Abstract

Background

Anxiety disorders are among the most common mental health problems in youth, and faulty interpretation bias has been positively linked to anxiety severity, even within anxiety-disordered youth. Quick, reliable assessment of interpretation bias may be useful in identifying youth with certain types of anxiety or assessing changes on cognitive bias during intervention.

Objective

This study examined the factor structure, reliability, and validity of the Self-report of Ambiguous Social Situations for Youth (SASSY) scale, a self-report measure developed to assess interpretation bias in youth.

Methods

Participants (N = 488, age 7–17) met diagnostic criteria for social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and/or separation anxiety disorder. An exploratory factor analysis was performed on baseline data from youth participating in a large randomized clinical trial.

Results

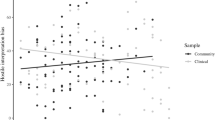

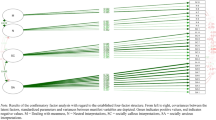

Exploratory factor analysis yielded two factors (accusation/blame, social rejection). The SASSY full scale and social rejection factor demonstrated adequate internal consistency, convergent validity with social anxiety, and discriminant validity as evidenced by non-significant correlations with measures of non-social anxiety. Further, the SASSY social rejection factor accurately distinguished children and adolescents with social phobia from those with other anxiety disorders, supporting its criterion validity, and revealed sensitivity to changes with treatment. Given the relevance to youth with social phobia, pre- and post-intervention data were examined for youth social phobia to test sensitivity to treatment effects; results suggested that SASSY scores reduced for treatment responders.

Conclusions

Findings suggest the potential utility of the SASSY social rejection factor as a quick, reliable, and efficient way of assessing interpretation bias in anxious youth, particularly as related to social concerns, in research and clinical settings.

ClinicalTrials.gov Number NCT00052078.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

25 July 2018

The original version of this article unfortunately contains the following errors. This has been corrected with this erratum.

Notes

To reduce subjectivity of the factor names, we showed the two groups of items to five child psychologists and psychiatrists and asked them what they would name each factor. For Factor 1 (Accusation/Blame), we got responses such as “Fear of punishment” or “Negative Attributions” or “Blame.” All of these responses are consistent with our naming. Similarly, for Factor 2 (Social Rejection), each expert stated either “social rejection” or “peer rejection.”

References

Aschenbrand, S. G., & Kendall, P. C. (2012). The effect of perceived child anxiety status on parental latency to intervene with anxious and nonanxious youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(2), 232.

Barrett, P. M., Fox, T., & Farrell, L. J. (2005). Parent—Child interactions with anxious children and with their siblings: An observational study. Behaviour Change, 22(04), 220–235.

Barrett, P. M., Rapee, R. M., Dadds, M. M., & Ryan, S. M. (1996). Family enhancement of cognitive style in anxious and aggressive children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 24, 187–199.

Beesdo, K., Knappe, S., & Pine, D. S. (2009). Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: Developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 32, 483–524.

Bögels, S. M., van Dongen, L., & Muris, P. (2003). Family influences on dysfunctional thinking in anxious children. Infant and Child Development, 12, 243–252.

Buckner, J. D., Schmidt, N. B., Lang, A. R., Small, J. W., Schlauch, R. C., & Lewinsohn, P. M. (2008). Specificity of social anxiety disorder as a risk factor for alcohol and cannabis dependence. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 42(3), 230–239.

Cannon, M. F., & Weems, C. F. (2010). Cognitive biases in childhood anxiety disorders: Do interpretive and judgment biases distinguish anxious youth from their non-anxious peers? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24, 751–758.

Chorpita, B. F., Albano, A. M., & Barlow, D. H. (1996). Cognitive processing in children: Relation to anxiety and family influences. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25(2), 170–176.

Compton, S. N., Peris, T. S., Almirall, D., Birmaher, B., Sherrill, J., & Albano, A. M. (2014). Predictors and moderators of treatment response in childhood anxiety disorders: Results from the CAMS trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82, 212–224.

Compton, S. N., Walkup, J. T., Albano, A. M., Piacentini, J. C., Birmaher, B., et al. (2010). Child/adolescent anxiety multimodal study (CAMS): Rationale, design, and methods. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 4, 1. http://www.capmh.com/content/4/1/1.

Costello, E. J., Egger, H. L., & Angold, A. (2005). 10-year research update review: The epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. Methods and public health burden. Journal of the American Academy Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 44, 972–986.

Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. W. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment Research and Evaluation, 10(7). http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=10&n=7.

Creswell, C., Murray, L., & Cooper, P. (2014). Interpretation and expectation in childhood anxiety disorders: Age effects and social specificity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(3), 453–465.

Creswell, C., & O’Connor, T. G. (2011). Interpretation bias and anxiety in childhood: Stability, specificity and longitudinal associations. Behavioural and Cognitive Therapy, 39, 191–204.

Creswell, C., Schniering, C., & Rapee, R. (2005). Threat interpretation in anxious children and their mothers: Comparison with nonclinical children and the effects of treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43, 1375–1381.

Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 74–101.

Daleiden, E. L., & Vasey, M. W. (1997). An information-processing perspective on childhood anxiety. Clinical Psychology Review, 17, 407–429.

Davis, W. B., Birmaher, B., Melhem, N. A., Axelson, D. A., Michaels, S. M., & Brent, D. A. (2006). Criterion validity of the mood and feelings questionnaire for depressive episodes in clinic and non-clinic subjects. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 927–934.

De Castro, B. O., Veerman, J. W., Koops, W., Bosch, J. D., & Monshouwer, H. J. (2002). Hostile attribution of intent and aggressive behavior: A meta-analysis. Child Development, 73(3), 916–934.

Dodge, K. A. (2006). Translational science in action: Hostile attributional style and the development of aggressive behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology, 18, 791–814.

Dodge, K. A., & Crick, N. R. (1990). Social information-processing bases of aggressive behavior in children. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 16(1), 8–22.

Fabrigar, L. R., Wegener, D. T., MacCallum, R. C., & Strahan, E. J. (1999). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 4(3), 272–299.

Field, Z. C., & Field, A. P. (2013). How trait anxiety, interpretation bias and memory affect acquired fear in children learning about new animals. Emotion, 13(3), 409.

Field, A. P., & Lester, K. J. (2010). Is there room for ‘development’ in developmental models of information processing biases to threat in children and adolescents? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 13, 315–332.

Graham, J. M. (2006). Congeneric and (essentially) tau-equivalent estimates of score reliability: What they are and how to use them. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66, 930–944.

Guy, W. (1976). The clinical global impression scale. The ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology-Revised. (DHEW, Publ No ADM 76-338), Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, Mental Health Administration, NIMH Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research, pp. 218–222.

Hadwin, J., Frost, S., French, C. C., & Richards, A. (1997). Cognitive processing and trait anxiety in typically developing children: Evidence for an interpretation bias. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 486–490.

Hadwin, J. A., Garner, M., & Perez-Olivas, G. (2006). The development of information processing biases in childhood anxiety: A review and exploration of its origins in parenting. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 876–894.

Hollingshead, A. B. (1957). Two factor index of social position. New Haven: Privately printed.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

In-Albon, T., Dubi, K., Rapee, R., & Schneider, S. (2009). Forced choice reaction time paradigm in children with separation anxiety disorder, social phobia, and nonanxious controls. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47, 1058–1065.

In-Albon, T., Klein, A., Rinck, M., Becker, E., & Schneider, S. (2008). Development and evaluation of a new paradigm for the assessment of anxiety disorder-specific interpretation bias using picture stimuli. Cognition and Emotion, 22, 422–436.

Kendall, P. C., Compton, S. N., Walkup, J. T., Birmaher, B., Albano, A. M., Sherrill, J., et al. (2010). Clinical characteristics of anxiety disordered youth. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24, 360–365.

Kendall, P. C., Hudson, J. L., Gosch, E., Flannery-Schroeder, E., & Suveg, C. (2008). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: A randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 282–297.

Kendall, P. C. (2012). Treating anxiety disorders in youth. In P. C. Kendall (Ed.), Child and adolescent therapy: Cognitive-behavioral procedures (4th ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Kent, L., Vostanis, P., & Feehan, C. (1997). Detection of major and minor depression in children and adolescents: Evaluation of the mood and feelings questionnaire. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 565–573.

Langley, A. L., Bergman, R. L., Barrett, P. & Piacentini, J. C. (2007). Ambiguous situations self-report for children and adolescents. Unpublished.

Lerner, J., Safren, S. A., Henin, A., Warman, M., Heimberg, R. G., & Kendall, P. C. (1999). Differentiating anxious and depressive self-statements in youth: Factor structure of the negative affect self-statement questionnaire among youth referred to an anxiety disorders clinic. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 28(1), 82–93.

