Abstract

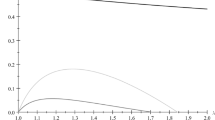

The literature that analyzes the coordination of environmental taxes by governments considers that firms produce a single good at a single plant. However, in practice firms tend to produce several goods at various production plants (multiproduct firms). These firms may organize themselves in a centralized or decentralized fashion for purposes of decision-making: This affects their output and pollution levels. This paper sets out to analyze the coordination of environmental taxes considering multiproduct firms. We find that the organizational structure chosen by the owners of the firms depends on whether or not governments coordinate with one another in setting taxes, and on whether the goods produced are substitutes or complements. Social welfare is greater if a supranational authority sets taxes in all countries. In this case, joint welfare is never lower if the authority is constrained to set the same tax in all countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The European Commission (2011) points out that “to achieve a socially optimal level of environmental taxation, to benefit from the experiences of those Member States that have made intensive use of environmental taxes and to contribute to a level playing field for EU businesses, EU wide and international coordination should be enhanced”.

One example of a decentralized multiproduct firm is the case of General Motors. This firm delegates operational authority to its divisional managers although the products of each division compete in the same market. This independence between the different divisions has been maintained over the time (see Moody’s Industrial Manual 1994). Another example of a divisionalized firm is the French group BSN (see Faure 1990). The divisions of this firm have a significant degree of autonomy (in the implementation of the strategy defined at group level) and the performance of each division is assessed on the basis of its profits or losses.

Markusen and Venables (1988) argue that international markets can be considered as a single market if all arbitrage opportunities are actually utilized. The analysis conducted in this paper refers to countries that belong to a free trade area such as the EU. Firms sell their products freely in the countries belonging to this single market. Moreover, governments decide their environmental policies independently and the EU provides directives that constraint those policies.

Margison (1985) points out that one of the advantages of an M-form structure is that the system of internal controls instituted by top management aims to induce profit maximizing behavior on the part of operational management at divisional level.

Thus, when the goods produced by a centralized multiproduct firm are substitutes (complements) the firm takes on board that one of its plants is competing (cooperating) with the other, which reduces (increases) output at both plants. This does not happen at a decentralized firm.

A supranational authority can set the same tax per unit of pollution emitted on all firms in order to prevent inconsistent treatment of firms with the same production technology. Besides, two identical countries can credibly commit, via legislation that is costly to change, to identical tax rates.

Large corporations are characterized by separation of ownership and control (Fama and Jensen 1983).

We assume that firms can commit themselves to incentive schemes so incentive contracts become common knowledge when the contract is signed. Incentive contracts cost more to change than output decisions, and therefore tend to remain unaltered for a substantial period of time (while output decisions are being changed) and are likely to be observed by rivals. This assumption is crucial to our results, as well as to most literature on incentive contracts. If this assumption is not made, contracts cannot act as commitment devices (see Katz 1991).

The consumer surplus derived from overall demand can be obtained assuming a representative consumer who maximizes \(U(q_{1}, q_{2})-p_{1}q_{1}- p_{2}q_{2}\), where \(q_{i}= q_{iA}+ q_{iB}\) is the amount of the good \(i\) and \(p_{i}\) is its price, \(i = 1, 2\). The function \(U(q_{1}, q_{2})\) is assumed to be quadratic, strictly concave and symmetric in \(q_{1}\) and \(q_{2}: U(q_{1}, q_{2})=a(q_{1}+q_{2})-((q_{1})^{2}+2 bq_{1}q_{2}+(q_{2})^{2})/2, 1>b>-1\). We consider a simplified version of the model used by Vives (1984): We assume that \(b<1\) to assure that the function \(U(q_{1}, q_{2})\) is strictly concave.

The organizational form chosen by firms is a long-run decision and, thus, it is a variable that is harder to change than environmental taxes: The latter can be changed in a shorter period of time, depending on the economic situation of the countries and on the objective function of each government.

