Abstract

Open Access versus Restricted Access in a General Equilibrium with Mobile Capital We consider an economy with two sectors, resource and manufacturing, in a general-equilibrium setting. Two property regimes in the resource sector are compared, open access versus restricted access, with both labor and capital mobility. We first contribute by deriving the multi-factor demand conditions under open access. We provide necessary and sufficient conditions for a factor to gain from a property regime change. Redistributive effects depend crucially on relative factor intensities. Contrary to common wisdom, labor may gain from being “expelled” from the resource sector following privatization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Throughout the analysis, depending on the context or associated literature, terms like “privatization”, “restricted access” or “regulated access” are used interchangeably to represent a managed resource under a property regime to be defined precisely in Sect. 3. This is in opposition to a situation of an unmanaged resource, where terms like “open access”, “free access” or “uncontrolled access” are used. We refrain from using the expression “common property” as it may or may not represent a managed resource, depending on the literature.

The introduction of stock dynamics goes beyond the scope of this paper. It would, however, be straightforward to use our specification and introduce stocks dynamics by assuming period-by-period rent dissipation, as done in Manning et al. (2018) and Squires and Squires and Vestergaard (2013). See Brooks et al. (1999) for a game-theoretic justification of this approach. We leave that for future work.

Finnoff and Tschirhart (2008), Finnoff and Tschirhart (2011) and Deacon et al. (2011) explicitly make use of such a “nested” representation of effective efforts in a CGE model, using a CES technology. Manning et al. (2018) implicitly do the same using a Cobb–Douglas formulation. This in fact only requires the (mild) assumption of homotheticity.

The subscript of a function denotes a partial derivative.

It is straightforward to extend this proposition to any number of inputs or, more generally, to any margin that is left unrestricted.

Note that the excessive use of capital under open access is distinct from the concept of “capital stuffing”, as the latter refers to situations of regulated fisheries (Townsend 1985).

We are grateful to a referee for raising this point as we believe that its consideration contributes greatly to the analysis.

For the case of fisheries, IREPA (2006) estimates annual depreciation rates of 7% for hulls, 25% for engines and 35% for “other equipment”. See also the interesting discussion by Wilen (2009) regarding processing stranded capital arguing that “Most capital involved in fisheries processing is malleable and not likely to be devalued as a result of rationalization”.

This is a consequence of Shephard’s lemma which states that \({\tilde{\mathbf{a}}}^{S}=(c_{i} ^{S}({\tilde{\mathbf{w}}}),c_{j}^{S}({\tilde{\mathbf{w}}}))\). See, for instance, chapter 3 of Woodland (1982).

Note also that if the cost functions were to intersect at multiple points, only one would be compatible with any specific total factor endowment.

Even in 2017 Dean (2017), the New York Times reports on a surprisingly similar situation in Myanmar.

Note that the use of factor income shares as estimators for the parameters of the Cobb–Douglas production function requires that all input uses respect the first-order conditions for profit maximization. This is an unrealistic assumption to make for most developing countries as the land and labor markets are often non-competitive. We understand that it is for this reason that Mundlak, Butzer and Larson (2012) chose to concentrate the discussion on elasticities.

We are grateful to the Editor for raising this point.

The value for \(\theta\) corresponds to an elasticity of substitution of .782.

Note that the problem is undefined for \(\xi _{i}(\mathbf {x}^{M})=\xi _{i}(\mathbf {x}^{R})\).

References

Abbott JK, Wilen JE (2009) Rent dissipation and efficient rationalization in for-hire recreational fishing. J Environ Econ Manag 58:300–314

Ambec S, Hotte L (2006) On the redistributive impact of privatizing a resource under imperfect enforcement. Environ Dev Econ 11:677–696

Anderson TL, Hill PJ (1983) Privatizing the commons: an improvement? Southern Econ J 50:438–450

Baland J-M, Francois P (2005) Commons as insurance and the welfare impact of privatization. J Publ Econ 89:211–231

Brander JA, Taylor MS (1997) International trade and open access renewable resources: the small open economy case. Can J Econ 30(3):526–552

