summarizes the uncertainty about the transition probabilities given the observed transitions and the prior.

We choose a Dirichlet prior distribution as it is the conjugate prior to the multinomial distribution. This choice allows us to derive closed-form expressions for the posterior mean transition probabilities and spares us from the necessity of numerical posterior simulations. We assume that each row i of \(\Pi\) is independently Dirichlet distributed with hyper-parameters \(\mu _{ij}>0\), \(j=1,\ldots ,K\). Then the prior probability of the transition matrix is:

where \(\mu _{ij}\) indicates the strength of the prior information about the transition probability \({\uppi }_{ij}\). The posterior distribution is obtained via Bayes’ Rule:

The posterior is the conditional probability distribution of the transition matrix given the observed sequence of states \(s_0,\ldots ,s_{T}\). It gives a complete description of the uncertainty about transition probabilities taking into account the information contained in the observed state transitions as well as the information contained in the prior.Footnote 4

Note that the posterior is also a Dirichlet distribution with parameters \(N_{ij}+\mu _{ij}\). Therefore, it is straightforward to compute the posterior mean of \({\uppi }_{ij}\):

Clearly, the posterior mean estimate is a weighted sum of the prior mean \({\bar{{\uppi }}}_{ij}\) and the MLE, where the weight reflects the relative strength of the prior:

with \({\bar{{\uppi }}}_{ij}\equiv \frac{\mu _{ij}}{\sum ^K_{j=1}\mu _{ij}}\). In the limit, as \(\sum ^K_{j=1}N_{ij}\) becomes infinitely large, the posterior mean is equal to the ML estimator. Informally speaking, as the sample size gets larger, the posterior mean approaches the “conventional” estimator everything else remaining equal.

The critical step in Bayesian estimation is the elicitation of a prior distribution. We propose a procedure that uses data from foreign countries with similar economic characteristics to construct a prior. In particular, we construct the prior mean by taking a weighted average of the estimated transition matrices of foreign countries, where each country’s weight is based on a similarity measure between its fundamental states and those of the main country of interest. The rationale for this procedure is as follows. We can think of each country’s history of observed fundamental states as one particular draw from a Markov chain whose transition probabilities are unknown and need to be estimated. Suppose we have a set of countries whose fundamental states are drawn from the exact same Markov chain. Then all these histories provide (equally) useful information for estimating the transition probabilities. The closer the similarity between two countries, the more useful each country’s history is for the estimation.

Suppose, then, we have data from H foreign countries and found K fundamental states (clusters) for each of them. Let the matrix of state means of the observed macroeconomic variables (real GDP growth, inflation, unemployment, and real interest rate) of country \(h, h=1,\ldots ,H\) be denoted by \(\bar{y}_h\). Furthermore, let \(\bar{y}\) be the matrix of state means of the reference country. Then the weight of country h is given by

where ||.|| is the Frobenius matrix norm, which is the matrix analog of the Euclidean distance between vectors. The larger the distance between the state means of country h and those of the reference country, the smaller is the weight \({\upomega }_{h}\). Note also that \(\sum ^{H}_{h=1}{\upomega }_{h}=1\), which justifies the term weight.

From the observed sequence of states \(\{s^h_{t}\}\) for country h, we obtain the MLE of this country’s transition probabilities using the formula (16):

where \(N^{h}_{ij}\) is the number of transitions from state i into state j observed in country h. The hyper-parameter \(\mu _{ij}\) is then calculated as the weighted sum of observed transitions from i into j over all countries:

By construction, \(\mu _{ij}\), which measures the strength of the prior, increases in the (weighted) number of observed transitions from i to j. With some algebra, one can show that the prior mean of the transition probability from i to j is

with \(\Omega _{h}\equiv \frac{{\upomega }_{h}\sum ^{K}_{j=i}N^{h}_{ij}}{\sum ^{H}_{h=1}{\upomega }_{h}\sum ^{K}_{j=i}N^{h}_{ij}}\). Hence the prior mean of the transition probabilities is a weighted average of the ML estimates of foreign countries.

