Abstract

While customer damage claims against price-cartels receive much attention, it is unresolved to what extent other groups that are negatively affected may claim compensation. This paper focuses on probably the most important one, suppliers to a downstream sellers’ cartel. The paper first identifies three economic effects that determine whether suppliers suffer losses due to a cartel by their customers. We then examine whether suppliers are entitled to claim net losses as damages in the U.S. and the EU, with exemplary looks at England and Germany, delineating the boundaries of the right to damages in the two leading competition law jurisdictions. We find that, while the majority view in the U.S. denies standing, the emerging position in the EU approves of cartel supplier damage claims. We show that this is consistent with the ECJ case law and in line with the new EU Damages Directive. From a comparative law and economics perspective, we argue that more generous supplier standing in the EU compared to the U.S. is justified in view of the different institutional context and the goals assigned to the right to damages in the EU. We demonstrate that supplier damage claims are also practically viable by showing how supplier damages can be estimated econometrically.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Private actions for damages from competition law infringements are on the rise worldwide.Footnote 1 In Europe they are at the heart of the legal and policy debate since the Court of Justice (ECJ) held in Courage thatFootnote 2

The full effectiveness (…) and, in particular, the practical effect of (…) Article [101(1) TFEUFootnote 3] would be put at risk if it were not open to any individual to claim damages for loss caused to him by a contract or by conduct liable to restrict or distort competition.Footnote 4

Five years later, the ECJ added in Manfredi that

(…) any individual can claim compensation for the harm suffered where there is a causal relationship between that harm and an agreement or practice prohibited under Article [101 TFEUFootnote 5].Footnote 6

The ECJ’s holding now also figures in the European directive governing actions for damages for infringements of competition law (EU Damages Directive),Footnote 7 which sets out certain rules “to ensure that anyone who has suffered harm caused by an infringement of competition law (…) can effectively exercise the right to claim full compensation for that harm”Footnote 8 and urges member states to safeguard this right.Footnote 9

The court’s holding that “any individual” has a right to damages strikingly resembles the language in Sec. 4 of the Clayton ActFootnote 10 providing that

(…) any person who shall be injured in his business or property by reason of anything forbidden in the antitrust laws may sue therefor (…) and shall recover threefold the damages (…).

However, the U.S. courts have developed important limitations on standing, whereas the ECJ’s case law, which is the basis of the EU Damages Directive, apparently excludes any outright restriction besides causality. Nonetheless, up to now, the European private enforcement debate has focused almost exclusively on purchasers,Footnote 11 neglecting many other parties that may incur losses due to a sellers’ cartel. This paper focuses on suppliers, a group that is affected particularly often.

While it is accepted that suppliers to a buying cartel (monopsony) are entitled to compensation,Footnote 12 it is mostly overlooked that suppliers to a sellers’ cartel may suffer losses, too.Footnote 13 Whether they have a right to damages for competition law infringements offers insights into how the boundaries of this right are defined in different legal systems. This is important given that, first, private enforcement serves as a policy instrument to discourage infringements,Footnote 14 and second, international cartels usually affect a diverse menu of jurisdictions with different substantive and procedural rules from which potential claimants may be able to choose to a certain extent.Footnote 15

Our analysis starts from the premise that a right to damages by suppliers to a sellers’ cartel requires that, first, suppliers are worse off due to the cartel in economic terms, and that, second, the respective losses, considering the economic mechanisms that produce them, are caught by the law of damages and the law on standing in the legal system at issue.

As to the first condition, Sect. 2 explains analytically that cartel suppliers’ losses are determined by a direct quantity, a price and a cost effect. Concerning the second condition, Sect. 3 analyses whether suppliers are entitled to claim net losses as damages in the U.S. and the EU from a comparative law and economics perspective. We argue that, whereas cartel suppliers are mostly denied a right to damages in the U.S., in the EU the type of loss which the competition provisions are intended to prevent is broader. Importantly, the EU law guidelines on the right to damages are complemented by national law.Footnote 16 We exemplify the interplay of EU law and the law of the Member States by analysing the availability of a right to damages by cartel suppliers in England and Germany, i.e. one common law and one continental law country that currently appear to be among the most popular jurisdictions for follow-on damages actions in the EU.Footnote 17 We also discuss whether and how the English position might change after Britain’s exit from the EU (“Brexit”).

Building on our results, Sect. 4 discusses the case for and against cartel supplier damage claims in Europe, examining whether lessons can be drawn from the U.S. approach. We conclude that the EU institutional framework provides for more generous supplier standing than the U.S. one. This offers a further option to discourage cartels and improve compensation in the EU including England. Refuting the objection that supplier claims would not be practically viable, we sketch an econometric approach based on residual demand estimation that allows to quantify all determinants of cartel suppliers’ damages. We thereby also provide policy advice for the future development of UK competition law post-Brexit.

2 When do cartel suppliers suffer losses?

2.1 Damages in a comparative law and economics context

The law on cartel damages cited in the introduction indicates that there are, roughly speaking, two requirements for a right to damages: First, the potential claimant in question, here the supplier to a sellers’ cartel, must have suffered losses that he would not have incurred absent the cartel. Under a (more) economic approach to competition law,Footnote 18 this requires that effects flowing from a sellers’ cartel make a cartel supplier economically worse off.

In a second step, it is up to legal analysis to determine whether these losses and the economic mechanisms that produce them are caught by the law of damages and the law on standing in the legal system at issue. It should be noted that, in case of an international cartel, claimants may often be able to engage in forum shopping to a certain extent and thereby choose from the affected countries’ different substantive and procedural rules governing actions for damagesFootnote 19: In Europe the Brussels Ia-RegulationFootnote 20—according to a widely shared, though controversial view—usually offers claimants alternative courts of jurisdiction in several Member States.Footnote 21 Building on that, the Rome II RegulationFootnote 22 roughly speaking allows plaintiffs to base their claims against all cartel members on the law of the member state where they file the action.Footnote 23 This legislation has opened up a kind of competition between national fora, the decisive criterion being which one offers the best prospects for claimants.Footnote 24 In case of transatlantic cartels, claimants may furthermore decide to sue in the U.S.Footnote 25 These developments have created a need to compare and evaluate different approaches to standing of “non-standard” cartel victims, of which cartel suppliers are practically most relevant.

2.2 General formal framework

A competition law infringement can be expected to cause, as the U.S. Supreme Court has put it, ripples of harm to flow through the economy,Footnote 26 especially if it occurs in a vertical production chain. A cartel in one market produces numerous effects in the markets up- and downstream.Footnote 27 Direct purchasers pay higher input prices (overcharge) and, by consequence, generally lower their demand. Hence, the cartel members’ sales volume falls. This prompts them to reduce their production and—correspondingly—their input demand. As a consequence, direct suppliers to a sellers’ cartel sell less. The input reductions percolate through the upstream markets, so that the sales of indirect cartel suppliers fall as well.

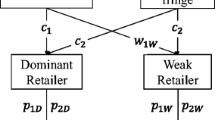

To illustrate, consider a vertical production chain comprising two markets upstream the cartel,Footnote 28 which all have a one-to-one input–output-relation. In the “top” market, m identical firms (indirect cartel suppliers) produce a homogeneous good with constant marginal costs c. They sell it at a unit price q to n identical firms in the second market (direct cartel suppliers). The n firms process the good and sell it at unit price p to identical firms in the third market. Abstracting from additional costs, the selling price q of the m firms in the “top” market equals the marginal costs of the n firms in the second market.Footnote 29 Total industry output is given as

where xi2 and xj1 are quantities of a representative firm i and j in the second and first market, respectively. Total output corresponds to the demand of the firms in the third market. These firms are assumed to initially compete and subsequently collude on their product market, i.e. jointly maximise their profits.Footnote 30 The upstream selling prices are given as q(X) and p(q(X)): The output price in the second market p(q(X)) depends on input costs q(X), which depend on overall quantity X.