When parameter \(g\) is low enough, the environmental tax is negative and the government subsidizes pollutant emissions. Such a subsidy results in firms not abating emissions so it is in fact a subsidy per unit of production. However, “Article 87 of the EC Treaty prohibits any aid granted by a Member State or through State resources in any form whatsoever which distorts or threatens to distort competition by favouring certain firms or the production of certain goods” (http://ec.europa.eu/competition/legislation/treaties/ec/art87_en.html). We assume that \(d=g=\)1 to assure that in equilibrium the environmental tax chosen by the government is always positive. It can be shown, assuming positive environmental taxes, that the results obtained in the paper are robust to changes in these parameters.

In order to simplify the exposition of the results we assume, with no loss of generality, that multiproduct firms adopt the same organizational form to make production and abatement decisions. Thus, abatement and production decisions are made by the same agent.

It can be shown (see “Appendix 8.1”) that this result is the opposite to that obtained when firms do not pollute the environment (or when firms pollute the environment but there are no environmental policies to control pollution).

Given that in equilibrium the two firms set up the same organizational form (both centralize or both decentralize), we compare only the results obtained in these two cases. A comparison with the case in which firms set up different organizational forms is relegated to “Appendix 8.1”.

If \(b=0\), the owners of the firms are indifferent between centralizing and decentralizing decisions and social welfare is the same in both cases.

Note that the rent capture effect and the pollution-shifting effect are not present since there is no strategic interaction between governments when setting taxes.

By assuming uniproduct firms, the literature on the environment shows that the underproduction effect dominates, so environmental taxes are set below marginal environmental damage to avoid an excessive reduction in production by firms.

If \(-1<b<-0.6160\) there are two equilibria: in one of them both firms decentralize decisions and in the other both firms centralize them. However, as \(\pi ^{DD}>\pi ^{CC}\) the first equilibrium Pareto dominates the second one.

It should be noted that the symmetry of the model (identical firms, identical countries and simultaneous decisions) leads to a symmetric result. It is necessary to consider some asymmetry (e.g. that firms have different technologies or that decisions are sequential) to obtain an asymmetric equilibria. Moreover, when firms choose different organizational forms one firm gains a strategic advantage at the expense of the other. Thus, both firms have an incentive to choose the same organizational form.

References

Bárcena-Ruiz JC, Campo ML (2012) Partial cross-ownership and strategic environmental policy. Resour Energy Econ 34:198–210

Bárcena-Ruiz JC, Garzón MB (2003) Strategic environmental standards, wage incomes and the location of polluting firms. Environ Resour Econ 24(2):121–139

Bárcena-Ruiz JC (2006) Environmental taxes and first-mover advantages. Environ Resour Econ 35(1):19–39

Barnett AH (1980) The Pigouvian tax rule under monopoly. Am Econ Rev 70:1037–1041

Barrett S (1994a) Strategic environmental policy and international trade. J Public Econ 54:325–338

Barrett S (1994b) Self-enforcing international environmental agreements. Oxf Econ Pap 46:878–894

Carlsson F (2000) Environmental taxation and strategic commitment in duopoly models. Environ Resour Econ 15(3):243–256

Chandler AD (1969) Strategy and structure: chapters in the history of the American industrial enterprise. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Chandler AD (1990) Scale, scope and organizational capabilities, chapter two in scale and scope. Harvard University Press, New York

Conrad K (1993) Taxes and subsidies for pollution intensive industries as trade policy. J Environ Econ Manag 25(2):121–135

Conrad K (1996a) Optimal environmental policy for oligopolistic industries under intra-industry trade. In: Carraro C, Katsoulacos Y, Xepapadeas A (eds) Environmental policy and market structure. Kluwer, The Netherlands

Conrad K (1996b) Choosing emission taxes under international price competition. In: Carraro C, Katsoulacos Y, Xepapadeas A (eds) Environmental policy and market structure. Kluwer, The Netherlands

Duval TY, Hamilton SF (2002) Strategic environmental policy and international trade in asymmetric oligopoly markets. Int Tax Public Financ 9(3):259–271

Eerola E (2004) Environmental tax competition in the presence of multinational firms. Int Tax Public Financ 11(3):283–298

European Commission (2011) Growth-friendly tax policies in member states and better tax coordination in the EU. Annex IV to the Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of Regions

