Summary

Background Tivantinib is a non-ATP competitive inhibitor of c-MET receptor tyrosine kinase that may have additional cytotoxic mechanisms including tubulin inhibition. Prostate cancer demonstrates higher c-MET expression as the disease progresses to more advanced stages and to a castration resistant state. Methods 80 patients (pts) with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic mCRPC were assigned (2:1) to either tivantinib 360 mg PO BID or placebo (P). The primary endpoint was progression free survival (PFS). Results Of the 80 pts. enrolled, 78 (52 tivantinib, 26 P) received treatment and were evaluable. Median follow up is 8.9 months (range: 2.3 to 19.6 months). Patients treated with tivantinib had significantly better PFS vs. those treated with placebo (medians: 5.5 mo vs 3.7 mo, respectively; HR = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.33 to 0.90; p = 0.02). Grade 3 febrile neutropenia was seen in 1 patient on tivantinib while grade 3 and 4 neutropenia was recorded in 1 patient each on tivantinib and placebo. Grade 3 sinus bradycardia was recorded in two men on the tivantinib arm. Conclusions Tivantinib has mild toxicity and improved PFS in men with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic mCRPC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) is the lethal version of this common disease. Prostate cancer reaches this point through the combined events of metastasis and adaptation by the tumor to a low testosterone environment. The overall survival of men with mCRPC has improved over the past few years with the introduction of several different agents with non-overlapping mechanisms of action. [1,2,3,4,5] Despite this progress, further improvement is needed as men with mCRPC still invariably succumb to this disease.

C-MET and prostate cancer

Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and its receptor N-methyl-N′-nitrosoguanidine human osteosarcoma transforming gene (MET) seem to play important roles in the metastatic process [6, 7] and its signaling is abnormal in a variety of malignancies [8]. Serum HGF levels are higher in metastatic prostate cancer than in localized tumors [9] and has been associated with poorer outcomes. [10] Xenograft and in vitro data reveal that MET expression increases following androgen deprivation suggesting an association with the development of castrate resistant disease. [11, 12]

Tivantinib

Tivantinib (ARQ 197; ArQule, Burlington, MA; Daichi-Sankyo, Tokyo, Japan) is an orally available selective small molecule that inhibits MET receptor tyrosine kinase with a novel ATP independent binding (allosteric inhibitor) mechanism, leading to inhibition of cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis in MET-expressing cancer cells. [13] [14, 15] Tivantinib has been found to have additional properties and in some preclinical studies its anti-cancer properties were independent of the c-MET inhibition. [16] Together, these findings supported the hypothesis that tivantinib would have activity against mCRPC. We therefore performed a phase II randomized placebo controlled trial of tivantinib in men with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic mCRPC.

Patients and methods

Eligibility criteria

Eligible men were required to have metastatic histologically confirmed prostate adenocarcinoma, castrate testosterone level (<50 ng/dL), to be asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic (no symptoms attributable to prostate cancer greater than Grade 1), ECOG ≤2, and PSA ≥ 2 ng/ml. Prior treatment with sipuleucel- T and abiraterone acetate were allowed. Prior chemotherapy was not allowed unless used in a perioperative setting and completed >6 months prior to enrollment. Progressive disease at study entry was required and defined as two successive rises in PSA separated at least by one week, appearance of two or more new lesions on bone scan, > 20% objective increase in size of target lesion. This is consistent with Prostate Cancer Working Group 2 guidelines (PCWG2) for trials in advanced prostate cancer. [17] Bone targeting agents such as zoledronic acid or denosumab were permitted provided patients began therapy prior to study entry. Normal organ and bone marrow function were required. Exclusion criteria included radiotherapy within 4 weeks, uncontrolled intercurrent illness, known brain metastasis, history of myocardial infarction or unstable angina within 6 months, history of severely impaired lung function, active liver disease, poorly controlled diabetes, or impairment of gastrointestinal function. Institutional review board approval was obtained for all study procedures at each participating site. Each patient provided written informed consent.

Treatment plan

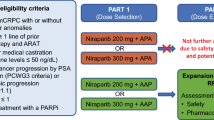

Participants were stratified based on prior treatment with abiraterone acetate and sipuleucel-T and randomly allocated at a ratio of 2:1 to receive tivantinib or placebo in a double-blind fashion. Patients received twice-daily dosing of 360 mg tivantinib by mouth or matched placebo. One cycle was 28 days. At the time of disease progression, the blind could be broken and those assigned to the placebo arm were allowed to cross over to tivantinib. At the time of the trial conduct, abiraterone acetate was approved only in the post-docetaxel setting, and neither enzalutamide nor radium223 were approved. Therefore, placebo in this clinical setting was felt to be appropriate.

