Abstract

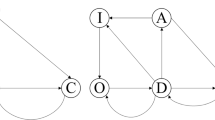

Using a simple decision-theoretic approach, we formalize how agents with different kinds of intrinsic motivations react to the introduction of monetary incentives. We contend that empirical results supporting the existence of a crowding-out effect under various legal procedures hide a more complex reality, where some individuals contribute thanks to these additional monetary incentives while others reduce their contributions. Our approach allows us to study the theoretical ability of the self selection mechanism (Mellström and Johannesson in J Eur Econ Assoc 6:845–863, 2008; Beretti et al. in Kyklos 66(1):63–77, 2013) to reduce the likelihood to backfire against the cause it is meant to promote. This mechanism consists of a monetary payment for the pro-social behavior and it offers agents the choice to either keep the money for themselves or to direct it to a charity. We show that this legal procedure dominates others more classical procedures because it taps wisely into the motivational heterogeneity of individuals. It uses a self-selection mechanism to match adequate monetary incentives with individuals’ types regarding intrinsic motivations. It may even turn a situation subject to crowding-out into a crowding-in outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It was an idea present in the air even before it has been studied in scientific articles. One of the authors of this article has once been offered a similar mechanism by a scientific journal, early in the 2000s. If his evaluation report was delivered in due time, he would be offered the choice of a payment either for himself or for an NGO caring for children in India.

For instance, let us consider that intrinsically motivated donators are those who enjoy donating for its own sake. If we study experimental results of dictator games, we get a whole range of individuals from those giving nothing to those giving their own endowments.

Agents have, possibly, very different exogenous incomes. Due to linearity assumptions in our model, this source of heterogeneity plays no role on agents’ incentives. In a more complex model one can expect that wealthier (resp., poorer) people can be more interested by signaling their qualities (resp., gaining some money) than by the relative insignificant money incentive. The income dimension is also present in some legal incentives. For instance, in Finland speeding fines are linked to income, with penalties calculated on daily earnings. In 2015, a Finnish speeding millionaire was fined about 54.000 euros for being caught doing 103km/h in an area where the speed limit is 80km/h (https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-news-from-elsewhere-31709454).

Experienced utility functions would rather incorporate altruism, and capture the public good collectively created by inserting the others’ aggregated contribution as an argument in utility functions of the kind \(U^{i}(x_{i},x_{-i},f).\)

The parameter \(a_{i}\) could also represent the degree of altruism or reciprocity.

In the case of organ donation, it has been argued that paying or more precisely compensating some expenses related to organ donation can support the donator’s decision, but increasing the payment size by considering organs as a commodity activates a repugnance effect (Capron and Danovitch 2014; see also Roth 2007). In another context, the Resource Guide to U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act published in November 2012 (http://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/criminal-fraud/legacy/2015/01/16/guide.pdf) by the United States Department of Justice and the Securities and Exchange Commission stipulates regarding payments that “size can be telling, as a large payment is more suggestive of corrupt intent to influence a non-routine governmental action” (emphasis added).

Moreover, in addition to obvious intuitive reasons based on empirical evidence, we argue that people enjoy the possibility of choosing by themselves, even at a cost (Frey and Stutzer 2005).

For instance, Tan and Low (2011) showed that subtle changes that do not make sense from an economic perspective change people’s perceptions and behaviours. They explain that the words used to describe incentives for organs donors can dramatically change people’s perceptions and subsequent behaviours. They cite the fact that the Singapore government paid a great deal of attention to the words used to describe these incentives (by avoiding the word ‘payment’ and preferring ‘reimbursement’ to ‘defray the costs or expenses’ associating with organ donation) in order to avoid crowding out prosocial motivations.

We assume that offering choice does not affect parameters in utility functions. Nevertheless, a natural extension to our contribution will be to consider how the value of t and the shape of the moral repugnance function would be affected if individuals themselves can choose between the two options. Relaxing these these assumtions will considerably complicate the analysis and is beyond the scope of your analysis.