To illustrate how our procedure works, imagine that we have H countries whose fundamental states are all exactly the same as those of the reference country and we observe a sequence of states of length T for each country. In this case, each observed transition would receive exactly the same weight in calculating the posterior mean irrespective of where the transition occurred just as if we would observe a sequence of states of length \(H\times T\) in the reference country. This helps to overcome the small sample problem that could arise if we just included the T observed states from the reference country.

Having obtained an estimate of the transition matrix of fundamental states in the first step, we can now calculate the transition probabilities for the combined states. Here we again follow Hall (2014) and discretize the debt-GDP ratio into M regions which gives a combined state space of \(K\times M\) elements. Plugging the estimated transition probabilities \(\tilde{{\uppi }}_{i,j}\) Footnote 5 from (19) into (10) gives an estimated transition matrix for the combined state \(\tilde{T}\) with dimension \((K\times M)\times (K\times M)\). In calculating \(\tilde{T}\), estimates for the fiscal reaction parameter \({\upalpha }\) as well as for the delta-bond parameters \({\upkappa }\) and \({\updelta }\) are needed. In contrast to Hall (2014) who uses a calibration procedure, we rely on estimates of \({\upalpha }\) from standard Bohn-test regressions. Our choices of \({\upkappa }\) and \({\updelta }\) are explained in the next section.

It should be noted that our estimation procedure is only partly Bayesian in so far as we do not attempt to estimate the parameters \({\upalpha }\), \({\upkappa }\) and \({\updelta }\) jointly with the transition probabilities. Instead, we calibrate these parameters relying on previous literature and show how varying the critical “Bohn” parameter \({\upalpha }\) changes the resulting stationary distribution. A fully Bayesian approach would treat these parameters in the same way as we treat the state transition probabilities and try to characterize the full posterior distribution of all the unknown parameters of the model. However, this would significantly increase the computational cost of the estimation without obvious benefits for our analysis of the long-run debt distribution.

The final step is to calculate the (approximated) stationary distribution of the combined state from \(\tilde{T}\). To do that, we insert \(\tilde{T}\) into (11) yielding

for all \(m^\prime =1,2,\ldots K\times M\). Solving for \(\tilde{\mathbb {Q}}\) is feasible using standard techniques. From the stationary joint distribution, it is easy to back out the marginal distribution of the debt-GDP ratio via (12).

It is important to note that \(\tilde{T}\), \(\tilde{\mathbb {Q}}\), and \(\tilde{Q}\) are completely determined by the estimated fundamental states and their associated transition matrix for given choices of \({\upalpha }\), \({\upkappa }\) and \({\updelta }\). This explains why having plausible estimates of the fundamental transition matrix is crucial.

5 Application: fiscal sustainability in Austria

In this section we apply our model to the case of Austria to investigate the sustainability of its public debt by calculating the long-run debt distribution. We also use the model to produce medium-run projections of the debt-GDP ratio under five different scenarios.

Our data come from two different, publicly accessible sources listed in Table 7 in “Appendix”. We obtain yearly observations on real GDP growth, consumer price inflation, unemployment and the real interest rate together with data on the primary budget balance and gross government debt for the period 1975 to 2015. We set K=5, i.e. we let the K-means clustering algorithm identify five fundamental states of the Austrian economy. Table 1 shows the mean values of the considered variables for each state, Table 8 in “Appendix” lists the fundamental state that the algorithm assigns to each year in the sample.

