Abstract

Neural machine translation is increasingly being promoted and introduced in the field of translation, but research into its applicability for post-editing by human translators and its integration within existing translation tools is limited. In this study, we compare the quality of SMT and NMT output of the commercially-available interactive and adaptive translation environment Lilt, as well as the translation process of professional translators working with both versions of the tool, their preference for SMT vs. NMT for post-editing, and their attitude towards such an interactive and adaptive translation tool compared to their usual translation environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note: In their study they made use of translation students, not professional translators.

The termbase contains 360 English–Dutch term pairs and was compiled for a medical translation course at Ghent University.

References

Barrachina S, Bender O, Casacuberta F, Civera J, Cubel E, Khadivi S, Lagarda A, Ney H, Tomás J, Vidal E et al (2009) Statistical approaches to computer-assisted translation. Comput Linguist 35(1):3–28

Bentivogli L, Bertoldi N, Cettolo M, Federico M, Negri M, Turchi M (2016) On the evaluation of adaptive machine translation for human post-editing. IEEE/ACM Trans Audio Speech Lang Process 24(2):388–399. https://doi.org/10.1109/TASLP.2015.2509241

Bentivogli L, Bisazza A, Cettolo M, Federico M (2016) Neural versus phrase-based machine translation quality: a case study. In: Proceedings of the 2016 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing, Association for Computational Linguistics, Austin, Texas, pp 257–267

Castilho S, Moorkens J, Gaspari F, Calixto I, Tinsley J, Way A (2017) Is neural machine translation the new state of the art? Prague Bull Math Linguist 108:109–120

Daems J, Vandepitte S, Hartsuiker R, Macken L (2017) Identifying the machine translation error types with the greatest impact on post-editing effort. Front Psychol 8:15

Elming J, Winther Balling L, Carl M (2014) Investigating user behaviour in post-editing and translation using the CASMACAT workbench. In: O’Brien S, Winther Balling L, Carl M, Simard M, Specia L (eds) Post-editing of machine translation: processes and applications. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Cambridge, pp 147–170

Federico M, Cattelan A, Trombetti M (2012) Measuring user productivity in machine translation enhanced computer assisted translation. In: Proceedings of the tenth conference of the association for machine translation in the Americas (AMTA). AMTA Madison, WI, pp 44–56

Gaspari F, Toral A, Naskar SK, Groves D, Way A (2014) Perception vs reality: measuring machine translation post-editing productivity. In: Proceedings of the third workshop on post-editing technology and practice

Green S, Chuang J, Heer J, Manning CD (2014) Predictive translation memory: a mixed-initiative system for human language translation. In: Proceedings of the 27th annual ACM symposium on User interface software and technology. ACM, New York, pp 177–187

Leijten M, Van Waes L (2013) Keystroke logging in writing research: using Inputlog to analyze and visualize writing processes. Writ Commun 30(3):358–392

Moorkens J, O’Brien S (2017) Assessing user interface needs of post-editors of machine translation. In: Human issues in translation technology. Routledge, pp 127–148

O’Brien S (2012) Translation as human-computer interaction. Transl Spaces 1(1):101–122

Ortiz-Martínez D, Leiva LA, Alabau V, García-Varea I, Casacuberta F (2011) An interactive machine translation system with online learning. In: Proceedings of the 49th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: human language technologies: systems demonstrations. Association for Computational Linguistics, pp 68–73

Peris Á, Casacuberta F (2018) Online learning for effort reduction in interactive neural machine translation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.03594

Peris Á, Domingo M, Casacuberta F (2017) Interactive neural machine translation. Comput Speech Lang 45:201–220

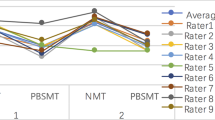

Shterionov D, Superbo R, Nagle P, Casanellas L, O’Dowd T, Way A (2018) Human versus automatic quality evaluation of NMT and PBSMT. Mach Transl 32(3):217–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10590-018-9220-z

Snover M, Dorr B, Schwartz R, Micciulla L, Makhoul J (2006) A study of translation edit rate with targeted human annotation. In: Proceedings of association for machine translation in the Americas

