Abstract

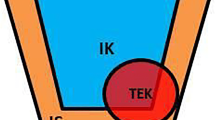

For 5 years, we have taught an interdisciplinary experiential environmental philosophy—field philosophy—course in Isle Royale National Park. We crafted this class with a pedagogy and curriculum guided by the ethic of care (Goralnik et al. in J Experiential Education 35(3):412–428, 2012) and a Leopold-derived community-focused environmental ethic (Goralnik and Nelson in J Environ Educ 42(3):181–192, 2011) to understand whether and how wilderness experience might impact the widening of students’ moral communities. But we found that student pre-course writing already revealed a preference for nonanthropocentric and nonutilitarian ethics, albeit with a naïve understanding that enabled contradictions and confusion about how these perspectives might align with action. By the end of the course, though, we recognized a recurrent pattern of learning and moral development that provides insight into the development of morally inclusive environmental ethics. Rather than shift from a utilitarian or anthropocentric ethic to a more biocentric or ecocentric ethic, students instead demonstrated a metaphysical shift from a worldview dominated by dualistic thinking to a more complex awareness of motivations, actions, issues, and natural systems. The consistent occurrence of this preethical growth, observed in student writing and resulting from environmental humanities field learning, demonstrates a possible path to ecologically informed holistic environmental ethics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This is a somewhat new phenomenon practiced by a few philosophers (Brady et al. 2004; Moore 2004) and on several humanistic field courses (Algona and Simon 2010; Johnson and Frederickson 2000, “Outdoor Philosophy”). The terms experiential environmental philosophy and field philosophy are not used in this literature, though other programs do refer to their work as field philosophy, including University of North Texas’s Sub-Antarctic Biocultural Conservation Program (UNT); the way we use these terms here is specific to the model described in our research.

Students apply for the course with a one-page letter about their experience and interest. Interviews follow, and students are invited to participate after the interview process. Some years, there is so much interest we have interviewed half the applicants and then brought half the interviewed students on the course. Other years, no interviews were necessary. A waitlist is created for students not chosen (because they are underclassmen, do not seem enthusiastic about the content or collaborative environment, or are not in good standing on campus).

More work is needed to further explore the distinctions between classroom and field learning. It is not clear whether these kinds of learning and personal shifts can be facilitated as effectively in the classroom environment or whether they are more easily or permanently fostered in the field.

For the full list and descriptions of the wilderness arguments discussed in this paper, see Nelson (1998).

References

Algona, P.S., and G.L. Simon. 2010. The role of field study in humanistic and interdisciplinary environmental education. Journal of Experiential Education 32(3):191–206.

Brady, Emily, Alan Holland, and Kate Rawles. 2004. Walking the talk: Philosophy of conservation on the Island of Rum. Worldviews 8(2–3):280–297.

Callicott, J.Baird. 1986. The metaphysical implications of ecology. Environmental Ethics 8:301–316.

Callicott, J.Baird. 1990. The case against moral pluralism. Environmental Ethics 12:99–124.

Charmaz, Kathy. 2006. Grounded Theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage Publications.

Elder, John (ed.). 1998. Stories in the land: A place-based environmental education anthology. Barrington, MA: The Orion Society.

Freese, Curtis H., and David L. Trauger. 2000. Wildline markets and biodiversity conservation in North America. Wildlife Society Bulletin 28(1):42–51.

Geertz, Clifford. 1973. Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture. The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays, 3–30. New York: Basic Books.

Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm L. Strauss. 1967. The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Co.

Goralnik, Lissy, and Michael P. Nelson. 2011. Framing a philosophy of environmental action: Aldo Leopold, John Muir, and the importance of community. The Journal of Environmental Education 42(3):181–192.

Goralnik, L., K. Millenbah, M.P. Nelson, and L. Thorp. 2012. An environmental pedagogy of care: Emotion, relationships, and experience in higher education. The Journal of Experiential Education 35(3):412–428.

Grace, Marcus M., and Mary Ratcliffe. 2002. The science and values that young draw upon to make decisions about biological conservation issues. International Journal of Science Education 24(11):1157–1169. doi:10.1080/09500690210134848.

Guba, E.G., and Y.S. Lincoln. 1994. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In Handbook of qualitative research, ed. N.K. Denzin, and Y.S. Lincoln, 105–117. London: Sage.

Hungerford, Harold R., and Trudie L. Volk. 1990. Changing learner behavior. Journal of Environmental Education 21(3):8–21.

Johnson, B.L., and L.M. Frederickson. 2000. ‘What’s in a good life?’ Searching for ethical wisdom in the wilderness. The Journal of Experiential Education 23(1):43–50.

