Abstract

Results-based funding (RBF) is a governance concept that is rapidly becoming the mainstream paradigm for international collaborations in the environmental sector. While portrayed as a compromise solution between market-based mechanisms and unconditional donations, the implementation of RBF is revealing new conflicts and contradictions of its own. This paper explores the application of RBF for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) by describing the discursive conflicts between recipient (i.e., Brazil) and donor (i.e., Norway and Germany) countries of the Amazon Fund about what constitutes “results” or “performance.” Although all parties agree that the financial transfers to RBF should be based on past emission reductions in relation to a historical baseline, they hold clashing interpretations about temporal (i.e., past or future) and epistemological (i.e., how to measure) aspects of the results these payments are intended for. Firstly, while Brazil emphasizes that it deserves a reward of USD 21 billion for results achieved between 2006 and 2016, donor countries have indicated an interest in paying only for most recent results as a way to incentivize further reductions. Secondly, while all parties believe that Amazon Fund should support policies to reduce deforestation, donor countries have revealed concerns that the performance of the Amazon Fund projects in generating further reductions has not been measured in a rigorous manner. This suggests that donor countries may consider making changes to current RBF mechanisms or getting involved in new forms of finance.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

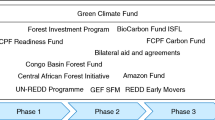

One of the challenges of international and national forest governance involves the establishment of financial instruments that contribute to the attainment of results. Over the last decade, the concept of Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) partially abandoned an initial strong emphasis on market instruments for offsetting carbon emissions in favor of a result-based funding (RBF) approach that financially rewards historical emissions reductions (Carvalho 2012; Van der Hoff et al. 2015). Even though international agreements, including the Warsaw Framework for REDD+ in 2013 (see decision 13/CP. 19) and the Paris Agreement in 2015 (i.e., art. 6), might still allow REDD+ offsets, there are many uncertainties about its viability (Streck et al. 2017; Voigt and Ferreira 2015). Furthermore, the substantial bilateral investments made by Norway and Germany as well as the approval in October 2017 of USD 500 million from the Green Climate Fund (GCF) for REDD+ further consolidate this approach (Den Besten et al. 2014; Turnhout et al. 2016; Voigt and Ferreira 2015). Although the use of RBF as a financial instrument for policy-making is already extensively applied and evaluated (Broom 1995; Eldridge and Palmer 2009; Oxman and Fretheim 2008), its development and application in the context of REDD+ is only emerging in international and national forest governance (Brockhaus et al. 2015; Norman and Nakhooda 2014). In this context, the Brazilian Amazon Fund is currently one of the largest and most experienced RBF instruments worldwide, with over a decade of operational activity, up to USD 2 billion in donation pledges, and an approved disbursement of over USD 707 million for the support of 100 projects (BNDES 2018). At the same time, scholars are slowly beginning to observe the emergence of critiques on the Amazon Fund’s effectiveness with respect to reducing deforestation (Angelsen 2017; Hermansen et al. 2017).

This paper aims to contribute to understanding the challenges and conflicts involved in the construction of RBF instruments by juxtaposing the discourses of both investor and recipient countries related to the Amazon Fund. More specifically, it focuses on diverging interpretations of what could count as “results” that form the basis for financial transactions and effectiveness evaluations of the Amazon Fund. As managerial approaches for environmental governance become increasingly commonplace, an analysis of the political conflicts involved is a useful step towards enhancing the legitimacy of financial instruments for addressing climate change. Section two opens with a discussion of the available literature with respect to the deployment of RBF instruments both in general and in relation to REDD+, after which, section three elaborates the methodological approach of this paper. The subsequent sections describe the discourses of both recipient and donor countries with respect to their adherence to the Amazon Fund (section four) as well as the internal contradictions that emerge in recent years (section five). The paper concludes with some considerations for understanding RBF instruments.

2 Results-based funding and REDD+

Much literature has discussed the relevance of RBF in education and healthcare policies (Broom 1995; Low-Beer et al. 2007; Meessen et al. 2011) as well as environmental governance (e.g., Angelsen 2017; Norman and Nakhooda 2014). This literature has produced a very diverse terminology, including “results-based funding,” “payments-for-performance (P4P),” “performance-based aid,” and many others (Angelsen 2017; Eldridge and Palmer 2009; Müller et al. 2013; Oxman and Fretheim 2008). Eichler (2006, p. 5) defines RBF more generically as the “transfer of money or material goods conditional upon taking a measurable action or achieving a predetermined performance target.” This definition denotes that payments are conditional on the demonstration of results through quantitative performance indicators (Müller et al. 2013; Turnhout et al. 2014). Moreover, it reflects the argument that RBF directly addresses the “principal-agent problem” in which one actor (i.e., “principal”) seeks behavioral change or provision of specific services from another actor (i.e., “agent”) (Eichler 2006; Eldridge and Palmer 2009). These characteristics evoke optimism among some scholars about “the potential of performance-based financing to reform” (Meessen et al. 2011, p. 153). As such, RBF is reminiscent of ideas related to New Public Management (NPM), which emphasizes a managerial approach to addressing policy issues and represents public administrations that are efficient, “lean and purposeful,” in contrast to public administrations that advocate orderliness as in bureaucracies (Gruening 2001).