Under our choice of K=5, the clustering method assigns a separate fundamental state to the year 2009 when the repercussions of the global financial crisis severely hit the Austrian economy. State 2 incorporates most of the other “crisis years” including those in the aftermath of the second oil price shock (1980, 1981, 1984) as well as those after the bursting of the New-Economy bubble (2001-2003). The average real growth rate in this fundamental state is however still positive reflecting the relatively stable evolution of the Austrian economy which hardly went through prolonged slumps over the sample period. State 3 covers with two exceptions the most recent low growth-low real interest period after 2007. The remaining states 4 and 5 are both characterized by robust growth rates. We label state 4 as the “normal state” given that it occurs most frequently in our sample period. State 5 can be thought of as a high growth state that covers years of economic boom (e.g. 1999, 2006) as well as recovery years (e.g. 1976, 2004). Note that in contrast to Hall (2014), unemployment plays only a minor role in the identification process which can be traced back to the strong tendency of Austria’s fiscal policy to “lean against unemployment” (see Haber and Neck 2006 for a discussion).Footnote 6

Austrian public finances, 1975–2015. a Gross Government Debt, percent of GDP and b Primary Budget Balance, percent of GDP. Note Data sources: see Table 7 in “Appendix”

A first look at the evolution of the Austrian debt-GDP ratio over the sample period (see Fig. 1) shows why one might be concerned about fiscal sustainability. Government debt rose steadily from around 22% of GDP in 1975 to above 85% in 2015. In contrast, the primary budget balance in percent of GDP shows no obvious trend over that period. A regression of the primary balance on debt (both measured in percent of GDP) yields a coefficient of 0.045 (t-ratio 2.19) after controlling for real GDP growth and unemployment.Footnote 7 This means that the primary surplus reacted positively to increasing government debt over the period under consideration, so Austrian fiscal policy seems to pass the “Bohn test” of sustainability. This result is broadly in line with the results of Haber and Neck (2006) who also found a positive fiscal reaction parameter. Our point estimate is considerably lower than theirs probably due to the fact that it is based on a different sample period. The goal of our analysis is to go beyond this regression-based test and to see whether a long-run distribution of the debt-GDP ratio exists, how it looks like if it exists and how it is affected by changes in parameters.

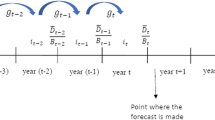

As discussed above, the main input into our empirical model are the exogenous component of the primary deficit x, the bond price q, the growth factor g, the parameters \({\upalpha }\), \({\updelta }\) and \({\upkappa }\) as well as the transition probabilities between the fundamental states.

For estimating the transition matrix \(\Pi\) we combine the information contained in the state transitions observed in Austria with those observed in a set of foreign countries. The latter set consists of four European countries with strong economic ties to Austria, namely France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland. We expect these countries to share many economic characteristics with Austria both in terms of economic structure and the business cycle. For each of these countries we obtain the same macroeconomic data (from the same sources) as for Austria and find their respective fundamental states by K-means clustering. From the state means we calculate country weights shown in Table 2 using the formula (21) above. As one might expect, Germany gets the biggest weight indicating that the German fundamental states are “most similar” to the Austrian ones; the combined weight of Germany and Switzerland is about 2/3; Italy has the lowest weight.

With these country weights at hand, we construct the prior mean of the transition matrix as in (24) which we show in Table 3. It is the weighted average of the ML estimated transition matrices for France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland. The prior means are those transition probabilities which we expect to observe before seeing the sequence of Austrian state transitions. Using the formula (19) derived above, we combine the prior means with the ML estimates for Austria (see Table 4) to obtain the posterior mean estimates of the transition probabilities (see Table 5).

Comparing the posterior mean to the MLE, one clearly sees what our Bayesian approach achieves. ML estimation results in almost half of the estimated transition probabilities being zero—a consequence of our relatively short time series. Relying on these estimates could seriously affect the calculation of the long-run debt distribution. Including the information from foreign countries contained in the prior changes most of these zero-entries to positive ones yielding a more convincing estimate of the transition matrix.

