Abstract

Due to differences in information disclosure mechanisms, consumer misinformation about the quality of many credence goods is more endemic at intermediate levels of the quality spectrum rather than at the extremes. Using an oligopoly model of vertical product differentiation, we examine how consumers’ overestimation of the quality of intermediate-quality products affects firms’ incentives to improve product quality. The firms non-cooperatively choose the quality of their product before choosing its price or quantity. Irrespective of the nature of second stage competition, Bertrand or Cournot, we find that quality overestimation by consumers increases profit of the intermediate-quality firm, and motivates it to raise its product’s quality. In response, the high-quality firm improves its product quality even further but ends up with lower profit. Overall, average quality of the vertically differentiated product improves, which raises consumer surplus. Social welfare increases when the firms compete in prices but falls when they compete in quantities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For environmental labelling, these correspond to the International Standards Organization’s ISO 14024 (or “Type I”) and ISO 14021 (or “Type II”) standards, respectively. Such disclosure strategies that involve public or private endeavours to increase the availability of information on polluting goods have been called the “third wave” in environmental policy, with standards and market-based instruments constituting the first two waves (Tietenberg 1998).

To varying extents, instances of “greenwashing” happen even in those countries where there are truth-in-advertising regulations. For e.g., the Canadian Competition Bureau enforces the misleading advertising and labeling provisions in Canadian law that “prohibit making any deceptive representations for the purpose of promoting a product or a business interest, and encourage the provision of sufficient information to allow consumers to make informed choices” (http://www.competitionbureau.gc.ca/eic/site/cb-bc.nsf/eng/02776.html). Nevertheless, misleading advertising remains commonplace in Canada partly due to difficulties in enforcing the law. For instances, see CBC’s program on top ten misleading labels: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/10-misleading-food-product-labels-in-canada-1.1142301. The program suggests that both producers and consumers share responsibility for consumers’ misjudgements about product quality while shopping. When firms sell branded products that are similar in functionality and price in intensely competitive markets, they have a tendency to play up their product differentiation along dimensions such as environment or labour friendliness. Shoppers who have little time or knowledge, but have to decide which brand to purchase from a multitude of similar alternatives, often end up buying the affordable brand that conveys, even if vaguely, that an effort has been made to make it a better product.

For example, while most conventionally raised egg-laying hens are kept in cages, a USDA report notes that the cage-free label “does not guarantee that the bird had access to the outdoors” (Oberholtzer 2006, p. 6). The cage-free label is unregulated and does not require third-party certification. Similarly, the term “local” is interpreted differently by retailers to label food products. In the United States, Walmart labels food that is produced within a state’s borders as “local”, while Whole Foods uses this term for food that has travelled less than a day from farm to store (Martinez 2010).

Conversely, since it has a detrimental impact on their profits, firms have an incentive to proactively counter any misinformation that makes consumers underestimate their product quality. In their survey involving 2511 consumers in the U.S. and Canada, Campbell et al. (2015) find that only 10–15 % of the respondents perceive the unregulated labels “eco-friendly” and “sustainable” as a marketing gimmick used by producers.

MQSs may involve the banning of harmful processes or inputs in the production of goods, e.g. child labour, lead paint in toys, carcinogenic additives to food, etc.

A New York Times report refers to natural as a “slippery word”; see “When it comes to meat, ‘natural’ is a vague term,” New York Times, 10 June 2006. Bernard et al. (2013) report similar examples of consumer misinformation with respect to self-labels used by the apparel and textile industry. Campbell et al. (2015) find that consumers tend to misperceive the unregulated labels “eco-friendly” and “sustainable”, and conflate them with the regulated “organic” label.

For details, see USDA’s National Organic Program website http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/nop.

In those industries where firms choose their capacities and production before the determination of the market-clearing price, it can be assumed that firms compete in quantities. Conversely, in industries where capacity constraints are less important and production can be quickly adjusted, it is more relevant to assume that firms compete in prices (Kreps and Scheinkman 1983). While price vs. quantity competition often leads to starkly different theoretical results, the empirical literature has relied more on results that are invariant across different classes of models, such as Cournot and Bertrand, that often cannot be distinguished empirically (Sutton 1997; Valletti 2000).

While firms in duopolistic markets differentiate their products excessively in the first stage in order to reduce market competition in the second stage, this over-differentiation result almost entirely disappears when there are three or more firms in the market (Schmidt 2009).

The literature broadly classifies advertising into three types: persuasive, informative, and complementary (see the survey by Bagwell 2007). Persuasive advertising seeks to change consumers’ preferences in favour of the advertised products by artificially differentiating these products even when there are no substantive differences.

