Abstract

Background and Aims

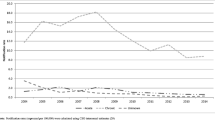

The Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study (CHeCS) is a longitudinal observational study of risks and benefits of treatments and care in patients with chronic hepatitis B (HBV) and C (HCV) infection from four US health systems. We hypothesized that comparative effectiveness methods—including a centralized data management system and an adaptive approach for cohort selection—would improve cohort selection while controlling data quality and reducing the cost.

Methods

Cohort selection and data collection were performed primarily via the electronic health record (EHR); cases were confirmed via chart abstraction. Two parallel sources fed data to a centralized data management system: direct EHR data collection with common data elements, and chart abstraction via electronic data capture. An adaptive Classification and Regression Tree (CART) identified a set of electronic variables to improve case ascertainment accuracy.

Results

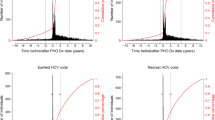

Over 16 million patient records were collected on 23 case report forms in 2006–2008. The vast majority of data (99.2 %) were collected electronically from EHR; only 0.8 % was collected via chart abstraction. Initial electronic criteria identified 12,144 chronic hepatitis patients; 10,098 were confirmed via chart abstraction with positive predictive values (PPV) 79 and 83 % for HBV and HCV, respectively. CART-optimized models significantly increased PPV to 88 for HBV and 95 % for HCV.

Conclusions

CHeCS is a comparative effectiveness research project that leverages electronic centralized data collection and adaptive cohort identification approaches to enhance study efficiency. The adaptive CART model significantly improved the positive predictive value of cohort identification methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- CHeCS:

-

Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B virus

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C virus

- EHR:

-

Electronic health record

- VDW:

-

Virtual Database Warehouse

- DCC:

-

Data coordinating center

- PPV:

-

Positive predictive value

- CART:

-

Classification and Regression Trees

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- AUROC:

-

Area under the ROC curve

- TN:

-

Terminal node

References

Dreyer NA, Schneeweiss S, McNeil BJ, et al. GRACE principles: recognizing high-quality observational studies of comparative effectiveness. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16:467–471.

Alford L, AppSc B. On differences between explanatory and pragmatic clinical trials. N Z J Physiother. 2006;35:12–16.

Tunis SR, Benner J, McClellan M. Comparative effectiveness research: policy context, methods development and research infrastructure. Stat Med. 2010;29:1963–1976.

Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J. The elements of statistical learning: data mining inference and prediction. New York: Springer; 2009.

Johnson ML, Chitnis AS. Comparative effectiveness research: guidelines for good practices are just the beginning. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11:51–57.

Iglehart JK. Prioritizing comparative-effectiveness research–IOM recommendations. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:325–328.

Mushlin AI, Ghomrawi H. Health care reform and the need for comparative-effectiveness research. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:e6.

Rongey C, Yee HF Jr. From the bedside to the community: comparative effectiveness, health services, and implementation research. Hepatology. 2011;53:673–677.

Moorman AC, Gordon SC, Rupp LB, et al. Baseline characteristics and mortality among people in care for chronic viral hepatitis: the chronic hepatitis cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:40–50.

Newton KM, Larson EB. Learning health care systems: leading through research: the 18th annual HMO research network conference, April 29–May 2, 2012, Seattle, Washington, Clin Med Res. 2012;10:140–142.

HMO Resarch Network. Figure: VDW Data Structure. Available via http://www.hmoresearchnetwork.org/asset/d53eea05-a8b6-4ea1-b4d2-6fff5e133deH/HMORN_VDW_Data_Structures.jpg. Accessed 3 July 2014.

Spradling PR, Rupp L, Moorman AC, et al. Hepatitis B and C virus infection among 1.2 million persons with access to care: factors associated with testing and infection prevalence. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1047–1055.

SAS Institute. SAS/STAT 9.2 user guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institution; 2010.

CART 6.0 user’s guide salford systems [computer program]. 2010.

Breiman L, Friedman J, Stone Charles J. Classification and Regression Trees. 1st ed. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1984.

Moore CL, Lu M, Cheema F, et al. Prediction of failure in vancomycin-treated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection: a clinically useful risk stratification tool. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:4581–4588.

Zeger S, Liang K. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–130.

Liang K, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;72:13–22.

Umscheid CA. Maximizing the clinical utility of comparative effectiveness research. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88:876–879.

Gordon SC, Lamerato LE, Rupp LB, et al. Antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis B virus infection and development of hepatocellular carcinoma in a US population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:885–893.