Another strand of literature has adopted a more critical stance towards the potential of RBF. Although RBF did improve the uptake of preventive health services in low income countries, for example, Oxman and Fretheim (2009) expressed their concerns about the long-term sustainability of desired effects (e.g., contracting out), the occurrence of undesirable effects like cherry-picking (e.g., excluding care for “difficult” patients) and unintended behaviors (e.g., perpetuating child malnourishment to retain benefits), and the general effectiveness in addressing complex and broad problems. In addition, Eldridge and Palmer (2009, p. 163) observed that, for some health models, “there was variation in whether payment was made for outcomes or for process indicators” and warned that confusing performance indicators like immunization rates as targets may actually yield adverse effects on effectivity. Furthermore, similar critiques have appeared in NPM literature, particularly with respect to its paradigmatic nature. Hood and Peters (2004, p. 271), for example, identified the unintended effect of “goal displacement” where performance indicators “remained largely processual and compliance-oriented, in spite of the all-pervasive rhetoric of [results-oriented approaches]” (see also Lynn 1998). These observations suggest that many problems of RBF emanate from a lack of clear definitions and, consequently, a susceptibility to diverging interpretations.

The issues of unclear definitions and discursive diversity has also affected national and international REDD+ debates (Den Besten et al. 2014; Hiraldo and Tanner 2011; Somorin et al. 2012; Van der Hoff et al. 2015). Some scholars have already identified that REDD+ implementation does not necessarily require stakeholder alignment or discursive dominance, as much literature would suggest, but may involve a parallel materialization of distinct discourses (Turnhout et al. 2016; Van der Hoff et al. 2015). Still, this materialization implies an alignment of stakeholder interests between donor and recipient countries in order to solve the aforementioned principal-agent problem. This alignment involves the balancing of appropriate compensation (i.e., recipient risks), performance expectations (i.e., investor risks), and ownership of the results obtained (i.e., host vs donor country) (Müller et al. 2013; Zadek et al. 2010). In this respect, the establishment of the Amazon Fund in 2008 built on a desire of the Brazilian government to receive non-offset-based compensation for past deforestation reductions (Carvalho 2012) that coincided with the decision of the Norwegian government to increase its international climate mitigation efforts and thus becoming a leading player at the climate negotiations (Hermansen 2015; Hermansen et al. 2017). Some scholars, however, subject the RBF structure of the Amazon Fund to critical scrutiny. Angelsen (2017, p. 258), for example, questions whether the ex-post agreements of the Amazon Fund are “results-based in practice because the marginal incentives [for further deforestation reductions] are not in place.” Other scholars argued that stakeholder interests may not be fully aligned yet, but the conflicts and contradictions are internally negotiated with relevant stakeholders rather than publicly criticized in the media (Hermansen et al. 2017).

The ongoing debate in the literature suggests that a closer look at clashing interpretations of results between donor and recipient organizations may be useful for understanding potential challenges of RBF operations. We define discourses as “ensembles of ideas, concepts and categories through which meaning is given to social and physical phenomena, and which are produced and reproduced through an identifiable set of practices” (Hajer and Versteeg 2005, p. 175). In an earlier article that applies this definition, we already identify the Amazon Fund as the central REDD+ institution of a “sustainable development discourse” of REDD+ in Brazil (Van der Hoff et al. 2015). Extending this argumentation, we argue that Brazilian organizations are not the only stakeholders that actively produce and reproduce this discourse through the practices of the Amazon Fund, since donor countries have made equal contributions to its materialization (Angelsen 2017; Hermansen 2015). As such, this research paper contributes to the literature above by describing the interpretations of recipient and donor countries with respect to RBF, especially emphasizing their understanding of “results” or “performance” upon which funding is based. Moreover, such analysis aims to understand the processes of stakeholder alignment in the bilateral agreements of the Amazon Fund and the discursive tensions that arise from them.

