Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine the role of perceived control in moderating the effects of acculturative stress on the well-being of first generation Afghan married men refugees (N = 137, 25–50 years) residing in Lahore, Pakistan. The participants completed a survey questionnaire comprising a demographic information sheet, the Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Scale (Jibeen, Khalid, International Journal of Intercultural Relations 34:233–243, 2010), the Cognitive Stress Scale (Cohen et al., Journal of Health and Social Behavior 24:385–396, 1983), the Positive Affect & Negative Affect Schedule (Watson et al., Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 47:1063–1070, 1988), and the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., Journal of Personality Assessment 49:1–5, 1985). The results of moderated regression analyses revealed that perceived control can reduce the effect of stressful circumstances on satisfaction with life and increase positive psychological affect. The results could have implications for developing social and clinical therapeutic interventions towards a greater sense of self-determination and positive well-being to improve the refugees’ ability to take control of their lives.

Similar content being viewed by others

The international studies concerning refugees have examined clinical viewpoints and highlighted the impact of pre and post-migration experiences as factors which contribute to their subjective well-being (Guerin and Guerin 2007). Though much has been reported on refugees’ abilities to overcome distressing events in the countries where they seek asylum, little is known about their ability to positively adjust to everyday tasks and resettle and how this ability or lack of ability contributes to psychological disturbance.

The term refugee refers to a person who leaves his or her country of origin because of a natural disaster or war, political persecution, economic, or environmental deprivation (Tamang 2009; Ruiz and Bhugra 2010). Refugees have usually experienced shocking life events such as loss of home, family members and an uncertain future as their lives are precarious in new places. They want to escape from maltreatment in their country of origin and seek to find a new future in a new country (Tamang 2009).

The most enduring period of and migrations in human history involved 6.2 million Afghans leaving their native country to escape brutality and violence at various times from 1979 (Tamang 2009). The Soviet–Afghan war (December 1979–February 1989) and the power struggle after the collapse of the Soviet-backed Afghan government resulted in the devastation of socio-political norms in Afghanistan (Kassam & Ninji 2006). The first wave of Afghan migration into Pakistan started during 1980’s Soviet war in Afghanistan. Further, as a result of the Taliban movement in 1994, Pakistan welcomed over 1.7 million Afghan refugees. These refugees are under the protection and care of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and have been given permission by the Government of Pakistan to remain in the country indefinitely (United Nations High Commission for Refugees 2015).

It is important to note that one out of every four refugees worldwide is Afghan, with 95% located in Pakistan or Iran. 36% of the Afghan refugee population live in refugee camps or villages, while 63% live in urban settings throughout Pakistan (United Nations High Commission for Refugees 2015). These refugee camps are enclosed areas restricted to Afghan refugees and often lack even a very basic social infrastructure and economic development, in many cases, they have become permanent homes for refugees, in some cases for over 10 years (Dzeamesi 2008).

Psychological Adjustment of Refugees

Although there are a number of studies relating to the effects of pre-migration trauma on refugees’ mental health (Kinzie 2013; Mollica et al. 2014), and resettlement challenges (e.g., family separations, language problems, unemployment and discrimination) (Beiser 1999; Beiser and Hou 2001; Beiser et al. 2011), little research has attempted to investigate refugees’ psychological adjustment during their stay in refugee camps, which can be very prolonged. The idleness of life in a refugee camp has been reported to be particularly stressful and the negative psychosocial effects of living in a refugee camp are further exacerbated when the stay in the camp is prolonged (Kassam and Nanji 2006).

The term acculturative stress is related to acculturation, which is defined as the process of sociological and psychological adaptation of a newcomer to a country after living in it for some period of time (Poyrazli et al. 2010). The literature (e.g., Safdar et al. 2009; Sam and Berry 2016; Tartakovsky 2013) shows that poor acculturation may account for refugees having poor subjectively perceived well-being, because they face a constellation of acculturation-related stressors or challenges that demand coping responses. It is worth noting that refugees have to deal with both negative pre-migration as well as post migration experiences in the reception country and research suggests that the latter can have a greater effect on mental well-being than the former (e.g. Berry 1990; Beiser 1991; Liebkind 1996).

The common, world-wide post migration stressors that married refugees experience anywhere include discrimination, perceived threats to their ethnic identity, lack of opportunities for occupational and financial mobility, homesickness or a language barrier in the country of resettlement(Jibeen and Khalid 2010; Laban et al. 2005). It has been suggested (Miller and Rasco 2004) that dislocation frequently means separation from one’s community and even family members, which results in loneliness and loss of social support. They often experience loss of their social role and status as they have lost their jobs or access to land for farming, and hence their roles within their communities (Miller and Rasco 2004; Payne 1998; Wessels and Monteiro 2004; Schrijvers 1997; Ondeko and Purdin 2004). This situation in the host country may increase refugees’ distress and contribute to psychological problems such as negative affect, stress, or long-term depression (Kassam and Nanji 2006; Yakushko et al. 2008).

Research in the field of subjective well-being is of particular relevance to the study of refugees’ assessment of life in their host country as it helps to examine the psychological consequences of migration experiences. The research on subjective well-being has given priority to their emotional states which produce positive affect (e.g., happiness, pride, and satisfaction), negative affect (e.g., sadness or anxiety) and cognitive evaluation (life satisfaction) (Andrews and Withey 1976; Diener et al. 1997; Huebner and Dew 1996). The first two components refer to the emotional reactions to the circumstances of life, whereas cognitive evaluation (life satisfaction) involves a general appraisal of one’s life using subjective standards of what a good life is.

