Abstract

Until the outbreak of the recent economic and financial crisis, Spain was leading the ranking of countries with the largest share of temporary employees. During the crisis this share has fallen to its lowest level in decades, but this does not mean that working conditions in Spain have improved. The flow of new temporary contracts is larger than ever before. A particularly striking feature is the steep growth in the volume of fixed-duration contracts lasting less than a week or a month. We document these trends and analyse how this phenomenon has affected the transition from temporary to permanent employment.

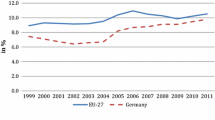

Source: Own elaboration with data from the OECD Employment Protection Database

Source: Spanish Labour Force Survey (EPA, INE) and Estadística de contratos (SEPE)

Source: employed (EPA, yearly averages), contracts (SEPE, total)

Source: Estadística de contratos (SEPE) and the Spanish Labour Force Survey (EPA, INE)

Source: Estadística de contratos (SEPE)

Source: own computations

Source: own computations.

Source: own computations

Source: own computations

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Prior to the 2012 reform, firms could avoid the need to pay interim wages by acknowledging the unfair nature of a dismissal and by paying the worker the corresponding redundancy payment within the first 48 h. The 2012 reform has eliminated this fast-track dismissal procedure, but the parties can still reach the same outcome during the mandatory conciliation phase during which no interim wages are due.

The economic sanctions for the improper use of temporary contracts are independent of the frequency of violations and are often waved once these contracts are converted into open-ended positions.

One example is the need for proportionality between the economic problems of the firm and the number of dismissals. The reform aimed to leave this decision in the hands of employers subject to the new definition of objective causes, but the court rulings have severely restricted this freedom.

The only exception is the period between 2006 and 2008 in which firms were entitled to strong financial incentives for the creation of open-ended jobs.

Individuals may optimally decide not to exercise their right to unemployment benefits or may be unaware of their entitlements. In both cases we are treating the individuals as if they are not entitled.

We could have alternatively used the extreme value distribution. As explained in van den Berg (2001), this distribution allows the model to verify the mixed proportional hazard assumption. Our approach departs from the proportionality assumption, at the cost of imposing more structure, because we want to allow the potential impact of duration and of both observed and unobserved heterogeneity on the exit from employment and unemployment not to be proportional.

Accordingly, two employment spells with the same firm which have an intervening unemployment spell lasting less than 30 days are treated as a single employment spell.

High skill includes college and junior college graduates (groups 1–3 in the Social Security classification), medium-high skill includes top and middle managers (groups 4–6), medium-low skill includes administrative assistants and so-called first- and second-level officers (groups 7 and 8), and low skill includes third-level officers and unskilled workers (groups 9 and 10), see García-Pérez (1997).

As explained before, contributory benefits are measured by the remaining months of entitlement in each month. The latter is computed from each individual’s employment and insurance claim history (since residual benefits not claimed in one unemployment spell can be claimed in a later spell). Workers having access to two different sets of benefit entitlements must choose between them. We assume that they choose the one with the higher length. For more information see Rebollo-Sanz and García-Pérez (2015).

The period “2008–2016” includes the double-dip recession (2008–2013) and the start of the recovery (2014–2016). However, for the sake of brevity we refer to this period as recession.

Results for permanent employment are available from the authors upon request.

We think the proper way to deal with this issue could be the time-to-event approach as developed in de Graaf-Zijl et al. (2011).

Apart from the average survival rates reported in the top row, the survival rates are constructed by varying one characteristic at a time and fixing all other variables at their average value.

To avoid problems of endogeneity we do not include any control related to intermediate spells. Furthermore, the model is estimated without controls for unobserved heterogeneity.

The coefficient estimates are reported in Table 11.

References

Amuedo-Dorantes, C. (2000). Work transitions into and out of involuntary temporary employment in a segmented market: Evidence from Spain. International Labor Relation Review, 53–2, 309–325.