To further check the credibility of our transition matrix and thus of our subsequent inferences, Fig. 8 shows the state probabilities implied by the posterior transition matrix over a period of 40 years. We start from the “normal state” 4. As can be seen from the figure, state probabilities converge relatively quickly to their stationary values. An economy governed by this transition matrix would be expected to spend a tiny fraction of years in state 1 (“financial distress”) and roughly one-third of the years in the “normal state”. Also “low growth-low real interest” years (state 3) would be expected to occur relatively often which is mostly the consequence of the high probability to remain in state 3 once having reached it. Finally, roughly every fifth year would be characterized by abnormally low growth and also every fifth by abnormally high growth (state 5).

Having calculated the fundamental states and the transition matrix, we now need to determine the exogenous component of the primary deficit as well as the bond price for every fundamental state. We calculate the former directly from the data using the definition in (7) for three different values of the fiscal reaction parameter, namely our own estimate \({\upalpha }=0.045\), the Haber-Neck estimate \({\upalpha }=0.09\) Footnote 8 and \({\upalpha }=0\). The bond price is calculated in a way similar to Hall and Reis (2015). We first note that the real interest rate must satisfy the asset pricing relation

for all \(i=1,2,\ldots ,5\), where we use the posterior mean estimates of the transition probabilities \(\tilde{{\uppi }}_{i,j}\). We assume, consistent with a broad class of asset pricing theories, that the stochastic discount factors \(m_{i,j}\) take the form \({\upbeta }{\upgamma }_j/{\upgamma }_i\), where \({\upbeta }\) is the time discount factor and \({\upgamma }\) is marginal utility. We normalize marginal utility in state 4 to unity, i.e. \({\upgamma }_4 =1\). Hence (26) gives a system of 5 equations in 5 unknowns which can be solved by standard techniques. Having backed out the stochastic discount factors \(m_{i,j}\) in this way, we can solve the system of bond pricing equations

for all \(i=1,2,\ldots ,5\) for given parameters \({\upkappa }\) and \({\updelta }\). We set \({\updelta }= 0.8\dot{3}\) implying an average debt maturity of 6 years consistent with the finding of Mosley (2003) and choose \({\upkappa }\) in such a way that \(q_4=1\), which leads to \({\upkappa }=0.2\).Footnote 9 Table 6 lists the mean values of x for each state depending on different values of \({\upalpha }\) as well as q. Note that a higher \({\upalpha }\) means that a larger portion of the observed primary deficit is attributed to the exogenous component.

Stationary distribution of debt-GDP ratio, different scenarios. Note Approximated marginal distribution of the debt-GDP ratio derived from \(\tilde{Q}\), see Eq. (11). For description of scenarios see main text

We are now ready to solve for the stationary distribution of the debt-GDP ratio. We do so for five scenarios. Our baseline case (scenario 1) assumes that the fundamental states of the Austrian economy as well as the fiscal reaction parameter remain unchanged in the future. Scenarios 2 and 3 assume the same fundamental states but different fiscal reaction parameters. Scenarios 4 and 5 assume different exogenous changes to the primary deficit and the real growth rate while taking the baseline fiscal reaction parameter. For each of these scenarios we obtain projections of the debt ratio from 2016 through 2040 by iterating the Markov chain forward from the last observed state.

For all scenarios except scenario 3, a stationary distribution can be found. Figure 2 shows the approximated long-run marginal distribution of the debt-GDP ratio \(\tilde{Q}\) for all scenarios for which it exists. As explained above, the existence of a stationary distribution rules out explosive paths of the debt-GDP ratio and hence indicates fiscal sustainability in the sense of satisfying the transversality condition (6). The stationary distribution can be interpreted in two different ways. In a Bayesian sense, it characterizes the long-run uncertainty about the debt-GDP ratio given our present knowledge of the fundamental states, their transition probabilities and the fiscal reaction parameter. In a frequentist sense, it shows the distribution of the debt-GDP ratio at randomly selected future dates. We will now describe each scenario in detail (Fig. 3).