Methodologically, our analysis relates to the literature on minimum quality standards (e.g. Ronnen 1991; Crampes and Hollander 1995; Scarpa 1998; Valletti 2000; Pezzino 2010). Using oligopoly models of vertical product differentiation, this literature examines the impacts of exogenous increases in minimum permissible quality on the qualities chosen by higher quality firms and on social welfare.

While we do not endogenize misinformation in this paper, a theoretical justification for why there can be more misinformation at intermediate levels of quality is as follows. Suppose the range of quality is known to be discrete and bounded between a lower and an upper limit. Consumers get a signal about the true quality of products via product labels. For the lowest quality, a misleading signal can only tell consumers that quality is better than it actually is, while for the highest quality, the signal can only tell consumers that it is worse. However, for intermediate qualities the signal can be lower or higher than the true quality. Thus, the signal is likely to have more variance, and hence be less informative, for intermediate levels of quality than for very low or very high ones. We thank a referee for suggesting this theoretical justification.

As noted by Motta (1993), \(\theta \) can be interpreted as the marginal rate of substitution between income and quality, so that a higher value of \(\theta \) corresponds to a lower marginal utility of income and thus a higher level of income. As such, our model is similar to models where consumers differ by income rather than by taste.

In the model, we assume that misinformation affects all consumers equally. Alternatively, misinformation could affect a fraction x of the consumers (the “uninformed”) and make them overestimate the quality of the natural good, while fraction \((1-x)\) could be correctly informed about quality (the “informed”). As long as the uninformed consumers have the same distribution of taste parameter \(\theta \) as the informed, the two alternative ways of modeling misinformation will be equivalent. That is, a decrease in \(\beta \) in our model will yield qualitatively similar results as an increase in x in the alternative way of modeling misinformation.

Note from (1) and (6)–(8) that \(q_b >0\) if and only if \(\beta >(p_b s_n )/(p_n s_b ), q_g >0\) if and only if \(\beta >s_n /(s_g +p_n -p_g )\), and \(q_n >0\) if and only if \(\beta <s_n (p_g -p_b )/(s_g (p_n -p_b )+s_b (p_g -p_n ))\). In the equilibrium derived in Sect. 3, we find that all three quantities are positive when \(\beta \in (s_n /s_g ,1)\), as assumed in the paper.

This may happen in the short run if prices are determined via costs in a perfectly competitive market, and costs and quality levels are in turn dependent on existing technology.

Our supply side assumptions are similar to those in Ronnen (1991), Scarpa (1998), Valletti (2000) and Pezzino (2010). Like them we assume that the burden of quality improvement falls disproportionately on fixed costs (e.g. more expenditure on R&D or capital) rather than variable costs (e.g. more expensive raw materials).

Quality improvement, rather than the creation of misinformation, is the costly activity that is the long run choice variable for the firms in our model. When the natural firm increases the true quality of its product by adding more desirable attributes, it is able to raise consumers’ perceived quality as well through misleading self-labels or claims at negligible additional cost. Further, \(\tilde{s}_n \) and \(s_n \) are multiplicatively related through \(\beta \) in our model. Even if \(\tilde{s}_n \) and \(s_n \) were related in an alternative manner, e.g. additively, our results would remain qualitatively unchanged.

In equilibrium, we find that \({ CS }_{perceived} >{ CS }_{actual} \). While measuring consumer surplus using actual rather than perceived quality, Glaeser and Ujhelyi (2010, p. 250) note that, “When advertising is misleading, it seems sensible to measure consumer surplus based on the true health costs of the product.” Similarly, Hattori and Higashida (2012, p. 1162) state that, “Because the advertising is misleading, consumer surplus should be measured based on the true quality of the products.” Both the papers also use actual consumer surplus to evaluate social welfare.

For e.g., the long term health impacts of processed food that contains excessive sugar, salt or fat may not be adequately appreciated by consumers when they purchase or consume them. Similarly, consumers may overestimate the benefits of many health and wellness products, e.g. “probiotic” yogurt, sold in the market.

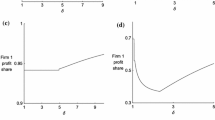

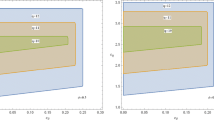

The computations are done, using the software Mathematica, for all values of \(\beta \in (0,1]\) starting from 1 and decreasing in increments of 0.01. Note that the misinformation parameter \(\beta \) is the only parameter in our model.

The equilibriums for additional values of \(\beta \) are reported in our working paper, Baksi et al. (2012). Table 1 shows that for \(\beta =1\) the equilibrium qualities are \(s_b^*=0.0095, s_n^*=0.0497\) and \(s_g^*=0.2526\). In this special case, when consumers do not overestimate quality, our model and equilibrium coincide with those in Scarpa (1998, p. 669).

