Abstract

Motivated by a large literature on how firm-specific resources (such as leadership and management skills, strategies, organizational capabilities and intellectual properties) drive firm performance, we propose and find that heterogeneity in investor optimism regarding firm-specific attributes plays a very important role in influencing the managerial propensity to manipulate financial statements. When firm-level investor optimism is moderate, the incidence of accounting misconduct increases, but it decreases when investors are highly optimistic. Further, market reaction to the announcement of financial restatements is more negative when investors held more optimistic firm-specific beliefs at the time of initial misstatement. These findings are robust to alternative firm-specific optimism measures linked to analysts, general investors and unsophisticated individual investors, controls for market-wide consumer sentiment unexplained by macroeconomic factors, economy-wide and industry-level optimism, potential selection bias and reverse causality. Our analysis highlights the importance of firm-level investor optimism in predicting, preventing and detecting accounting misconduct.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In this paper, we use “optimism” to refer to investor beliefs and sentiment because the upside is one of the main drivers of a rash of financial misconduct along business cycles (Ball 2009). Our test variables are continuous variables which captures both optimism and pessimism.

Povel et al. (2007) note “Thus, even if one defines “bad times” and “good times” in terms of the expected return to any given firm rather than the relative numbers of good and bad firms, our predictions still hold.” (p. 1337).

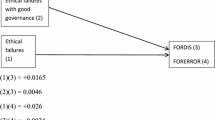

Although there is no strict definition or an exact threshold, a moderate level could be a one standard deviation around the mean. For example, results in Table 2 column (3) suggest that, based on the first-order condition, the predicted likelihood of irregularity peaks at firm-level Q is equal to 2.4. As the mean firm-level Q equals 1.97 and the standard deviation of firm-level Q equals 1.73, the peak of the predicted likelihood of irregularity falls within one-standard-deviation range from the mean firm-level Q. Calculations based on firm-level EPS suggest a similar pattern.

Wang et al. (2010) focus on IPO fraud and find a nonlinear relation between corporate fraud and investor prior beliefs about business conditions (also see and Wang 2011). We complement their work by showing that firm-level heterogeneity in optimism matters, even after controlling for industry-wide beliefs, in explaining the incidence of intentional accounting misstatements as well as shareholder wealth losses following the detection of questionable reports. Many studies focus on fraud detections, while our study focuses on fraud commissions. For example, Dechow et al. (2011) capture a set of characteristics of misstating firms (i.e., firms have already admitted “mistakes”). Similarly, Dyck et al. (2010) analyze whistleblowers’ incentives on the revelation of the fraud (i.e., fraud detections).

We examine accounting errors (unintentional misstatements defined in Hennes et al. 2008) while conducting falsification tests. To conserve space, results on errors are suppressed but are available upon request.

We are grateful to Jonathan M. Karpoff, Allison Koester, D. Scott Lee and Gerald S. Martin who generously shared with us the FSR database they used in their paper, Karpoff et al. (2017).

Karpoff et al. (2017) find that 87.5% of cases in GAO and 97.8% of cases in AA are non-misconduct cases, compared with 0% in FSR.

FSR and AA report the date when misstatements start while GAO does not. So we hand-collect the information on the year of commission if the case is unique in the GAO dataset.

In the irregularities sample, the median (mean) length from commission to detection is 2.64 (2) years and the upper (lower) quartile is 4 (1) years. In the errors sample, the median (mean) length from commission to detection is 2.17 (2) years and the upper (lower) quartile is 3 (1) years.

The GAO data on the classification of errors versus irregularities were generously provided by Professor Andrew J. Leone (http://sbaleone.bus.miami.edu/). Our classification of irregularities from the Audit Analytic (AA) data follows Badertscher et al. (2011). In the AA dataset, two variables help us distinguish irregularity from errors. One is “Res_fraud,” which equals 1 if the restatement identified financial fraud, irregularities and misrepresentations. The other is “Res_sec_investigation,” which equals 1 if the restatement disclosure identified that the SEC, PCAOB or other regulatory body is investigating the registrant (pp. 1494 of Hennes et al. 2008).

We delete firms with negative book value of equity and firms with the two-digit SIC code equal to 99 indicating shell holding companies and acquisition vehicles whose characteristics change dramatically after acquisition. Since our control sample is based on the population of COMPUSTAT firms for which data are available, we address the concern over matched sample problem raised by Jones et al. (2008) and Burns et al. (2010). As a large set of variables in regression analyses imposes further reduction in sample size, we provide a detailed description on sample construction in Panel B of “Appendix A.” The distributions of the commission and detection of irregularities over our sample period 1996–2012 and across industry groups are shown in Table B.1 in “Appendix B.”