Teixeira CS (2014) Perceived vs. measured performance in the post-editing of suggestions from machine translation and translation memories. In: Proceedings of the third workshop on post-editing technology and practice, p 45

Teixeira CS, O’Brien S (2017) Investigating the cognitive ergonomic aspects of translation tools in a workplace setting. Transl Spaces 6(1):79–103

Tezcan A, Hoste V, Macken L (2017) SCATE taxonomy and corpus of machine translation errors. In: Pastor GC, Durán-Muñoz I (eds) Trends in E-tools and resources for translators and interpreters, approaches to translation studies, vol 45, Brill — Rodopi, pp 219–244

Tiedemann J (2009) News from OPUS—-a collection of multilingual parallel corpora with tools and interfaces. In: Nicolov N, Bontcheva K, Angelova G, Mitkov R (eds) Recent advances in natural language processing, vol V. John Benjamins, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, pp 237–248

Toral A, Sánchez-Cartagena VM (2017) A multifaceted evaluation of neural versus phrase-based machine translation for 9 language directions. In: Proceedings of the 15th conference of the European chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: volume 1, long papers, Association for Computational Linguistics, Valencia, Spain, pp 1063–1073

Van Brussel L, Tezcan A, Macken L (2018) A fine-grained error analysis of NMT, SMT and RBMT output for English-to-Dutch. In: Proceedings of the eleventh international conference on language resources and evaluation (LREC 2018), European Language Resources Association (ELRA), Miyazaki, Japan, pp 3799–3804

Wang W, Peter JT, Rosendahl H, Ney H (2016) CharacTer: translation edit rate on character level. In: Proceedings of the first conference on machine translation: volume 2, shared task papers. Association for Computational Linguistics

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A SMT and NMT sentences post-editing preference study

Appendix A SMT and NMT sentences post-editing preference study

The following is an overview of the sentences used in the perceived usability study. The English source sentence is given, followed by the NMT suggestion and SMT suggestion. The accuracy (ACC) and fluency (FLU) errors are indicated below the MT output. The problematic passages in the MT output are indicated in bold.

S1 | Terrosa should not be used in growing adults. |

NMT | Terrosa mag niet worden gebruikt bij volwassen volwassenen. |

\(\rightarrow \) ACC: mistranslation multi-word expression (growing adults) | |

\(\rightarrow \) FLU: repetition (volwassen volwassenen) | |

SMT | Terrosa mag niet worden gebruikt bij volwassenen groeien. |

\(\rightarrow \) ACC: mistranslation multi-word expression (growing adults) | |

\(\rightarrow \) FLU: missing function word (volwassenen [die] groeien) | |

S2 | You have been given this medicine to lower the number of fits (seizures) you have. |

NMT | U heeft dit geneesmiddel gekregen om het aantal toevallen (zure aanvallen) te verlagen. |

\(\rightarrow \) ACC: mistranslation - semantically unrelated (zure) [En: acid] | |

\(\rightarrow \) FLU: lexical choice (zure) | |

SMT | Je hebt het geneesmiddel toegediend heeft gekregen een lager aantal aanvallen (toevallen). |

\(\rightarrow \) ACC: mistranslation other (been given \(\rightarrow \) ‘gekregen’; not ‘toegediend gekregen’) | |

\(\rightarrow \) FLU: repetition (hebt/heeft) + structural problem |

S3 | Your doctor will advise you on what care you need to take during Skilarence treatment. |

NMT | Uw arts zal u adviseren over de zorg die u moet nemen tijdens de behandeling met Skilarece. |

\(\rightarrow \) ACC: named entity (Skilarece) | |

\(\rightarrow \) FLU: lexical choice (moet nemen) | |

SMT | Uw arts zal u vertellen hoe u de Skilarence tijdens behandeling. |

\(\rightarrow \) ACC: omission (on what care you need to take) | |

\(\rightarrow \) FLU: extra word (de) + missing verb (hoe u ...[moet nemen]) | |

S4 | Depending on the results of these blood and urine tests, your doctor may |

reduce your dose of Skilarence or stop treatment. | |

NMT | Afhankelijk van de resultaten van deze bloed- en urinetests kan uw arts uw dosis |

