Abstract

Purpose

In the BRCAsearch study, unselected breast cancer patients were prospectively offered germline BRCA1/2 mutation testing through a simplified testing procedure. The purpose of the present study was to evaluate satisfaction with the BRCAsearch testing procedure and, furthermore, to report on uptake rates of prophylactic surgeries among mutation carriers.

Methods

Pre-test information was provided by a standardized invitation letter instead of in-person genetic counseling. The patients were offered contact with a genetic counselor for telephone genetic counseling if they felt a need for that. Mutation carriers were telephoned and given a time for a face-to-face post-test genetic counseling appointment. Non-carriers were informed about the test result through a letter. One year after the test results were delivered, a study-specific questionnaire was mailed to the study participants who had consented to testing. The response rate was 83.1% (448 of 539).

Results

A great majority (96.0%) of the responders were content with the method used for providing information within the study, and 98.7% were content with having pursued genetic testing. 11.1% answered that they would have liked to receive more oral information. In an adjusted logistic regression model, patients with somatic comorbidity (OR 2.56; P = 0.02) and patients born outside of Sweden (OR 3.54; P = 0.01) were more likely, and patients with occupations requiring at least 3 years of university or college education (OR 0.37; P = 0.06) were less likely to wanting to receive more oral information. All 11 mutation carriers attended post-test genetic counseling. At a median follow-up of 2 years, the uptake of prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy was 100%, and the uptake of prophylactic mastectomy was 55%.

Conclusions

Satisfaction with a simplified BRCA1/2 testing procedure was very high. Written pre-test information has now replaced in-person pre-test counseling for breast cancer patients in our health care region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Simplified methods, such as telephone counseling or written information, are increasingly used instead of standard face-to-face pre-test genetic counseling [1,2,3,4,5]. We have recently reported the results of the prospective BRCAsearch study, where unselected breast cancer patients were offered germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation testing [6]. Instead of pre-test genetic counseling, the patients received a standardized information letter. The study procedure offers an example of how genetic testing could be undertaken on a large scale, enabling BRCA testing to be expanded to a much larger number of patients than what has previously been possible.

Studies on patient satisfaction with genetic counseling have reported high levels of satisfaction, regardless if the counseling was conducted in-person, by telephone, or if the information was primarily provided through written material [7,8,9,10,11]. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has reported on patient satisfaction with written pre-test written information offered to unselected breast cancer patients. In this paper, we present the results of the 1-year follow-up patient-reported questionnaire from the BRCAsearch study. The questionnaire included questions regarding satisfaction with the study procedure and genetic testing.

The mode of delivery of genetic counseling and testing services could be associated with uptake rates of cancer risk management strategies among mutation carriers [12]. Importantly, prophylactic surgeries in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers lead to a significant survival benefit [13]. It is therefore crucial to rule out any negative impact on the uptake rates of prophylactic surgeries before new testing procedures are implemented in daily practices. In this paper, we also present the uptake rates of prophylactic surgeries among the mutation carriers identified within the BRCAsearch study.

Materials and methods

The BRCAsearch study

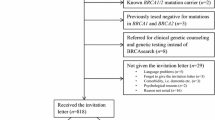

The study population of BRCAsearch has been described in detail elsewhere [6, 14]. Briefly, patients newly diagnosed with breast cancer were prospectively offered germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation testing, unselected for age at diagnosis or family history of cancer (BRCAsearch, ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02557776). Pre-test information was provided by a standardized invitation letter instead of in-person genetic counseling. The patients were offered contact with a genetic counselor for telephone genetic counseling if they felt a need for that. As previously reported, the invitation letter was given to 818 patients during February 2015–August 2016. One patient only had lobular carcinoma in situ, and she was therefore excluded from further analyses. Twelve patients did not consent to further follow-up, and were also excluded. Among the remaining 805 patients, 539 (67.0%) consented to germline testing. Only 11 out of 539 tested patients contacted us for questions related to genetic counseling [6]. Mutation carriers were telephoned and given a time for a face-to-face post-test genetic counseling appointment within 1 week. Non-carriers were informed about the test result through a letter.

Present study population and study procedure

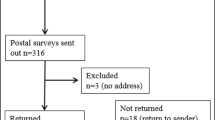

One year after delivery of the test results, a study-specific questionnaire was mailed to participants who had consented to testing. The questionnaire included 6 questions related to satisfaction with the study procedure and genetic testing (Table 1). The response rate was 83.1% (448 of 539). Responders were older than non-responders (mean age: 62.5 vs. 59.1 years; P = 0.01), and less likely to be born outside of Sweden (6.9 vs. 15.4%; P = 0.008) (Supplementary table S1). Responders (n = 448) constituted the study population for the present paper. Patients who did not elect to participate in the BRCAsearch study, and as a consequence were not tested, were not part of this follow-up.