Fama EF, Jensen MC (1983) Separation of ownership and control. J Law Econ 26:301–325

Faure G (1990) Structure, organization et efficacité de l’entreprise. Dunod, Paris

Goolsbee A (2004) The impact of the corporate income tax: evidence from stat organizational form data. J Public Econ 88:2283–2299

Hoel M (1997) Coordination of environmental policy for transboundary environmental problems? J Public Econ 66:199–224

Katsoulacos Y, Xepapadeas A (1995) Environmental policy under oligopoly with endogenous market structure. Scand J Econ 97(3):411–420

Katz ML (1991) Game-playing agents: unobservable contracts as precommitments. Rand J Econ 22:307–328

Kennedy P (1994) Equilibrium pollution taxes in open economies with imperfect competition. J Environ Econ Manag 27:49–63

Luna L, Murray M (2010) The effects of state tax structure on business organizational form. Natl Tax J 63:995–1022

Margison P (1985) The multidivisional firm and control over the work process. Int J Ind Organ 3:37–56

Markusen JR (1997) Costly pollution abatement, competitiveness and plant location decisions. Resour Energy Econ 19:299–320

Markusen JR, Morey ER, Olewiler N (1995) Competition in regional environmental policies when plant locations are endogenous. J Public Econ 56:55–77

Markusen JR, Venables A (1988) Trade policy with increasing returns and imperfect competition: contradictory results from competing assumptions. J Int Econ 24:299–316

McGinti M (2007) International environmental agreements among asymmetric nations. Oxf Econ Pap 59:45–62

Moody’s Industrial Manual (1994). Moody’s Investors Service. New York

Rauscher M (1995) Environmental regulation and the location of polluting industries. Int Tax Public Financ 2(2):229–244

Simpson RD (1995) Optimal pollution taxation in a Cournot duopoly. Environ Resour Econ 6(4):359–369

Ulph A (1996) Environmental policy and international trade when governments and producers act strategically. J Environ Econ Manag 30:256–281

van der Ploeg F, de Zeeuw AJ (1992) International aspects of pollution control. Environ Resour Econ 2:117–139

Vives X (1984) Duopoly information equilibrium: Cournot and Bertrand. J Econ Theory 34:71–94

Williamson OE (1975) Markets and hierarchies. Analysis and antitrust implications. The Free Press, New York

Williamson OE (1985) The economic institutions of capitalism. The Free Press, New York

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Financial support from Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología and FEDER (ECO2009-07939 and ECO2012-32299) and Departamento de Educación, Universidades e Investigación del Gobierno Vasco (IT-223-07) is gratefully acknowledged. We wish to thank the Associated Editor, Hassan Benchekroun, and two anonymous referees for helpful comments.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 No Coordination of Environmental Policies

When firms adopt different organizational structures, in the second stage each government unilaterally sets the tax that maximizes domestic welfare, taking into account the output and the abatement levels chosen by firms, given by expression (11). Solving these problems we obtain that taxes are strategic complements.

Lemma 8.1

When governments do not coordinate their environmental policies and firms take different organizational forms, in equilibrium:

where \(H=(a-c)/(4089+7423b+4899b^{2}+1444b^{3}+192b^{4}+9b^{5})\).

By comparing Lemmas 1, 2 and 8.1 we obtain that, in equilibrium:

-

i)

If \(b>0:\, ED^{DC}>ED^{DD} >ED^{CC}>ED^{CD}\), \(T^{DC}>T^{DD}>T^{CC}>T^{CD}, CS^{DD}>CS^{CD}=CS^{DC}>CS^{CC}\), \(PS^{CC}>PS^{DC}>PS^{CD}>PS^{DD}, W^{DC}>W^{DD}>W^{CC}>W^{CD}\) and \(2W^{DD}>W^{CD}+W^{DC}>2W^{CC}\).