Let the equilibrium values under competition be

and under collusion

For simplicity, in what follows we introduce \(p^{*}\) and \(q^{*}\) as shortcuts for \(p(q(X^{*} ))\) and \(q(X^{*} )\) and drop the arguments of the equilibrium values.Footnote 31

The losses two representative firms j and i in the first and the second market incur because of the downstream sellers’ cartel are equal to the difference between their profits under competition and collusion. The respective profits of a representative direct cartel supplier i amount to

Subtracting \({\tilde{{\uppi }}}_{{{\text{i}}2}}\) from \(\pi_{{{\text{i}}2}}^{ * }\) and rearranging parameters yields his lost profits:

Likewise, the profit of a representative indirect cartel supplier j before and after collusion is

yielding cartel induced losses of

Table 1 summarizes supplier damages and decomposes them into three effects, a quantity-, price- and cost effect:

The quantity effect is due to the cartel members’ lower input demand. It equals the difference between the supplier’s sales volumes under downstream competition and collusion, multiplied by his price–cost margin earned under downstream competition.

The price effect equals the difference of the output price under downstream competition and collusion, multiplied by the quantity sold to the downstream cartel members.

The cost effect consists of the difference between the supplier’s marginal costs when producing the output under downstream competition and under collusion, multiplied by the actual sales volume.

Two aspects of this general case should be noted: First, assuming that m = n and \(\tilde{x}_{i2} = \tilde{x}_{j1}\), the price effect of the indirect supplier and the cost effect of the direct supplier exactly match. The direct supplier loses from lower sales but takes advantage of lower input costs. The indirect cartel supplier does not face a cost effect if marginal costs are constant in the top market. Therefore, he or she is more vulnerable to the direct quantity effect.

Second, the number of firms on each upstream market strongly influences suppliers’ damages. Assuming Cournot competition, the direct quantity effect sustained by one cartel supplier is decreasing in the number of symmetric cartel suppliers in the market. As a result, the follow-on effects on prices and costs are also decreasing in the level of competition on the upstream markets.

3 Do cartel suppliers have a right to damages?

Having identified the economic determinants for suppliers’ losses due to a downstream sellers’ cartel, the crucial question is whether these losses and their underlying effects are caught by the law on damages. Naturally, different legal systems may answer this question in different ways, depending on the institutional framework.

3.1 U.S. federal law

3.1.1 General standard

The wording of Sec. 4 Clayton Act cited in the introduction seems to encompass every harm,Footnote 32 but is only superficially clear.Footnote 33 Actually, the U.S. courts have declined to interpret the statute literally.Footnote 34 Over time, a two-pronged approach has developed to limit the universe of potential plaintiffsFootnote 35:

First, the plaintiff must have suffered “antitrust injury”. This requires more than injury in fact, namely “injury of the type the antitrust laws were intended to prevent and that flows from that which makes the defendants’ acts unlawful”.Footnote 36 The requirement connects the plaintiff’s injury to the economic rationale of the antitrust laws.Footnote 37 Its purpose is mainly to inhibit suits that would pervert the antitrust laws into an avenue to dampen competition.Footnote 38

Second, the plaintiff must have standing, that is, he must be considered an efficient enforcer of the antitrust laws.Footnote 39 This requires some analysis of the directness or remoteness of the plaintiff’s injury. The Supreme Court has declined to derive a “black-letter rule” dictating the result in every case, but, building on previous case law, has identified relevant factors. In favour of standing, the court listed a causal connection between the antitrust violation and the harm and defendant’s intent to cause the harm.Footnote 40 The factors militating against standing includeFootnote 41:

-

The plaintiff being neither a consumer nor a competitor in the market in which trade was restrained,

-

indirectness of injury, especially if there are other persons (more) directly affected and better suited to vindicate the public interest in antitrust enforcement,

-

tenuous and speculative character of damages assertedFootnote 42 and

-

potential of duplicative recovery and complex apportionment of damages due to conflicting claims by plaintiffs at different levels of the distribution chain.

3.1.2 Assessment of suppliers

Pursuant to the case law sketched above, suppliers may claim damages if they can prove proximately caused injury-in-fact that can be measured reasonably and constitutes antitrust injury.Footnote 43 The Supreme Court’s “multiple factor test” gives the courts wide discretion to evaluate these criteria.Footnote 44 As a consequence, no consistent body of case law on suppliers to a sellers’ cartel (to be distinguished from suppliers to a buyers’ cartel) has evolved. The question is primarily relevant for direct cartel suppliers. In U.S. federal antitrust law, due to Hanover ShoeFootnote 45 and Illinois Brick,Footnote 46 passing-on arguments are not available. This rule, though developed with respect to cartel purchasers, also bars indirect cartel suppliers from claiming damages.Footnote 47

In practice, the discussion about cartel suppliers mainly centres on employees (i.e. direct suppliers of labour) and (other) direct suppliers attacking mergers of their customers. While the former group is occasionally treated as a normal application of supplier standing,Footnote 48 it has a weaker case. The reason is that the Clayton Act requires injury to “business or property”. A loss of employment or reduction in wages is often considered not to be such injuryFootnote 49 unless the plaintiff’s job is itself a commercial venture or enterpriseFootnote 50 or unless the conspiracy is directed at the employment market.Footnote 51 Therefore, employees, though suppliers of labour, are a special case.Footnote 52

Concerning “ordinary” suppliers seeking redress for losses from an antitrust law violation byFootnote 53 their customers directed at downstream purchasers, most courts as well as leading commentators now deny a right to claim damages. However there is no agreement on the reasons for why this should be so.

Some courts deny standing because the plaintiff and the conspirators do not compete in the market in which trade was restrained. In such a case, the harm is considered indirect and derivativeFootnote 54 and more direct victims the preferred plaintiffs.Footnote 55

Scholars have advanced more elaborate and more nuanced lines of reasoning. Page concedes that cartel suppliers suffer antitrust injury, since the greater the output restriction, the greater the loss of sales by suppliers.Footnote 56 He denies standing, however, arguing that these harms resulted from the violator’s attempt to minimize costs and were entirely offset by a cost saving to the defendant. They were thus caused by a neutral aspect of the violation rather than by the welfare loss to consumers, so that classifying them as damages would cause overdeterrence.Footnote 57 This reasoning is subject to two objections: First, it is imprecise. In the terminology of part II above, only the direct quantity effect and the price effect are pure welfare transfers from suppliers to cartel members, whereas the cost effect, if negative (decreasing marginal costs, e.g. due to economies of scale), may imply welfare losses to society that do not translate into higher prices for cartel customers.Footnote 58 Second, the reasoning raises the question how to justify the departure from the rule that a tortfeasor must indemnify (causal and proximateFootnote 59) damages irrespective of whether they are pure welfare transfers. The fact that certain consequences of an illegal act are welfare transfers seems therefore insufficient to deny a right to damages. One might argue that a deviation can be justified by the goal of U.S. antitrust law being to increase economic efficiency. But this seems doubtful for two reasons. First, it is controversial in U.S. literature whether the U.S. antitrust laws were indeed enacted to increase welfare.Footnote 60 Second, and more important, the efficiency goal as such does not militate against granting damages for welfare transfers. Significantly, consumers may claim the whole overcharge as damages, though the overcharge is a mere welfare transfer.