Data collection

As detailed in a previous paper [14], the clinical data were abstracted from the medical records. Different occupations were categorized into three groups based on the minimum level of education required. Group 1 consisted of occupations requiring little formal education other than compulsory school. Occupations requiring some, but less than 3 years, of vocational school or college education were allocated to Group 2. Group 3 consisted of occupations requiring at least 3 years of college or university education, equivalent to a bachelor’s degree or a master’s degree. Information about somatic comorbidity was coded according to the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) [15]. A recent diagnosis of breast cancer rendered 2 points, and accordingly, no patient had a CCI of less than 2. Age categories are sometimes included in the CCI, but since we aimed to include age as a separate variable in the logistic regression model, CCI in this paper refers to CCI excluding age.

Statistical analyses

Differences in patient characteristics between patients who returned the questionnaire and patients who did not return the questionnaire were assessed using Pearson Chi-square test (χ2) and independent samples t test. Regarding predictors of wanting to receive more oral information (Table 2), unadjusted associations were evaluated using logistic regression. In the multivariable logistic regression model, variables with a significance of P ≤ 0.25 in unadjusted analysis were included. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Satisfaction with testing and with the study procedure

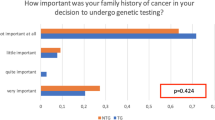

Overall, the study participants were satisfied with the study procedure (Table 1). 97.1% expressed that they had understood the information provided within the study, and 96.0% were content with the method used for providing information within the study. 97.8% would recommend a female friend with breast cancer to pursue genetic testing in the way that they had done, and 98.7% were content with having pursued genetic testing. On the question “Would you have liked to receive more oral information,” a majority (88.9%) answered “Not at all” or “To a low extent,” but 11.1% (n = 49) responded “To a high extent” or “To a very high extent.” Still, out of 49 patients who answered that they wanted to receive more oral information, only 5 had contacted us for questions, and 45 out of 49 reported that they were content with the method used for providing information within the study.

Exploratory analyses were conducted to investigate if any patient characteristics were associated with a wish to receive more oral information (Table 2). In the adjusted logistic regression model, patients with somatic comorbidity (OR 2.56; P = 0.02) and patients born outside of Sweden (OR 3.54; P = 0.01) were more likely, and patients with occupations requiring at least 3 years of university of college education (OR 0.37; P = 0.06) were less likely to wanting to receive more oral information.

Within the present study population, 29 patients had contacted us for questions, and consequently, they had received pre-test telephone genetic counseling in addition to the written information provided in the invitation letter. Only 3 out of 29 answered “Not at all” or “To a low extent” on the question “Are you content with the method used for providing information within the study (written information with the possibility of further contact).” The remaining 26 were content with the method.

Mutation carriers

Eleven germline BRCA1/2 mutation carriers were identified within the BRCAsearch study (BRCA1, n = 2; BRCA2, n = 9) [6]. All of them attended in-person post-test genetic counseling. At a median follow-up of 2 years, one mutation carrier had been diagnosed with a local recurrence following breast-conserving surgery; all other mutation carriers were free of breast cancer recurrence. Eleven (100%) had undergone prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy, and six (55%) had undergone prophylactic mastectomy.

All mutation carriers were content with having pursued genetic testing, and 10 out of 11 were content with the method used for providing information within the study. One of them would have liked to receive more oral information.

Discussion

We offered a simplified and streamlined BRCA1/2 testing protocol to unselected breast cancer patients. Among the patients who opted for testing (67.0%), satisfaction with the testing procedure was very high. Also within the small group of patients who turned out to be mutation carriers (2.0%), there was a high degree of satisfaction with the testing procedure.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to assess satisfaction in unselected breast cancer patients who have undergone germline BRCA1/2 testing without prior face-to-face genetic counseling. Similar to the results of our study, previous studies in cohorts enriched for mutation carriers and cohorts from clinical genetics departments have reported high levels of satisfaction with the standard procedure of in-person counseling, with telephone counseling, and with simplified methods based on written material [8, 9, 11]. Metcalfe et al. found a high rate of satisfaction (92.8%) with the testing procedure among unselected Jewish women who underwent BRCA1/2 testing without pre-test genetic counseling [7]. One could conclude that a great majority of all patients seem to be satisfied with any type of delivery of pre-test information. Given that