Baseline scenario, debt projection, 2016–2040. Note Projection of debt-GDP ratio derived from the approximated transition matrix \(\tilde{T}\), see Eq. (10). Assumes \({\upalpha }=0.045\) estimated from “Bohn regression”, see Table 9 in “Appendix”. Black line mean value of the debt-GDP ratio; dark grey area 50% probability interval; light grey area 90% probability interval

Under our baseline scenario, with \({\upalpha }=0.045\) estimated from a “Bohn regression”, a long-run distribution of the debt-GDP ratio exists with a mean of 58% (see blue line in Fig. 2). This is a clear indication that Austrian fiscal policy is sustainable if the conditions of the past, including the past tendency of the government to lean against increasing debt by reducing the primary deficit, continue to hold in the future. However, the long-run probability of debt to exceed the Maastricht limit of 60% of GDP is about 47%, which is quite substantial. With 90% probability, the debt-GDP ratio will be in the range of 32–84% in the long run. As seen in Fig. 7, the baseline scenario predicts that the mean debt-GDP ratio slowly declines from its current value to about 70% in 2040. It doesn’t rule out, however, that the debt will continue to rise during the next decade.

It is instructive to ask what our model would have predicted before the “Great Recession” hit. We therefore conduct a counterfactual debt projection under our baseline scenario by iterating the Markov chain forward from starting values of 2007, the year before the global financial crisis. At that time Austria’s public debt stood at 65% of GDP and the economy was in fundamental state number 5. From this original state, our model would have predicted a slow decline in the debt-GDP ratio (in expectation).Footnote 10 The probability that the debt-GDP ratio would be above 80% by 2010 was below 5%. So, according to our model, the observed steep rise in the debt ratio constitutes a tail event from a pre-crisis point of view (Fig. 4).

Scenarios 2 and 3, debt projections, 2016–2040. a Scenario 2: \({\upalpha }=0.09\) and b scenario 3: \({\upalpha }=0\). Note Projection of debt-GDP ratio derived from the approximated transition matrix \(\tilde{T}\), see Eq. (10). Scenario 2 assumes \({\upalpha }=0.09\) as in Haber and Neck (2006); scenario 3 assumes \({\upalpha }=0\). Black line mean value of the debt-GDP ratio; dark grey area 50% probability interval; light grey area 90% probability interval

Scenario 2 demonstrates how a larger fiscal reaction parameter affects the long-run debt distribution. The main effect of a higher \({\upalpha }\) is that the long-run debt distribution is more narrowly concentrated around the mean (see green line in Fig. 2). The long-run mean is slightly higher compared to the baseline, namely 59%, and the 90% probability interval narrows to the range of 40–77%. To understand the effect on the long-run mean, recall that setting a higher \({\upalpha }\) implies larger primary deficits in all fundamental states (see Table 6), which tends to increase the debt-GDP ratio ceteris paribus. This effect is counteracted by more “leaning against debt”. In this scenario, the debt is predicted to be paid off more quickly compared to the baseline and approaches 63% of GDP by 2040 (see Fig. 5a). Hence, if the Haber-Neck estimate of \({\upalpha }=0.09\) were “true”, debt sustainability would clearly not be an issue. On the other hand, if this were indeed the true \({\upalpha }\), the occurrence of the current debt-GDP ratio of more than 80% would be very unlikely with a long-run probability of 1.6%. The fact that such high debt-GDP ratios have been observed may suggest that the true fiscal reaction parameter is significantly lower than 0.09.

Scenario 3 shows what would happen if Austrian fiscal policy had no tendency to “lean against debt”, i.e. \({\upalpha }=0\). In this case, we do not find a stationary distribution. Under this scenario, the mean debt-GDP ratio is seen in Fig. 5b to continue to rise from its current value over the entire projection horizon. Moreover, the distribution is seen to widen quickly, which implies that explosive debt paths cannot be dismissed. The probability that debt will exceed 100% of GDP by 2040 is close to 50%. This demonstrates that a positive fiscal reaction is crucial to rule out forever growing debt in Austria. Intuitively, this is clear from looking at the long-run means of real GDP growth, the real interest rate and the exogenous part of the primary deficit, which are 1.97, 2.88 and -0.23%, respectively.Footnote 11 The interest-growth differential is thus clearly positive and the primary balance is only slightly positive on average, so that debt would grow without limit from any level above 25% of GDP as long as fiscal policy exerts no counteracting effort.