A more convincing variant of the argument denies antitrust injury. Areeda & Hovenkamp discuss the example of a merger which prompts the partners to increase prices, to reduce output and correspondingly input demand. They argue that, although suppliers suffer a loss from reduced sales due to the reduction in defendant’s output that is the reason for condemning the merger, this effect was “a byproduct of the illegal merger rather than the rationale for making it illegal”. Such a loss fell short of being antitrust injury, as the injury occurred in another market than the lessening of competition that makes a defendant’s conduct illegal.Footnote 61 In view of the foregoing, it is sometimes said that competitors and consumers in the relevant market are presumptively the proper plaintiffs to allege antitrust injury.Footnote 62

3.2 European Union

3.2.1 EU law guidelines

3.2.1.1 Case law

As noted in the introduction, according to the ECJ case law which is now also laid down in the EU Damages Directive, “any individual” must be able to claim compensation for harm causally related to an infringement of EU competition law. This has led to considerable doubts whether traditional restrictions on standing in the laws of the Member States are still tenable.Footnote 63 Several reform initiatives to facilitate actions for damages have followed,Footnote 64 which, as a result, are becoming more common in Europe.Footnote 65

Insofar as EU rules governing the matter are absent, such claims are regulated by the Member States subject to guiding principles of EU law. According to the ECJ, it is for the domestic legal system of each Member State, subject to the principles of equivalenceFootnote 66 and effectiveness,Footnote 67 inter alia to

-

designate the courts and tribunals having jurisdiction and to lay down the detailed procedural rules governing actions for safeguarding EU law rights,Footnote 68

-

prescribe the detailed rules governing the exercise of that right, including those on the application of the concept of ‘causal relationship’,Footnote 69 and to

-

set the criteria for determining the extent of the damages for harm caused by an infringement of European Competition Law,Footnote 70 provided that injured persons can seek compensation for actual loss as well as loss of profit plus interest.Footnote 71

This case law reveals a remarkable tension: On the one hand the apodictic demand to enable “any individual” to claim compensation, on the other hand the apparently great leeway for national law, though now narrowed in certain respects by the EU Damages Directive. Against this background, the fundamental question what characterizes “any individual” that must be able to claim damages is not straightforward to answer. The issue is complicated by the fact that a potential claimant’s right to sue depends, first, on the (minimum) conditions for liability determined by EU law, i.e. the existence of a right to damages, and, second, the exercise of that right pursuant to national law subject to the requirements of the EU Damages Directive and the principles of equivalence and effectiveness.Footnote 72

In this respect, the ECJ’s Kone judgment indicates that the EU law right to damages of any individual adversely affected militates strongly against any inflexible standing limitations apart from technical causality. The case concerned a request for a preliminary ruling under Article 267 TFEU from the Austrian Oberster Gerichtshof in an action for damages by an umbrella plaintiff, ÖBB Infrastruktur. ÖBB claimed that it had bought the cartelized product from non-cartel members at a higher price than it would have paid but for the cartel, on the ground that those third undertakings benefited from the existence of the cartel in adapting their prices to the inflated level.Footnote 73 The ECJ insisted that, while it is, in principle, for the domestic legal system of each Member State to lay down the detailed rules governing actions for damages, national legislation must ensure that EU competition law is fully effective.Footnote 74 The ECJ went on to assert that the full effectiveness of Article 101 TFEU would be put at risk if the right of any individual to claim compensation were subjected by national law, categorically and regardless of the particular circumstances of the case, to the existence of a direct causal link, thereby excluding umbrella plaintiffs.Footnote 75 According to the ECJ, it follows that the victim of umbrella pricing may obtain compensation for the loss caused by the cartel members where it is established that the cartel was, in the specific case at hand, liable to have the effect of umbrella pricing by independent third parties, and that the relevant circumstances and specific aspects could not be ignored by the cartel members.Footnote 76 While the court did not comment on whether these criteria are of general validity, they can readily be applied to any other group of potential claimants suffering from a cartel.

3.2.1.2 Discussion

-

a.

Implications of the case law

The views about the implications of the rather fragmentary case law differ widely, whereas most existing comments predate the Kone judgment. As a starting point, many authors share the view that the ECJ’s demand for “any individual” being able to claim compensation must in principle be taken literally.Footnote 77 Therefore, at least some limitations in the laws of the Member States are considered incompatible with EU law, in particular those based on an alleged ‘protective scope’ of Art. 101, 102 TFEU.Footnote 78 This is corroborated by the Kone case.

Moreover, there is much to suggest that EU law does not permit to refuse damages to all market participants affected indirectly, e.g. via pass-on effects.Footnote 79 The Commission and some commentators even deduce from the Manfredi judgment that indirect purchasers must have standing to sue,Footnote 80 which is now subject to detailed provision in the EU Damages Directive.

However, only few authors conclude that all individuals harmed directly or indirectly by a competition law infringement actually have an EU law based right to damages.Footnote 81 Others stress that the ECJ has accepted certain limitations.Footnote 82 In particular, the ECJ has held that national courts may deny a party damages if that party bears significant responsibility for the distortion of competitionFootnote 83 and/or to prevent unjust enrichment insofar as an infringement produced gains that offset losses.Footnote 84 The latter now also figures in Art. 3(3) of the EU Damages Directive stating that full compensation shall not lead to overcompensation.

Against this background, it is widely accepted, and now also mentioned in a recital of the EU Damages Directive,Footnote 85 that EU law allows to restrict the universe of potential claimants for reasons of remoteness,Footnote 86 which is however a very vague concept. In Kone, Advocate General Kokott did further elaborate on its delineation. She argued that the EU law conditions applicable to the establishment of a causal link are to ensure, first, that a person who has acted unlawfully is liable only for such loss as he could reasonably have foreseen, and that, second, a person is liable only for loss the compensation of which is consistent with the objectives of the provision of law which he has infringed.Footnote 87 Concerning the latter, Advocate General Kokott examined whether awarding compensation for the losses at issue would fit in the EU system of public and private competition law enforcement and whether a damage award would be suitable to correct the negative consequences of the infringement.Footnote 88 However, the ECJ judgment embraces Kokott’s approach only insofar as it briefly mentions the aspect of foreseeability. As to the compatibility with the enforcement system, the ECJ simply—rightly in our view—stated that the leniency programme cannot deprive individuals of the right to obtain compensation for an infringement of Article 101 TFEU.Footnote 89

Apart from remoteness, many other causality defences that might be mounted against a competition law action for damages are in dispute. This holds in particular for the defence that the anti-competitive behaviour is no conditio sine qua non if the injury would have been sustained even in the case of lawful behaviour, and the argument that the victim could have avoided or minimized the damage by taking precautionary action.Footnote 90

-

b.

Application to cartel suppliers

The specific question whether or when cartel suppliers have an EU law based right to damages is rarely dealt with.Footnote 91 Generally, it seems accepted that damage claims may arise if a supplier has to sell his products under less favourable conditions because of a cartel on the demand side,Footnote 92 but authors regularly do not distinguish buyers’ and sellers’ cartels. If they do, they refrain from giving a careful legal assessment with regard to the latter: In particular, the Ashurst study briefly acknowledges damages of suppliers to a sellers’ cartel, but points towards complications with respect to their estimation and the restrictive approach in the U.S.Footnote 93 In a similar vein, the study for the Commission by Oxera & Komninos et al. on quantifying of antitrust damages, starting from the ECJ case law, succinctly lists suppliers as eligible claimants.Footnote 94 Finally, an article by Eger & WeiseFootnote 95 analyzes suppliers damages based on numerical examples in different market situations and points to the problem of how to deal with these damages in the European legal framework. The authors indicate that it might be possible to award damages, but do not discuss the issue further. Similar views, though less pronounced, have been put forward in two leading German competition law journals.Footnote 96

It can thus be said that, while most commentators overlook damages of suppliers to sellers’ cartels, the emerging, but superficially reasoned view is that the concept of “any individual” entitled to damages may encompass suppliers. This is in line with the Commission Staff Working Document accompanying the Communication on quantifying harm in actions for damages based on breaches of Article 101 or 102 TFEU.Footnote 97 It mentions in fn. 26 that other persons “such as suppliers of the infringers (…) may also be harmed by infringements leading to price overcharges”.