3 Research methodology

The primary data of this research paper entails thirteen semi-structured interviews conducted by the first and second author between 2012 and 2017. The criteria for interview selection include the representativeness of either recipient or donor country as well as close involvement in discussions on the development of the Amazon Fund. Interviewees related to the donor countries (i.e., Norway and Germany) include officials of Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative (NICFI), the Norwegian embassy in Brazil, the German Development Bank (KfW), and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). Officials of the recipient country (i.e., Brazil) include the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), the Steering Committee (COFA) and Technical Committee (CTFA) of the Amazon Fund, as well as the Brazilian Ministries of Foreign Affairs (MRE) and Finance (MF). These interviews were supplemented with auxiliary expert interviews with observing scholars and NGOs. The interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using simple coding methods that initially emphasized the distinct financial transaction processes that, after analysis, were regrouped to reflect the interviewees’ concerns related to contract criteria, disbursement strategy, and emerging contradictions. This research paper also relies on secondary data that support the statements from the interview analysis, including relevant legislative documents, the donation agreement, the Amazon Fund project document, the minutes of COFA meetings, annual reports, and website information (www.amazonfund.gov.br). Secondly, the empirical data was enriched and cross-checked with observations related to operations of the Amazon Fund, including onsite visits to Amazon Fund projects in the state of Mato Grosso, informal conversations with governmental officials, participation in a roundtable on the GIZ evaluation, and participation in meetings between recipient and donor countries. Finally, we circulated earlier versions of this article to key informants in order to check for inconsistencies of our findings and interpretations.

4 Brazil: result-based funding as a reward and support to national policies

Prior to the inception of the Amazon Fund in 2008, governmental organizations in Brazil were not favorable towards international forest governance debates and particularly opposed the possibility of including forests in offset-based mechanisms like the original REDD+ concept (Carvalho 2012). In the first half of the 2000s, a change in administration engendered favorable circumstances for the reconsideration of this opposition. The idea of receiving financial compensation for deforestation reductions strongly appealed to governmental organizations in Brazil, but particularly MRE argued that these payments should not engender future obligations nor offset domestic emissions of donor countries. The sharp reductions in deforestation that took place between 2004 and 2012 have been one of the main leverage points for a strong Brazilian position in the international climate negotiations. In this context, the original idea of “Compensated Reduction of Deforestation” developed into a REDD+ approach that revolved around a “sustainable development discourse” (see Van der Hoff et al. 2015), which in 2008 operationalized the international financial support for domestic forest policy instruments with the establishment of the Amazon Fund (see decree 6.527/2008). An NGO representative observed that “countries like Brazil (…) do not admit something mandatory, or something a little bit more commitment, [but] always voluntary [in part due to] a history of sovereignty [concerns].” As such, Brazil developed an understanding of RBF as reward for reducing deforestation already achieved rather than a contractual commitment to provide further reductions.

This understanding of RBF resonates in the rules establishing the Amazon Fund and related bilateral agreements with Norway. Firstly, the Amazon Fund performs an annual monetary valuation of emissions reductions (i.e., USD5/tCO2) based on the difference between the actual deforestation rate and a 10-year historical average (i.e., baseline) that changes every 5 years, which reflects the fundraising limit (BNDES 2018). Moreover, the minutes of the 16th COFA meeting (December 2014) indicated that MMA interpreted these annual calculations of the fundraising limit as cumulative, suggesting that the results between 2008 and 2016 allowed the Amazon Fund to receive a total amount of USD 21 billion according to CTFA calculations. Secondly, the Memorandum of Understanding as well as the donation agreements between Brazil and Norway repetitively employed the words “donation” and “contribution” for defining the nature of payment. This implies that the transfers of financial resources were permanent and do not require restitution in case of a reversal in deforestation trends. Finally, the decree establishing the Amazon Fund explicitly stated that the diplomas, which validate the payments and their correspondent emissions reductions, “are nominal, non-transferable, and do not generate rights or credits of any kind” (decree 6.527/2008, art. 2–2). This underscores the abstinence from offset-based transactions while still formally indicating the emissions reductions for which donor countries make their contributions.

The sovereignty concerns of Brazil can also be found in the structure of the Amazon Fund, albeit with some concessions. The nomination of the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), rather than the World Bank, as managing organization for the Amazon Fund stemmed from Brazilian demands for sovereign autonomy over the financial resources and institutional capacity for managing projects (Hermansen et al. 2017). At the same time, Brazilian legislation limits the use of donated financial resources to “preventing, monitoring and combating deforestation and promoting the conservation and sustainable use of the Amazon biome” (decree 6.527/2008, art. 1). While offset-based REDD+ projects would involve contractual emissions reduction targets in relation to business-as-usual emission projections (Rajão and Marcolino 2016), project approval is based on their support to national policies for attaining (sub)national emissions reduction targets. The Amazon Fund Guidelines and Criteria for Resource Allocation determine that projects’ need to demonstrate, for example, “coherence with the national and state Action Plans for the Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Legal Amazon – PPCDAM – (B5), which is an operational plan that aims to enhance monitoring and control, promote sustainable production activities and improve land title regulation. PPCDAM contributes to the attainment of Brazil’s nationally determined contribution (NDC), which proposed to ‘reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 37% below 2005 levels in 2025’. These observations indicate that the Amazon Fund is embedded within a broader political structure that aims to reduce emissions. According to a Brazilian diplomat, “one of the reasons that REDD+ cannot be offset is because calculating how much of the emission reduction is the result of national policies and how much is not, is something impossible and incomparable.”