Even if it is realistic, our assumption overlooks a possible information effect which appears when the payment offered acts as a signal that the cause is serious and worth-supporting.

References

Atiq, E. H. (2014). Why motives matter: Reframing the crowding out effect of legal incentives. Yale Law Journal, 123(4), 1070–1117.

Ayres, I., & Braithwaite, J. (1992). Responsive regulation: Transcending the deregulation debate. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bar-Gill, O., & Fershtman, C. (2005). Public policy with endogenous preferences. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 7(5), 841–857.

Bénabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2003). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Review of Economic Studies, 70, 489–520.

Bénabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2006). Incentives and prosocial behavior. American Economic Review, 96, 1652–1678.

Beretti, A., Figuières, C., & Grolleau, G. (2013). Using money to motivate both saints and sinners: A field experiment on motivational crowding-out. Kyklos, 66(1), 63–77.

Bernheim, D., & Rangel, A. (2007). Toward choice-theoretic foundations for behavioral welfare economics. American Economic Review, 97(2), 464–470.

Bernheim, D., & Rangel, A. (2009). Beyond revealed preference: Choice theoretic foundations for behavioral welfare economics. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(1), 51–104.

Bolle, F., & Otto, P. E. (2010). A price is a signal: On intrinsic motivation, crowding-out, and crowding-in. Kyklos, 63, 9–22.

Bowles, S. (2008). Policies designed for self-interested citizens may undermine “The Moral Sentiments”: Evidence from economic experiments. Science, 320, 1605.

Bruno, B. (2013). Reconciling economics and psychology on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 6(2), 136–149.

Capron, A. M., & Danovitch, G. (2014). We shouldn’t treat kidneys as commodities, Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 21, 2019, from http://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-0630-danovitch-and-20140630-story.html.

Cooter, R. (2000). Do good laws make good citizens: An economic analysis of internalized norms. Virginia Law Review, 86, 1577–1601. https://doi.org/10.2307/1073825.

Dwenger, Nadja, Kleven, Henrik, Rasul, Imran, & Rincke, Johannes. (2016). Extrinsic and intrinsic motivations for tax compliance: Evidence from a field experiment in Germany. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 8(3), 203–232.

Ellingsen, T., & Johannesson, M. (2008). Pride and prejudice: The human side of incentive theory. The American Economic Review, 98(3), 990–1008.

Feld, L., Frey, B., & Torgler, B. (2006) Rewarding honest taxpayers? Evidence on the impact of rewards from field experiments. CREMA, Working Paper no. 2006-16.

Feldman, Y., & Lobel, O. (2010). The incentives matrix: The comparative effectiveness of rewards, liabilities, duties, and protections for reporting illegality (June 7, 2009). Texas Law Review, 87, San Diego Legal Studies Paper No. 09-013. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1415663.

Feldman, Y., & Perez, O. (2012). Motivating environmental action in a pluralistic regulatory environment: An experimental study of framing, crowding out, and institutional effects in the context of recycling policies. Law and Society, 46(2), 405–442.

Fleurbaey, M., & Schokkaert, E. (2013). Behavioral welfare economics and redistribution. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 5(3), 180–205.

Frey, B. S., & Oberholzer-Gee, F. (1997). The cost of price incentives: An empirical analysis of motivation crowding-out. The American Economic Review, 87, 746–755.

Frey, B. S., Benz, M., & Stutzer, A. (2004). Introducing procedural utility: Not only what, but also how matters. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 160, 377–401.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2005). Beyond outcomes: Measuring procedural utility. Oxford Economic Papers, 57, 90–111.

Gneezy, U., Meier, S., & Rey-Biel, P. (2011). When and why incentives (don’t) work to modify behavior. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(4), 191–210.

Gneezy, U., & Rustichini, A. (2000). A fine is a price. The Journal of Legal Studies, 29(1), 1–17.