-

ii)

If \(b<0:\, ED^{CD}>ED^{CC} >ED^{DD}>ED^{DC}\), \(T^{CD}>T^{CC}>T^{DD}>T^{DC}, CS^{CC}>CS^{CD}=CS^{DC}>CS^{DD}\), \(W^{CD}>W^{CC}>W^{DD}>W^{DC}\) and \(2W^{CC}>W^{CD}+W^{DC}>2W^{DD}\) and \(PS^{DD}>max\{PS^{CD}, PS^{DC}\}> PS^{CC}\), where \(PS^{DC}>PS^{CD}\) if and only if \(-1<b<-0.5753\).

1.1.1 Firms Do Not Pollute

In this case governments do not set environmental taxes and firms do not have to abate emissions. It can be shown that in this case:

Finally, \(\pi ^{CC}>\pi ^{DD}\) if \(b>0, \pi ^{CC}<\pi ^{DD}\) if \(b<0\) and \(\pi ^{CC}=\pi ^{DD}\) if \(b=0\).

1.2 Partial Environmental Coordination

1.2.1 Both Firms Decentralize Decisions

In the fourth stage, given the taxes chosen by the supranational authority, the manager of plant ik chooses \(q_{ik}\) and \(a_{ik}\) that maximize the plant’s profit given by (1). Each multiproduct firm solves the same problem as in Sect. 3.1; thus, the result obtained in this stage is given by expression (3). In the third stage the supranational authority chooses \(t_{k}\) and \(t_l\) that maximize joint welfare. Solving, we obtain reaction functions in environmental taxes:

The above expression shows that environmental taxes are strategic complements. Then, the following result is obtained.

Lemma 8.2

When governments partially coordinate their environmental policies and both multiproduct firms decentralize decisions, in equilibrium:

1.2.2 Both Firms Centralize Decisions

In the fourth stage, for given taxes each multiproduct firm delegates production decisions to the head of the firm. The head of firm \(k\) chooses \(q_{1k}, q_{2k}, a_{1k}\) and \(a_{2k}\) that maximize the joint profit of both plants. The result of this stage is given by expression (7). In the third stage the supranational authority sets the environmental taxes \(t_{k}\) and \(t_{l}\) that maximize joint welfare. Solving, we obtain reaction functions in environmental taxes:

The above expression shows that environmental taxes are strategic complements. Then, the following result is obtained.

Lemma 8.3

When governments partially coordinate their environmental policies and both multiproduct firms centralize decisions, in equilibrium:

1.2.3 Firms Set Up Different Organizational Forms

In this case we consider that firm \(k\) centralizes production decisions while firm \(l\) decentralizes them (\(k\ne l, k, l=A, B\)). In the fourth stage each firm solves the same problem as in Sect. 3.3; thus, the result obtained in this stage is given by expression (5). In the third stage the supranational authority chooses the taxes \(t_{k}\) and \(t_{l}\) that maximize joint welfare. Solving, we obtain that taxes are strategic complements.

Lemma 8.4

When governments partially coordinate their environmental policies and firms set up different organizational forms, in equilibrium:

where \(G=(a-c)/(1197+1752b+848b^{2}+150b^{3}+9b^{4}).\)

The decision of the firms on whether to centralize decisions or not when governments partially coordinate their environmental policies remains to be analyzed. This decision, made at stage two, depends on whether goods are substitutes or complements. By comparing the results obtained in Lemmas 8.2, 8.3 and 8.4 we obtain the following.

Lemma 8.5

When governments partially coordinate their environmental policies, in equilibrium:

-

i)

If \(b>0: q^{DC}>q^{DD}>q^{CC}>q^{CD}\), \(e^{DC}>e^{DD}>e^{CC}>e^{CD}, t^{DC}>t^{DD}>t^{CC}>t^{CD}\), \(ED^{DC}>ED^{DD}>ED^{CC}> ED^{CD}, T^{DC}>T^{DD}>T^{CC}>T^{CD}, CS^{DD}>CS^{CD}=CS^{DC}>CS^{CC}, PS^{CC}>PS^{DC}>PS^{CD}>PS^{DD}, W^{DC}>W^{DD}>W^{CC}>W^{CD}\) and \(2W^{DD}>W^{CD}+W^{DC}>2W^{CC}\).