While the sign of \(ds_i^*/d\beta \) shows how \(s_i^*\) changes when \(\beta \) decreases, explicitly solving for the equilibrium values of \(s_n^*(\beta )\) and \(s_g^*(\beta )\) allows us to check that in equilibrium we have \(\beta >s_n^*(\beta )/s_g^*(\beta )\), as assumed in the model.

Note that when \(\beta =1\), our Cournot equilibrium coincides with the unregulated equilibrium in Pezzino (2010, p. 31), and the product qualities are \(s_b^{**} =0.0261, s_n^{**} =0.0894\) and \(s_g^{**} =0.2522\).

Table 3 shows that, in both the Bertrand and Cournot equilibriums, the direct effect of a marginal decrease in \(\beta \) is to increase the profitability of quality for the natural firm. However, the table also shows that the effects of marginal changes in \(s_i \) on the first stage reaction functions can be qualitatively different for price versus quantity competition. For instance, a marginal increase in quality of the brown good increases (decreases) the profitability of quality for the natural firm and decreases (increases) the profitability of quality for the green firm in the Bertrand (Cournot) equilibrium. Moreover, a marginal increase in quality of the green good increases (decreases) the profitability of quality for the brown and the natural firms in the Bertrand (Cournot) equilibrium.

However every consumer may not benefit due to greater misinformation. Consider the following comparative statics involving two equilibriums, A and B, with increasing consumer misinformation so that the value of \(\beta \) decreases from \(\beta ^{A}\) to \(\beta ^{B}\). In equilibrium A, the consumer who is indifferent between not purchasing the good and purchasing the brown type is given by \(\theta _1^A =p_b^A /s_b^A \). This marginal consumer obtains zero surplus from consuming the brown good. In equilibrium B, consumption of the brown good gives the same consumer a surplus of \(\theta _1^A s_b^B -p_b^B =s_b^B \left( {\frac{p_b^A }{s_b^A }-\frac{p_b^B }{s_b^B }} \right) =s_b^B \left( {\theta _1^A -\theta _1^B } \right) \). Thus, the consumer with taste parameter \(\theta _1^A \) gains from an increase in misinformation when the quality-adjusted price of the brown good \(p_b /s_b \) decreases (as in the Bertrand case). By contrast, when \(p_b /s_b \) increases due to a decrease in \(\beta \) (as in the Cournot case), the consumer \(\theta _1^A \) drops out of the market and market coverage decreases. This implies that the increase in misinformation adversely affects a few inframarginal consumers with low values of \(\theta \) in the Cournot case, even though it benefits consumers as a whole.

If the consumers were to underestimate the quality of the intermediate-quality product in our model, this would reduce the natural firm’s demand and incentive to invest in quality, and lead to the opposite results.

References

Abrams K, Meyers C, Irani T (2010) Naturally confused: consumers’ perceptions of all-natural and organic pork products. Agric Hum Values 27(3):365–374

Amacher G, Koskela E, Ollikainen M (2004) Environmental quality competition and eco-labeling. J Environ Econ Manag 47:284–306

Bagwell K (2007) The economic analysis of advertising. In: Armstrong M, Porter R (eds) Handbook of industrial organization, vol 3. North-Holland, Amsterdam, pp 1701–1844

Baksi S, Bose P (2007) Credence goods, efficient labelling policies, and regulatory enforcement. Environ Resour Econ 37:411–430

Baksi S, Bose P, Xiang D (2012) Credence goods, consumer misinformation, and quality. Department of Economics Working Paper 2012-01, University of Winnipeg. https://ideas.repec.org/p/win/winwop/2012-01.html

Becker G, Murphy K (1993) A simple theory of advertising as a good or bad. Q J Econ 108(4):941–964

Bernard J, Hustvedt G, Carroll K (2013) What is a label worth? Defining the alternatives to organic for US wool producers. J Fash Mark Manag 17(3):266–279

Campbell B, Khachatryan H, Behe B, Dennis J, Hall C (2015) Consumer perceptions and misperceptions of ecofriendly and sustainable terms. Agric Resour Econ Rev 44(1):21–34

Crampes C, Hollander A (1995) Duopoly and quality standards. Eur Econ Rev 39:71–82

Darby M, Karni E (1973) Free competition and the optimal amount of fraud. J Law Econ 16(1):67–88

Dixit A, Norman V (1978) Advertising and welfare. Bell J Econ 9(1):1–17

Dulleck U, Kerschbamer R (2006) On doctors, mechanics, and computer specialists: the economics of credence goods. J Econ Lit 44(1):5–42