3.2.1.3 The EU Damages Directive

The EU Damages DirectiveFootnote 98 harmonizes several procedural issues of private enforcement,Footnote 99 but refrains from regulating the scope of the right to damages as well as the notion of a causal relationship between the infringement and the harm.Footnote 100 According to recital 12, the Directive reaffirms the acquis communautaire on the Union right to compensation for harm caused by infringements of Union competition law, particularly regarding standing and the definition of damage, as it has been stated in the case-law of the Court of Justice of the European Union, without pre-empting any further development thereof. Where Member States provide other conditions for compensation under national law, such as imputability, adequacy or culpability, they are able to maintain such conditions in so far as they comply with the ECJ case law, including the principles of effectiveness and equivalence (recital 11 EU Damages Directive). Consequently Art. 3(1) EU Damages Directive simply repeats the ECJ case law by saying that Member States shall ensure that any natural or legal person who has suffered harm caused by an infringement of competition law is able to claim and to obtain full compensation for that harm, without specifying the group of eligible claimants. Against this background, Art. 12–15 of the EU Damages Directive, regulating the passing-on defence with respect to direct and indirect cartel purchasers as well scenarios “where the infringement of competition law relates to a supply to the infringer” (Art. 12 No. 4), cannot be read to exclude standing of potential claimants other than suppliers of buying cartels. To the contrary, recital 43 of the EU Damages Directive makes clear that the Directive considers a buyers’ cartel to be just one example of cases in which the infringement may also concern supplies to the infringer. In a similar vein the wording of Art. 11(4)(a), (5) sentence 2, (6) EU Damages Directive, mandating an alleviated joint and several liability of immunity recipients, includes “direct or indirect purchasers or providers”. This finding is corroborated by the fact that the Commission, when drafting the original proposal of the Directive, obviously did not intend to restrict the universe of potential plaintiffs with respect to suppliers.Footnote 101

To conclude, the EU Damages Directive is clearly open towards a right to damages for suppliers,Footnote 102 but it neither definitely resolves the question whether cartel suppliers are entitled to damages, nor removes the uncertainties regarding other general EU law issues on standing. At this point the laws of the Member States come into play. In what follows, this is illustrated by current English and German law, which are very popular with damages claimants in the EU.Footnote 103

3.2.2 An exemplary look at two Member States

3.2.2.1 England

-

a.

The current framework

In English law, the claimant’s cause of action for damages for infringement of competition law is nowFootnote 104 normally based on the tort of breach of statutory duty, the statute in question being the European Communities Act 1972 or the Competition Act 1998.Footnote 105 As claims for damages are usually settled, sometimes with considerable payments,Footnote 106 there are almost no final judgments yet that have awarded damages to cartel victims and been upheld on appeal.Footnote 107 However, in two judgments of 2012 and 2013, the CAT has awarded damages to victims of abuses of a dominant position,Footnote 108 and in 2016 the CAT has awarded damages to a victim of an anti-competitive (default) agreement in MasterCard’s electronic payment scheme that operates as a network whose licensees are banks or other financial institutions.Footnote 109

In view of the small body of authoritative case law, it is an open question whether cartel suppliers are entitled to damages for breach of statutory duty.Footnote 110 Two conditions are of critical importanceFootnote 111:

First, it is not sufficient for the claimant to show that the defendant’s breach was a conditio sine qua non, i.e. that the loss would not have occurred but for the breach. Rather, the tortious conduct must have been a cause that, from a normative point of view, is considered material enough to justify damages. This requires that

-

the breach was a substantial, direct or effective cause that cannot be ignored for the purpose of legal liability,Footnote 112

-

the loss was not caused by the claimants own mismanagement or another intervening cause,Footnote 113 which will probably require a supplier to show that the cartel members did not cut supplies from him for other commercial reasons (such as quality), and that

-

the injury is sufficiently proximate.Footnote 114

Second, and probably the crucial hurdle for cartel suppliers, a claimant who sues for breach of statutory duty must in principle show that the duty was owed to him, meaning (1) that the statute imposes a duty for the benefit of the individual harmed, and that (2) the duty was in respect of the kind of loss suffered.Footnote 115 In Crehan v Inntrepreneur Pub Company the defendant raised this issue as a defence before the Court of Appeal, referring—apart from English authorities—to the doctrine of antitrust injury as stated by the U.S. Supreme Court in Brunswick.Footnote 116 The defendant argued that the claimant must also prove that the loss was of a type Art. 101(1) TFEU intended to prevent. The defendant disputed this because Crehan had not suffered from restricted competition in the market for the supply of beer to on-trade outlets, which made the tying arrangement at issue violate Art. 101 TFEU, but from the beer tie distorting competition with other pubs free of tie. The Court of Appeal accepted “as a matter of English law” that the duty breached must be in respect of the kind of loss sufferedFootnote 117 and believed that, for this reason, the “claim cannot succeed in English law alone”.Footnote 118 However, due to the principle of effectiveness, English law must be interpreted such that liability is imposed where required by EU law.Footnote 119 The Court of Appeal therefore rejected the argument in the case at hand, inferring from the ECJ’s preliminary ruling that EU law conferred onto Crehan a right to the type of damages claimed.Footnote 120

The case law thus leaves open whether the English law principle can ever apply in the context of EU competition law.Footnote 121 In any case, the principle cannot be applied narrowly: In particular, the ECJ judgment in Courage shows that a right to damages does not require that the loss occurred in the same market as the illegal restriction of competition. Some commentators conclude that the requirement that the statute imposes a duty for the benefit of the individual harmed is always satisfied in cases involving Art. 101 and 102 TFEU.Footnote 122 Building on this view, others argue that cartel suppliers are entitled to damages for breach of statutory duty.Footnote 123

While breach of statutory duty is a well-established and the most common cause of actions for damages for infringements of competition law, it is not the only one. Sec. 47A of the Competition Act 1998, defining the claims that may be brought before the CAT, is “cause of action-neutral”.Footnote 124 In 2013, the Court of Appeal has confirmed that it possible to advance in the CAT a follow-on claim based on common law conspiracy to use unlawful means.Footnote 125 The unlawful character of the means encompasses infringements (e.g.) of EU competition law.Footnote 126 The tort is committed where two or more persons combine and take action which is unlawful in itself with the intention of causing damage to a third party who does incur the intended damage. The injured party has to prove that causing him damage was part of the combiners’ intentions.Footnote 127 The Court of Appeal in W.H. Newson defined the necessary “intent to injure” quite narrowly, overturning the High Court of Justice that had accepted an “obverse side of the coin argument”.Footnote 128

Insofar as one accepts that cartel suppliers have a right to damages pursuant to English law, this arguably pertains to indirect suppliers. The existence of the passing-on defence has been supported incidentally on a number of occasions in English case law,Footnote 129 but only in 2016 its scope and nature have been ascertained in more detail by the CAT.Footnote 130 The CAT took the EU Damages Directive and U.S. antitrust law into accountFootnote 131 and held that the passing on defence is available in English law as an “aspect of the process of the assessment of damage”.Footnote 132 Later on, the British legislator has followed the lines of this judgment when transposing the EU Damages Directive.Footnote 133 The availability of the passing on defence implies that, conversely, indirect victims are entitled to claim damages.

-

b.

Implications of Brexit

In a referendum that has received much attention worldwide, a majority of the British people have voted in 2016 to withdraw from the European Union (“Brexit”). According to Art. 50 TEU, a Member State which decides to withdraw shall notify the European Council of its intention. The Union shall then negotiate and conclude an agreement with that State, setting out the arrangements for its withdrawal, taking account of the framework for its future relationship with the Union. The Treaties shall cease to apply to the State in question from the date of entry into force of the withdrawal agreement or, failing that, 2 years after the official notification of the intention to withdraw, unless the European Council, in agreement with the Member State concerned, unanimously decides to extend this period.