-

ii)

If \(b<0: q^{CD}>q^{CC}>q^{DD}>q^{DC}, e^{CD}>e^{CC}>e^{DD}>e^{DC}, t^{CD}>t^{CC}>t^{DD}>t^{DC}, ED^{CD}>ED^{CC}>ED^{DD}>ED^{DC}, T^{CD}>T^{CC}>T^{DD}>T^{DC}, CS^{CC}>CS^{CD}=CS^{DC}>CS^{DD}\), and \(PS^{DD}>max\{PS^{CD}, PS^{DC}\}>PS^{CC}\), where \(PS^{DC} >PS^{CD}\) if and only if \(-1<b< -0.6274\); \(W^{CD}> W^{CC}>W^{DD}>W^{DC}\) and \(2W^{CC}>W^{CD}+W^{DC}>2W^{DD}\).

This result is similar to that obtained in the non coordination case. However, under partial coordination the taxes chosen by governments are different from those when there is no coordination since in the first case the supranational authority maximizes the joint social welfare of both countries while in the second case each government maximizes its own social welfare.

1.3 Full Environmental Coordination

1.3.1 Firms Set Up Different Organizational Forms

In the third stage the supranational authority chooses the tax that maximizes joint welfare, taking into account the output and the abatement levels, given by expression (5), where \(t_k =t_l =t\). Solving, we obtain the following.

Lemma 8.6

When governments fully coordinate their environmental policies and firms take different organizational forms, in equilibrium:

-

i)

if \(-0.5169 <b <1\):

$$\begin{aligned} t^{CD}&= t^{DC}= M(18+27b+15b^{2}+2b^{3}),\\ q^{CD}&= 3M(5+5b+b^{2}), \, q^{DC} = 3M(5+10b+6b^{2}+b^{3}),\\ e^{CD}&= (M/2)(12+3b-9b^{2}-2b^{3}), \, e^{DC} = (M/2)(12+33b+21b^{2}+4b^{3}),\\ CS^{CD}&= CS^{DC} =9(M^{2}/2)(1+b)(10+15b+7b^{2}+b^{3})^{2},\\ \pi ^{CD} \!&= \!PS^{CD} \!=\!(M^{2}/2)(1224\!+\!3672b\!+\!4329b^{2}\!+\!2502b^{3}\!+\!729b^{4}\!+\!96b^{5}\!+\!4b^{6}),\\ \pi ^{DC} \!&= \!PS^{DC} \!=\!(M^{2}/2)(1224\!+\!4572b\!+\!7029b^{2}\!+\!5562b^{3}\!+\!2349b^{4}\!+\!492b^{5}\!+\!40b^{6}),\\ ED^{CD}&= M^{2}(12+3b-9b^{2}-2b^{3})^{2},\, ED^{DC} =M^{2}(12+33b+21b^{2}+4b^{3})^{2},\\ T^{CD}&= M^{2}(12+3b-9b^{2}-2b^{3})(18+27b+15b^{2}+2b^{3}),\\ T^{DC}&= M^{2}(12+33b+21b^{2}+4b^{3})(18+27b+15b^{2}+2b^{3}),\\ W^{CD} \!&= \!3(M^{2}/2)(756\!+\!2628b\!+\!3642b^{2}\!+\!2547b^{3}\!+\!1002b^{4}\!+\!255b^{5}\!+\!41b^{6}\!+\!3b^{7}),\\ W^{DC} \!&= \!3(M^{2}/2)(756\!+\!2808b\!+\!4242b^{2}\!+\!3423b^{3}\!+\!1566b^{4}\!+\!399b^{5}\!+\!53b^{6}\!+\!3b^{7}). \end{aligned}$$ -

ii)

