Abstract

Many European Union states have adjusted pension benefits or reformed the pension system in reaction to the recent economic crisis, while other member states have postponed this type of adjustments. In this paper we study to what extent countries that responded quickly to the crisis are harmed by the lingering in other member states via international spillover effects caused by factor mobility and trade. We show that this depends crucially on the degree of labour mobility in the short run. In fact, countries with more flexible pensions can benefit from the inflexibility of pensions in other countries if they can temporarily limit immigration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Usually, in two-country two-goods models, the presence of international trade eliminates the incentives for factor mobility, because interest rates and wages are typically equalized. However, in models with different technologies, factor mobility may reinforce trade after a switch from autarky to an open economy (Razin and Sadka 1992). In our model countries employ the same production functions, but the goods produced in the countries are different. In this setting, asymmetrical pension schemes lead to international factor mobility.

Blonigen and Wilson (1999) estimated the elasticity of substitution for 146 sectors in the United States. The arithmetic average of these estimates is equal to 0.81, with a standard deviation of 0.63, which shows that goods are rather complementary. We therefore employ Armington’s approach for international trade to study the effect of differences in pension policy.

See The local Sweden’s news in English, 26 Jul 2012.

See Financial Times, July 12, 2004.

The robustness of the results for different specifications of the production function and other assumptions is discussed in the “Appendix”.

Throughout the paper, variables without a \(\tilde{}\) refer to the Home country, variables with a \(\tilde{}\) indicate the corresponding variable in the Foreign country. We use lower case to indicate variables in terms of the intermediate good produced in the country and upper case stand for variables in terms of the final good and for the labour force.

Here we have used the fact that the return on savings is equal, irrespective of the country in which savings are invested [see Eq. (16)].

It should be noted that we do not analyse the optimality of the pension policy. In the absence of additional distortions, PAYG pensions only lead to intergenerational redistribution, but not to inefficiency Breyer (1989), Verbon (1989). So a comparison of pension policies can only be based on their redistributive effects using a social welfare function.

Furthermore, the result that the allocation of capital between the economies is constant depends on the way how the composite good is constructed [Eq. (4)]. An alternative functional form of the composition function is discussed in the “Appendix”.

With extreme parameter values (\(\eta \) close to unity for example) it is possible to achieve that the inflexible neighbour leads to lower utility not only for the generations \(t=-1, 0, 1\), but also for generation \(t=2\), but the general result remains the same.

Since, in our model the DC element is larger for the flexible pension schemes, this result is in line with the findings of Bohn (1999), who shows that a pure DC pension system underprotects the old generation, and a pure DB pension system provides too much insurance.

References

Adema, Y., Meijdam, A. C., & Verbon, H. A. A. (2008). Beggar thy thrifty neighbour: The international spillover effects of pensions under population ageing. Journal of Population Economics, 21(4), 933–959.

Adema, Y., Meijdam, A. C., & Verbon, H. A. A. (2009). The international spillover effects of pension reform. International Tax and Public Finance, 16, 670–696.

Armington, P. (1969). A theory of demand for products distinguished by place of production. International Monetary Fund Staff Papers, 16(1), 159–178.

Blonigen, B. A., & Wilson, W. W. (1999). Explaining Armington: What determines substitutability between home and foreign goods? Canadian Journal of Economics, 32(1), 1–21.

Bohn H (1999) Social security and demographic uncertainty: The risk sharing properties of alternative policies. NBER Working Paper 7030.

Börsch-Supan, A., Ludwig, A., & Winter, J. (2006). Ageing, pension reform, and capital flows: a multicountry simulation model. Economica, 73(292), 625–658.

Bouzahzah, M., Croix, D., & Docquier, F. (2002). Policy reforms and growth in computable OLG economies. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 26, 2093–2113.

Breyer, F. (1989). On the international Pareto efficiency of Pay-as-You-Go financed pension systems. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 145, 643–658.

Breyer, F., & Kolmar, M. (2002). Are national pension systems efficient if labor is (im)perfectly mobile? Journal of Public Economics, 83, 347–374.

Colacito, R. (2006). On the existence of the exchange rate when agents have complete home bias and non-time separable preferences. SSRN Working Paper.

Cooper, R., & Kempf, H. (2004). Overturning Mundell: Fiscal policy in a monetary union. Review of Economic Studies, 72(2), 371–396.

Cuñat, A., & Maffezzoli, M. (2004). Hecksher-Ohlin business cycles. Review of Economic Dynamics, 7(3), 555–585.

De Giorgi, G., & Pellizzari, M. (2009). Welfare migration in Europe. Labour Economics, 16(4), 353–363.

Fehr, H., & Kinderman, F. (2009). Pension funding and individual accounts in economies with life-cyclers and myopes. CESifo working paper series. Working paper No: 2724.

Geide-Stevenson, D. (1998). Social security policy and international labor and capital mobility. Review of International Economics, 6(3), 407–416.

Haberis, A., Markovic, B., Mayhew, K., & Zabczyk, P. (2011). Global rebalancing: The macroeconomic impact on the United Kingdom. Bank of England Working Paper No. 421.