Brito DL, Intriligator MD, Sheshinski E (1997) Privatization and the distribution of income in the commons. J Publ Econ 64:181–205

Brooks MA, Heijdra BJ (1990) Rent-seeking and the privatization of the commons. Eur J Polit Econ 6:41–59

Brooks R, Murray M, Salant S, Weise JC (1999) When is the standard analysis of common property extraction under free access correct? a game-theoretic justification for non-game-theoretic analyses. J Polit Econ 107(4):843–858

Campbell BMS, Bartley KC, Power JP (1996) The demesne-farming systems of post-black death england: a classification. Agric Hist Rev 44(2):131–179

Caselli F (2005) Accounting for cross-country income differences. In: Aghion P, Durlauf SN (eds) Handbook of economic growth, vol 1A, chapter 9. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 679–741

Cheung SNS (1970) The structure of a contract and the theory of a non-exclusive resource. J Law Econ 13:45–70

Chichilnisky G (1994) North-south trade and the global environment. Am Econ Rev 84(4):851–874

Cohen JS, Weitzman ML (1975) A Marxian model of enclosures. J Dev Econ 1:287–336

Copeland BR, Taylor MS (2009) Trade, tragedy, and the commons. Am Econ Rev 99:725–49

Daintith T (2010) Finders keepers? how the law of capture shaped the world oil industry. Resources for the Future Press, Washington, DC

Dasgupta PS, Heal GM (1979) Economic theory and exhaustible resources. James Nisbet and Co., Ltd and Cambridge University Press, Welwyn

de Meza D, Gould JR (1987) Free access versus private property in a resource: income distributions compared. J Polit Econ 95(6):1317–1325

Deacon RT, Finnoff D, Tschirhart J (2011) Restricted capacity and rent dissipation in a regulated open access fishery. Resour Energy Econ 33:366–380

Dean A (2017) Drilling for a dream in Myanmar. The New York Times, New York

Finnoff D, Tschirhart J (2008) Linking dynamic economic and ecological general equilibrium models. Resour Energy Econ 30:91–114

Finnoff D, Tschirhart J (2011) Inserting ecological detail into economic analysis: agricultural nutrient loading of an estuary fishery. Sustainability 3:1688–1722

Gollin D (2002) Getting income shares right. J Polit Econ 110:458–474

Gordon HS (1954) The economic theory of a common-property resource: the fishery. J Polit Econ 512:124–142

Hotte L, Van Long N, Tian H (2000) International trade with endogenous enforcement of property rights. J Dev Econ 62:25–54

IREPA (2006) Evaluation of the capital value, investments and capital costs in the fisheries sector. In: Report FISH/2005/03. Institute for Economic Research in Fishery and Acquaculture

Jones RW (1971) A three factor model in theory, trade and history. In: Bhagwati J, Jones RW, Mundell R, Vanek J (eds) Trade, balance of payments, and growth. North-Holland, Amsterdam

Karp L (2005) Property rights, mobile capital, and comparative advantage. J Dev Econ 77:367–387

Libecap GD, Wiggins SN (1984) Contractual responses to the common pool: prorationing of crude oil production. Am Econ Rev 74:87–98

Manning DT, Edward TJ, Wilen JE (2014) Market integration and natural resource use in developing countries: a linked agrarian-resource economy in northern honduras. Environ Dev Econ 19:133–155

Manning DT, Edward TJ, Wilen JE (2018) General equilibrium tragedy of the commons. Environ Resour Econ 69:75–101

Mayer W (1974) Short-run and long-run equilibrium for a small open economy. J Polit Econ 82:955–967

Mundlak Y, R Butzer, Larson DF (2012) Heterogeneous technology and panel data: the case of the agricultural production function. J Dev Econ pp 139–149

Mussa M (1974) Tariffs and the distribution of income: the importance of factor specificity, substitutability, and intensity in the short and long run. J Polit Econ 82:1191–1204

Samuelson PA (1974) Is the rent-collector worthy of his full hire? East Econ J 1:7–10