Lester, K. J., Seal, K., Nightingale, Z. C., & Field, A. P. (2010). Are children’s own interpretations of ambiguous situations based on how they perceive their mothers have interpreted ambiguous situations for them in the past? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24, 102–108.

Lyneham, H. J., Abbott, M. J., & Rapee, R. M. (2007). Interrater reliability of the anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent version. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(6), 731–736.

March, J. S., Parker, J. D. A., Sullivan, K., Stallings, P., & Conners, C. (1997). The multidimensional anxiety scale for Children (MASC): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 554–565.

March, J. S., Sullivan, K., & Parker, J. (1999). Test–retest reliability of the multidimensional anxiety scale for children. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 13, 349–358.

Merikangas, K. R., He, J., Burstein, M., Swanson, S. A., Avenevoli, S., et al. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication-adolescent supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989.

Miers, A. C., Blöte, A. W., Bögels, S. M., & Westenberg, P. M. (2008). Interpretation bias and social anxiety in adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22(8), 1462–1471.

Muris, P., & Field, A. P. (2008). Distorted cognition and pathological anxiety in children and adolescents. Cognition and Emotion, 22, 395–421.

Muris, P., Kindt, M., Bögels, S., Merckelbach, H., Gadet, B., & Moulaert, V. (2000). Anxiety and threat perception abnormalities in normal children. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 22, 183–199.

Muris, P., Rapee, R., Meesters, C., Schouten, E., & Geers, M. (2003). Threat perception abnormalities in children: The role of anxiety disorders symptoms, chronic anxiety, and state anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 17, 271–287.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén.

Olason, D. T., Sighvatsson, M. B., & Smari, J. (2004). Psychometric properties of the multidimensional anxiety scale for children (MASC) among Icelandic school children. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 45, 429–436.

Pereira, A. I., Barros, L., Mendonça, D., & Muris, P. (2014). The relationships among parental anxiety, parenting, and children’s anxiety: The mediating effects of children’s cognitive vulnerabilities. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(2), 399–409.

Ronan, K. R., Kendall, P. C., & Rowe, M. (1994). Negative affectivity in children: Development and validation of a self-statement questionnaire. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 18, 509–528.

Rozenman, M., Amir, N., & Weersing, V. R. (2014). Performance-based interpretation bias in clinically anxious youths: Relationships with attention, anxiety, and negative cognition. Behavior Therapy, 45, 594–605.

Rynn, M. A., Barber, J. P., Khalid-Khan, S., Siqueland, L., Dembiski, M., McCarthy, K. S., et al. (2006). The psychometric properties of the MASC in a pediatric psychiatry sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 20, 139–157.

Sass, D. A., & Schmitt, T. A. (2010). A comparative investigation of rotation criteria within exploratory factor analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 45(1), 73–103.

Schniering, C. A., & Rapee, R. M. (2002). Development and validation of a measure of children’s automatic thoughts: The children’s automatic thoughts scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40, 1091–1109.

Silverman, W. K., & Albano, A. M. (1996). The anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV-child and parent versions. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

Stein, M. B., Fuetsch, M., Müller, N., Höfler, M., Lieb, R., & Wittchen, H. U. (2001). Social anxiety disorder and the risk of depression: A prospective community study of adolescents and young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58(3), 251–256.

Suarez, L., & Bell-Dolan, D. (2001). The relationship of child worry to cognitive biases: Threat interpretation and likelihood of event occurrence. Behavior Therapy, 32, 425–442.

Sund, A. M., Larsson, B., & Wichstrom, L. (2001). Depressive symptoms among young Norwegian adolescents as measured by the mood and feelings questionnaire (MFQ). European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 10, 222–229.

Tabachnik, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Vassilopoulos, S. P. (2006). Interpretation and judgmental biases in socially anxious and nonanxious individuals. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 34(02), 243–254.

Vassilopoulos, S. P., & Banerjee, R. (2012). Social anxiety and content specificity of interpretation and judgemental bias in children. Infant and Child Development, 21(3), 298–309.

Villalbø, M. A., Gere, M. K., Torgersen, S., March, J. S., & Kendall, P. C. (2012). Diagnostic efficiency of the child and parent versions of the multidimensional anxiety scale for children (MASC). Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 41, 75–85.