Homburg, S., & Richter, W. F. (1993). Harmonizing public debt and public pension schemes in the european community. Journal of Economics. Zeltschrift für Nationalökonomie, 146, 54–63.

Razin, A., & Sadka, E. (1992). International migration and international trade. NBER working paper series. Working Paper No: 4230.

Shiells, C. R., Stern, R. M., & Deardorff, A. V. (1986). Estimates of the elasticities of substitution between imports and home goods for the United States. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 122, 497–519.

Verbon, H. A. (1989). Conversion policies for public pensions plans in a small open economy. In B. Gustafsson & N. Klevmarken (Eds.), The political economy of social security. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Robustness

Appendix: Robustness

The results of the numerical simulations rely on the assumptions about the functional form of the utility function and the production function, as well as on the choice of the parameter values. In this appendix the robustness of the results for changes in these assumptions are discussed.

1.1 The Utility Function

The choice of the log-linear utility function was made for simplicity only. The exact functional form of the utility function is not very important for the results. As long as the utility function satisfies the Inada conditions, changes in lifetime income result in changes in utility, because a higher (net) income allows to reach a higher isoquant curve. Furthermore, also for other specifications of the utility function, more income in the first period of life results in larger savings. But of course, the numerical results may differ if another functional form of the utility function is used. In particular, the speed of convergence of capital presented in Fig. 5 could be different, affecting the speed of convergence of other variables of interest.

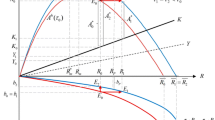

1.2 Composite Goods Technology

The composite goods, which enter as arguments in the utility function are produced using a Cobb–Douglas technology [Eq. (4)]. If a more general function allowing for a constant elasticity of substitution is used, the allocation of capital to the countries described by Eq. (23) would not be constant any more. It would depend on the elasticity of substitution between the goods produced in the countries. If the goods produced in both countries are substitutes, immigration into a country leads to a smaller negative effects on the price, which induces a reallocation of capital to that country. As in this case capital flows follow labour, migration will be larger and thus the positive overshooting in Figs. 7, 8 and 9 can be larger. In the limiting case that the goods produced in the countries are perfect substitutes, the model may produce corner solutions where both labour and capital are concentrated in one of the countries. If the goods produced in the countries are complements, even a small migration flow to a country would lead to a large drop of price of goods produced there, inducing a reallocation of capital to the other country. As a result, the degree of migration would be smaller. However, the direction of the migration flows is unaltered. As the different allocation of capital has a very moderate effect on welfare, the welfare effects remain almost the same for realistic parameter values.

1.3 The Production Function

The effects of using a more general CES form instead of the Cobb–Douglas production function are exactly opposite to those of using a more general function for the composite goods technology. That is, if capital and labour are substitutes, migration to a country would lead to an outflow of capital from it, and if capital and labour are complements, capital an labour move in the same direction. However, the development of the capital stock, which drives most of welfare effects, remains similar to that presented in Fig. 5.

1.4 Fully Inflexible Pensions

If the inflexible country has a completely inflexible pension scheme, i.e., \(\eta = 1\) then in the case of imperfect mobility there is a positive spillover on the generation born at \(t = 0\) only, because at \(t = 1\) the interest rate is higher. However, the spillovers on the generations \(t\ge 1\) are definitely negative, because in this case pension benefits in country F are never reduced and the total amount of capital in the union does not overshoot. With perfectly mobile labour the presence of a completely inflexible neighbour is definitely negative, because it shares all the short run losses with the Home country and does not over-accumulate capital as it does with \(0<\eta <1\). With a large \(\eta \) (but \(\eta <1\)) the inflexible country F may negatively affect more generations, compared to the case discussed, but still after a negative short-run spillover future generations are affected positively.

1.5 Parameter Values

The size of the migration flows depends on the parameter values. In both cases when labour is perfectly and imperfectly mobile, migration is larger when \(\xi \) is smaller, so the pension system is closer to DB, because then migration to country F reduces taxes there and raises taxes in country H more, which makes the Foreign country even more attractive. The case is symmetric for migration to country H. So, in panel b of Fig. 3, large migration to country F at time \(t = 3\) is followed by relatively small migration at time \(t = 4\). In the next period, migration is larger again and so forth. also When mobility is perfect (panel a), the overshooting in migration at time \(t = 2\) is even larger. So a lower value of \(\xi \) leads to a slower convergence to the steady state. However, the direction of migration is the same, and the further results remain unchanged. When \(\xi \) tends to unity, the overshooting disappears and the convergence to the steady state is very fast and monotonic. If \(\xi =1\) and the countries run pure DC pension schemes, migration is smaller but still exists. Different values of the parameters \(\alpha ,\,\rho ,\,\gamma \) and \(\phi \), affect the results quantitatively but not qualitatively.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fedotenkov, I., Meijdam, L. Crisis and Pension System Design in the EU: International Spillover Effects Via Factor Mobility and Trade. De Economist 161, 175–197 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-013-9207-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-013-9207-3