Understanding the performance of the Amazon Fund in terms of its contribution to national policies for reducing carbon emissions has an important role in ensuring autonomy of resource allocation. The breadth of the actions covered by PPCDAM allows projects’ substantial flexibility to conform to the eligibility criteria of the Amazon Fund without necessarily proving how specific projects may induce deforestation and emission reductions. For instance, COFA decided in April 2014 (15th meeting) that the fund should give priority to “structuring” projects, which in practice involved a particular focus on implementing the Rural Environmental Registry (CAR). CAR is an instrument of the new Forest Code that enhances landowner visibility, and thereby enforcement capacity, by providing land use information of all private properties across Brazil. As a consequence, around 60% of financial resources of the fund have been allocated to CAR projects (18th COFA meeting, August 2015). Concurrently, some studies have demonstrated that before 2015, CAR has not been systematically used for law enforcement and has not led to deforestation reductions (Azevedo et al. 2014; Rajão et al. 2012). Therefore, the ongoing support for the implementation of CAR stemmed from a “faith that it is going to function” in the future and not by proven results, as noted by a member from COFA. These observations suggest that project performance indicators reflect their contribution to national forest policies (e.g., number of CAR registries) rather than achieved emissions reductions or obligations to do so.

5 Donor countries: results-based funding for future climate mitigation

Norway and Germany, represented by NICFI and by KfW and GIZ, respectively, share a common interest in donating to the Amazon Fund for a number of reasons. Firstly, these organizations have a long history in development aid that is continued with their involvement in the Amazon Fund. During the 1990s and early 2000s, Germany led a group of countries that supported the Pilot Programme for the Conservation of Brazilian Rainforests (PPG7). As PPG7 came to a close, Germany saw in the Amazon Fund the opportunity to continue and scale up their support to forest conservation initiatives. In this regard, a GIZ official argued that “now it was time […] to really have a policy active in the whole of the Amazon, no longer by means of a pilot programme.” In Norway, development aid was given a boost after socioenvironmental NGOs successfully placed forests on the political agenda, particularly emphasizing the cost-effectiveness of investing in deforestation reduction in tropical countries rather than domestic action as an important factor (Hermansen 2015). A few years later, a press release by the Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment (2015) quoted the statement by minister Sundtoft that “extending the [NICFI] initiative is the best contribution Norway can provide to a good agreement [during COP21] in Paris.” While the donations to the Amazon Fund cannot involve formal offsets due to Brazil’s resistance and have no link to the country’s NDC, some scholars have argued that the support from Norway, while formally still development aid, denotes a “political offset” for domestic emissions (Angelsen 2017; Hermansen et al. 2017). As such, the donations of financial resources to the Amazon Fund are aimed at incentivizing future emission reductions from deforestation and forest degradation, thereby representing a contribution to tackling climate change.

While the donors saw the Amazon Fund as part of their climate mitigation strategy, they also understood and abided to rules of the fund and the related Brazilian understanding of RBF. Donors recognized that the payments are made in reference to emission reductions from deforestation already achieved by Brazil in the past and accepted that Brazil is not obliged to demonstrate how Amazon Fund projects contribute to additional reductions. A KfW official asserted that “it was not imposed on [BNDES] to deliver these numbers, because (…) what [KfW] pays for was already obtained.” Instead, donor countries acknowledged and rewarded the historical achievements of Brazil as reflected in the calculations of the fundraising limit (see Section 4). An official of the Norwegian embassy explained that:

It is very hard to prove in a scientific way that this partnership has produced those results, but that is not the point. The point is that the results are coming in and Norway wants to support those results by recognizing results-based efforts and contributing with financial support to Brazil. And we believe that Brazil will continue to reduce deforestation, and that is the main basis of the desire to want to continue the partnership.

At the same time, donor countries still assured their contribution to incentivizing further emission reductions as the allocation of financial resources by BNDES is conditional upon reinvestment in projects that contribute to further achievements (see Section 4). In this respect, as a NICFI official illustrated, the “hands-off” approach to their contract with BNDES stemmed from a confidence that BNDES “cannot spend it on the army [or] build a public park in Rio de Janeiro.”

Donor countries also agreed with Brazil on the importance of “structuring” projects that add to ongoing governmental policies, rather than isolated initiatives. An official of the Norwegian embassy, for example, argued that “you cannot [reduce deforestation] with projects [alone], the government needs to change its policy and incentive structures.” Extending this argument, a GIZ official claimed that “the Amazon Fund is a very important instrument for (…) consolidating Brazilian environmental policies.” In addition, this GIZ official added that, from a perspective of providing technical support, “Brazil is an anchor country [since] they already have the knowledge and economic power that allows for bilateral technical cooperation with Germany.” As such, donor organizations highly valued the competence of BNDES as assurance that the financial resources will be adequately employed for achieving further deforestation reductions. A KfW official concluded that donating to the Amazon Fund is “kind of a safe bet, because there was diminished deforestation and (…) the method of calculation was conservative.” Moreover, donor countries intended to provide financial support for institutional changes that adequately address deforestation. In this respect, for example, NICFI officials have reaffirmed that “CAR is an important instrument for supporting public policy in Brazil and supporting one of the most important tools they have for reducing deforestation, which is monitoring and control.” These intensions made it acceptable for donor organizations to evaluate the performance of the Amazon Fund on the basis of their support to national policy implementation rather than performance indicators that reflect project-level emissions reductions (e.g., Anache et al. 2016).