Waite, P., Codd, J., & Creswell, C. (2015). Interpretation of ambiguity: Differences between children and adolescents with and without an anxiety disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 188, 194–201.

Walkup, J. T., Albano, A. M., Piacentini, J., Birmaher, B., Compton, S. N., Sherrill, J. T., et al. (2008). Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. New England Journal of Medicine, 359(26), 2753–2766.

Weems, C. F., Costa, N. M., Watts, S. E., Taylor, L. K., & Cannon, M. F. (2007). Cognitive errors, anxiety sensitivity, and anxiety control beliefs: Their unique and specific associations with childhood anxiety symptoms. Behavior Modification, 31, 174–201.

Wergeland, G. J. H., Fjermestad, K. W., Marin, C. E., Bjelland, I., Haughland, B. S. M., Silverman, W. K., et al. (2016). Predictors of treatment outcome in an effectiveness trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for children with anxiety disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 76, 1–12.

Wood, A., Kroll, L., Moore, A., & Harrington, R. (1995). Properties of the mood and feelings questionnaire in adolescent psychiatric outpatients: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 36, 327–334.

Wood, J., Piacentini, J., Bergman, R. L., McCracken, J., & Barrios, V. (2002). Construct validity of the anxiety disorders section of the anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31, 335–342.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by funding by the National Institute of Mental Health (U01MH064089 to Dr. Walkup; U01MH64092 to Dr. Albano; U01MH64003 to Dr. Birmaher; U01MH63747 to Dr. Kendall, U01MH64088 to Dr. Piacentini; U01MH064003 to Dr. Compton, T32MH073517 to support Dr. Gonzalez, and T32MH017140 to support Dr. Rozenman) from the National Institute of Mental Health. Views expressed within this article represent those of the authors and are not intended to represent the position of NIMH, NIH, or DHHS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and it later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent (adults/legal caregivers) and assent (youth) were obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Appendix: SASSY Items

Appendix: SASSY Items

1. | You notice at school one day that a favorite book of yours is missing. Later you notice a boy/girl in your class has a similar book in their bag. What do you think is most likely to have happened to your book? | |

That child has stolen the book and put it in their bag | _____ | |

Someone who doesn’t like you has taken your book so you will be in trouble with your parents | _____ | |

You left your book at home | _____ | |

A friend borrowed the book thinking you wouldn’t mind | _____ | |

2. | You see the School Principal walking around the playground and s/he has been asking other children where you are. Why do you think the Principal is most likely looking for you? | |

The principal has a message for you | _____ | |

The principal thinks you have done something wrong and is angry | _____ | |

The principal wants to tell you he/she has noticed you are working harder and is pleased | _____ | |

One of the other children has told the teachers something bad about you | _____ | |

3. | You arrange to have a party at 4:00 pm and by 4:30 pm no one has arrived. What do you think is most likely to have happened? | |

Your friends are angry at you and don’t want to come | _____ | |

You must have put 4:30 pm on the invitation | _____ | |

Your friends are late because the traffic is very heavy | _____ | |

Your friends don’t want to come because they think it will be really boring | _____ | |

4. | You are showing your school project in front of the class and two students in the back are giggling. What is the reason that they are giggling? | |

They think the project is really dumb | _____ | |

They are being silly and tickling each other | _____ | |

Another kid is making funny faces at them | _____ | |

There is a big stain on your uniform and they are laughing at you | _____ | |

5. | You are sleeping over at a friend’s place and his/her parents seem to be really annoyed and cranky all the time. What is the most likely reason that your friend’s parents are annoyed and cranky all the time? | |

They had a little argument and are a bit upset with each other | _____ | |

They don’t really like you | _____ | |

They think you have done something wrong | _____ | |

They had a party last night and they are tired and don’t feel well | _____ | |

6. | You see a group of students from another class playing a great game. You walk over and want to join in and you hear them laughing. Which of the following do you think is most likely to happen next? | |

They are going to start looking at you and telling secrets about you | _____ | |

They will soon ask you to join in | _____ | |

One of them is likely to rush up and push you away | _____ | |

They are going to notice you and smile | _____ | |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gonzalez, A., Rozenman, M., Langley, A.K. et al. Social Interpretation Bias in Children and Adolescents with Anxiety Disorders: Psychometric Examination of the Self-report of Ambiguous Social Situations for Youth (SASSY) Scale. Child Youth Care Forum 46, 395–412 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-016-9381-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-016-9381-y