If \(-1<b< -0.5169\):

$$\begin{aligned} t^{CD}&= t^{DC}= 2J(79+47b+4b^{2}),\\ q^{CD}&= J(133+88b+9b^{2}), \quad q^{DC} = J(97+105b+35b^{2}+3b^{3}),\\ CS^{CD}&= CS^{DC} =(J^{2}/2)(1+b)(230+193b+44b^{2}+3b^{3})^{2},\\ \pi ^{CD}&= PS^{CD} =(2J^{2})(23930+48523b+36387b^{2}+12098b^{3}+1681b^{4}+81b^{5}),\\ \pi ^{DC}&= PS^{DC} =(4J^{2})(97+105b+35b^{2}+3b^{3})^{2},\\ e^{CD}&= J(54+41b+5b^{2}),\quad e^{DC} =0,\\ ED^{CD}&= 4J^{2}(51+41b+5b)^{2},\quad ED^{DC} =0,\\ T^{CD}&= 4J^{2}(79+47b+4b^{2})(54+41b+5b^{2}), \quad T^{DC} =0,\\ W^{CD}&= (J^{2}/2)(159420+346564b+294353b^{2}+124157b^{3}+28142b^{4}\\&+ 3682b^{5}+273b^{6}+9b^{7}),\\ W^{DC}&= (J^{2}/2)(128172+304640b+288789b^{2}+139309b^{3}+36298b^{4}\\&+ 5038b^{5}+345b^{6}+9b^{7}), \end{aligned}$$

where \(M=(a-c)/(63+132b+99b^{2}+ 29b^{3}+3b^{4})\) and \(J=(a-c)/(521+738b+342b^{2}+56b^{3}+3b^{4})\).

By comparing the results obtained in Lemmas 8.2, 8.3 and 8.6 we obtain the following result.

Lemma 8.7

When governments fully coordinate their environmental policies, in equilibrium:

-

i)

If \(b>0: q^{DC}>q^{DD}>q^{CC}>q^{CD}, e^{DC}>e^{DD}>e^{CC}>e^{CD}, ED^{DC}>ED^{DD}>ED^{CC}>ED^{CD}, t^{DD}>t^{CD}= t^{DC}>t^{CC}, T^{DC}>T^{DD}>T^{CC}>T^{CD}, CS^{DD}>CS^{CD}=CS^{DC}>CS^{CC}, PS^{DC}>PS^{CC}>PS^{DD}>PS^{CD}\) and \(2W^{DD}>max\{2W^{CC}, W^{CD}+W^{DC}\}\), where \(2W^{CC}>W^{CD}+W^{DC}\) if and only if \(1>b>0.3050\).

-

ii)

If \(-0.5169 <b<0: q^{CD}>q^{CC}>q^{DD}>q^{DC}, e^{CD}>e^{CC}>e^{DD}>e^{DC}, ED^{CD}>ED^{CC}>ED^{DD}>ED^{DC}, t^{CC}>t^{CD}=t^{DC}>t^{DD}, T^{CD}>T^{CC}>T^{DD}>T^{DC}, CS^{CC}>CS^{CD}=CS^{DC}> CS^{DD}, PS^{CD}>PS^{DD} >PS^{CC}> PS^{DC}, 2W^{CC}> max\{2W^{DD}, W^{CD}+W^{DC}\}\), where \(2W^{DD}> W^{CD}+W^{DC}\) if and only if \(-0.5169<b<-0.1839\).

-

iii)

If \(-1<b<-0.5169: q^{CD}>q^{CC}>q^{DD}>q^{DC}, e^{CD}>e^{CC}>e^{DD}>e^{DC}=0, ED^{CD}>ED^{CC}> ED^{DD} >ED^{DC}=0, t^{CD}=t^{DC}>t^{CC}>t^{DD}, T^{CD}>T^{CC}>T^{DD}>T^{DC}=0, CS^{CC}>max\{CS^{DD},CS^{CD}=CS^{DC}\}, 2W^{CC}>2W^{DD}>W^{CD}+W^{DC}, max\{PS^{CD}, PS^{DD}\}>PS^{CC} >PS^{DC}\), where \(PS^{DD}>PS^{CD}\) if and only if \(-1<b<-0.6160\) and, \(CS^{CD}=CS^{DC}>CS^{DD}\) if and only if \(-1<b<-0.5561\).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bárcena-Ruiz, J.C., Garzón, M.B. Multiproduct Firms and Environmental Policy Coordination. Environ Resource Econ 59, 407–431 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-013-9736-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-013-9736-x