Skilarece of stop met de behandeling. | |

\(\rightarrow \) ACC: omission (reduce) | |

\(\rightarrow \) FLU: missing verb + verb form (stop \(\rightarrow \) stoppen) + named entity (Skilarece) | |

SMT | Afhankelijk van de resultaten van deze bloed - en urinetesten kan uw arts uw dosering reducerenvan Skilarence of de behandeling te stoppen. |

\(\rightarrow \) FLU: spelling (bloed - en urinetesten) + word order (uw dosering van Skilarece reduceren) + extra word (te) | |

S5 | It changes the activity of the immune system and reduces the production of substances involved in causing psoriasis. |

NMT | Het verandert de werking van het immuunsysteem en vermindert de productie van stoffen die bij het veroorzaken van psoriasis zijn betrokken. |

\(\rightarrow \) FLU: structural problem | |

SMT | Het verandert de activiteit van het immuunsysteem en vermindert de productie van stoffen die bij psoriasis. |

\(\rightarrow \) ACC: omission (involved in causing) | |

\(\rightarrow \) FLU: missing verb (die bij psoriasis [betrokken zijn]) | |

S6 | You have thoughts of harming or killing yourself. |

NMT | U hebt gedachten over het beschadigen of doden van uzelf. |

\(\rightarrow \) FLU: word order | |

SMT | Je gedachten hebben over zelfbeschadiging of zelfmoord. |

\(\rightarrow \) FLU: agreement (je ...hebben \(\rightarrow \) je ...hebt) | |

S7 | Tell your doctor if you have or have had problems with your stomach or intestines. |

NMT | Vertel het uw arts als u problemen heeft gehad met uw maag of darmen. |

\(\rightarrow \) ACC: omission (have or) | |

SMT | Vertel het uw arts als u al eerder problemen hebt gehad met uw maag of darmen. |

\(\rightarrow \) ACC: omission (have or) | |

S8 | Dimethyl fumarate works on cells of the immune system (the body’s natural defences). |

NMT | Dimethylfumaraat werkt op cellen van het immuunsysteem (de natuurlijke afweer van het lichaam). |

\(\rightarrow \) FLU: lexical choice (afweer) | |

SMT | Dimethyl, werken op cellen van het immuunsysteem (het natuurlijke afweersysteem van het lichaam). |

\(\rightarrow \) ACC: omission (fumarate) | |

\(\rightarrow \) FLU: agreement (Dimethyl, werken \(\rightarrow \) Dimethyl werkt) + punct (comma) | |

S9 | These may be signs there is too much calcium in your blood. |

NMT | Dit kunnen tekenen zijn die er te veel calcium in uw bloed zijn. |

\(\rightarrow \) FLU: 2x agreement (die \(\rightarrow \) dat; zijn \(\rightarrow \) is) |

SMT | Dit kunnen tekenen zijn dat er teveel calcium in uw bloed |

\(\rightarrow \) FLU: missing verb + spelling (teveel \(\rightarrow \) te veel) | |

S10 | – if you have continuing nausea, vomiting, constipation, low energy, or muscle weakness. |

NMT | – als u nausea, braken, constipatie, lage energie of spierzwakte heeft. |

\(\rightarrow \) ACC: omission (continuing) | |

\(\rightarrow \) FLU: lexical choice (lage energie \(\rightarrow \) weinig energie) + multi (als u ...heeft \(\rightarrow \) als u last heeft van ...) | |

SMT | – als u aanhoudende misselijkheid, braken, constipatie, lage energie of spierzwakte. |

\(\rightarrow \) ACC: omission (have) | |

\(\rightarrow \) FLU: missing verb + lexical choice (lage energie \(\rightarrow \) weinig energie) |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Daems, J., Macken, L. Interactive adaptive SMT versus interactive adaptive NMT: a user experience evaluation. Machine Translation 33, 117–134 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10590-019-09230-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10590-019-09230-z