Scenarios 4 and 5, debt projections, 2016–2040. a Scenario 4: \({\upalpha }=0.045\), 1% shock to x and b scenario 5: \({\upalpha }=0.045\), 1% increase in x, 0.5% decline in g Note Projection of debt-GDP ratio derived from the approximated transition matrix \(\tilde{T}\), see Eq. (10). Black line mean value of the debt-GDP ratio; dark grey area 50% probability interval; light grey area 90% probability interval

In scenario 4, we assume a permanent increase in the exogenous part of the primary deficit by 1% of GDP throughout all fundamental states while everything else is the same as in scenario 1. One reason for such a deficit shock could be an increase in age-related government expenditures due to demographic changes. The European Commission (2012) estimates that these expenditures could increase to 4.4% of GDP by 2060. Another reason might be a permanently higher unemployment rate which may also lead to higher public expenditures. Under these circumstances, the long-run debt distribution is shifted to the right relative to the baseline scenario, with a mean of 89%. The forecast associated with this scenario (Fig. 6a) shows that debt can be expected to stay at current levels, but the risks of an increase to 100% of GDP or higher are not negligible.

Finally, scenario 5 is the same as scenario 4, except that we add a permanent reduction in the real growth rate of 1/2 percentage point for all states. The source of this growth reduction could again be an ageing population or a reduced innovative capacity of the economy and is motivated by the hypothesis of “secular stagnation” which has (re-)emerged recently in the growth literature. As one might expect, this scenario implies a further shift in the long-run distribution towards higher debt-GDP ratios. The mean is about 104% of GDP, and the risk of debt exceeding 100% in the long run is about 58%, similar to scenario 3. It should be stressed that, both in scenario 4 and 5, debt is still sustainable in terms of our model, although it might not be so from a political perspective. Under either scenario, it is very unlikely that Austria’s public debt will return to the Maastricht limit of 60% any time in the next two decades.

One limitation of our model is that it assumes away any feedback between the debt level and the fundamental state of the economy. Yet theoretical models of sovereign default suggest,Footnote 12 and recent experience in the Eurozone seems to confirm, that markets may demand a default risk premium on government bonds once the debt exceeds a certain level. It is thus instructive to see how the long-run debt distribution changes if we allow for such a feedback effect. In particular, we allow for the possibility that bond prices fall by 12% when debt exceeds 100% of GDP. We think of this scenario as a “debt crisis” similar to those that occurred in Greece and Ireland. Figure 6 shows the resulting long-run debt distribution when the possibility of a debt crisis is included. The main effect is that the debt distribution becomes bimodal. The lower mode is at about 55% of GDP, roughly the same as the mode of the baseline distribution, while the higher mode is at 152% of GDP. Hence, under this scenario, there is a considerable risk that debt rises to very high levels. It should be mentioned, however, that the stationary distribution is quite sensitive to the assumptions about the decline in the bond price and the critical debt level. For instance, if we assume a decrease in bond prices by 15% or more, we do not find a stationary distribution at all.