Standard deviations for firm-level investor optimism are 1.173 for Firm Q and 1.464 Firm EPS Growth. Consistent with our expectation, these are much higher than the respective standard deviations for the industry-level optimism measures, 0.561 for Ind. Q and 0.168 for Ind. EPS Growth.

The estimated Pearson correlation coefficient between median Ind Q (Ind. EPS Growth) and Firm Q (Firm EPS Growth) is 0.24 (0.01), significant at 5% (see Table B.2 in “Appendix B”).

Williams (2012) points out that assessing the marginal effects of the squared terms is not meaningful because one cannot change a squared term without changing the variable itself. Therefore, it is impossible to explain the effect of the squared term in isolation of the variable itself.

We stress that all specifications in Table 2 control for annual return on assets (ROA) for the year preceding the beginning of accounting misstatements to control for (short-term) prior firm performance.

The bivariate probit model contains two separate equations, one for fraud commission and the other for detection of a fraud that was committed earlier. The probit model commonly used in prior studies focuses only on fraud detection; it is not capable of estimating the probability of fraud commission.

In unreported results, we construct excess firm-level Tobin’s Q and excess firm-level EPS Growth (both measured in excess of industry median). Further, we estimate firm-level buy-and-hold stock returns in excess of the industry median for 3 and 5 years prior to the occurrence of misstatements. The coefficient estimates for all these firm-level measures of investor beliefs are significant.

Consistent with this argument, Log Assets is negative and significant in the P(M) regression (− 0.079) in Table 3, suggesting that small firms are more susceptible to accounting misdeeds. But they are less likely to face intense investor monitoring, resulting in a significantly lower likelihood of detection of their accounting failures (0.115). Wang (2011) argues that new investment opportunities tend to decrease investors’ ability to detect misrepresentation of cash flows from existing assets, thus increasing a firm’s incentives to manipulate accounting reports. In line with this argument, we find a positive and highly significant coefficient on CAPX (0.905) in the misconduct regression and a significantly negative coefficient (− 1.205) in the detection regression. By contrast, investor protection laws enacted by SOX appear to have reduced the propensity for accounting misrepresentation (− 2.608) and increased the likelihood of disclosure of misconduct (6.007). When we examine firm-level proxies in Model (2) and both industry-level and firm-level proxies in Model (3), these control variables have comparable magnitude of size and statistical significance.

In unreported results, we include ST and LT compensation directly in the misconduct equation and find that the coefficient estimates of our test variables are still robust.

Panel regressions with firm-fixed effects further capture unobserved heterogeneity at the firm level. The GMM accounts for unobserved heterogeneity (i.e., unobservable variables affect both the dependent and independent variables) as well as simultaneity (i.e., independent variables are functions of the dependent variables). Dynamic GMM is so far one of the most powerful econometric tools to address the endogeneity of Tobin’s Q (Erickson and Whited 2012).

We calculate abnormal accruals as the error term for firm i in year t by regressing total accruals for firm i in year t on the inverse of total assets in year t − 1, changes in revenue in year t (scaled by total assets in year t − 1) minus changes in receivables in year t (scaled by total assets in year t − 1) and gross property, plant and equipment in year t (scaled by total assets in year t − 1). The modified Jones model is estimated for each Fama and French (1997) 48-industry and year group.

Furthermore, we use the Erickson and Whited (2012) estimator to address potential concerns about measurement error in firm-level Q with a within-firm transformation to account for firm-fixed effects and find that the coefficient estimates on firm-level Q are larger. For example, using the third-order estimator in Erickson and Whited (2012), the coefficient estimates of firm Q is 0.082 and that of firm Q squared is − 0.0032. These positive and significant coefficient for firm-level Q and negative and significant coefficient for firm-level Q squared (std. error of firm Q is 0.017 and std. error of firm Q squared is 0.0001, both with p values equal to 0.000) offer support for a causal relation between the incidence of accounting misconduct and firm-level investor optimism. Also, see Table B.5 in “Appendix B.”

In the first stage, firm-level EPS growth is regressed on earnings management with firm- and year-fixed effects. Residual Firm EPS Growth is calculated as actual firm-level EPS growth minus the predicted level of EPS growth. In the second stage, we estimate the previous bivariate probit model.