Perceived control is a type of cognitive resource whereby an individual focuses on his or her ability to effectively cope with the challenges or stressors s/he encounters (Bandura 1977, 2001). The studies (Glass and Singer 1972; Cohen 1980) on perceived control and stress clearly show that the after-effects of stress can significantly decrease if the individual concerned feels that s/he can take control of the stressors. Some of the literature (Luszczynska et al. 2005) suggests that perceived control as a psychological resource has been found to be particularly relevant to migrant populations as ethnic minorities may view themselves as being powerless and unable to maintain control over their daily lives (Hui 1982; Leung 2001). There are cross-cultural differences between collectivist and individualist cultures regarding the degree of perception of control (Hui 1982; Leung 2001). For example, Asians typically have a lower degree of perceived control than Europeans or Americans who have a higher degree of perception of control over their lives (Hui 1982; Leung 2001).

Theoretical Framework

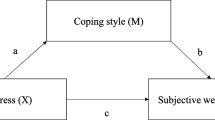

The life stress-health theory (Holmes and Rahe 1967) considers acculturative stress to be a risk factor and perceived control to be a resource factor. For instance, refugees with a higher level of perceived control of their environment take both positive and negative events as being under their personal control, while those with a lower perceived control think that such events are not related to their behavior (Kim 2002; Jibeen and Khalid 2010). In other words, acculturative stress is a risk factor for subjective well-being (e.g., positive affect, negative affect, satisfaction with life), but perceived control plays a moderating role between acculturative stress and subjective well-being (Berry et al. 1987; Betancourt et al. 2015; Jibeen and Khalid 2010; Lindert et al. 2009; Rothe and Pumariega 2005; Yakushko et al. 2008; Miller and Rasmussen 2010; Yongseok 2002; Williams and Berry 1991).

Though many studies have assessed the role of social resources in the acculturative stress and coping model (Maundeni 2001; McLachlan and Justice 2009), attempts to examine the role of personality factors as psychological resources remain relatively rare (Yamaguchi and Wiseman 2003; Wei et al. 2008). The current study extends the work on acculturative stress to a refugee camp context as many studies (Laban et al. 2005; Kassam and Nanji 2006; Yakushko et al. 2008) have examined the pre and post migration experiences of refugees (Jibeen and Khalid 2010; Laban et al. 2005), but few have focused on the experiences of long-term refugees residing in a refugee camp for many years as they have not been given naturalization or citizenship rights by the host country. Another purpose of this study is to introduce perceived (subjective) control (Kim 2002; Bandura 1977; Cohen 1980) as a possible explanatory factor in the relationship between acculturative stress and subjective well being (i.e. positive affect, negative affect and life satisfaction) in a sample of refugees living in refugee camps.

The following hypotheses were proposed in the present study.

Hypothesis 1

Acculturative stress significantly predicts subjective well being because:

a. There is a positive relationship between acculturative stress and negative affect.

b. There is a negative relationship between acculturative stress and positive affect, and acculturative stress and life satisfaction.

Hypothesis 2

The impact of acculturative stress on subjective well being (i.e.. positive affect, negative affect and life satisfaction) is moderated by perceived subjective control.

Methodology

Sample Inclusion Criteria

It is important to identify the factors that will enable the appropriate selection of subjects (e.g., age, marital status, duration of residence, etc.) to increase the external validity of any inferences to be drawn at the conclusion of the study. It would have been useful to include women in the study, but initial consultations indicated their response rate would be too low to have validity, hence men—as profiled—were the target cohort. In the present study, the sample included only married men (N = 137) with at least one child and participation was restricted to one individual from each family or household. The current study included only married men with children as they are at more risk of facing stressors like intergenerational difficulties and mental health problems than younger refugees, who tend to become acculturated and adapt to the receiving environment—in this case, the refugee camp—at a faster pace.

Measures

Instrument Translation

In the present study, the researcher expected that the majority of participants would have little knowledge of either English or Urdu, so using the method of forward and backward translation, all the scales were translated into Pushto (Brislin 1980; Brislin et al. 1973). To complete this process, one competent bilingual expert (competent in English and Pushto) translated the questionnaires into Pushto, then another professional translated the Pushto version back into English (back translation) and the two English versions were compared to establish consensus on the conceptual meaning of the phrases in this cultural context and check for accuracy and comprehensibility.

A demographic information sheet was used to collect background information on the subjects, together with the following four assessment tools.

Demographic Information Sheet

Demographic and migration related information (e.g., age, education, etc) was obtained from the participants. The participants also reported their level of satisfaction with their income on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from I (not at all satisfied) to 4 (very much satisfied), the total duration of their stay in Pakistan, and the level of their willingness to have migrated to Pakistan.

Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Scale

The Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Scale (MASS) was used to measure the level of acculturative stress of the Afghan refugees in the current study (Jibeen and Khalid 2010). The 24-item MASS measure of acculturative stress was adapted to the refugee context. In particular, the items were reworded to refer to Afghan refugees rather than Pakistani immigrants. The scale measures acculturative stress across five domains: discrimination (“I am constantly reminded of my minority status”), threat to ethnic identity (“I feel sad when I do not see my roots in this society”), lack of opportunities for occupational and financial mobility (“I have few opportunities to earn more income”), homesickness (“I miss my country and my country’s people”), and language-barrier (“I have difficulty in understanding Urdu in some situations”). The higher scores on each of these five domains represent greater perceived acculturative stress in the respective domain. The items of the MASS are rated on a 4-point Likert- type scale ranging from I (Disagree) to 4 (Agree). For scoring purposes, responses to the 24 items are summarized to yield a final composite score with a range from 24 to 96, the higher scores being indicative of greater perceived acculturative stress. The coefficient alpha reliability estimate for the 24-item MASS was.89 (Jibeen and Khalid 2010). In the current study, the coefficient alpha reliability was moderate (α = 0.86).

The Cognitive Stress Scale

The Cognitive Stress Scale (PSS) was used to measure respondents’ perceptions or evaluations of their control of collective life stressors (Cohen et al. 1983). The PSS is a 10-item measure of respondents’ cognitive perceptions or their evaluation of collective life stressors. Based on Lazarus’s concept of appraisal, it measures “the degree to which respondents found their lives unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloading” (Cohen et al. 1983, p. 387). The PSS not only measures the extent to which a given situation might be harmful but, also assesses how far this situation is controllable or not. The sample items include “In the last month, how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?” and “In the last month, how often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them?”. The PSS has a range of scores between 0 and 40 and the total score is calculated by taking the sum of 10 items. Higher scores on the PSS indicate a higher degree of perception of control over life circumstances. The coefficient alpha reliability estimate for the 10-item version of the PSS was moderate. 0.78 (Cohen et al. 1983). In the current study, the coefficient alpha reliability was moderate (α = 0.81).

The Positive Affect & Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS)

The Positive Affect and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), was used to measure the independent constructs of positive and negative affect (Cohen et al. 1983). The PANAS is composed of 20-items in total, 10 on a positive and 10 on a negative mood scale, so each is measured by 10-item. The participants were instructed to rate the level they had experienced each particular emotion within a specified time period, with reference to a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a lot). A number of different time-frames have been used with the PANAS, but in this study, the time-frame used was ‘during the past few weeks’. There were 10 items for each subscale under the topics of “interested”, “determined” “upset”, and “afraid”. The total scores were computed for each mood scale, with the lower scores representing the lower affect levels. The total scores for each scale can range from 10 to 50. Watson et al. (1988) found reliability (Cronbach’s α) between α = 0.84 and 0.87, with good concurrent and construct validity. In the current study, the coefficient alpha reliability estimates for negative affect (α = 0.85) and for positive affect (α = 0.82) were moderate.

The Satisfaction with Life Scale

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), (Diener et al. 1985) was used to measure the participants’ level of satisfaction with life. The SWLS is a 5-item measure of the judgmental component of subjective well-being. This scale allows participants to examine satisfaction with life domains using a 7-point scale that ranges from (7) strongly agree to (1) strongly disagree. The possible range of scores is 5–35, with a score of 20 representing a neutral point on the scale. The total scale score represents the respondent’s level of life satisfaction. The items include “In most ways, my life is close to my ideal”, and “I am satisfied with my life”. Higher scores on the SWLS indicate a higher degree of satisfaction while, low scores indicate dissatisfaction with life. The SWLS has been shown to have favorable psychometric properties, including high internal consistency and high temporal reliability. Further, the scale shows discriminant validity with other emotional subjective well-being measures (Diener et al. 1985). In the current study, the internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) for satisfaction with life was moderate (α = 0.87).

Ethical Considerations

Informed consent was obtained from each participant who agreed to participate in the study. They were informed that the overall testing session would take approximately 20–25 min, and their responses would be kept completely anonymous.

Data Collection and Data Analysis

The data were collected between May 2014 and August 2014. A total of 175 refugee men were approached according to the predetermined target profile to participate in the study, but only 137 participants formally agreed to participate. Thus, the response rate was 78%. The present study did not include data from women participants since their response rate was too low to have adequate representation.

The total sample was composed of 137 first generation Afghan men refugees (N = 137, 25–50 years old) residing in Afghan refugee communities in Lahore, one of the more cosmopolitan cities of Pakistan. The data were collected using face to face administration of the survey questionnaires, and the study was explained to the participants to be about their living circumstances, sources of stress and level of satisfaction while living in Pakistan. All the material was presented and completed in Pushto, and no payment was made to the participants. The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS statistic software package version 18.0.

Procedure

This study was approved by the Humanities Academic Review Committee for Research, COMSATS University, Lahore, Pakistan and there were no known conflicts of interest. The researcher consulted the representative or “Ammer-e-Jamaat” of the Afghan refugees with the help of the UNCHR refugee agency in Lahore, Pakistan, and he helped recruit the sample living in a refugee camp near “Sugian Pull” in Lahore, Pakistan. Data were collected between April 2014 and August 2014. Participation in the study was voluntary and only those participants who agreed to take part in the study were included. The data were collected using the purposive non-random sampling technique and informed consent was given before the questionnaires were completed face to face with the researcher, which took approximately 30 min for each questionnaire to be completed in one sitting.