Efficacy outcome measures

We used PCWG2 guidelines to define disease progression which included need for palliative radiation or surgery, RECIST 1.1 defined progression, the appearance of ≥2 new bone lesions on Tc99MDP bone scan (with instructions for recognizing flare). Investigator determined clinical deterioration was also considered progression. Rising PSA levels alone while on study drug were not considered disease progression. Toxicity was evaluated using National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (version 4.0).

Pretreatment and follow-up evaluations

At baseline, participants underwent complete history, physical examination and laboratory testing. Baseline imaging was completed ≤4 weeks prior to start of treatment. Patients were evaluated every 4 weeks with repeat examination, safety assessment and standard laboratory testing. Whole body bone imaging, CT of abdomen/pelvis and chest X-ray were performed every 12 weeks or as needed for symptoms suggestive of disease progression.

Statistical considerations

The primary endpoint in this trial was to compare the PFS of tivantinib vs placebo. This was defined as the time from study entry (start of blinded treatment) to the date of documented progression and/or death, censoring alive and progression-free patients at their last follow-up date. In this trial, the proposed sample size of 78 eligible and evaluable patients (26 in the placebo arm, 52 in the tivantinib arm) provided 90% power to detect an improvement from 3 months median PFS with placebo to a median PFS of at least 6 months with the tivantinib treatment, and a Type I error rate of 0.10 was assumed for this one-sided test. This sample size was based on a log-rank test calculation using the R statistical program (gsDesign package, R version 2.11.1).

Since this was a phase II trial with a direct comparison between the treatment arm and a placebo-control arm, we relaxed the Type I error constraint to 0.10. [18] Progression free survival curves based on observed data were constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the hazard ratio of treatment vs. placebo. Adverse events as defined by NCI CTCAE v4.0 were summarized using descriptive statistics, where the maximum grade for each type of toxicity was recorded for each patient, and frequency tables were made to determine toxicity patterns.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between January 2012 and September 2013 eighty men with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic CRPC were enrolled in this multicenter, double-blind phase II trial. Seventy eight men (52 randomly assigned to tivantinib and 26 to matching placebo) started treatment and were included in safety and efficacy analysis. (Fig. 1) Groups were well balanced for most baseline characteristics (Table 1). A higher proportion of men self-identifying as African American and men with lymph node involvement were randomized to placebo. There was no prior treatment with Radium-223, enzalutamide or chemotherapy while nearly a third of patients received prior abiraterone acetate and/or sipuleucel-T.

Efficacy

At the time of primary PFS analysis, 68 patients had progressed and/or died (26/26 on placebo and 42/52 on tivantinib). The median follow-up on event-free patients was 8.9 months (range: 2.3 to 19.6 months). The median PFS for those on the placebo arm was 3.7 months (95% CI: 2.7 to 5.4 months) vs. a median PFS of 5.5 months for those treated with tivantinib (95% CI: 3.2 to 8.0 months). (Fig. 2).

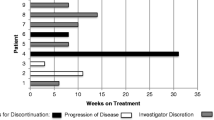

A partial response by RECIST was documented in 1 patient randomized to tivantinib. (Fig. 3) Genomic profiling of this individual with an exceptional response revealed high androgen receptor amplification but no other significant alterations.PSA increases were generally seen on both arms. (Fig. 4).

Crossover from placebo to tivantinib was allowed at the time of progression. 12 of the 26 patients assigned to placebo when they progressed received tivantinib. The median time on tivantinib for this group was 4.3 months with a range of 2 to 10 months. One of the 12 experienced an objective partial response by RECIST. Overall survival was not measured.

Safety

Toxicity is summarized in Table 2. Grade (G) 3 febrile neutropenia was seen in 1 patient on tivantinib while G3 and 4 neutropenia was recorded in 1 patient each on tivantinib and placebo. G3 sinus bradycardia was recorded in two men on the tivantinib arm. Eleven deaths (4 placebo and 7 tivantinib) were recorded during the trial and were all determined to be unrelated to therapy.