We are grateful to an anonymous referee for suggesting consumer sentiment as an alternative proxy for investor optimism. The term sentiment refers to “feelings or beliefs about a situation, state of affairs, or event” (Hribar et al. 2017, p. 26). Most of studies in finance and accounting focus on beliefs that are “unjustified” based on available information (e.g., Baker and Wurgler 2006; Lemmon and Portniaguina 2006). The focus of our study is firm-level investor optimism, which refers to investors’ belief about firm perspectives. It includes both “justified” and “unjustified” beliefs. Differentiating “unjustified” sentiment from “justified” part is beyond the scope of this paper. However, we believe the “unjustified” part is important in examining the roles of different players in the market. In the revised version, we apply a variety of measures to capture both aspects.

ICS (Fundamental) has an estimated Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.20 with median Ind Q and 0.40 with Ind. EPS Growth), both significant at 5%; ICS (Sentiment) has an estimated Pearson correlation coefficient of -0.02 with Firm Q (significant at 5%) and 0.00 with Firm EPS Growth (see Table B.2 in “Appendix B”).

We obtain essentially similar results if we use the mean of all four-quarters of the preceding year instead of consumer confidence estimates specific to the preceding fourth quarter. Results are similar when we cluster standard errors at only the firm level.

To verify the robustness of our basic results reported in Table 2, we add ICS and ICS Sq. to Panels A, B and C of Table 2. As shown in Table B.8 in “Appendix B,” the coefficient estimates on the three firm-specific investor optimism proxies—Firm Q, Firm EPS Growth and Prior Return 5 Yr., are all positive and significant and those on their squared values are all negative and significant, consistent with prediction in Hypothesis 1.

Overnight Return has an estimated Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.08 with Firm Q, − 0.02 with Firm EPS Growth and − 0.02 with ICS (Sentiment) (see Table B.2 in “Appendix B”). Due to large sample size, all these correlation coefficients are statistically significant.

We are grateful to an anonymous referee for suggesting analyst stock recommendations as alternative proxies for investor optimism.

Firm Analyst Recommendation has an estimated Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.14 with Firm Q, 0.02 with Firm EPS Growth, 0.07 with Overnight Return and 0.10 with ICS (Sentiment), all significant at 5% (see Table B.2 in “Appendix B”).

Because Firm Analyst Recommendation is essentially a categorical variable, we verify that our results are robust to using spline regressions based on quintiles, which allow the slope coefficient to vary with different levels of investor beliefs, see Table B.9 in “Appendix B,”

The reduction in sample size is due to missing return variables in CRSP.

Due to a smaller sample size as well as the nature of our sample which consists of only restating firms, the standard deviation of Firm EPS Growth_commit is higher than Firm EPS Growth used in Hypothesis 1 although both are constructed in the same way.

These findings are consistent with Bardos et al. (2011) who observe that investors see through initial materially manipulated earnings and push stock prices down months ahead of restatement announcement.

Although our treatment of IRR as exogenous is consistent with most prior studies on market reaction, the preceding analysis is subject to potential concerns about sample selection because the commission and disclosure of financial misconduct are strategic choices made by the firm, not random variables. For example, managers have greater incentives to manipulate accounting reports when investors are optimistic (as postulated by our first hypothesis) and disclose their misdeeds during periods of bleak economic outlook (to camouflage the bad news). To address these concerns, we return to propensity score matching analysis based on high investor optimism used in Table B.7. The results are summarized in Table B.11 in “Appendix B.” Consistent with our second hypothesis, the interaction coefficient estimates on High Firm Q_commit*IRR in Panel A and High Firm EPS Growth_commit*IRR in Panel B are both negative and significant at 5% or better.

The literature suggests that financial scandals come in waves because firms tend to misreport when they suspect their industry peers are pursuing similar accounting practices. In addition, the disclosure of financial misconduct could be strategic choices made by the firm. As an added scrutiny of potential selection problems, we conduct propensity score matching analyses based on ex ante restatement risk. Panel A (B) of Table B.12 in “Appendix B” above presents results based on prior investor optimism proxied by Tobin’s Q (EPS Growth). Similar to the preceding robustness tests, the interaction coefficient estimates on Firm Q_commit*IRR and Firm EPS Growth_commit*IRR are both negative and significant at 5%.

References

Aboody, D., Even-Tov, O., Lehavy, R., & Trueman, B. (2018). Overnight returns and firm-specific investor sentiment. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109017000989.

Agrawal, A., & Cooper, T. (2015). Insider trading before accounting scandals. Journal of Corporate Finance,34, 169–190.