6 Clashing conceptualizations of result-based funding

Although the interpretations of Brazilian and donor organizations agreed on many features of the Amazon Fund, there were some indications of diverging views between the two sides. Initial clashing conceptualizations arose with respect to spending the financial resources from donations. Donor organizations complained that by December 2012, the fund had only approved 36 projects and disbursed USD 55 million, less than half of the amount donated (see Fig. 1). Part of the reason involved the demanding guidelines and criteria for the approval of project proposals, for which BNDES requires the availability of financial resources for the entire project lifespan. In addition, NICFI was still following transfer procedures that demanded “an immediate, demonstrated and planned need” for financial resources from BNDES. Consequently, donor countries transferred USD 116 million in only five donations (BNDES 2018), after which they started pressing BNDES to accelerate the very project approval procedures that they appreciated as sign of competence. The issue was resolved by efforts on both sides. As the number of project proposals to the Amazon Fund grew in subsequent years, donor countries were able to make up for the delay and transferred USD 654 million in 2013 (see Fig. 1). At the same time, NICFI operationalized changes in transfer procedures for all projects (not just Brazilian) in 2013 that liberated payments upon demonstration of emissions reductions, which were now in line with “annualized” budget approval procedures.

Donations, disbursements, and deforestation rates per year. Source BNDES 2017; PRODES/INPE http://www.obt.inpe.br/prodes/prodes_1988_2016n.htm

It was following the establishment of this new procedure to transfer annual payments based on results rather than needs that revealed the existence of clashing interpretations of the temporal aspect of results in the Amazon Fund. As mentioned above, the Amazon Fund accumulated the monetary values of annual results since 2006. However, both donor countries signaled that they are unwilling to make financial payments based on achievements too far in the past, especially if deforestation rates continue to rise. A KfW official, for example, articulated this concern quite clearly:

For sure a donor would not want to pay for an achievement which is like ten years back. (…) The huge gains in 2004 to 2010, we would not want to pay for that. [Therefore], if you ask me how the Amazon Fund is doing, it is more like how they use the money they get to produce more results [in the future].

While BNDES accumulated the monetary values of annual results since 2006 (see Section 4), KfW’s donation history shows that transactions made so far related to emissions reductions from 2009 onwards. This trend was most clearly observed in the transaction patterns of Norway. Since 2013, its payments have been exclusively based on emission reductions achieved in the preceding year (BNDES 2017; Norway 2018). Moreover, NICFI officials have presented this rule as a guiding principle for its budget approval of donations to the Amazon Fund since the start. Only transactions from Petrobras, a national oil company donating to the Amazon Fund, have consistently related to results in 2006. These observations directly contradict the interpretation of the Brazilian government that the fundraising limit of the Amazon Fund is a cumulative monetary valuation of emission reductions of which only 10% has been received (see Section 4). Officials from the two donor countries did not question Brazil’s attempt to obtain payments based on the accumulated results via other sources, such as the GCF. However, the unwillingness of Norway and Germany to reward those results make it very unlikely that the fundraising limit may be met.

The clashing interpretations on the temporal aspects of results have very practical consequences for future donations as the calculative basis for fundraising limits (i.e., the difference between actual deforestation rates and the reference level) is declining. For instance, while the reference level for achievements from 2011 to 2015 was still built on the average deforestation rate between 2001 and 2010, and therefore included the substantial reductions of those years, the new reference level builds on the average deforestation rate between 2006 and 2015, thereby excluding some of these achievements. As deforestation rates have increased 7464 km2 in 2009 (year of first disbursements) to an estimated 7893 km2 in 2016, the monetary value of deforestation reductions dropped from USD 2.5 billion in 2015 to USD 41 million in 2017 (BNDES 2018). This situation suggests that donations may dry up over time if results continue to wane, despite the accumulation of results in previous years.