Discussion

Treatment with tivantinib was associated with minimal toxicity and a significantly longer PFS when compared to placebo in men with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic mCRPC. In comparing the PFS distributions between treatment arms, the p-value for the log-rank test was p = 0.02. Furthermore, this p-value reflects a two-sided alternative hypothesis, which is more stringent than what was designed in this trial. Tivantinib’s favorable side effect profile has been demonstrated in various clinical trial settings, but these studies failed to achieve their respective primary endpoints. [19,20,21,22,23] This broad lack of efficacy is seen despite an underlying biologic rationale that is similar to the current trial. Several factors should be considered when interpreting the results of the present trial. First, the strengths of our report include the randomized design, the use of PCWG2 guidelines to determine progression and the control arm performed as expected. However, this study’s small size makes it more sensitive to biases that are potentially unaccounted for. More troublesome is the uncertainty of both the underlying mechanism of action of tivantinib and the value of PFS as an important endpoint in mCRPC trials. During the conduct of this trial, preclinical studies reported tivantinib’s activity is not via the inhibition of c-MET/HGF signaling. [16, 24] [25, 26] Rather, the in vitro activity is more consistent with a cytotoxic agent. Targeting MET therefore remains unproven as a strategy that produces clinical benefit in men with mCRPC. [27]

The inability to rely on intermediate endpoints to predict overall survival in mCRPC is problematic. [2, 28,29,30] This must be considered when we interpret the significant improvement in PFS seen in this study. The experience with cabozantinib’s development in mCRPC is perhaps most instructive. [31] Cabozantinib, a potent inhibitor of MET and VEGFR2, failed to improve overall survival (OS) when compared with prednisone in heavily treated men with mCRPC. These negative phase III results were accompanied by significant improvements in bone scan response, radiographic PFS, circulating tumor cell conversions, time to first symptomatic skeletal event and favorable bone biomarker changes. One potential explanation for the lack of OS benefit is the high number of dose reductions and discontinuations for toxicity. The phase II experience was associated with unprecedented tumor regression in the majority with soft tissue disease, normalization of bone scans in 12% and improvement in bone pain in 67%. [32] This apparent paradox seems most acute in advanced prostate cancer trials but it has been seen in other tumor types and caution has been advised when making conclusions with PFS data. [33]

Conclusion

Tivantinib has mild toxicity and significantly improved PFS compared to placebo in men with asymptomatic/minimally symptomatic mCRPC. The magnitude of benefit does not support further evaluation as a single agent. Optimal further development of tivantinib in mCRPC would ideally include a better understanding of the drug’s underlying mechanism of action. This would better inform combination studies with other therapies in mCRPC.

References

Fizazi K, Scher HI, Molina A, Logothetis CJ, Chi KN, Jones RJ, Staffurth JN, North S, Vogelzang NJ, Saad F, Mainwaring P, Harland S, Goodman OB Jr, Sternberg CN, Li JH, Kheoh T, Haqq CM, de Bono JS, COU-AA-301 Investigators (2012) Abiraterone acetate for treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: final overall survival analysis of the COU-AA-301 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 13(10):983–992

Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, Berger ER, Small EJ, Penson DF, Redfern CH, Ferrari AC, Dreicer R, Sims RB, Xu Y, Frohlich MW, Schellhammer PF, IMPACT Study Investigators (2010) Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 363(5):411–422

Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, Taplin ME, Sternberg CN, Miller K, de Wit R, Mulders P, Chi KN, Shore ND, Armstrong AJ, Flaig TW, Fléchon A, Mainwaring P, Fleming M, Hainsworth JD, Hirmand M, Selby B, Seely L, de Bono JS, AFFIRM Investigators (2012) Increased survival with Enzalutamide in prostate Cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 367:1187–1197

de Bono, J.S., et al., Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 376(9747): p. 1147–54

Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, Helle SI, O'Sullivan JM, Fosså SD, Chodacki A, Wiechno P, Logue J, Seke M, Widmark A, Johannessen DC, Hoskin P, Bottomley D, James ND, Solberg A, Syndikus I, Kliment J, Wedel S, Boehmer S, Dall'Oglio M, Franzén L, Coleman R, Vogelzang NJ, O'Bryan-Tear CG, Staudacher K, Garcia-Vargas J, Shan M, Bruland ØS, Sartor O, ALSYMPCA Investigators (2013) Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 369(3):213–223

Lesko E, Majka M (2008) The biological role of HGF-MET axis in tumor growth and development of metastasis. Front Biosci 13:1271–1280

Matsumoto K, Nakamura T (2006) Hepatocyte growth factor and the met system as a mediator of tumor-stromal interactions. Int J Cancer 119(3):477–483

Liu, X., R.C. Newton, and P.A. Scherle, Developing c-MET pathway inhibitors for cancer therapy: progress and challenges. Trends Mol Med. 16(1): p. 37–45