Amiram, D., & Kalay, A. (2017). Industry characteristics, risk premiums, and debt pricing. The Accounting Review,92, 1–27.

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies,58, 277–297.

Badertscher, B. A., Hribar, S. P., & Jenkins, N. T. (2011). Informed trading and the market reaction to accounting restatements. The Accounting Review,86, 1519–1547.

Baker, M., & Wurgler, J. (2006). Investor sentiment and the cross-section of stock returns. Journal of Finance,61, 1645–1680.

Ball, B. (2009). Market and political/regulatory perspectives on the recent accounting scandals. Journal of Accounting Research,47, 277–323.

Barber, B., Odean, T., & Zhu, N. (2009). Do retail trades move markets? Review of Financial Studies,22, 151–186.

Barber, B. M., & Odean, T. (2001). Boys will be boys: Gender, overconfidence, and common stock investment. Quarterly Journal of Economics,116, 261–292.

Bardos, K. S., Golec, J., & Harding, J. P. (2011). Do investors see through mistakes in reported earnings? Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis,46, 1917–1946.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management,17, 99–120.

Beneish, M. D. (1999). The detection of earnings manipulation. Financial Analysts Journal,55, 24–36.

Berkman, H., Koch, P., Tuttle, L., & Zhang, Y. (2012). Paying attention: Overnight returns and the hidden cost of buying at the open. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 47, 715–741.

Bhattacharya, U., & Marshall, C. D. (2012). Do they do it for the money? Journal of Corporate Finance,18, 92–104.

Bradshaw, M. T., Richardson, S. A., & Sloan, R. G. (2006). The relation between corporate financing activities, analysts forecasts and stock returns. Journal of Accounting and Economics,42, 53–85.

Brochet, F., Ferri, F., & Miller, G. S. (2016). Market valuation of anticipated governance changes: Evidence from contentious shareholder meetings. Columbia Business School Research Paper No. 16-47, 2016.

Burks, J. J. (2011). Are investors confused by restatements after Sarbanes–Oxley? Accounting Review,86, 507–539.

Burns, N., & Kedia, S. (2006). the impact of performance-based compensation on misreporting. Journal of Financial Economics,79, 35–67.

Burns, N., Kedia, S., & Lipson, M. (2010). Institutional ownership and monitoring: Evidence from financial misreporting. Journal of Corporate Finance,16, 443–455.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2005). Microeconometrics: Methods and applications. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Carcello, J. V., Neal, T. L., Palmrose, Z. V., & Scholz, S. (2011). CEO involvement in selecting board members, audit committee effectiveness, and restatements. Contemporary Accounting Research,28, 396–430.

Carter, M., & Lynch, L. (2001). An examination of executive stock option repricing. Journal of Financial Economics,61, 207–225.

Cohen, J., Ding, Y., Lesage, C., & Stolowy, H. (2017). Media bias and the persistence of the expectation gap: An analysis of press articles on corporate fraud. Journal of Business Ethics,144, 637–659.

Collins, D. W., Kothari, S. P., & Rayburn, J. D. (1987). Firm size and the information content of prices with respect to earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics,9, 111–138.

Crutchley, C. E., Jensen, M., & Marshall, B. B. (2007). Climate for scandal: Corporate environments that contribute to accounting fraud. Financial Review,42, 53–73.

Daniel, K., Hirshleifer, D., & Subrahmanyam, A. (2001). Overconfidence, arbitrage, and equilibrium asset pricing. Journal of Finance,56, 921–965.

Dechow, P. M., Ge, W. L., Larson, C. R., & Sloan, R. G. (2011). Predicting material accounting misstatements. Contemporary Accounting Research,28, 17–82.

Dechow, P., Hutton, A., & Kim., J., & Sloan, R. (2012). Detecting earnings management: a new approach. Journal of Accounting Research, 50(2), 275–334.

Dechow, P. M., Sloan, R. G., & Sweeney, A. P. (1996). Causes and consequences of earnings misstatement: An analysis of firms subject to enforcement actions by the SEC. Contemporary Accounting Research,13, 1–36.

Dichev, I. D., & Skinner, D. J. (2002). Large-sample evidence on the debt covenant hypothesis. Journal of Accounting Research,40, 1091–1123.

Dyck, A., Morse, A., & Zingales, L. (2010). Who blows the whistle on corporate fraud? Journal of Finance,65, 2213–2253.

El-Gazzar, S. M. (1998). Pre-disclosure information and institutional ownership: A cross-sectional examination of market revaluations during earnings announcement periods. The Accounting Review,73, 119–129.