Results

Table 1 presents several descriptive profile characteristics of the sample. The average age of the participants was 35.81 years (SD = 7.75) ranging from 25 to 50 years. The average length of respondents´ stay in Pakistan was 26.36 years (SD = 10.25). The mean number of participants’ children was 3.89 (SD = 1.95). In terms of their educational background, 23% of the sample identified themselves as illiterate, 28% reported having secondary education and 21% had some college education. Further, 20% of the sample had a master’s degree, but only 1% had a Ph.D. degree. Six participants did not report their education level. In terms of their current profession, 17% of the sample were unskilled laborers, 49% had a business and 31% identified themselves as skilled workers. Two participants did not give an answer about their profession (see Table 1) .Altogether 6 participants did not disclose their education level and 2 did not disclose their work or professions, so. to maintain the demographic and study variables, a missing values analysis was performed and the missing responses were replaced by the sample mean.

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations for all the variables of interest in this study. A correlational analysis indicates that acculturative stress was positively associated with negative affect (0.26, p < .01) and negatively with positive affect (− 0.25, p < .01) and satisfaction with life (− 0.37, p < .01). Further, perceived control was positively associated with satisfaction with life (0.35, p < .01), and positive affect (0.20, p < .05), while negatively with negative affect (− 0.19, p < .01) (Table 2).

Interaction Effects

A series of moderated regression analyses were performed to examine whether there were any moderating effects of perceived control on the relationship between acculturative stress and subjective well being (positive affect, negative affect and satisfaction with life). Given that moderated multiple regression is a conservative procedure (Young 2001), separate regression analyses were performed to maximize the power of the analyses. In these multiple regression analyses, demographic variables were entered as a block in step 1, acculturative stress variables in step 2 and perceived control in step 3. Finally, the cross product term (acculturative stress × perceived control) was entered in step 4 (Table 3). A significant increase in variance by a predictor variable represents a main effect for that variable, and a significant increase in variance by the product of two variables represents an interaction.

The analysis indicated that perceived control was a significant moderator in the relationship between acculturative stress and satisfaction with life (Table 3). When demographic variables were entered in step 1 as a block, they accounted for 27% of variance in satisfaction with life [F = (8, 121) = 2.57, p < .01]. In step 2, acculturative stress was the main effect (β = − 0.37, p > .001), accounting for 3% of the variance as the R value reached 30 from 27 [R2 = 0.30, F = (9, 120) = 4.01, p < .001]. In step 3, perceived control was also the main effect (β = 0.55, p > .001), accounting for 13% of the variance as the R value reached 43 from 30 (R2 = 0.43, F = (10, 119) = 6.85, p < .001). In the final step, the cross-product term (acculturative stress and perceived control) accounted for a significant level of variance in satisfaction with life (β = 0.73, p < .001), adding about 4% of variance as the R value reached 47 from 43 [R2 = 0.47, F = (11, 118) = 10.52, p < .001]. The results show that the beta value significantly increased from − 0.37 to 0.73% and the beta value changed the sign from negative to positive. This suggests that perceived control significantly buffered (B = 0.75, p < .05) the impact of acculturative stress on satisfaction in terms of increasing satisfaction with life and reducing acculturative stress.

The role of perceived control was also examined in the relationship between acculturative stress and positive affect (Table 3). In step 1, demographic variables accounted for 15% of variance [F = (8, 121) = 2.71, p < .001]. Acculturative stress was entered at step 2 and was a main effect (β = − 0.36, p < .001), accounting for 8% of the variance as the R value reached 23% from 15% [R2 = 0.23, F = (9, 120) = 4.05, p < .001]. This suggests that acculturative stress reduced positive affect. Further, perceived control was entered and was not a main effect (β = 0.12, p ≥ .05). In the final step, acculturative stress and cognitive control accounted for 3% of variance in positive affect (β = 0.91, p < .01) as the R2 value reached 26% from 23% (R2 = 0.27, F = (11, 118) = 3.92, p < .05). This suggests that perceived control significantly buffered (B = 0.91, p < .01) the impact of acculturative stress on positive affect in terms of increasing positive affect and reducing acculturative stress. The beta value significantly increased from − 0.36 to 0.91, changing from negative to positive, indicating that perceived control moderated (β = 0.91, p < .01) the impact of acculturative stress on positive affect in terms of increasing positive affect. Acculturative stress appears to be significantly negatively associated with positive affect (b = − 0.36), but perceived control plays a buffering role between acculturative stress and therefore changes the strength as well as the direction of acculturative stress and negative affect, and the relationship becomes positive.

Hypothesis regarding the moderating role of perceived control on the relationship between acculturative stress and negative affect was examined. In step 1, demographic variables accounted for 10% of the variance in negative affect, R2 = 0.10, F = (8, 121) = 1.70, p < .001. In step 2, acculturative stress was a main effect (β = 0.37, p < .001), accounting for 7% of variance as the R value reached 17% from 10% [R2 = 0.17, F = (9, 120) = 2.80, p < .001]. This suggests that acculturative stress increases negative affect. In step 3, perceived control was entered, but not indicated as a main effect (β = − 0.15, p ≥ .05). Further, in step 4, the interaction between acculturative stress and perceived control was significant, (β = − 0.96, p < .01), as it added a significant amount of variance (3%) in negative affect as the R2 value reached 22% from 19% [R2 = 0.22, F = (11, 118) = 2.87, p < .001]. This demonstrates that perceived control moderated (β = − 0.96, p < .01) the impact of acculturative stress on negative affect by reducing negative affect as the beta value significantly increased from 0.37 to − 0.96 and changed from positive to negative. Acculturative stress was significantly positively associated with negative affect (b = 0.37) but perceived control played a buffering role and changed the strength as well as the direction between acculturative stress and negative affect, thus causing the relationship to become negative.