Holmberg SD, Spradling PR, Moorman AC, et al. Hepatitis C in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1859–1861.

Acknowledgments

CHeCS is funded by the CDC Foundation, which currently receives grants from AbbVie, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Vertex Pharmaceuticals. Past funders include Genentech, A Member of the Roche Group. Current and past partial funders include Gilead Sciences and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Granting corporations do not have access to CHeCS data and do not contribute to data analysis or writing of manuscripts.

Conflict of interest

Stuart C. Gordon receives grant/research support from AbbVie Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Intercept Pharmaceuticals, Merck, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals. He is also a consultant/advisor for Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CVS Caremark, Gilead Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Novartis, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals and is on the Data Monitoring Board for Tibotec/Janssen Pharmaceuticals. The other authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

For the Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study (CHeCS) Investigators.

A list of the CHeCS Investigators appears in Appendix 1.

Appendices

Appendix 1: CHeCS Investigators and Sites

Division of Viral Hepatitis, National Centers for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention (NCHHSTP), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Georgia:

Scott D. Holmberg, Eyasu H. Teshale, Philip R. Spradling, Anne C. Moorman, Jim Xing, and Cindy Tong.

Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, Michigan:

Stuart C. Gordon, David R. Nerenz, Mei Lu, Lois Lamerato, Loralee B. Rupp, Nonna Akkerman, Nancy J. Oja-Tebbe, Talan Zhang, Alexandra Sitarik, Yan Wang, and Dana Larkin.

Center for Health Research, Geisinger Clinic, Danville, Pennsylvania:

Joseph A. Boscarino, Zahra S. Daar, Robert E. Smith, and Patrick J. Curry.

The Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii:

Vinutha Vijayadeva, Cynthia C. Nakasato, and John V. Parker.

The Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Portland, OR.

Mark A. Schmidt, Judy Donald, and Erin M. Keast.

Appendix 2

Chronic hepatitis B (HBV) cohort inclusion criteria:

-

HBV Criteria 1: Two or more ICD-9 diagnoses indicative of viral hepatitis B1 at least 6 months apart; or

-

HBV Criteria 2: A viral hepatitis B or chronic liver disease ICD-9 diagnosis (571.5 cirrhosis of liver without mention of alcohol, 456.0–456.1 esophageal varices, 789.59 other ascites, 155.0 liver cancer, V42.7 liver replaced by transplant, V49.83 awaiting organ transplant status) plus positive laboratory evidence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) or hepatitis B deoxyribonucleic acid (HBV DNA); or

-

HBV Criteria 3: Two or more positive laboratory results for HBsAg, hepatitis e-antigen (HBeAg), or HBV DNA, in any combination, occurring at least 6 months apart; or

-

HBV Criteria 4: A negative hepatitis B IgM core antibody (IgM anti-HBc) laboratory result concurrent or prior to a positive HBsAg or HBV DNA; or

-

HBV Criteria 5: A positive hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc) and positive HBsAg; or

-

HBV Criteria 6: A positive HBsAg and an elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) occurring at least 6 months apart.

-

1 Chronic hepatitis B International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems-9th Edition (ICD-9) codes: 070.22, 070.23, 070.32, 070.33; and acute/unspecified hepatitis B ICD-9 codes: 070.20, 070.21, 070.30, and 070.31.

Chronic Hepatitis C (HCV) cohort inclusion criteria:

-

HCV Criteria 1: Two or more ICD-9 diagnoses indicating viral hepatitis C1 at least 6 months apart; or

-

HCV Criteria 2: A viral hepatitis C1 or qualifying chronic liver disease ICD-9 diagnosis (571.5 cirrhosis of liver without mention of alcohol, 456.0–456.1 esophageal varices, 789.59 other ascites, 155.0 liver cancer, V42.7 liver replaced by transplant, V49.83 awaiting organ transplant status) separated at least 6 months apart from a positive anti-HCV laboratory result; or

-

HCV Criteria 3: A positive laboratory result for hepatitis C ribonucleic acid (HCV RNA) or HCV genotype.

-

1Chronic hepatitis C diagnosis ICD-9 codes: 070.44, 070.54, 070.70, 070.71; acute/unspecified hepatitis C ICD-9 codes: 070.41, 070.51.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, M., Rupp, L.B., Moorman, A.C. et al. Comparative Effectiveness Research of Chronic Hepatitis B and C Cohort Study (CHeCS): Improving Data Collection and Cohort Identification. Dig Dis Sci 59, 3053–3061 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-014-3272-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-014-3272-6