Erickson, T., Jiang, C. H., & Whited, T. M. (2014). Minimum distance estimation of the errors-in-variables model using linear cumulant equations. Journal of Econometrics,183, 211–221.

Erickson, T., & Whited, T. M. (2012). Treating measurement error in Tobin’s q. Review of Financial Studies,25, 1286–1329.

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1997). Industry costs of equity. Journal of Financial Economics,43, 153–193.

Files, R., Swanson, E., & Tse, S. (2009). Stealth disclosure of accounting restatements. The Accounting Review,84, 1495–1520.

General Accounting Office (GAO). (2002). Financial statement restatements—Trends, market impacts, regulatory responses, and remaining challenges (GAO-03-138). Washington, DC: Report to Congressional Committees.

General Accountability Office (GAO). (2006). Financial restatements: Update of public company trends, market impacts, and regulatory enforcement activities (GAO-06-678). Washington, DC: Report to Congressional Committees.

Gong, G., Li, L., & Zhou, L. (2013). Earnings non-synchronicity and voluntary disclosure. Contemporary Accounting Research,30, 1560–1589.

Harris, J. D., & Bromiley, P. (2006). Incentives to cheat: The influence of executive compensation and firm performance on financial misrepresentation. Organization Science,18, 350–367.

Hass, L. H., Tarsalewska, M., & Zhan, F. (2016). Equity incentives and corporate fraud in China. Journal of Business Ethics,138, 723–742.

Hawawini, G., Subramanian, V., & Verdin, P. (2003). Is performance driven by industry- or firm-specific factors? A new look at the evidence. Strategic Management Journal,24, 1–16.

Healy, P. M. (1985). The effect of bonus schemes on accounting decisions. Journal of Accounting and Economics,7, 85–107.

Hennes, K. M., Leone, A. J., & Miller, B. P. (2008). The importance of distinguishing errors from irregularities in restatement research: The case of restatements and CEO/CFO turnover. The Accounting Review,83, 1487–1519.

Hertzberg, A. (2005). Managerial incentives, misreporting, and the timing of social learning: A theory of slow booms and rapid recessions. Working Paper, Northwestern University.

Hirshleifer, D. (2001). Investor psychology and asset pricing. Journal of Finance, 56, 1533–1597.

Hribar, P., & Jenkins, N. T. (2004). The effect of accounting restatements on earnings revisions and the estimated cost of capital. Review of Accounting Studies,9, 337–356.

Hribar, P., & McInnis, J. (2012). Investor sentiment and analysts’ earnings forecast errors. Management Science,58, 293–307.

Hribar, P., Melessa, S., Small, R., & Wilde, J. (2017). Does managerial sentiment affect accrual estimates? Evidence from the banking industry. Journal of Accounting and Economics,63, 26–50.

Huber, P. J. (1967). The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under non-standard conditions. In Proceedings of the fifth Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability (Vol. 1, pp.221–233). Berkely, CA: University of California Press.

Hutton, A. P., Lee, L. F., & Shu, S. Z. (2012). Do managers always know better? The relative accuracy of management and analyst forecasts. The Accounting Review,50, 1217–1244.

Jones, K. L., Krishnan, G. V., & Melendrez, K. D. (2008). Do Models of discretionary accruals detect actual cases of fraudulent and restated earnings? An empirical analysis. Contemporary Accounting Research,25, 499–531.

Karpoff, J., Koester, A., Lee, D., & Martin, G. (2017). Proxies and databases in financial misconduct research. The Accounting Review,92, 129–163.

Kayo, E. K., & Kimura, H. (2011). Hierarchical determinants of capital structure. Journal of Banking & Finance,35, 358–371.

Kedia, S., & Philippon, T. (2009). The economics of fraudulent accounting. Review of Financial Studies,22, 2169–2199.

Kinney, W. R., Jr., Palmrose, Z. V., & Scholz, S. (2004). Auditor independence, non-audit services, and restatements: Was the U.S. government right? Journal of Accounting Research,42, 561–588.

Kothari, S. P., Leone, A., & Wasley, C. E. (2005). Performance matched discretionary accrual measures. Journal of Accounting and Economics,39, 163–197.

Lambrecht, B. (2001). The impact of debt financing on entry and exit in a duopoly. Review of Financial Studies,14, 765–804.

Lemmon, M., & Portniaguina, E. (2006). Consumer confidence and asset prices: Some empirical evidence. Review of Financial Studies,19(1), 499–530.