Naughton M et al (2001) Scatter factor-hepatocyte growth factor elevation in the serum of patients with prostate cancer. J Urol 165(4):1325–1328

Humphrey PA, Halabi S, Picus J, Sanford B, Vogelzang NJ, Small EJ, Kantoff PW (2006) Prognostic significance of plasma scatter factor/hepatocyte growth factor levels in patients with metastatic hormone- refractory prostate cancer: results from cancer and leukemia group B 150005/9480. Clin Genitourin Cancer 4(4):269–274

Verras M, Lee J, Xue H, Li TH, Wang Y, Sun Z (2007) The androgen receptor negatively regulates the expression of c-met: implications for a novel mechanism of prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res 67(3):967–975

Singh AP, Bafna S, Chaudhary K, Venkatraman G, Smith L, Eudy JD, Johansson SL, Lin MF, Batra SK (2008) Genome-wide expression profiling reveals transcriptomic variation and perturbed gene networks in androgen-dependent and androgen-independent prostate cancer cells. Cancer Lett 259(1):28–38

Yap TA, Olmos D, Brunetto AT, Tunariu N, Barriuso J, Riisnaes R, Pope L, Clark J, Futreal A, Germuska M, Collins D, deSouza NM, Leach MO, Savage RE, Waghorne C, Chai F, Garmey E, Schwartz B, Kaye SB, de Bono JS (2011) Phase I trial of a selective c-MET inhibitor ARQ 197 incorporating proof of mechanism pharmacodynamic studies. J Clin Oncol 29(10):1271–1279

Eathiraj S, Palma R, Volckova E, Hirschi M, France DS, Ashwell MA, Chan TCK (2011) Discovery of a novel mode of protein kinase inhibition characterized by the mechanism of inhibition of human mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor (c-met) protein autophosphorylation by ARQ 197. J Biol Chem 286(23):20666–20676

Munshi N, Jeay S, Li Y, Chen CR, France DS, Ashwell MA, Hill J, Moussa MM, Leggett DS, Li CJ (2010) ARQ 197, a novel and selective inhibitor of the human c-met receptor tyrosine kinase with antitumor activity. Mol Cancer Ther 9(6):1544–1553

Basilico C, Pennacchietti S, Vigna E, Chiriaco C, Arena S, Bardelli A, Valdembri D, Serini G, Michieli P (2013) Tivantinib (ARQ197) displays cytotoxic activity that is independent of its ability to bind MET. Clin Cancer Res 19(9):2381–2392

Scher HI, Halabi S, Tannock I, Morris M, Sternberg CN, Carducci MA, Eisenberger MA, Higano C, Bubley GJ, Dreicer R, Petrylak D, Kantoff P, Basch E, Kelly WK, Figg WD, Small EJ, Beer TM, Wilding G, Martin A, Hussain M, Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group (2008) Design and end points of clinical trials for patients with progressive prostate cancer and castrate levels of testosterone: recommendations of the prostate Cancer clinical trials working group. J Clin Oncol 26(7):1148–1159

Friedman LF, DeMets CD (1998) DL, Fundamentals of Clinical trials. Springer-Verlag, New York

Kang YK, Muro K, Ryu MH, Yasui H, Nishina T, Ryoo BY, Kamiya Y, Akinaga S, Boku N (2014) A phase II trial of a selective c-met inhibitor tivantinib (ARQ 197) monotherapy as a second- or third-line therapy in the patients with metastatic gastric cancer. Investig New Drugs 32(2):355–361

Pant S, Patel M, Kurkjian C, Hemphill B, Flores M, Thompson D, Bendell J (2017) A phase II study of the c-met inhibitor Tivantinib in combination with FOLFOX for the treatment of patients with previously untreated metastatic adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus, Gastroesophageal junction, or stomach. Cancer Investig 35(7):463–472

Scagliotti G, von Pawel J, Novello S, Ramlau R, Favaretto A, Barlesi F, Akerley W, Orlov S, Santoro A, Spigel D, Hirsh V, Shepherd FA, Sequist LV, Sandler A, Ross JS, Wang Q, von Roemeling R, Shuster D, Schwartz B (2015) Phase III multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of Tivantinib (ARQ 197) plus Erlotinib versus Erlotinib alone in previously treated patients with locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous non-small-cell lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 33(24):2667–2674