A second clashing conceptualization emerged with respect to the epistemological approach to the attainment of valid knowledge on the results of projects supported by the Amazon Fund. While the calculation of the fundraising limit (i.e., emissions reductions) has not been challenged, some governmental bodies within the donor countries started to be concerned with the disconnect between these calculations and the basis for financial resource distribution (i.e., policy alignment). On the one hand, the donation agreement between Brazil and Norway in 2013 stated that the disbursements of contributions “shall be […] based on fulfillment of the reporting requirements” (art. VI-3), including the submission of “reports and documentation assessing the contribution of the Fund in reducing emission from deforestation and forest degradation” (art. VIII-1). On the other hand, donor countries did not acknowledge that this information has been provided. A KfW official, for example, argued that “there is not yet a monitoring process in place to get to the numbers of how much deforestation was avoided by these projects.” Similarly, a GIZ official articulated that “the Amazon Fund begins as a REDD+ [mechanism] for receiving resources but does not [apply] REDD+ for distribution.” These sentiments seem to have instigated discursive conflicts and pressure to improve the functioning of the Amazon Fund. Norwegian officials also articulated their concerns during a high-level meeting held in March 2015, where BNDES, donor organizations, officials of the Brazilian government, NGOs, and researchers came together to discuss the “evolution, challenges and perspectives” of the Amazon Fund. While recognizing the autonomy of BNDES in managing the fund, Norwegian and German officials demanded for the first time a “stronger strategy focus” and the need to “review the priorities of the Amazon Fund.” One senior official from Norway articulated the concern that “the problem [of evaluating performance] is not to be solved with […] more information at project level,” thereby hinting at the lack of information on aggregate contributions of the Amazon Fund to bringing down deforestation.

In spite of differing interests in and approaches to evaluating the performance of the Amazon Fund (see Section 5), both donor countries agree on the importance of improving performance indicators. The Real-Time Evaluation of NICFI in 2014, for example, pointed out that BNDES did not comply with a provision in the donation agreement (art. 8.1) that requires the bank to publish “reports and documentation assessing the contribution of the fund in reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation”, even though the same report also acknowledges that this non-compliance is “not seen as a major concern for either party” (LTS International 2014, p. 224). Correspondingly, the Norwegian Office of the Auditor General has published a report in May 2018 that also pointed to the need to improve the performance evaluation of projects funded by NICFI (Riksrevisjonens 2018).

The concern with evaluation has been gradually materializing in Brazil. In 2016, GIZ and BNDES published an evaluation report that assessed the performance of an Amazon Fund project in relation to its objectives, but only one of the 44 guiding questions of its conceptual framework addressed the extent to which “the project has contributed or may come to contribute directly or indirectly to the reduction of emissions from deforestation or forest degradation” (Anache et al. 2016, p. 71). This evaluation was followed by several other project evaluations conducted by GIZ and KfW, all of which addressed this question to some extent, thereby suggesting an increasing concern with the Amazon Fund’s contribution to reducing emissions. At the same time, these evaluations still admitted indirect contributions to emissions reductions and applied mostly qualitative performance criteria. Finally, German officials have reported new evaluation efforts by the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America (CEPAL) since 2018. It remains unclear, however, whether these evaluations will answer the concerns from donor countries about the fund’s contribution to emission reductions, especially in a context of rising deforestation rates.

7 Discussion and conclusion

Our analysis shows that both recipient and donor countries have retained a general interpretation of the Amazon Fund as a promising and well-functioning mechanism for incentivizing deforestation reductions. While there has been some conflict in initial years, these have been quickly resolved as the Amazon Fund evolved. Concurrently, the failure to sustain Brazil’s downward deforestation trend after 2013 (see Fig. 1) revealed a clashing interpretation of RBF in two fundamental ways. Firstly, interpretations have diverged about the temporal emphasis of the results for which financial resources were mobilized. Brazilian officials strongly argued that all results obtained since 2006 have merited a financial reward as those reductions have already benefited the planet. Although donor countries have agreed that such results should form the basis for payments, they are more concerned with the attainment of future results and have therefore made provisions to warrant the direct effectiveness of their donations. This is best reflected in Norwegian budget approval and (since 2013) financial transaction procedures that are exclusively based on results achieved in the preceding year, which safeguard incentivizes for the Brazilian government to generate further results. In this respect, donor countries have indicated that it is increasingly unlikely that the huge results obtained by Brazil between 2006 and 2013 will be translated into RBF payments in the future.

A second manifestation of clashing interpretations concerns the measurement of results in a valid way. For the Brazilian government, it is sufficient to measure the past results of emission reductions at biome in relation to a historical baseline, as defined by the Amazon Fund original agreement. In their view, the investments from Amazon Fund projects do not need to demonstrate the ability to provide additional reductions as long as the approved projects are in line with the guidelines of deforestation reduction policies. This view was challenged as donor countries have increasingly scrutinized the Amazon Fund in an attempt to substantiate the additional results generated by its supported projects. They found that the challenges to measuring the impact of indirect contributions to deforestation reductions (i.e., structural changes in the regional development model as well as increased institutional capacity) may be insurmountable. In addition, an emphasis on performance indicators that more adequately reflect additional deforestation reductions from Amazon Fund projects may prevent such structuring projects from meeting the eligibility criteria for financial support. Following Turnhout et al. (2014), an insistence on performance indicators that reflect the direct impact of the Amazon Fund on emissions reductions reflects an impoverished foundation for disbursing financial resources, because it risks the underappreciation of the full complexity of deforestation dynamics in the Amazon. RBF approaches that emphasize carbon emissions, such as the original REDD+ concept, have been subject to severe criticism for their misrepresentation of local realities in policy-making as well as knowledge production (Rajão 2013; Wilson 2013). Nevertheless, these demands for demonstrating the results of the Amazon Fund in scientifically rigorous manner are likely to become an important topic for donor countries. This is also true for the scientific community and NGOs who have so far kept their criticisms largely behind closed doors (Hermansen et al. 2017). One may therefore expect that a return to the discussion on what ultimately constitutes good governance for addressing environmental issues (see Hood and Peters 2004; Lynn 1998).