Gifford K, Bernard J (2011) The effect of information on consumers’ willingness to pay for natural and organic chicken. Int J Consum Stud 35:282–289

Glaeser E, Ujhelyi G (2010) Regulating misinformation. J Public Econ 94:247–257

Goss J, Holcomb R, Ward C (2002) Factors influencing consumer concerns related to natural beef in the southern plains. J Food Distrib Res 33:73–84

Hamilton S, Zilberman D (2006) Green markets, eco-certification, and equilibrium fraud. J Environ Econ Manag 52:627–644

Hattori K, Higashida K (2012) Misleading advertising in duopoly. Can J Econ 45(3):1154–1187

Hattori K, Higashida K (2014) Misleading advertising and minimum quality standards. Inf Econ Policy 28:1–14

Kreps D, Scheinkman J (1983) Quantity precommitment and Bertrand competition yield Cournot outcomes. Bell J Econ 14(2):326–337

Martinez S (2010) Varied interests drive growing popularity of local foods. USDA Economic Research Service Report 8(4). http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/121427/2/01LocalFoods.pdf

Mason C (2013) The economics of eco-labeling: theory and empirical implications. Int Rev Environ Resour Econ 6(4):341–372

Motta M (1993) Endogenous quality choice: price vs. quantity competition. J Ind Econ 41:113–131

Oberholtzer L, Greene C, Lopez E (2006) Organic poultry and eggs capture high price premiums and growing share of specialty markets. Report No. LDP-M-150-01, USDA Economic Research Service. http://www.ers.usda.gov/Publications/LDP/2006/12Dec/LDPM15001/ldpm15001.pdf

Pezzino M (2010) Minimum quality standards with more than two firms under Cournot competition. IUP J Manag Econ 8(3):26–40

Ronnen U (1991) Minimum quality standards, fixed costs, and competition. RAND J Econ 22(4):490–504

Scarpa C (1998) Minimum quality standards with more than two firms. Int J Ind Organ 16(5):665–676

Schmidt R (2009) Welfare in differentiated oligopolies with more than two firms. Int J Ind Organ 27:501–507

Shaked A, Sutton J (1982) Relaxing price competition through product differentiation. Rev Econ Stud 49:3–13

Sutton J (1997) Game-theoretic models of market structure. In: Kreps D, Wallis K (eds) Advances in economics and econometrics: theory and applications, vol I. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 66–86

Tietenberg T (1998) Disclosure strategies for pollution control. Environ Resour Econ 11(3–4):587–602

Valletti T (2000) Minimum quality standards under Cournot competition. J Regul Econ 18:235–245

Acknowledgments

We thank Arnab Basu, Amrita Ray Chaudhuri, Ngo Van Long, anonymous referees and a co-editor of this journal for useful comments and suggestions. Financial support for this research from Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the University of Winnipeg’s Board of Regents is gratefully acknowledged. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Equations (15)–(17) and (21)–(23) show that, under both Bertrand and Cournot competition, profit of each firm in the first stage of the game is a function of true product qualities and the misinformation parameter, i.e. \(\pi _i (s_b ,s_n ,s_g ,\beta )\) with \(i=g,n,b\). The FOC for profit maximization with respect to quality chosen by each firm is

Totally differentiating the three FOCs and arranging the equations in matrix form, we obtain

The above system of three equations can be solved simultaneously using Cramer’s rule to obtain the equilibrium value of \(ds_i /d\beta \) as a function of \(\beta \). In particular, the sign of \(ds_i /d\beta \) indicates the comparative static effect of a change in \(\beta \) on the equilibrium value of \(s_i \). Given the complexity of equations (15)–(17) and (21)–(23), we obtain large algebraic expressions for \({\partial F_i }/{\partial \beta }, {\partial F_i }/{\partial s_j }\) and \(\partial F_i /\partial s_i \), which are not reported in the paper. Instead, we report their values in Table 3 for two alternative values of \(\beta \), i.e. \(\beta =1\) (misinformation is absent) and \(\beta =0.9\) (misinformation is significant). Table 3 shows that the magnitude and, in certain cases, the sign of these partial derivatives depend on (i) the nature of market competition, i.e. Bertrand or Cournot, and (ii) the prevailing level of misinformation. Note that the SOC for profit maximization by firm i requires that \({\partial F_i }/{\partial s_i }<0\).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baksi, S., Bose, P. & Xiang, D. Credence Goods, Misleading Labels, and Quality Differentiation. Environ Resource Econ 68, 377–396 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-016-0024-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-016-0024-4