Goette, L., Stutzer, A., & Frey, B. M. (2010). Prosocial motivation and blood donations: A survey of the empirical literature. Transfusion Medicine and Hemotherapy, 37(3), 481–502.

Holmås, T. H., Kjerstad, E., Lurås, H., & Straume, O. R. (2010). Does monetary punishment crowd out pro-social motivation? A natural experiment on hospital length of stays. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 75, 261–267.

Kahneman, D., Wakker, P., & Sarin, R. (1997). Back to Bentham? Explorations of Experienced Utility, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(2), 375–405.

Kanbur, R. (2001). On obnoxious markets. Revised version published. In S. Cullenberg & P. Pattanaik (Eds.), Globalization, culture and the limits of the market: Essays in economics and philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2004).

Kelly, D. (2011). Yuck! the nature and moral significance of disgust. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Lee, W., Reeve, J., Xue, Y., & Xiong, J. (2012). Neural differences between intrinsic reasons for doing versus extrinsic reasons for doing: An fMRI study. Neuroscience Research, 73, 68–72.

Lindenberg, S. (2001). Intrinsic motivation in a new light. Kyklos, 54(2/3), 317–352.

Mellström, C., & Johannesson, M. (2008). Crowding-out in blood donation: Was titmuss right? Journal of the European Economic Association, 6, 845–863.

Morishima, Y., Schunk, D., Bruhin, A., Ruff, C. C., & Fehr, E. (2012). Linking brain structure and activation in temporoparietal junction to explain the neurobiology of human altruism. Neuron, 75, 73–79.

Murray, T. H. (1992). The moral repugnance of rewarded gifting. Transplantation & Immunology Letter, 8(1), 5–7.

Paulos, J. A. (2010). He conquered the conjecture, the new york review of books. Retrieved August 21, 2019, from http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2010/04/29/he-conquered-the-conjecture/.

Reiss, S. (2005). Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation at 30: Unresolved scientific issues. The Behavior Analyst, 28, 1–14.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54–67.

Roth, A. E. (2007). Repugnance as a constraint on markets. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(3), 37–58.

Salant, Y., & Rubinstein, A. (2008). (A, f): Choice with frames. Review of Economic Studies, 75(4), 1287–1296.

Sandel, M. J. (2012). What money can’t buy: The moral limits of markets. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Seamone, E. R. (2002). A refreshing Jury Cola: Fulfilling the duty to compensate jurors adequately. Legislation and Public Policy, 5, 289–417.

Suzumura, K. (1999). Consequences, opportunities, and procedures. Social Choice and Welfare, 16(1), 17–40.

Suzumura, K., & Xu, Y. (2001). Characterizations of consequentialism and non consequentialism. Journal of Economic Theory, 101, 423–436.

Suzumura, K., & Xu, Y. (2003). Consequences, opportunities, and generalized consequentialism and non-consequentialism. Journal of Economic Theory, 111(2), 293–304.

Tan, C., & Low, D. (2011). Incentives, norms and public policy. In D. Low (Ed.), Behavioural economics and policy design: Examples from Singapore (Chap. 2, pp. 35–49). World Scientific Publishing Co.

Thøgersen, J. (2003). Monetary incentives and recycling: Behavioural and psychological reactions to a performance-dependent garbage fee. Journal of Consumer Policy, 26, 197–228.

Titmuss, R. M. (1970). The gift relationship: From human blood to social policy. Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

Underhill, K. (2016). When extrinsic incentives displace intrinsic motivation: Designing legal carrots and sticks to confront the challenge of motivational crowding-out. Yale Journal on Regulation, 33(1), 213–279.

Vohs, K., Mead, N. L., & Goode, M. R. (2007). The psychological consequences of money. Science, 314, 1154–1156.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beretti, A., Figuières, C. & Grolleau, G. How to turn crowding-out into crowding-in? An innovative instrument and some law-related examples. Eur J Law Econ 48, 417–438 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-019-09630-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-019-09630-9