At the time of writing, it is largely open how a future withdrawal agreement between the UK and the Union will look like. While it appears that the current British Prime Minister Theresa May aims at a complete withdrawal from the EU (“hard Brexit”), other influential members of the government seem to prefer softer options. However, it seems likely that (at least) those Commission decisions and ECJ judgments produced after a future Brexit-agreement will only have persuasive rather than binding effect for the English courts.Footnote 134 Less clear is how existing case law should be treated post-Brexit. Given that English courts and authorities have relied heavily on, and embodied such precedent, the UK might “freeze” the binding precedent value of EU law at the moment of Brexit, with all pre-Brexit judgments remaining binding.Footnote 135 The so called “Great Repeal Bill” published by the UK government in July 2017 arguably chooses this approach.Footnote 136 In any case, the Competition Act 1998 in its current form is closely modeled upon EU competition law.Footnote 137 In particular, the so-called Chapter I prohibition is very similar to Article 101 TFEU.Footnote 138 This makes it likely that for the foreseeable future the CMA and the courts will continue to have regard to EU case law even post-Brexit.Footnote 139

Against this background, the post-Brexit arrangement may or may not have implications for the case law that is relevant for supplier damages: Crehan v Inntrepreneur Pub Company dealt with an infringement of EU competition law. By consequence, as a matter of English law, the only relevant question was whether there are any limits to the type of loss European Competition Law is intended to prevent. In this respect, the Court felt bound by the ECJ’s judgement in Courage.Footnote 140 A similar question arises with respect to British competition law, i.e. when the tort of breach of statutory duty is in question with respect to the Chapter I prohibition or the Chapter II prohibition of the Competition Act 1998. This issue, currently of second order due to the direct application of EU competition law in the UK, will become important after Brexit. As of now, is seems unresolved. As such, the close alignment of UK and EU competition law militates for a parallel interpretation, the more so as the current approach seems well accepted in the UK. Moreover, the English bar as well as the government might be interested in preserving the UK’s position as a popular venue for claims for damages against international cartels.Footnote 141 This position need not suffer from the fact that the Rome II regulation and the Brussels Ia regulation may cease to apply in the UK after a hard Brexit,Footnote 142 but it could be compromised by a more restrictive approach to standing. Besides, as far as the tort of unlawful means conspiracy is concerned, the unlawful character of the means need not follow from English law, but may also follow from foreign law such as EU competition law—a route that will remain open even after a hard Brexit.

3.2.2.2 Germany

-

a.

German law before and since 2005

In Germany, the prospects of suppliers to claim damages changed considerably with the 7th amendment of the German Act against Restraints of Competition (Gesetz gegen Wettbewerbsbeschränkungen, GWB) in 2005. Before the 7th amendment, many lower courts had held that the then-applicable version of the cartel prohibition protected and therefore entitled to damages only those directly aimed at by a competition law infringement (doctrine of the protective purpose, Schutznormtheorie),Footnote 143 thereby excluding suppliers of a sellers’ cartel. However, this interpretation, which has only in 2012 been overruled by the German Federal Court (Bundesgerichtshof, BGH)Footnote 144 was hardly compatible with the ECJ case law since Courage. This prompted a legislative reform.Footnote 145

Since the reform, the GWB provides for a right to damages for every person affected, defined as everybody who, as a competitor or other market participant, is adversely affected by the infringement.Footnote 146 “Other market participants” are defined broadly. The term comprises all natural persons and legal entities that are potentially adversely affected in their market behaviourFootnote 147 by a competition law infringement.Footnote 148 The legislator explicitly intended suppliers to belong to these ‘other market participants’, regardless of whether the cartel deliberately aimed at them.Footnote 149 This seems widely acceptedFootnote 150 and includes direct and—subject to remoteness—indirect suppliers. After much controversy concerning the passing-on defense the German Federal Court (Bundesgerichtshof, BGH) endorsed it in 2012, holding that the group of potential claimants is restricted only by the requirement of a causal link between the illegal cartel and the damages claimed.Footnote 151 With the 9th reform of the GWB, the German legislator has codified the passing-on defense in § 33c GWB new version, in order to comply with the requirements of the EU Damages Directive.Footnote 152

-

b.

Remaining questions

There are thus good reasons to conclude that lost profits of suppliers resulting from an output reduction by the cartel members are in principle recoverable as damages pursuant to German law.Footnote 153 However, it should be noted that some legal uncertainty remains. In particular, according to a view that relies on the government’s statement of reasons (Regierungsbegründung) concerning the reform act of 2005, a market participant is only entitled to damages if there is a more than accidental link, an inner coherence between the reasons that make the defendant’s conduct a competition law violation and the adverse effect on the market participant (so called Zurechnungs- oder Rechtswidrigkeitszusammenhang).Footnote 154 This might be used to exclude cartel suppliers.Footnote 155

Besides, there are doubts whether claims by suppliers are enforceable in practice. Sometimes they are deemed to be speculative in nature and very unlikely to be proven.Footnote 156 In particular, similar to England, the defendant’s action need not only be a conditio sine qua non for the loss (äquivalente Kausalität), but damages must also be attributable to the defendant from a normative point of view (adäquate Kausalität). Besides, a competition law infringement is not considered causal for damages that would have occurred but for the infringement, too.Footnote 157 The supplier must therefore show that the cartel member(s) had bought more inputs just from him (i.e. not from a competing supplier). This task is however alleviated by the legal presumption of lost profits in sec. 252 of the German Civil Code (BGB)Footnote 158 if the supplier could reasonably expect to sell a certain quantity to the cartel members, e.g. because of a stable customer-client relationship.Footnote 159

4 The case for and against cartel supplier standing in the EU

4.1 Lessons from the U.S.?

In view of the open questions concerning the scope of the right to damages for infringements of EU competition law on the one hand, and the considerable experience gained with intense private enforcement in the U.S. on the other, it suggests itself to ask whether the U.S. approach to supplier standing could be a model for private enforcement in the EU.Footnote 160 This crucially depends on the comparability of the framework conditions in the legal systems.Footnote 161

Standing limitations in the U.S. are to a large extent explained by the treble damages remedy. Treble damages, together with opt-out class-actions, pre-trial discovery and contingency fees, make claims for damages very attractive for purported victims, implying a high risk of duplicative recovery and complex apportionment.Footnote 162 In the U.S., it is therefore essential to tightly limit the universe of potential plaintiffs. If, as a collateral consequence, some damages are not recoverable, automatic trebling can in principle make up for such a slippage.Footnote 163 Tellingly, when treble damages are no concern, the U.S. courts adopt a more liberal approach to standing. This holds in particular for sec. 16 of the Clayton Act (15 U.S.C. 26)Footnote 164 which provides for injunctive relief against threatened loss or damage when and under the same conditions and principles as injunctive relief is granted by courts of equity. Insofar the courts are less concerned about whether the plaintiff is an efficient enforcer of the antitrust laws. This is because the dangers of mismanaging them are less pervasive,Footnote 165 given that there is no risk of duplicative recovery and no danger of complex apportionment that both pervade the analysis of standing under sec. 4 Clayton Act.Footnote 166

In a similar vein, even if to a somewhat lesser extent, the risks of duplicative recovery and complex apportionment are less important in the EU compared to the U.S.: First, the EU Member States provide for punitive or exemplary damages only exceptionally.Footnote 167 Second, a loser-pays rule applies to the costs of trial. Third, while providing for certain collective action mechanisms, the EU Member States reject U.S.-style opt-out class actions.Footnote 168 Even the collective proceedings introduced in the UK with the Consumer Rights Act 2015Footnote 169 differ considerably from the U.S. class action system.Footnote 170

In such an institutional framework, only those who suffered significant and provable losses have an incentive to sue for damages. Therefore, in the EU, compared to the U.S., more individuals that might suffer losses from a cartel can confidently be granted a right to damages. In certain respects, this is already current case law. In particular, as Crehan shows, in the EU, unlike in the U.S., a right to damages does not require the loss to occur in the same market than the lessening of competition that makes the defendant’s conduct illegal. It follows that the type of loss which the competition provisions are intended to prevent is broader in the EU than in the U.S.