Tolaney SM, Tan S, Guo H, Barry W, van Allen E, Wagle N, Brock J, Larrabee K, Paweletz C, Ivanova E, Janne P, Overmoyer B, Wright JJ, Shapiro GI, Winer EP, Krop IE (2015) Phase II study of tivantinib (ARQ 197) in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Investig New Drugs 33(5):1108–1114

Rimassa L et al (2017) Second-line tivantinib (ARQ 197) vs placebo in patients (Pts) with MET-high hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): results of the METIV-HCC phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 35

Xiang Q, Zhen Z, Deng DYB, Wang J, Chen Y, Li J, Zhang Y, Wang F, Chen N, Chen H, Chen Y (2015) Tivantinib induces G2/M arrest and apoptosis by disrupting tubulin polymerization in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 34:118

Reuther C, Heinzle V, Spampatti M, Vlotides G, de Toni E, Spöttl G, Maurer J, Nölting S, Göke B, Auernhammer CJ (2016) Cabozantinib and Tivantinib, but not INC280, induce Antiproliferative and Antimigratory effects in human neuroendocrine tumor cells in vitro: evidence for 'Off-Target' effects not mediated by c-met inhibition. Neuroendocrinology 103(3–4):383–401

Michieli P, Di Nicolantonio F (2013) Targeted therapies: Tivantinib--a cytotoxic drug in MET inhibitor's clothes? Nat Rev Clin Oncol 10(7):372–374

Ryan CJ, Rosenthal M, Ng S, Alumkal J, Picus J, Gravis G, Fizazi K, Forget F, Machiels JP, Srinivas S, Zhu M, Tang R, Oliner KS, Jiang Y, Loh E, Dubey S, Gerritsen WR (2013) Targeted MET inhibition in castration-resistant prostate cancer: a randomized phase II study and biomarker analysis with rilotumumab plus mitoxantrone and prednisone. Clin Cancer Res 19(1):215–224

Michaelson MD, Oudard S, Ou YC, Sengeløv L, Saad F, Houede N, Ostler P, Stenzl A, Daugaard G, Jones R, Laestadius F, Ullèn A, Bahl A, Castellano D, Gschwend J, Maurina T, Chow Maneval E, Wang SL, Lechuga MJ, Paolini J, Chen I (2014) Randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of sunitinib plus prednisone versus prednisone alone in progressive, metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 32(2):76–82

Kelly WK, Halabi S, Carducci M, George D, Mahoney JF, Stadler WM, Morris M, Kantoff P, Monk JP, Kaplan E, Vogelzang NJ, Small EJ (2012) Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial comparing docetaxel and prednisone with or without bevacizumab in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: CALGB 90401. J Clin Oncol 30(13):1534–1540

Gignac GA, Morris MJ, Heller G, Schwartz LH, Scher HI (2008) Assessing outcomes in prostate cancer clinical trials: a twenty-first century tower of babel. Cancer 113(5):966–974

Smith M, de Bono J, Sternberg C, le Moulec S, Oudard S, de Giorgi U, Krainer M, Bergman A, Hoelzer W, de Wit R, Bögemann M, Saad F, Cruciani G, Thiery-Vuillemin A, Feyerabend S, Miller K, Houédé N, Hussain S, Lam E, Polikoff J, Stenzl A, Mainwaring P, Ramies D, Hessel C, Weitzman A, Fizazi K (2016) Phase III study of Cabozantinib in previously treated metastatic castration-resistant prostate Cancer: COMET-1. J Clin Oncol 34(25):3005–3013

Smith DC, Smith MR, Sweeney C, Elfiky AA, Logothetis C, Corn PG, Vogelzang NJ, Small EJ, Harzstark AL, Gordon MS, Vaishampayan UN, Haas NB, Spira AI, Lara PN Jr, Lin CC, Srinivas S, Sella A, Schöffski P, Scheffold C, Weitzman AL, Hussain M (2013) Cabozantinib in patients with advanced prostate cancer: results of a phase II randomized discontinuation trial. J Clin Oncol 31(4):412–419

Fleming TR, Rothmann MD, Lu HL (2009) Issues in using progression-free survival when evaluating oncology products. J Clin Oncol 27(17):2874–2880

Funding

This project has been funded by the National Cancer Institute under Contract No. HHSN261201100070C.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interests

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interests to report.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This trial was approved by each participating institution’s Institutional Review Board.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Monk, P., Liu, G., Stadler, W.M. et al. Phase II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of tivantinib in men with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). Invest New Drugs 36, 919–926 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10637-018-0630-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10637-018-0630-9