Stationary distribution of debt-GDP ratio, “debt crisis” scenario. Note Approximated marginal distribution of debt-GDP ratio derived from \(\tilde{Q}\), see Eq. (11). For description of scenarios, see main text

6 Conclusion

In conclusion, our empirical model of Austrian fiscal policy implies a stable long-run distribution of the debt-GDP ratio whose mean is below the Maastricht threshold of 60%. Under our baseline scenario, fears of an endless upward spiral of debt cannot be supported. Under this scenario, the recent spike in the debt-GDP ratio that occurred in the aftermath of the “Great Recession” should be seen as a tail event that is transitory rather than permanent and unlikely to be repeated in future. However, the existence of the stationary debt distribution critically hinges on a positive fiscal reaction parameter, i.e. the tendency of primary deficits to decline when debt increases. Should Austria’s fiscal policy stop “leaning against debt” in future, explosive debt paths cannot be ruled out. In such a no-fiscal-reaction scenario, there is a significant chance that Austrian public debt exceeds 100% of GDP by 2040. Our projections also show that even a small permanent deterioration in the exogenous part of the primary deficit, for instance due to increased age-related expenditures, renders such debt levels quite likely. The likelihood of debt-GDP ratios exceeding 100% is further increased when one assumes a secular decline in economic growth. This indicates that the costs associated with an ageing population as well as low long-run growth prospects are serious obstacles for bringing down the debt. Lastly, we also investigate the consequence on the long-run debt distribution of a discrete decline in government bond prices at a certain critical debt threshold. We find that such a “debt crisis” scenario can generate a non-negligible probability that Austria’s public debt reaches debt levels of 150% of GDP or higher.

These conclusions come with some caveats. First, our criterion of debt sustainability is relatively weak insofar as it merely requires fiscal policy to respect a transversality condition. Even debt levels that are high from a historical point of view could still be sustainable in this sense. However, the Eurozone debt crisis has highlighted the fact that financial markets’ willingness to lend to the government can change quickly even at relatively low levels of debt. Second, our model assumes that the government always services its debt. This may be a reasonable assumption in the case of Austria, which indeed never defaulted since World War II, but is not adequate in general. Extending the present model to explicitly allow for government default could be a worthwhile enterprise for future research. Such an extension would then permit us to estimate the likelihood of default at any point in the future. Finally, it is important to understand the conditional nature of our projections. The debt projections in this paper are derived from economic developments and policy behavior observed in the past. Both may subject to drastic change which is impossible to forecast. The projections are nevertheless useful in characterizing the range of likely outcomes one may expect for reasonable variations in the conduct of fiscal policy.

Notes

See e.g. Ljungqvist and Sargent (2012) chapter 2.2.

In our model, transition probabilities are assumed to remain constant through time, which is controversial in the literature. One way to estimate models with time-varying transition probabilities is Kaufmann (2015). However, this procedure would be much more complex computationally than our proposed estimation approach, while the substantive results of this paper would likely remain unchanged.

We will ignore irrelevant normalizing constants throughout.

For a discussion of the Dirichlet-multinomial model see Avetisyan and Fox (2012).

We henceforth use a tilde to denote estimated parameters.

The choice of K = 5 is, of course, somewhat arbitrary. We have experimented with various reasonable values for K and chose the one allowing for the most intuitively plausible description of Austria’s economic history over the sample period. Note that this implicit identification strategy also addresses the “labelling switching” problem often associated with Bayesian mixture models (see Jasra et al. 2005. We found the results of the paper robust to (reasonable) variations in K. The files for our calculations are available upon request.

See full regression results in “Appendix”.

Haber and Neck (2006) offer different estimates based on different specifications of the “Bohn regression”. We take their baseline estimate for the post-1975 period reported in table 1 on page 143.

Mosley (2003) reports average debt maturity on outstanding government bonds for the year 1996 while average maturities have modestly increased since then. In the context of our model, the choices of \({\updelta }\) and also of \({\upkappa }\) have negligible effect on the calculations.

See Fig. 8 in “Appendix”.

The long-run means are calculated from the stationary distribution of the estimated transition matrix \(\tilde{\Pi }\) and the state means of g, r, and x.

See e.g. Arellano (2008).