4.2 The purpose of a right to damages as the guiding principle for standing

The insight that the EU framework allows for more generous standing begs the question how the scope of the right to claim damages should be delimited in the EU. The key to the answer is, in our opinion, to be found in the purpose the legal system assigns to that right. In the U.S., a major purpose of private actions for damages is to deter antitrust law violationsFootnote 171: Private plaintiffs are enlisted as “private attorney generals”Footnote 172 to complement the resources of the antitrust authorities. Such a utilitarian perspective justifies restricting standing to those who can efficiently enforce the antitrust laws, even if this means that some victims remain uncompensated, while others receive windfall profits.Footnote 173 The same result is hard to justify in a legal system like the EU where compensation is a purpose of damages ranking at least equally with and arguably higher than prevention.Footnote 174 In view of this goal, awards should mirror the claimant’s losses as closely as possible, whereas inaccuracy can create injustice.Footnote 175

4.3 The case for supplier standing in the EU

On the basis of the guiding principle just proposed, there are several arguments to suggest that damages of direct suppliers to a sellers’ price cartel should be recoverable pursuant to EU law.

First, as shown above, suppliers regularly suffer losses from a cartel, and thereby come within the scope of “any individual” in the words of the ECJ.

Second, full compensation as a purpose of competition law actions for damagesFootnote 176 requires covering all losses accurately and precisely, as long as no exception is justified. Four possible justifications for exceptions come to mind: (1) remoteness—if damages are remote, litigation is costly and prone to errors that impair prevention (deterrence)Footnote 177; (2) unjust enrichment—in this case the plaintiff would receive a windfall undefendable from a corrective justice point of viewFootnote 178; (3) the victim itself bears significant responsibility for the infringement—then allowing for damages would create an ex-ante incentive to contravene the law; (4) the victim could have easily and cheaply avoided the damage—then allowing for compensation would encourage socially inefficient behaviour.Footnote 179 Neither of these justifications invariably applies to damages of (direct) cartel suppliers. It would therefore seem arbitrary to exclude this group from a right to damages outrightly, contrary to the general principle of equal treatment which requires that comparable situations not be treated differently and different situations not be treated alike unless it is objectively justified.Footnote 180

Third, recognizing suppliers as eligible claimants suits well with the ECJ case law that, notwithstanding the compensatory purpose, assigns the EU law right to damages a preventive purpose, too.Footnote 181 In Kone, the ECJ made clear that national legislation on the right to claim damages, including who can (not) bring a successful claim, must ensure that EU competition law is fully effective. National law must specifically take into account the objective to guarantee effective and undistorted competition in the internal market, and, accordingly, prices set on the basis of free competition.Footnote 182 Advocate General van Gerven has even posited that EU law requires the civil law consequences themselves, in particular the right to damages of any individual, to have a deterrent effect (instead of only contributing to discourage infringements).Footnote 183 Given that not all infringements are detected and that not all victims of detected infringements sue, single damages will arguably only contribute significantly to the prevention of infringements if the class of eligible claimants is not defined narrowly. This suggests that direct and indirect cartel suppliers should in principle have a right to damages.Footnote 184 Such a broad definition of potential claimants would also fit well with ECJ case law in other fields. In particular, the ECJ has enlisted EU citizens as supervisors over the decentralized enforcement of EU law by granting citizens generous standards for standing to sue the Member States for benefits that flow from EU law.Footnote 185

4.4 Objections

While there are thus, in our view, good arguments for granting suppliers of price cartels an EU law based right to damages, there are also counterarguments. We analyze and evaluate them in the following.

4.4.1 Supplier damages reflective?

First, suppliers’ damages from a sellers’ cartel could at first blush considered to be reflective, in the sense of merely mirroring the competition law infringement in relation to cartel customers.Footnote 186 Customers pay higher prices and therefore buy less, the quantity reduction affecting the whole production chain. But this view is too simplistic.

As shown in part II, suppliers primarily suffer a direct quantity effect, reflected in a decrease of sales. This effect will usually not translate into customer damage claims, because those customers priced out of the market (potential customers) are often not able to show and prove damages: End-consumers who did not buy (or bought less) do not even suffer damages in the legal sense, as the law acknowledges only monetary losses or lost profits, not mere losses of utility. At best, cartel customers at intermediate markets of the production chain could claim lost profits if they overcome difficulties of proof.Footnote 187 But when calculating the lost profits of such claimants, their foregone earnings must be reduced by their hypothetical input costs that comprise all profit margins (hypothetically) charged by upstream firms. As a consequence, even if cartel customers claim lost profits with respect to units not bought, their damages do not include the direct quantity effect suffered by suppliers.Footnote 188

Cartel customers primarily claim the overcharge, i.e. the price increase for the units actually produced and sold. With respect to these units cartel suppliers may face a positive or a negative price effect.Footnote 189 (Only) a price decrease (“undercharge”) contributes to suppliers’ damages. By contrast, such an effect does not add to consumer damages: Either the cartel passes on the lower input costs, which then reduce the overcharge and thereby consumer damages, or the cartel retains the decrease in input costs to achieve a higher margin, which again does not increase consumer damages, because the overcharge is calculated with reference to the (input) price under competition.

On the other hand, while the price effect for suppliers fits easily within the basic legal definition of damages—suppliers face losses that would not have occurred but for the cartel, which is a proximate cause (conditio sine qua non)—the price effect mitigates the cartel’s overall negative welfare effects.Footnote 190 From a law and economics perspective, one might therefore advocate accepting only the direct quantity effect, not the price effect, as a component of suppliers’ damages.Footnote 191 However, there are at least two important counter-arguments: First, sticking to the traditional legal notion of damages would increase legal certainty for suppliers’ claims and fit well with the ECJ case law that attaches also a preventive purpose to competition law actions for damages. Second, in view of the fact that cartels cause ripples of harm to flow through the economy, it is not to be expected that all those who suffer from welfare losses actually claim damages. It would therefore not appear convincing to restrict the legal notion of damages for efficiency reasons to the detriment of those who are sufficiently proximate to the cartel and thereby good positioned to bring a claim.

4.4.2 The goal of competition law: Consumer welfare vs. supplier losses?

The argument of supplier damages being merely reflective could at most have some force from a normative perspective if one considers consumer welfare to be the primary goal of EU competition law and—based on this—losses to upper levels of the production chain to be immaterial. However, such a view seems hardly tenable since the ECJ has held in GlaxoSmithKline that Article 101 TFEU aims to protect not only the interests of competitors or of consumers, but also the structure of the market and, in so doing, competition as such.Footnote 192 Therefore, according to the ECJ, for a finding that an agreement has an anti-competitive object, it is not necessary that final consumers be deprived of the advantages of effective competition in terms of supply or price.Footnote 193 Against this background, it cannot be argued that damages to upper levels of the production chain do not matter. Actually, in certain scenarios such as the one in GlaxoSmithKline, awarding non-consumers a right to damages may even be crucial for having private enforcement at all.