Discussion

The results of this study support the hypotheses as tested on the first generation of Afghan married men refugees residing in a refugee camp in Lahore, Pakistan. The current study indicated that acculturative stress was positively associated with negative psychological symptoms, and negatively with satisfaction with life and positive affect. These findings are in line with the literature (Berry 2005; Tiburg and Vingerhoets 2007) suggesting that refugees experience greater acculturative stress and social pathology than immigrant groups in terms of freedom of choice as their migration has been involuntary, they have to undergo process of change and adjust to the unfamiliar environment of the refugee camp, detached from Pakistani society at large. Bhugra et al.’s (2010) study with refugees concluded that they develop severe and chronic emotional problems due to long exposure to trauma, loss of home, family members and friends and lack of social support. Further, refugees have to deal with situations that contrast with their cultural values and worldviews, language, food and traditions, paperwork and systems of business and currency (Berry et al. 2002).

In the current research acculturative stress was revealed as a major risk factor, reducing the refugees’ reduced positive functioning; the participants who perceived a higher level of acculturative stress had lower scores on positive affect as well as satisfaction with life, and higher scores on negative affect. These findings support by earlier research (Briggs and Macleod 2006) suggesting that acculturative stress affects the subjective well being of refugees by increasing psychological symptoms like depression, anxiety and psychosomatic symptoms. For example, Horn (2009) explored the emotional dilemmas that affected refugees in Kakuma refugee camp (northern Kenya) and found that they frequently suffering from feelings of hopelessness, fear, sadness, and anger or aggression. He reported that both current stressors and previous losses affected their emotional well-being. In another study, Wessels and Monteiro (2004) suggested that the effects of living in a refugee camp (typically a desperate, isolating and boring life) can be psychologically devastating as people report that they feel despondent and helpless even when their basic needs are fulfilled. Further, refugees in protracted displacement situations have to cope not only with prolonged exposure to the stresses of life in a refugee camp, but also with the ongoing uncertainty about their future (Feyissa and Horn 2008).

The current findings are in harmony with the literature (Luszczynska et al. 2005) indicating that individuals with a higher degree of perceived control have higher levels of positive affect as well as satisfaction with life; by contrast, individuals with a lower level of control have higher levels of negative affect and lower levels of positive affect as well as satisfaction with life. The present findings are in line with Van Selm et al. (1997) study conducted with Bosnian refugees living in Norway. It was found that higher locus of control and more positive reactions from the host society were significant factors that contributed to the higher life satisfaction of the refugees. In a recent study, Vukojeviu et al. (2016) found that a sense of control had a positive effect on mental health and all aspects of subjective well-being, while perceived discrimination and perceived multiple discrepancy negatively affected the subjective well-being and mental health of Serbian immigrants of the first generation in Canada.

In this study, perceived control moderated the relationship between acculturative stress and satisfaction with life because it helped clarify the variance in satisfaction with life over and above the acculturative stress of the Afghan refugees. Further, the present study also indicates that perceived control significantly buffered the impact of acculturative stress on positive as well as negative affect. The perceived control variable significantly contributed to explaining variance in terms of increasing positive affect and decreasing negative affect. It shows that though acculturative stress determines an individual’s level of emotional health, the degree of perception of control over their environment plays a central role in providing mechanisms and processes through which this relationship is expressed (Lee 2005; Lee et al. 2004). The literature (e.g., Luthar et al. 2000) suggests that the presence or absence of psychological or social resources, collectively known as protective factors (e.g., cognitive abilities), determine outcome variability in the context of adverse circumstances. These protective factors operate to reduce maladjustment and psychopathology and promote psychological, emotional, and behavioral competence and well-being. For example, a recent meta-analysis of 51 studies on the role of coping resources in immigrants’ psychological adjustment found evidence of a moderate effect, in that greater levels of positive self-concept, and confidence and beliefs in one’s competencies were connected to lower depression and anxiety (Lee and Ahn 2012). Further, Diwan et al.’s 2004 study of Asian and Salvadoran refugees suggested that when individuals face challenges in their lives, they use personal coping resources as the keys to reducing the adverse effects of migration stress to overcome difficulties and enhance life satisfaction.

The present research illustrates how individual differences can increase or decrease the risk of developing emotional problems by affecting the manner in which individuals react to stress. Those refugees that believe they can overcome past trauma demonstrate a pro-active coping ability to regain control over their lives rather than having their lives dictated by adverse circumstances. We assume that those having lower degrees of perception of control over their lives usually flow in the directions controlled by forces beyond their control, while those in the former group explore new options and believe that the situation—at least in part—is within their control. They are active and can change their strategies to achieve certain goals or even change the goals themselves (Kramer 2006).

The current findings only partially support the universal applicability of the perceived control construct as they had no significant main effect on positive or negative affect. As locus of control is highly influenced by culture, researchers like Church (1982), Ward and Kennedy (1992) have suggested that the impact of locus of control on psychological adjustment should be viewed within its socio cultural context. It has been found that in some cultures, a lower degree of perceived control may actually be healthy or adaptive (Leung 2001b).