Li, F., Lundholm, R., & Minnis, M. (2012). A measure of competition based on 10-k filings. The Accounting Review,51, 399–436.

Liu, M. H. (2011). Analysts’ incentives to produce industry-level versus firm-specific information. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis,46, 757–784.

Loughran, T., & Ritter, J. (2000). Uniformly least powerful tests of market efficiency. Journal of Financial Economics, 55, 361–389.

Malmendier, U., & Tate, G. (2005). CEO overconfidence and corporate investment. Journal of Finance,60, 2661–2700.

McGahan, A., & Porter, M. (2002). What do we know about variance in accounting profitability? Management Science,48, 834–851.

Myers, R. (2016). The rising risk of being CFO. CFO magazine, December 15, 2016. http://ww2.cfo.com/risk-management/.

Nguyen, D., Hagendorff, J., & Eshraghi, A. (2016). Can Bank Boards Prevent Misconduct? Review of Finance, 20, 1–36.

Palmrose, Z. V., Richardson, V. J., & Scholz, S. (2004). Determinants of market reactions to restatement announcements. Journal of Accounting and Economics,37, 59–89.

Petersen, M. (2009). Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: Comparing approaches. Review of Financial Studies,22, 435–480.

Piotroski, J. D., & Roulstone, D. T. (2004). The influence of analysts, institutional investors, and insiders on the incorporation of market, industry, and firm-specific information into stock prices. The Accounting Review,79, 1119–1151.

Porter, M. (1991). Towards a dynamic theory of strategy. Strategic Management Journal,12, 95–117.

Povel, P., Singh, R., & Winton, A. (2007). Booms, busts, and fraud. Review of Financial Studies,20, 1219–1254.

Rauh, J., & Sufi, A. (2012). Explaining corporate capital structure: Product markets, leases, and asset similarity. Review of Finance,16, 115–155.

Rogers, W. H. (1993). Regression standard errors in clustered samples. Stata Technical Bulletin,13, 19–23.

Roll, R. (1988). R2. Journal of Finance, 43(3), 541–566.

Russo, J. E., & Schoemaker, P. (1992). Managing overconfidence. Sloan Management Review,33, 7–17.

Scheinkman, J. A., & Xiong, W. (2003). Overconfidence and speculative bubble. Journal of Political Economy,111, 1183–1220.

Schmalensee, R. (1985). Do markets differ much? American Economic Review,75, 341–351.

Simpson, A. (2013). Does investor sentiment affect earnings management? Journal of Business Finance and Accounting,40, 869–900.

Song, F., & Thakor, A. V. (2006). Information control, career concerns, and corporate governance. Journal of Finance,61, 845–1896.

Wang, T. Y. (2011). Corporate securities fraud: Insights from a new empirical framework. Journal of Law Economics and Organization,29(3), 535–568.

Wang, T. Y., & Winton, A. (2014). Product market interactions and corporate fraud. Working Paper. University of Minnesota.

Wang, T. Y., Winton, A., & Yu, X. Y. (2010). Corporate fraud and business conditions: Evidence from IPOs. Journal of Finance,65, 2255–2292.

White, H. (1980). A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica, 48, 817–838.

Williams, R. (2012). Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal effects. The Stata Journal,12, 308–331.

Young, S., & Peng, E. (2013). An analysis of accounting frauds and the timing of analyst coverage decisions and recommendation revisions: Evidence from the US. Working Paper.

Zhao, Y., & Chen, K. H. (2008). The influence of takeover protection on earnings management. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting,35, 347–375.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Steven Dellaportas (the editor) and two anonymous referees for their very helpful comments. We thank Jonathan M. Karpoff, Allison Koester, D. Scott Lee and Gerald S. Martin who generously shared with us the Federal Securities Regulation (FSR) database. We thank Andrew J. Leone for generously sharing the General Accountability Office (GAO) data on classification of errors and irregularities. We appreciate insightful comments from Assaf Eisdorfer, Efdal Misirli, John Clapp, Joseph Golec, John Glascock and seminar participants at University of Connecticut, the 2016 Annual Meeting of Southern Finance Association (SFA) and the 4th India Finance Conference.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hegde, S., Zhou, T. Predicting Accounting Misconduct: The Role of Firm-Level Investor Optimism. J Bus Ethics 160, 535–562 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3848-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3848-8

Keywords

- Investor optimism

- Financial reporting

- Accounting misconduct

- Irregularity

- Earnings management

- Market reactions