4.4.3 Limited protective purpose of EU competition law?

A more substantial counterargument might be to say that, in a normative sense, suppliers of price cartels do not (directly) suffer from decreasing competition. The cartel restricts competition in the selling market to the detriment of its customers, not in the buying market. The harm to suppliers results from the cartel members’ efforts to minimize costs in response to a lower demand for their product. As shown above, in the U.S. a similar reasoning is put forward to deny antitrust injury to suppliers.Footnote 194 While the doctrine of antitrust injury cannot readily be transplanted into competition law regimes with less pervasive private enforcement, the legal systems of the Member States have, as explained on the example of England and Germany, traditionally applied exceptions if damages fall outside the protective purpose of the law forbidding the tortious act. However, many scholars consider such exceptions incompatible with the ECJ case law.Footnote 195 Courage establishes that it is not necessary for the loss to occur in the same market as the lessening of competition that makes a defendant’s conduct illegal. While we do not think that this requires abandoning all kinds of limitations by reason of a protective purpose, neither Courage and Manfredi nor Kone indicate such an exception with respect to the right of any individual to claim damages. Instead, the ECJ defines the scope of potential claimants exclusively by reference to a causal link between the competition law infringement and losses.Footnote 196 From a general tort law perspective, further restrictions seem indeed questionable because price increase and output restriction are inextricably intertwined. A price cartel would not be profitable if the cartel members did not adjust their input demand in view of falling demand for their output. Generally, a tortfeasor is liable for all damages that are inevitable and foreseeable effects of the tort, especially if they are brought about intentionally.Footnote 197 In the European context, unlike the U.S., there are no reasons to privilege cartel members with a more restrictive standard. This view is confirmed by the ECJ’s reasoning in Kone, where the court extends civil liability of cartel members to damages from all (foreseeable) distortions of free competition caused by the cartel. There is much to suggest that this applies irrespective of whether damages occur downstream due to the pricing conspiracy or upstream due to the output restriction. In particular, leaving aside the exceptional scenario of completely inelastic demand, such an output restriction is an inevitable consequence of a downstream price cartel.

4.4.4 Supplier damages cannot be estimated accurately?

The preceding analysis shows that there are good reasons to conclude that cartel suppliers have a EU law based right to damages to be exercised pursuant to national law and EU law requirements. The crucial practical challenge is then to determine the damages in question. This comprises two distinct but related tasks:

First, claimants must be able to obtain data on the infringement that often only the cartel members themselves can provide. A similar problem arises with respect to claims for damages by cartel customers. Traditionally, national procedural laws differ greatly in their propensity to provide for mechanisms like discovery that allow plaintiffs to obtain information from defendants, with common-law-countries being more generous than civil-law-countries. However, the new EU Damages Directive now ensures that claimants in all EU member states have recourse to specific legal means to obtain documents and thereby data from cartel members.Footnote 198 Indeed, claims for damages are brought regularly in the U.S., and in recent times also at an increasing scale in the EU.

Second, one must devise a sound empirical approach that enables victims to prove their losses and courts to sort out unfounded claims with sufficient precision. Concerning the direct quantity effect, it is necessary to estimate a specific suppliers’ decrease in sales volume due to the downstream cartel. This can be done by estimating a residual demand model for this specific supplier that takes the emergence of the cartel into account.Footnote 199 The residual demand function captures the demand a specific supplier faces after the reaction of all other supplier-firms is taken into account. Hence, the residual demand function accounts for the strategic interdependency between competing suppliers, i.e. the fact that a change by one firm prompts the other firms in the same (e.g. supply-)market to adjust their prices.

To illustrate, assume that the demand a cartel supplier i faces in the market for its product (the input for the cartelized good) is given by

Demand depends on the unit price p i firm i charges for its product, a vector p−i of prices charged by all other suppliers-competitors, a vector d of demand shifters and a cartel binary variable C measuring demand changes due to the emergence of a downstream cartel. The first order condition of profit maximization provides the best-reply function of firm i, which denotes the optimal output price for firm i for given prices of all other firmsFootnote 200:

Here, I represents a vector of industry specific cost variables and q i firm specific costs of firm i. Likewise, the vector of best-reply functions of all other firms is given as

Substituting vector (3) into firm i’s demand function (1) yields the residual demand function for firm i:

Note that since prices and quantities are jointly determined, the residual demand function must be estimated with a two-stage-least-squares instrumental variable (IV-) estimation. As firm specific costs of firm i are generally correlated with p i but uncorrelated with the residuals, p i is a suitable instrument for q i .Footnote 201 The econometric implementation of the second stage of an IV-estimation of the residual demand function (4) is then as followsFootnote 202:

\(\widehat{{p_{i,t} }}\) is the estimated price obtained from the first stage IV-estimation,Footnote 203 C t a binary variable equal to one during the cartel period and zero otherwise, and I and \(\varvec{q}_{{ - \varvec{i},\varvec{t}}}\) vectors of exogenous variables that affect industry specific costs (e.g. input costs for the production of the good) and firm specific costs (e.g. capacity utilization) from firms other than firm i. The vector d contains exogenous demand shifters that influence demand for the product independent from the cartel, e.g. purchasing power indices of final consumers.

The approach used to determine the quantity effect is equivalent to the before-and-after method for overcharge estimations. It compares pre- and/or post cartel sales to the sales of the supplier during collusion, on the assumption that the competitive situation in the market but for the cartel would have evolved similarly to the situation before and/or after collusion. The estimation requires data of the respective variables from the cartel period as well as the non-cartel periods.Footnote 204

The average output reduction incurred by the cartel supplier per period during cartelization is now given by the estimated coefficient \(\widehat{{\beta_{2} }}\). The harm associated with the quantity effect (as described in Sect. 2.2) amounts to

The first term sums up the output decreases over the entire cartel period. It is multiplied by the price–cost margin earned by the cartel supplier in the counterfactual competitive scenario.

The price–cost margin can be estimated by means of supplier i’s residual demand elasticity, as we will show during the following analysis of the remaining determinants of a supplier’s overall damage, the price and cost effect.Footnote 205 These effects shown in Table 1 (Sect. 2.2) are given by

which can be rewritten as

Expression (7) corresponds to the difference between the supplier’s price–cost margins under competition and under collusion, multiplied by the quantity sold to the cartel members during collusion. To quantify the price and cost effect, it is therefore necessary to estimate the price–cost margin of the supplier for both regimes. This can be done by means of firm i’s Lerner Index of market power, which relates the firm’s mark-up to the price it charges:

where \(\varepsilon_{i}^{r}\) denotes the residual demand elasticity faced by supplier i in the supplier market. In case of perfect competition in the supply market, the Lerner Index is zero, suggesting that no price and cost effects occur. With increasing market power the Lerner Index increases up to the theoretical maximum value of 1 under monopolization.

We can derive the residual demand elasticities for both periods of time (collusion and non-collusion) by estimating a slightly different version of the residual demand model described above [Eq. (5)]Footnote 206:

The only difference to model (5) is that both quantity and instrumented price of the supplier are in logarithm and that an additional interaction term between instrumented price and cartel-time dummy \(\left( {\widehat{{lnp_{i,t} }}C_{t} } \right)\) is included. The residual elasticity of demand for supplier i during and outside the cartel period is now given as

The estimated demand elasticities in the cartel and the non-cartel period combined with price data of the cartel supplier make it possible to calculate price–cost margins. They can then be used to jointly calculate the price and cost effect as defined in expression (7).Footnote 207 The estimated price–cost margin during the competitive period additionally completes the calculation of the direct quantity effect as stated in (6).

It is worth noting that, depending on the case at hand and data availability, it may be necessary to adjust the estimation approach. Under some circumstances, data restrictions might even allow to estimate the quantity effect only. This is analogous to difficulties that occur when quantifying passing-on effects and output effects in “ordinary” damages estimations for cartel customers. The approach presented here provides a general setting that may be used to quantify the complete supplier’s damage, although sometimes data restrictions or other specific circumstances may restrict its full implementation.

In principle, the approach described in this section could also be applied to a group of firms, for instance a group of (supplier-) claimants. One would then have to treat this group as one single firm in the market and estimate the residual demand for the entire group. However, unlike purchasers who are generally exposed to the same price effect, cartel suppliers might encounter substantially different quantity effects. To illustrate, assume that the cartel members decrease their input demand by 10% due to the infringement. They might then either reduce their input demand by 10% with respect to each supplier, or cut demand to a greater extent or even quit the business relationship with respect to certain suppliers only. In an extreme case, this might even entail a larger input demand from other suppliers in order to receive bulk discounts. Hence, unlike in the case of an average overcharge, it is critical to suppose that a general decrease in residual demand of 10% harms all suppliers equally by a 10% reduction in sales. If this assumption is not warranted, separate estimations for each supplier are preferable.