Researchers like Ward and Kennedy (1992) have noted that although Asians have a lower degree of control over their lives compared to Europeans, they do not demonstrate worse subjective well-being during cultural transitions. As the present Afghan refugee sample has roots in Asian culture, perceived control may not be as important enough to decrease negative affect or increase positive affect. There have been several explanations for the decreased degree of control seen in the Asian cultures like Afghanistan and Pakistan. For example, in collectivist cultures, people tend to defer to the wishes of others, thereby decreasing their life control and choices, which are related to perceived control. Further, a lower degree of control orientation is also in line with the belief in fate and destiny, which are an important part of traditional Asian cultural values (Dyal 1984). It is important to note that developing an external locus of control can not only reflect the reality of the lives of minority members of society or refugees, but can also protect them from blaming themselves for those difficulties, for limited success and failures that they face in the host culture (as cited in Uba 1994).

Limitations

The limitations of this study include its relatively small sample size, lack of generalizability, sampling bias, problems related to a cross-sectional study, and use of instruments. Moreover, it is important for the reader to know that the current study data are correlational in nature and other possible models could also have been tested on the current study data. Therefore, replication of the study with a larger sample is suggested as this could provide more credible or powerful evidence to reject the null hypothesis, so providing the foundation for informed scientific knowledge (Maxwell 2004). As the current study was based on a sample drawn from a narrowly defined population (i.e., male married Afghan refugees 25–50 years old) samples from diverse populations with slightly different procedures and multiple dependent variables would help the generalizability of the results. Further, information like their past psychiatric history or the number of close friends they have in the host country was not obtained from the participants, which could affect their emotional condition or level of satisfaction. The successful management of refugees’ new social environment in the presence or absence of their traditional social networks may be related to their emotional health. In the present study, not enough of the Afghan women approached agreed to participate in the study and therefore, they are not represented in the data or results. The findings related to the insignificant main effect of perceived control on positive or negative affect might have been different if data from Afghan women had been available. Consequently, as the present study included only male participants, it is not known whether the current model and findings apply to both genders.

Implications

Despite its limitations, the present findings can help social workers, researchers and policy makers recognize the resource factors that could help a refugee community to establish and maintain positive functioning. The first and foremost need is to support refugees so that they can “develop a sense of stability, safety, and trust to regain a sense of control over their lives” (Ehntholt and Yule 2006, p. 1202). Though an individual’s personality cannot be changed, if that individual realizes that their perception of stress influences how distress causes him or her to pursue maladaptive coping resulting, he or she can take positive steps towards learning new and more adaptive coping styles.

It is also important to recognize that the needs of refugees from widely different cultural and ethnic backgrounds may be quite different (Measham et al. 2005).The literature suggests (e.g. Sue et al. 2009) that work with refugees requires cultural competence and it is important for practitioners to be aware of their own cultural beliefs and values. Further, they should have knowledge of clients’ culture, beliefs, and personal histories and possess the skills to intervene in clinically meaningful and appropriate ways. This study aims to prompt researchers and counselors to take account of and address the cultural beliefs and personal histories, including the multiple losses and traumas, Afghan refugees may have experienced before and upon leaving their native country, which may remain unacknowledged and unresolved. Further, public health clinics and private hospitals can provide an environment where counselors or psychologists, as part of interdisciplinary teams with physicians and nurses, may assess the Afghan refugees’ mental and physical responses to stressors and combine basic social work services and psychological techniques to mediate their stress-related problems. For example, in addition to the approaches that have been tested, alternative approaches may include the use of traditional healers, family or community-based approaches, and cross-disciplinary collaboration (Miller and Rasco 2004).

After resettlement in a new environment, refugee clients may struggle to defeat not only the long-term psychological impacts of threats to their personal safety and social and cultural dislocation, but also additional social, linguistic, educational and vocational challenges and their accompanying acculturative stresses. Therefore, the government agencies and service providers dealing with Afghan refugees need to consider their educational level as well as their previous occupation in their homeland and support English/Urdu language training here in Pakistan to offer them assistance in seeking work in the wider Pakistani community. The social and community-based approaches that address natural coping resources and strategies - family cohesion, education, and empowerment - are likely to be the most helpful interventions to enhance Afghan refugees’ capacity to regain control of their own lives.

References

Andrews, F. M., & Withey, S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being: American’s perception of life quality. New York: Plenum.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1–26.

Beiser, M. (1991). The mental health of refugees in resettlement countries. In H. Adelman (Ed.), Refugee policy: Canada and the United States (pp. 425–442). Toronto: York Lanes Press.

Beiser, M. (1999). Strangers at the gate: The “boat people’s” first ten years in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Beiser, M., & Hou, F. (2001). Language acquisition, unemployment and depressive disorder among Southeast Asian refugees: A 10-year study. Social Science & Medicine, 53(10), 1321–1334.

Beiser, M., Simich, L., Pandalangat, N., Nowakowski, M., & Tian, F. (2011). Stresses of passage, balms of resettlement and PTSD among Sri Lankan Tamils in Canada. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56(6), 333–340.

Berry, J. W. (1990). Psychology of acculturation. In J. Berman (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation, 1989: Cross-cultural perspectives. Current theory and research on motivation, Vol. 37 (pp. 201–234). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Berry, J. W. (2005). Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29, 697–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.013.

Berry, J. W., Kim, U., Minde, T., & Mok, D. (1987). Comparative studies of acculturative stress. International Migration Review, 21, 491–511. https://doi.org/10.2307/2546607.