Sokoloff KL, Engerman SL (2000) History lessons: institutions, factor endowments, and paths of development in the new world. J Econ Perspect 14:217–232

Squires D, Vestergaard N (2013) Technical change and the commons. Rev Econ Stat 95(5):1769–1787

System of National Accounts (2008) United Nations, European Commission, Organisation for economic co-operation and development, International Monetary Fund and World Bank Group, New York

Townsend RE (1985) On “capital-stuffing” in regulated fisheries. Land Econ 61(2):195–197

Weil D (2013) Economic growth, 3rd edn. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River

Weitzman ML (1974) Free access vs private ownership as alternative systems for managing common property. J Econ Theory 8:225–234

Wilen JE (2009) Stranded capital in fisheries: the pacific coast groundfish/whiting case. Mar Resour Econ 24:1–18

Woodland AD (1982) International trade and resource allocation. North-Holland Publishing Company, Amsterdam

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This paper has benefited from comments by Stefan Ambec, Brian Copeland, Pierre Lasserre, Martin Weitzman and seminar participants at the University of Ottawa, Université de Rouen, the CREE Meetings, the Conference on Environment and Natural Resources Management in Developing and Transition Economies at Université d’Auvergne, the Montreal Natural Resources and Environmental Economics Workshop, Economix at Université Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense, the School of Economics at the University of Queensland and the Congreso Sobre México at Universidad Iberoamericana.

Appendices

Appendix A: Self-employment and Cost-Minimization Under an Open-Access Regime

In this section, we show that cost minimization occurs under open access with self-employed users/workers, as long as they are free to move between the sectors.

Let n denote the total number of workers exploiting the resource. (We keep this number fixed for now. It will be made endogenous below.) \(z_j=F^R(x^R_{lj},x^R_{kj})\) denotes the effective effort expended on the resource by worker j, \(j\in \{1,2,\ldots ,n\}\). The total effort expended on the resource is thus given by \(z=\sum _{j=1}^{n}z_j\), which yields total output f(z) and average product of effort \(\phi (z)\). Suppose, to simplify, that a worker inelastically supplies one unit of labor and that she cannot split her time between the manufacturing and the resource sector. We have \(x^R_{lj}=1\), \(\forall j\), and individual effort is thus uniquely determined by a worker’s choice of capital input \(x^R_{kj}\) at cost \(w_k\). We now turn to this choice.

Worker j’s net payoff from the resource is given by

where \(z_j=F^R(1,x^R_{kj})\). Now if n is large enough—as must be the case under open access over a large resource site—each resource worker will take \(\phi (z)\) as given when deciding on her individual effort level.Footnote 17 The first-order condition for j’s choice of capital is thus:

This condition has the same interpretation as the one provided above for conditions (12). Now with constant returns to scale, we have \(F_k^R\left( 1,x^{R*}_{kj}\right) =F_k^R\left( n,x^{R*}_{k}\right)\), where \(x^{R*}_{k}=nx^{R*}_{kj}\). Consequently, for a given number of workers, the equilibrium total amount of capital hired on the resource site is given by:

For the case of capital, we therefore have the same condition as in (12). Given n, this condition determines the equilibrium total and individual efforts being supplied, respectively \(z^*\) and \(z^*/n\), along with the corresponding equilibrium individual net payoff \(\pi ^*=(p\phi (z^*)z^* - w_k x^{R*}_{k})/n\). Let us now turn to the determination of n.

Given that workers are free to move between the sectors, the equilibrium allocation of workers between manufacturing employment and resource exploitation must be such that they are indifferent between them. This requires that \(\pi ^*=w_l\). Given that the prevailing wage \(w_l\) in the manufacturing sector must be regarded as the true opportunity cost of workers exploiting the resource, this last condition implies total rent dissipation, i.e., \(p\phi (z^*)z^* =w_ln + w_k x^{R*}_{k}\). This leads to the following proposition:

Proposition 6

With self-employed resource users who are free to move between the sectors, the open-access equilibrium is equivalently characterized by conditions (12).