5 Summary

Private enforcement of competition law is on the rise worldwide and has been on top of the agenda of European competition policy for almost one and a half decades now. However, while actions for damages by cartel customers have received much attention, suppliers to a downstream price cartel have mostly been overlooked so far. Such suppliers incur losses subject to three effects: Cartel members lower sales and correspondingly their input demand (direct quantity effect), which in turn affects the price suppliers can charge for their product (price effect) and their production costs (cost effect).

Whether suppliers are legally entitled to damages for such losses is not straightforward. While the EU and the U.S. both seem to grant damages to “any individual” or “any person” harmed by a cartel, the assessments of supplier damages diverges sharply: In the U.S. the current majority view denies suppliers a right to damages, while the emerging position in the EU is to grant it. In particular, if follows from the case law in Courage v. Crehan that in the EU, unlike in the U.S., a right to damages caused by a competition law infringement does not require the loss to occur in the same market than the lessening of competition that makes the defendant’s conduct illegal. The type of loss which the competition provisions are intended to prevent is therefore broader in the EU than in the U.S., although many details are still open. This affects the laws of the EU Member States that, subject to the EU law principles of equivalence and effectiveness, continue to govern action for damages. Indeed, both Germany and England have abandoned important traditional limitations on standing in order to comply with the ECJ case law. We argue that a more liberal approach to standing is justified in the EU compared to the U.S. in view of the different institutional context and the goals assigned to the right to damages in the EU. Whether English law might change its position after Brexit is currently an open question. Our analysis provides policy advice in the regard. As of now, the law’s causation requirement will be one of the main hurdles to clear for cartel suppliers’ damage claims. In this respect, we show that it is not justified to dismiss such claims as impracticable or speculative, because the damages of a specific supplier can be estimated with a residual demand model that is adjusted for the emergence of a downstream cartel.

Notes

Daniel L. Rubinfeld, in: Elhauge, Research Handbook on the Economics of Antitrust Law, 2012, p. 378.

On the ground-breaking character of this judgment see Alexander Italianer, Public and private enforcement of competition law, 5th International Competition Conference 17 February 2012, Brussels.

At the time of the judgment Art. 85(1) EC.

Case C-453/99—Courage, [2001] ECR I-6297, para 26.

At the time of the judgment Art. 81 EC.

Case C-295/04 to C-298/04, Manfredi, [2006] ECR I-6619, para 61; recently confirmed in Case C-557/12, Kone et al. v ÖBB Infrastruktur, ECLI:EU:C:2014:1317, para 22.

Directive 2014/104/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 November 2014 on certain rules governing actions for damages under national law for infringements of the competition law provisions of the Member States and of the European Union, OJ 5.12.2014, L 349/1 [in the following: EU Damages Directive]. Recital 12 of the EU Damages Directive makes clear that the Directive repeats the case law on standing and the definition of damage.

Art. 1(1) 1 EU Damages Directive.

Art. 3(1) EU Damages Directive.

15 U.S.C. § 15.

In Europe, particular attention has been devoted to the passing on defence, now harmonised by the EU Damages Directive (supra note 7), Art. 12–16 and paras 39–42; see further Magnus Strand, Indirect purchasers, passing-on and the new directive on competition law damages, 10 ECJ 361 (2014). On the previous legal situation in Germany, England and the Netherlands see Anthony Maton et al., The Effectiveness of National Fora for the Practice of Antitrust Litigation, 2 J. Eur. Comp. L. & Prac. 489, 491, 500, 506 (2011). For economic perspectives on the quantification of purchaser damages and the role of a passing-on defense see, e.g. Frank Verboven & Theon Van Dijk, Cartel Damages Claims and the Passing-on Defense, J of Ind Econ, 57(3), pp. 457–491 (2009).

See for the U.S. Phillip E. Areeda & Herbert Hovenkamp, Antitrust law, Vol. IIA, 4th ed. 2014, ¶ 350b p. 268 (majority view of the U.S.-courts, however with occasional aberrant judgments); for the EU cf. the recent EU Damages Directive (supra note 7), paras 38, 43, and generally on the illegality of buying cartels Ariel Ezrachi, Buying alliances and input price fixing: in search of a European enforcement standard, 8 J of Competition Law and Economics 47, 55 et seqq. (2012); Einer Elhauge & Damien Geradin, Global Competition Law and Economics, 2nd ed. 2011, p. 249 et seqq. (for U.S., EU and other nations); for German Law Joachim Bornkamm, in: Langen & Bunte, Kartellrecht, Vol. 1, 12th ed. 2014, § 33, paras 30, 32 et seq., 48; for English law cf. Mark Brealey & Nicholas Green, Competition Litigation, 2010, para 2.02.

There are rare exceptions from an exclusively economic point of view: Thomas Eger & Peter Weise, Some Limits to the Private Enforcement of Antitrust Law: A Grumbler’s View on Harm and Damages in Hardcore Price Cartel Cases, 3 Global Comp. Litigation Rev. 151 (2010) analyze suppliers damages based on numerical examples of price, cost and production functions in different market situations. They point to the problem of how to deal with supplier damages in the legal framework, but offer no further discussion. Besides, Martijn A. Han, Maarten Pieter Schinkel & Jan Tuinstra, The Overcharge as a Measure for Antitrust Damages, Amsterdam Center for Law & Economics Working Paper No. 2008-08, provide a technical economic analysis of cartel damages in a vertical production chain including supplier losses; an economic analysis with a similar focus, but verbally and graphically, can be found in Frank P. Maier-Rigaud & Ulrich Schwalbe, Quantification of Antitrust Damages, in: David Ashton & David Henry, Competition Damages Actions in the EU: Law and Practice, 2013, paras 8.020–8.043; see also the general remarks on quantity effects by Ulrich Schwalbe, Lucrum Cessans und Schäden durch Kartelle bei Zulieferern, Herstellern von Komplementärgütern sowie weiteren Parteien, NZKart 2017, 157–164.

See for the EU C-557/12, Kone et al. v ÖBB Infrastruktur, ECLI:EU:C:2014:1317, para 23; in the U.S., private enforcement is explicitly ascribed the purpose to deter, whereat some argue that deterrence has even priority over compensation, see Daniel A. Crane, in: Hylton (ed.), Antitrust Law and Economics, 2010, p. 2.

See in detail below notes 19–25 and accompanying text.

This continues to be the case after the transposition period of Art. 21(1) EU Damages Directive (supra note 7) has expired on December 27, 2016.

See Commission Staff Working Document, Impact Assessment Report, Damages actions for breach of the EU antitrust rules, Accompanying the proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on certain rules governing actions for damages under national law for infringements of the competition law provisions of the Member States and of the European Union, {COM(2013) 404 final}, Strasbourg, 11.6.2013, para 52: “(…) the vast majority of large antitrust damages actions are currently being brought in 3 European jurisdictions—namely in the UK, followed by Germany and the Netherlands (…).”; in a similar vein Stephen Wisking, Kim Dietzel & Molly Herron, European Commission finally publishes measures to facilitate competition law private actions in the European Union, 35(4) E.C.L.R. 185 (2014).

On this approach, see e.g. the papers in Dieter Schmidtchen, Max Albert & Stefan Voigt (eds.), The More Economic Approach to European Competition Law, 2007, and, in the broader context of the modernization of EU competition law David J. Gerber, Two Forms of Modernization in European Competition Law, 31 Fordham International Law J 1235 (2007).

Brealey & Green (supra note 12), paras 5.02 et seq.; Alison Jones & Brenda Sufrin, EU Competition Law, 4th ed. 2011, p. 1219.

Regulation (EU) No 1215/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December 2012 on jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters (recast), OJ [2012] L 351/1 [in the following: Brussels Ia Regulation].