The issues currently facing the Amazon Fund could also migrate to UNFCCC debates, especially on the definition on how the Green Climate Fund will operate and make RBF payments. A renegotiation of the basic principles of RBF, as currently expressed in the Warsaw Framework for REDD+, is still unlikely (Müller et al. 2013; Voigt and Ferreira 2015). At the same time, “tying payment to quantified results would enable funders to take a more hands-off approach to determining how funds are used,” which appears to be increasingly conditional on the ability to demonstrate the effectiveness of RBF activities (Müller et al. 2013, p. 4). In this context, two scenarios are more likely to occur. In the first scenario, donor and recipient countries may still consider bilateral agreements that build on the RBF model defined by the Warsaw Framework for REDD+, but include requirements for measuring results generated by the new investments in addition to the existing demonstration of past results. For instance, this could involve measuring emission reductions at project level without issuing or transferring offsets. In the second scenario, countries may slowly abandon the RBF model and invest instead in the potential new mechanisms that are currently under negotiation in international environmental governance debates. These include, most notably, the internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMOs) under Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement.

Notwithstanding the modality of forest finance, it has become clear that performance indicators continue to be a critical but controversial issue in both scientific literature and political debates on RBF. More specifically, an important question for scientific research is whether and on what grounds alternative RBF instruments containing a more direct relation between the project performance and their impact on central objectives, such as the (contractual) emissions reduction obligations that are characteristic of offset markets, become considered as substitutes for aid-based RBF instruments, especially when the latter fails to meet stakeholder expectations. The Amazon Fund must be considered as a unique and important experience in many ways, most notably its longstanding history, volume of donations and its support to numerous projects. As such, it has many lessons for the implementation and operationalization of RBF not only in Brazil but also in and between other countries that aim to undertake similar efforts. As political debates still struggle to find the most adequate approach to financing deforestation reduction, we believe that the considerations presented in this paper are a necessary first step towards the improvement of financial instruments for addressing climate change.

References

Anache B, Toni F, Maia HT, Queiroz J (2016) Effectiveness evaluation report: Amazon’s water springs project. Retrieved from http://www.amazonfund.gov.br/en/monitoramento-e-avaliacao/independent-evaluations/

Angelsen A (2017) REDD+ as result-based aid: general lessons and bilateral agreements of Norway. Rev Dev Econ 21(2):237–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12271

Azevedo A, Rajão R, Costa M, Stabile M, Alencar A, Moutinho P (2014) Cadastro Ambiental Rural e sua influência na dinâmica do desmatamento na Amazônia Legal. In: Boletim Amazônia em Pauta N. 3. IPAM, Brasília

BNDES (2017) Amazon fund activity report 2016. Retrieved from Rio de Janeiro

BNDES (2018) Amazon fund activity report 2017. Retrieved from Rio de Janeiro

Brockhaus M, Korhonen-Kurki K, Sehring J, Di Gregorio M (2015) Policy progress with REDD+ and the promise of performance-based payments: a qualitative comparative analysis of 13 countries. Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Bogor

Broom CA (1995) Performance-based government models: building a track record. Public Budg Finance 15(4):3–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5850.01050

Carvalho FV d (2012) The Brazilian position on forests and climate change from 1997 to 2012: from veto to proposition. Rev Bras Polit Int 55:144–169

Den Besten JW, Arts B, Verkooijen P (2014) The evolution of REDD+: an analysis of discursive-institutional dynamics. Environ Sci Pol 35:40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2013.03.009

Eichler R (2006) Can “pay-for-performance” increase utilization by the poor and improve the quality of health services? Discussion paper for the first meeting of the working group on performance-based incentives. Center for Global Development, Washington

Eldridge C, Palmer N (2009) Performance-based payment: some reflections on the discourse, evidence and unanswered questions. Health Policy Plan 24(3):160–166. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czp002

Gruening G (2001) Origin and theoretical basis of new public management. Int Public Manag J 4(1):1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7494(01)00041-1

Hajer M, Versteeg W (2005) A decade of discourse analysis of environmental politics: achievements, challenges, perspectives. J Environ Policy Plan 7(3):175–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080500339646

Hermansen E (2015) I will write a letter and change the world: the knowledge base kick-starting Norway’s rainforest initiative. Nordic J Sci Techno Stud 3(2):34–46