Berry, J. W., Poortinga, Y. H., Segall, M. H., & Dasen, P. R. (2002). Cross-cultural psychology: Research and applications (2nd edn.). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Betancourt, T. S., Abdi, S., Ito, B. S., Lilienthal, G. M., Agalab, N., & Ellis, H. (2015). We left one war and came to another: Resource loss, acculturative stress, and caregiver-child relationships in Somali refugee families. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21(1), 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037538.

Bhugra, D., Craig, T., & Bhui, K. (2010). The mental health of refugees and asylum seekers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Briggs, L., & Macleod, A. (2006). Demoralization-A useful conceptualization of non-specific psychological distress among refugees attending mental health services. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 52(6), 512–524. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764006066832.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In H. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (pp. 389–444). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Brislin, R. W., Lonner, W. J., & Throndike, R. M. (1973). Cross cultural research methods. New York: Wiley.

Church, A. T. (1982). Sojourner adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 91, 540–572.

Cohen, S. (1980). After-effects of stress on human performance and social behavior: A review of research and theory. Psychological Bullefin, 88, 82–108.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of cognitive stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 1–5.

Diener, E., Suh, E., & Oishi, S. (1997). Recent findings on subjective well being. Indian Journal of Clinical Psychology, 24, 25–41.

Diwan, S., Jonnalagadda, S. S., & Balaswamy, S. (2004). Resources predicting positive and negative affect during the experience of stress: A study of older Asian Indian immigrants in The United States. The Gerontologist, 44(5), 605–614. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/44.5.605.

Dyal, J. A. (1984). Cross-cultural research with the locus of control constructs. In H. M. Lefcourt (Ed.), Research with the locus of control constructs (pp. 209–306). New York: Academic Press.

Dzeamesi, M. (2008). Refugees, the UNHCR and host governments as stake‐holders in the transformation of refugee communities: A study into the Buduburam refugee camp in Ghana. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 4(1), 28–41. https://doi.org/10.1108/17479894200800004.

Ehntholt, K. A., & Yule, W. (2006). Practitioner review: Assessment and treatment of refugee children and adolescents who have experienced war-related trauma. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(12), 1197–1210.

Feyissa, A., & Horn, R. (2008). There is more than one way of dying: An Ethiopian perspective on the effects of long- term tays in refugee camps. In: D. Hollenbach (Ed) Refugee rights: Ethics, advocacy and Africa. Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

Glass, D. C., & Singer, J. E. (1972). Urban stress: Experiments on noise and social stressors. New York: Academic Press.

Guerin, P., & Guerin, B. (2007). Families, communities and migration: What exactly changes? University of Waikato-New Zealand. Retrieved http://www.waikato.ac.nz/wfass/migration/docs/guerin-families communitiesmigration.pdf.

Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomtic Research, 11(2), 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4.

Horn, R. (2009). A study of the emotional and psychological well-being of refugees in kakuma refugee camp, Kenya. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 5(4), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.5042/ijmhsc.2010.0229.

Huebner, E. S., & Dew, T. (1996). The interrelationship of positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction in an adolescent sample. Social Indicators Research, 38, 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00300455.

Hui, C. H. (1982). Locus of control: A review of cross-cultural research. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 6, 301–323.

Jibeen, T., & Khalid, R. (2010). Development and preliminary validation of multidimensional acculturative stress scale for Pakistani immigrants in Toronto, Canada. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 34, 233–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.09.006.

Kassam, A., & Nanji, A. (2006). Mental health of Afghan refugees in Pakistan: A qualitative rapid reconnaissance field study Intervention. Retrieved from http://www.ourmediaourselves.com/archives/41pdf/kassam.pdf.

Kim, M. T. (2002). Measuring depression among Korean Americans: Development of the Kim Depression Scale for Korean Americans. Journal of Trans cultural Nursing, 13, 110–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/104365960201300203.

Kinzie, J. D. (2013). The traumatic lives of refugees and asylum seekers. GP Solo, 30(5), 42–44.

Kramer, S. (2006). Forced migration and mental health in rethinking the care of refugees and displaced persons. In D. Ingleby (Ed.), Getting closer: Methods of research with refugees and asylum seekers (pp. 129–148). Netherlands: Springer.

Laban, C. J., Gernaat, H. B., Komproe, I. H., van der Tweel I., & De Jong, J. T. (2005). Postmigration living problems and common psychiatric disorders in Iraqi asylum seekers in the Netherlands. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 193(12), 825–832.

Lee, D. L., & Ahn, S. (2012). Discrimination against Latina/os: A meta-analysis of individual-level resources and outcomes. The Counseling Psychologist, 40, 28–65.

Lee, J. S., Koeske, G. F., & Sales, E. (2004). Social support buffering of acculturative stress: A study of mental health symptoms among Korean international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 28, 399–414.

Lee, R. M. (2005). Resilience against discrimination: Ethnic identity and other-group orientation as protective factors for Korean Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(10), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.1.36.

Leung, C. (2001). The psychological adaptation of overseas and migrant students in Australia. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 36(4), 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590143000018.

Liebkind, K. (1996). Acculturation and stress: Vietnamese refugees in Finland. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology, 27, 161–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022196272002.

Lindert, J., Ehrenstein, O. S., Priebe, S., Mielck, A., & Brahler, E. (2009). Depression and anxiety in labor migrants and refugees-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 69(2), 246–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.032.

Luszczynska, A., Gutierrez-Dona, B., & Schwarzer, R. (2005). General self-efficacy in various domains of human functioning: Evidence from five countries. International Journal of Psychology, 40, 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590444000041.

Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). Research on resilience: Response to commentaries. Child Development, 71, 573–575.

Maundeni, T. (2001). The role of social networks in the adjustment of African students to British society: Students’ perceptions. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 4(3), 253–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613320120073576.

Maxwell, S. E. (2004). The persistence of underpowered studies in psychological research: Causes, consequences, and remedies. Psychological Methods, 9, 147–163. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.9.2.147.

McLachlan, D. A., & Justice, J. (2009). A grounded theory of international student well-being. Journal of Theory Construction & Testing, 13(1), 27–32.

Measham, T., Rousseau, C., & Nadeau, L. (2005). The development and therapeutic modalities of a transcultural child psychiatry service. The Canadian Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Review, 14(3), 68–72.

Miller, K. E., & Rasco, L. M. (Eds.). (2004). The mental health of refugees: Ecological approaches to healing and adaptation. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Miller, K. E., & Rasmussen, A. (2010). War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Social Science & Medicine, 70(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.02.

Mollica, R. F., Brooks, R., Tor, S., Lopes-Cardozo, B., & Silove, D. (2014). The enduring mental health impact of mass violence: A community comparison study of Cambodian civilians living in Cambodia and Thailand. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 60(1), 6–20.

Ondeko, R., & Purdin, S. (2004). Understanding the causes of gender-based violence. Forced Migration Review, 19, 1–30.

Payne, L. (1998). Food shortage and gender relations in Ikafe settlement, Uganda. Gender and Development, 6, 30–36.

Poyrazli, S., Thukral, R. K., & Duru, E. (2010). International student’s race-ethnicity, personality, and acculturative stress. Journal of Psychology and Counseling, 2(8), 25–32.

Rothe, E., & Pumariega, J. B. (2005). Mental health of immigrants and refugees. Community Mental Health Journal, 41(5), 581–597. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-005-6363-1.

Ruiz, P., & Bhugra, D. (2010). Refugees and asylum seekers: Conceptual issues. In D. Bhugra, T. Craig & K. Bhui (Eds.), Mental health of refugees and asylum seekers (pp. 1–8). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Safdar, S., Struthers, W., & van Oudenhoven, J. P. (2009). Acculturation of Iranians in the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 40(3), 468–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022108330990.

Sam, D. L., & Berry, J. W. (2016). The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology (2nd edn.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schrijvers, J. (1997). Internal refugees in Sri Lanka: The interplay of ethnicity and gender. European Journal of Development Research, 9, 62–82.

Sue, S., Zane, N., Nagayama, G. C., & Berger, L. K. (2009). The case for cultural competency in psychotherapeuticinterventions. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 525–548. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163651.

Tamang, R. (2009). Afghan forced migration: Reaffirmation, redefinition, and the politics of aid. Asian Social Science, 5(1), 3–12

Tartakovsky, T. (2013). Immigration: Policies, challenges and impact. Hauppauge: Nova Science.

Tiburg, M. V., & Vingerhoets, A. (2007). Psychological aspects of geographical moves: Homesickness and acculturation. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Uba, L. (1994). Asian Americans: Personality patterns, identity, and mental health. New York: Gulford Press.

United Nations High Commission of Refugees. (2015). Facts and figure about refugees. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org.uk/about-us/key-facts-and-figures.html.

Van Selm, K., Sam, D. L., & Van Oudenhoven, J. P. (1997). Life satisfaction and competence of Bosnian refugees in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 38(2), 143–149.

Vukojeviu, V., Kuburiu, Z. & Damjanoviu, A. (2016). The influence of perceived discrimination, sense of control, self-esteem and multiple discrepancies on the mental health and subjective well-being in Serbian immigrants in Canada. Psihologija, 49(2), 105–127.

Ward, C., & Kennedy, A. (1992). Locus of control, mood disturbance and social difficulty during cross-cultural transitions. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 16, 175–194.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 47, 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063.

Wei, M., Ku, T., Russell, D. W., & Mallinckrodt, B. (2008). Moderating effects of three coping strategies and self-esteem on perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms: A minority stress model for Asian international students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55(4), 451–462.

Wessels, M., & Monteiro, C. (2004). Internally displaced Angolans: A child-focused, community based intervention. In K. E. Miller & L. M. Rasco (Eds.), The mental health of refugees: Ecological approaches to healing and adaptation. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaoum.

Williams, C. L., & Berry, J. W. (1991). Primary prevention of acculturative stress among refugees: Application of psychological theory and practice. American Psychologist, 46, 632–641.

Yakushko, O., Watson, M., & Thompson, S. (2008). Stress and coping in the lives of recent immigrants and refugees: Considerations for counseling. International Journal for the Advancement of Counseling, 30, 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-008-9054-0.

Yamaguchi, Y., & Wiseman, R. L. (2003). Locus of control, self-construals, intercultural communication effectiveness, and psychological health of international students in the United States. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 32(4), 227–245.

Yongseok, K. (2002). The role of perceived control in moderating the effect of stressful circumstances among Korean immigrants. Health & Social Work, 27(1), 36–46.

Young, M. Y. (2001). Moderators of stress in Salvadoran refugees: The role of personal and social resources. International Migration Review, 35(3), 840–869.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jibeen, T. Subjective Well-Being of Afghan Refugees in Pakistan: The Moderating Role of Perceived Control in Married Men. Community Ment Health J 55, 144–155 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-018-0342-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-018-0342-9