Jones, Peter C., J.Quentin Merritt, and Clare Palmer. 1999. Critical thinking and interdisciplinarity in environmental higher education: The case for epistemological and values awareness. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 2:349–357.

Kellstedt, M., S. Zahran, and A. Vedlitz. 2008. Personal efficacy, the information environment, and attitudes toward global warming and climate change in the United States. Risk Analysis 28(1):113–126.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. 2013. Braiding Sweetgrass. Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions.

Knapp, Clifford E. 2005. The ‘I-thou’ relationship, place-based education, and Aldo Leopold. The Journal of Experiential Education 27(3):277–285.

Kollmuss, Anja, and Julian Agyeman. 2002. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental Education Research 8(3):239–260.

Knapp, Doug and Poff, Raymond. 2001. A qualitative analysis of the immediate and short-term impact of an environmetnal interpretive program. Environmental Education Research 7(1):55–65.

Kulpa, Jack. 2002. The wind in the wire. True North, 141–147. Lanham, MD: Taylor Trade Publishing.

Leopold, Aldo. 1949. A Sand County almanac and sketches here and there. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lincoln, Y., and E. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications. Inc.

Loomis, J.B. 2000. Can environmental economic valuation techniques aid ecological economics and wildlife conservation? Wildlife Society Bulletin 28(1):52–60.

Louv, Richard. 2009. A walk in the woods. Orion. Retrieved March 24, 2009. www.orionmagazine.org.

Marcinkowski, Tom. 1998. Predictors of environmental behavior: A review of three dissertation studies. In Essential readings in environmental education, ed. H.R. Hungerford, W.J. Bluhm, T.L. Volk, and J.M. Ramsey, 227–236. Champaign, IL: Stipes.

Mathews, Freya. 1991. The ecological self. London: Routledge.

Maykut, P., and R. Morehouse. 1994. Beginning qualitative research: A philosophic and practical guide. London: The Falmer Press.

Moore, Kathleen Dean. 2004. Pine Island paradox. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions.

Moore, Kathleen Dean, and Michael P. Nelson (eds.). 2010. Moral ground. San Antonio, TX: Trinity University Press.

Mortari, L. 2004. Educating to care. The Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 9(1):109–122.

Nelson, M.P. 1998. An amalgamation of wilderness preservation arguments. In The great new wilderness debate, ed. J.B. Callicott, and M.P. Nelson, 154–200. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

Nelson, Michael P. 1996. Holists, fascists, and paper tigers…Oh my! Ethics and the Environment 1(2):102–117.

Peterson, Rolf O. 2008. Letting nature run wild in the National Parks. In: Michael P. Nelson and J. Baird Callicott (Eds.). The Wilderness Debate Rages On pp. (645–663). Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

Plumwood, Val. 1991. Nature, self, and gender: Feminism, environmental philosophy, and the critique of rationalism. Hypatia 6(1):3–27.

Preston, C.J. 2003. Grounding knowledge: Environmental philosophy, epistemology, and place. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

Proudman, B. 1992. Experiential education as emotionally-engaged learning. The Journal of Experiential Education 15(2):19–23.

Ramsey, C., and R. Rickson. 1977. Environmental knowledge and attitudes. Journal of Environmental Education 13(1): 24–29.

Russell, Constance L. & Bell, Anne C. 1996. A politicized ethic of care: Environmental education from an ecofeminist perspective. In: K. Warren (Ed.). Women’s Voices in Experiential Education. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. pp. 172–181.

Smith-Sebasto, N.J. 1995. The effects of an environmental studies course on selected variables related to environmentally responsible behavior. The Journal of Environmental Education 26(4): 30–34.

Sobel, David. 2004. Place-based education: Connecting classrooms and communities. Great Barrington, MA: The Orion Society.

Strauss, Anselm and Corbin, Juliet M. 1990. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded Theory procedures and techniques. London: Sage Publications.

Vucetich, John, and Michael P. Nelson. 2013. The infirm ethical foundations of conservation. In Ignoring nature no more: The case for compassionate conservation, ed. Marc Bekoff, 9–25. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Warren, Karen J. 2000. Ecofeminist philosophy. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Wolcott, Harry F. 1994. On seeking—and rejecting—validity in qualitative research. Transforming Qualitative Data: Description, Analysis, and Interpretation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications: 337–371.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goralnik, L., Nelson, M.P. Field philosophy: dualism to complexity through the borderland. Dialect Anthropol 38, 447–463 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10624-014-9346-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10624-014-9346-1