Hermansen E, McNeill D, Kasa S, Rajão R (2017) Co-operation or co-optation? NGOs’ roles in Norway’s international climate and forest initiative. Forests 8(3):64

Hiraldo R, Tanner T (2011) Forest voices: competing narratives over REDD+. IDS Bull 42(3):42–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2011.00221.x

Hood C, Peters G (2004) The middle aging of new public management: into the age of paradox? J Public Adm Res Theory 14(3):267–282. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muh019

Low-Beer D, Afkhami H, Komatsu R, Banati P, Sempala M, Katz I, Schwartländer B (2007) Making performance-based funding work for health. PLoS Med 4(8):e219. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040219

LTS International (2014) Real-time evaluation of Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative: synthesizing report 2007–2013. Retrieved from https://www.norad.no/en/toolspublications/publications/2014/real-time-evaluation-of-norways-international-climate-and-forest-initiative.-synthesising-report-2007-2013/

Lynn LE (1998) A critical analysis of the new public management. Int Public Manag J 1(1):107–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7494(99)80087-7

Meessen B, Soucat A, Sekabaraga C (2011) Performance-based financing: just a donor fad or a catalyst towards comprehensive health-care reform? Bull World Health Organ 89:153–156

Müller B, Fankhauser S, Forstater M (2013) Quantity performance payment by results: operationalizing enhanced direct access for mitigation at the green climate fund. Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, Oxford

Norman M, Nakhooda S (2014) The state of REDD+ finance. CGD Working Paper 378

Norway (2018) Brazil - Ministry of Climate and Environment. Retrieved from https://www.regjeringen.no/en/topics/climate-and-environment/climate/climate-and-forest-initiative/kos-innsikt/brazil-and-the-amazon-fund/id734166/

Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment (2015) Norwegian International Climate and Forest Initiative Extended until 2030. Retrieved from https://www.regjeringen.no/en/aktuelt/norwegian-international-climate-and-forest-initiative-extended-until-2030/id2467031/

Oxman AD, Fretheim A (2008) An overview of research on the effects of results-based financing (8281212098). Retrieved from Oslo:

Oxman AD, Fretheim A (2009) Can paying for results help to achieve the millennium development goals? Overview of the effectiveness of results-based financing. J Evid Based Med 2(2):70–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-5391.2009.01020.x

Rajão R (2013) Representations and discourses: the role of local accounts and remote sensing in the formulation of Amazonia’s environmental policy. Environ Sci Pol 30(0):60–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.07.019

Rajão R, Azevedo A, Stabile MCC (2012) Institutional subversion and deforestation: learning lessons from the system for the environmental licensing of rural properties in Mato Grosso. Public Adm Dev 32(1):229–244

Rajão R, Marcolino C (2016) Between Indians and “cowboys”: the role of ICT in the management of contradictory self-images and the production of carbon credits in the Brazilian Amazon. J Inf Technol 31(4):347–357

Riksrevisjonens (2018) Riksrevisjonens undersøkelse av Norges internasjonale klima- og skogsatsing. Oslo: Dokument 10(2017–2018):3

Somorin OA, Brown HCP, Visseren-Hamakers IJ, Sonwa DJ, Arts B, Nkem J (2012) The Congo Basin forests in a changing climate: policy discourses on adaptation and mitigation (REDD+). Glob Environ Chang 22(1):288–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.08.001

Streck C, Howard A, Rajão R (2017) Options for enhancing REDD+ collaboration in the context of article 6 of the Paris Agreement. Meridian Institute, Washington, DC

Turnhout E, Gupta A, Weatherley-Singh J, Vijge MJ, de Koning J, Visseren-Hamakers IJ, Lederer M (2016) Envisioning REDD+ in a post-Paris era: between evolving expectations and current practice. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.425

Turnhout E, Neves K, Lijster E d (2014) ‘Measurementality’ in biodiversity governance: knowledge, transparency, and the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services (Ipbes). Environ Plan A 46(3):581–597. https://doi.org/10.1068/a4629

Van der Hoff R, Rajão R, Leroy P, Boezeman D (2015) The parallel materialization of REDD+ implementation discourses in Brazil. Forest Policy Econ 55(0):37–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2015.03.005

Voigt C, Ferreira F (2015) The Warsaw Framework for REDD+: implications for national implementation and access to results-based finance. Carbon Clim Law Rev 9(2):113–129

Wilson M (2013) The dangerous path of nature commoditization. Consilience: J Sustain Dev 10(1):85–98

Zadek S, Forstater M, Polacow F (2010) The Amazon Fund: radical simplicity and bold ambition - insights for building national institutions for low carbon. Development Retrieved from http://www.zadek.net/amazon-fund/

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Minas Gerais State Research Foundation (FAPEMIG), the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) and IPAM/NORAD for the financial support provided for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

van der Hoff, R., Rajão, R. & Leroy, P. Clashing interpretations of REDD+ “results” in the Amazon Fund. Climatic Change 150, 433–445 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2288-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2288-x