References

Arellano C (2008) Default risk and income fluctuations in emerging economies. Am Econ Rev 98(3):690–712

Avetisyan M, Fox J-P (2012) The dirichlet-multinomial model for multivariate randomized response data and small samples. Psicol Int J Methodol Exp Psychol 33(2):362–390

Bohn H (1995) The sustainability of budget deficits in a stochastic economy. J Money Credit Bank 27(1):257–271

Bohn H (1998) The behavior of us public debt and deficits. Q J Econ 113(3):949–963

Bohn H (2008) The sustainability of fiscal policy in the United States. In: Neck R, Sturm JE (eds) Sustainability of Public Debt. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp 15–49

European-Commission (2012) Fiscal sustainability report. Technical report, European Economy No. 8

Getzner M, Glatzer E, Neck R (2001) On the sustainability of austrian budgetary policies. Empirica 28(1):21–40

Haber G, Neck R (2006) Sustainability of austrian public debt: a political economy perspective. Empirica 33(2–3):141–154

Haber G, Neck R (2008) The long shadow of Austrokeynesianism? In: Neck R, Sturm JE (eds) Sustainability of public debt. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp 107–130

Hall RE (2014) Fiscal stability of high-debt nations under volatile economic conditions. Ger Econ Rev 15(1):4–22

Hall RE, Reis R (2015) Maintaining central-bank financial stability under new-style central banking. NBER Working Papers 21173, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc

Jasra A, Holmes CC, Stephens DA (2005) Markov chain Monte Carlo methods and the label switching problem in Bayesian mixture modeling. Statistical Science 20(1):50–67

Kaufmann S (2015) K-state switching models with time-varying transition distributions—Does loan growth signal stronger effects of variables on inflation? J Econom 187(1):82–94

Ljungqvist L, Sargent TJ (2012) Recursive macroeconomic theory. MIT Press, Cambridge

Mauro P, Romeu R, Binder AJ, Zaman A (2013) A modern history of fiscal prudence and profligacy. IMF Working Papers 13/5, International Monetary Fund

Mendoza EG, Ostry JD (2008) International evidence on fiscal solvency: Is fiscal policy responsible? J Monet Econ 55(6):1081–1093

Mosley L (2003) Global capital and national governments. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Neck R, Getzner M (2001) Politico-economic determinants of public debt growth: a case study for austria. Public Choice 109(3–4):243–268

Trehan B, Walsh CE (1991) Testing intertemporal budget constraints: theory and applications to us federal budget and current account deficits. J Money Credit Bank 23(2):206–223

Acknowledgments

Open access funding provided by University of Graz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper was supported by funds of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank (Austrian Central Bank, Anniversary Fund, project number: 15786). Maximilian Goedl is grateful to the Austrian Marshall Plan Foundation for research funding. We would like to thank Robert E. Hall for providing his MATLAB code which were a great help in our computations. We also thank Joern Kleinert, Sofie Waltl, the participants in the Workshop “Geschichte der österreichischen Staatsverschuldung: Ursachen-Vergleiche-Auswirkungen” at the University of Graz and the participants of the Annual Meeting of the Austrian Economic Society 2015 in Klagenfurt for valuable comments.

Appendix

Appendix

This appendix contains detailed description of data sources used in the empirical application as well as tables and figures not included in the main body of the text (Tables 7, 8 and 9; Figs. 7 and 8).

Counterfactual debt projection, 2008–2033. Note Projection of debt-GDP ratio derived from approximated transition matrix \(\tilde{T}\), see Eq. (10). Assumes \({\upalpha }=0.045\) estimated from “Bohn regression”, see Table 9 in “appendix”. Counterfactual from observed state in 2007. Black line mean value of the debt-GDP ratio; dark grey area 50% probability interval; light grey area 90% probability interval

State probabilities over 40 periods starting in state 4. Note State probabilities calculated from the matrix of posterior transition probabilities between fundamental states (Table 5) for a period of 40 years. The simulation starts in our “normal state” (state 4)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Goedl, M., Zwick, C. Assessing the stochastic stability of public debt: the case of Austria. Empirica 45, 559–585 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-017-9376-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-017-9376-4