Proof

The case with \(i=k\) has already been derived as condition (26) above. We now derive the case for \(i=l\). Because \(F^{R}(\mathbf{x} ^{R})\) has constant returns to scale, we have \(z=x^R_lF^R_l+x^R_kF^R_k\). Substituting (26), this gives \(z=x^R_lF^R_l+w_kx^R_k/p\phi (z)\) or, equivalently, \(p\phi (z)z=p\phi (z)x^R_lF^R_l+w_kx^R_k\). Making use of the above total rent dissipation result, this implies that \(p\phi (z)x^R_lF^R_l+w_kx^R_k=w_lx^R_l + w_k x^{R}_{k}\), where \(x^R_l\) substitutes for n. This simplifies to \(p\phi (z)F^R_l=w_l\). \(\square\)

Appendix B: Proof that \(c^{R}({\hat{\mathbf{w}}})\le c^{R}({\tilde{\mathbf{w}}})\)

Recall that equilibrium conditions for factor payments must respect condition (6) and either of (11) or (10). Let us express those by the following set of two equations, where parameter \(\alpha\) is either equal to \(p\phi (\tilde{z})\) or \(pf^{\prime }(\hat{z})\):

Differentiating these two expressions with respect to parameter \(\alpha\) and making use of Cramer’s rule yields:

Now according to Shephard’s lemma, \(c_{i}^{S}\) denotes the quantity of factor i used in sector S per unit of output, i.e., \(y^{S}c_{i}^{S}=x_{i}^{S}\), \(S\in \{M,R\}\), and similarly for factor j. Inserting this into the above two equations yields:

We consequently have:

Without loss of generality, we posit that \(\xi _{i}(\mathbf {x}^{M})>\xi _{i}(\mathbf {x}^{R})\).Footnote 18 The above therefore implies that an increase in \(\alpha\) leads to a decrease in \(w_{i}/w_{j}\).

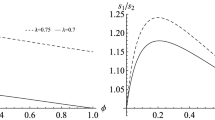

Assume now that \(c^{R}(\hat{w})>c^{R}(\tilde{w})\). This implies that \(\alpha\) must take on a larger value under RA than OA and thus, according to the above result, \(\hat{w}_{i}/\hat{w}_{j}<\tilde{w}_{i}/\tilde{w}_{j}\). But \(c^{R} (\hat{w})>c^{R}(\tilde{w})\) also implies that \(\hat{z}<\tilde{z}\), as can be readily seen from Fig. 2. Now according to Corollary 2, \(\xi _{i}(\mathbf {x}^{M})\ge \xi _{i}(\mathbf {x}^{R})\) implies \(\hat{w}_{i}/\hat{w}_{j}\ge \tilde{w}_{i}/\tilde{w}_{j}\) when \(\hat{z} <\tilde{z}\). A contradiction. \(\square\)

Appendix C: Proof that \(\hat{z}<\tilde{z}\)

Assume to the contrary that \(\hat{z}\ge \tilde{z}\). Then, it must be the case that \(c^{R}(\hat{w})<c^{R}(\tilde{w})\). In line with the analysis of Appendix 1 above, this calls for a lower value of \(\alpha\) under RA as compared to OA and therefore \(\hat{w}_{i}/\hat{w}_{j}>\tilde{w}_{i}/\tilde{w}_{j}\). Consequently, factor i is used less intensively under RA than OA and, as can be readily seen in Fig. 1, this requires \({\hat{\mathbf{x}}}^{R}\ll {\tilde{\mathbf{x}}}^{R}\) and thus \(\hat{z}<\tilde{z}\). A contradiction. \(\square\)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Congar, R., Hotte, L. Open Access Versus Restricted Access in a General Equilibrium with Mobile Capital. Environ Resource Econ 78, 521–544 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-021-00542-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-021-00542-4

Keywords

- Property rights

- Natural resources

- Open access

- General equilibrium

- Mobile capital

- Factor payments

- Factor intensities

- Income distribution