Arranz, J. M., & Garca-Serrano, C. (2014). The interplay of the unemployment compensation system, fixed-term contracts and rehirings: The case of Spain. International Journal of Manpower, 35(8), 1236–1259.

Bentolila, S., Dolado, J. J., & Jimeno, J. F. (2008). Two-tier employment protection reforms: The Spanish experience. CESifo DICE Report 4/2008.

Bentolila, S., Dolado, J. J., & Jimeno, J. F. (2012). Reforming an insider-outsider labour market: The Spanish experience. IZA Journal of European Labour Studies, 1, 4.

Bentolilla, S., García-Pérez, J. I., & Jansen, M. (2017). Are the Spanish long-term unemployed unemployable? SERIEs, 8, 1–41.

Bover, O., Arellano, M., & Bentolila, S. (2002). Unemployment duration, benefit duration and the business cycle. The Economic Journal, 112, 223–265.

Carrasco, R., & García Pérez, J. I. (2015). Employment dynamics of immigrants versus natives: Evidence from the boom-bust period in Spain, 2000–2011. Economic Inquiry, 53–2, 1038–1060.

de Graaf-Zijl, M., van den Berg, G., & Heyma, A. (2011). Stepping stones for the unemployed: The effect of temporary jobs on the duration until (regular) work. Journal of Population Economics, 24(1), 107–139.

Dolado, J. J., Ortigueira, S., & Stuchhi, R. (2016). Does dual employment protection affect TFP? Evidence from Spanish manufacturing firms. SERIEs, 7(4), 421–459.

Felgueroso, F., García-Pérez, J. I., & Jansen, M. (2017). Recent trends in the use of temporary contracts in Spain. Estudios sobre la Economía Española 2017/15, Fedea.

Felgueroso, F., García-Pérez, J. I., & Jansen, M. (2018). La contratación temporal en España: nuevas tendencias, nuevos retos. Papeles de la Economía Española (forthcoming).

García-Pérez, J. I. (1997). Las tasas de salida del empleo y el desempleo en España (1978–1993). Investigaciones Económicas, 21(1), 29–53.

García-Pérez, J. I. (2008). La muestra continua de vidas laborales (MCVL): una guía de uso para el análisis de transiciones. Revista de Economía Aplicada, 16(E–1), 5–28.

García-Pérez, J. I., Marinescu, I., & Vall Castello, J. (2016). Can fixed-term contracts put low skilled youth on a better career path? Evidence from Spain. NBER Working Paper Series, No. 22048 (forthcoming in Economic Journal).

García-Pérez, J. I., & Muñoz-Bullón, F. (2011). Transitions into permanent employment in Spain: An empirical analysis for young workers. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 49(1), 103–143.

Güell, M., & Petrongolo, B. (2007). How binding are legal limits? Transitions from temporary to permanent work in Spain. Labour Economics, 14(2), 153–183.

Heckman, J. J., & Singer, B. (1984). A method for minimising the impact of distributional assumptions in econometric models for duration data. Econometrica, 52, 272–320.

IMF. (2010). Unemployment recoveries during recessions and recoveries: Okun’s Law and beyond. World Economic Outlook, Ch. 3.

Jenkins, S. (1995). Easy estimation methods for discrete-time duration models. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 57(1), 129–138.

Rebollo-Sanz, Y., & García-Pérez, J. I. (2015). Are unemployment benefits harmful to the stability of working careers? The case of Spain. SERIEs—Journal of the Spanish Economic Association, 6(1), 1–41.

van den Berg, G. J. (2001). Duration models: Specification, identification, and multiple durations. In J. J. Heckman & E. Leamer (Eds.), Handbook of econometrics (Vol. 5, pp. 3381–3460). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Figs. 10, 11 and Tables 1, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Felgueroso, F., García-Pérez, JI., Jansen, M. et al. The Surge in Short-Duration Contracts in Spain. De Economist 166, 503–534 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-018-9319-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-018-9319-x