-

a)

proper post-test genetic counseling carried out by a genetics professional is important for the uptake rates of prophylactic surgeries [12],

-

b)

mutation carriers who are aware of their mutation carrier status—in contrast to mutation carriers who are not aware of their mutation carrier status—can opt for prophylactic surgeries or surveillance programs, thereby decreasing their risk of cancer-related death [16],

-

c)

currently used testing procedures based on selection criteria to merit testing fail to detect up to half of the mutation carriers [17,18,19,20],

it seems prudent to recommend simplified methods for pre-test information and, instead, let the scarce resource of genetics professionals focus on the post-test genetic counseling for the small minority of cancer patients who will turn out to be mutation carriers. In our opinion, the results of our present study lend support to such an approach. Importantly, all BRCA1/2 mutation carriers identified within the study accepted the offer of in-person post-test genetic counseling, and with only 2 years of median follow-up, all of them had opted for prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy.

A minority of breast cancer patients offered germline BRCA1/2 testing would likely benefit from pre-test counseling—telephone or in-person—as a complement to written information. In our study, 11.1% reported that they would have liked to receive more oral information. Using data extracted from the medical records, we were able to identify some characteristics associated with a higher likelihood of wanting more oral information: patients with somatic comorbidity and patients born outside of Sweden were more likely, and patients with a high level of education were less likely to wanting to receive more oral information. However, we do not believe that the results of these exploratory analyses should have any clinical impact. When a standardized written pre-test information is used, we consider it very important to offer all patients the possibility of complementary telephone or in-person counseling, and consider it mandatory to offer all mutation carriers post-test in-person genetic counseling.

For many breast cancer patients, simplified methods might even be preferable over standard pre-test counseling. In the “DNA-direct” study from the Netherlands, Sie et al. found that some patients, who were still undergoing breast cancer treatment, opted for simplified pre-test information because an extra hospital visit in a time period of chemotherapy or radiotherapy treatment was considered an extra burden, while reading information at home made genetic testing accessible [5].

There are limitations to our study. First, we used a questionnaire that was developed for the study. The reason for this was that we did not find any validated questionnaire fulfilling our requirements for evaluation of the quite specific study procedure. The questions and answers (translated from Swedish to English) of our questionnaire are presented in Table 1, making it possible for the reader to assess the utility of the questionnaire. Second, there is the issue of representativity. A response rate of 83.1% is good for a mailed 1-year follow-up questionnaire. Still, one important aspect to consider is that all the patients who were mailed the questionnaire had opted for genetic testing. Such patients are obviously biased towards a positive attitude to genetic testing in general. It is not surprising that they report a high level of satisfaction. Due to ethical regulations, we were not able to survey patients who were offered, but did not pursue, genetic testing (266 of 805; 33%), and consequently, we cannot assess whether those patients were satisfied with—or even read—the written information that was provided.

In summary, satisfaction with a simplified testing procedure was very high among unselected breast cancer patients undergoing germline BRCA1/2 testing. Based on the results of the BRCAsearch study, in conjunction with the similar results of other studies, written pre-test information has replaced in-person pre-test counseling for recently diagnosed breast cancer patients in our health care region. As a consequence, germline BRCA1/2 testing can now be offered to a much larger number of breast cancer patients than what previously was possible.

References

Hoberg-Vetti H, Bjorvatn C, Fiane BE, Aas T, Woie K, Espelid H, Rusken T, Eikesdal HP, Listol W, Haavind MT, Knappskog PM, Haukanes BI, Steen VM, Hoogerbrugge N (2016) BRCA1/2 testing in newly diagnosed breast and ovarian cancer patients without prior genetic counselling: the DNA-BONus study. Eur J Hum Genet 24(6):881–888. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2015.196

Kinney AY, Steffen LE, Brumbach BH, Kohlmann W, Du R, Lee JH, Gammon A, Butler K, Buys SS, Stroup AM, Campo RA, Flores KG, Mandelblatt JS, Schwartz MD (2016) Randomized noninferiority trial of telephone delivery of BRCA1/2 genetic counseling compared with in-person counseling: 1-year follow-up. J Clin Oncol 34(24):2914–2924. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2015.65.9557

Metcalfe KA, Poll A, Royer R, Llacuachaqui M, Tulman A, Sun P, Narod SA (2010) Screening for founder mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 in unselected Jewish women. J Clin Oncol 28(3):387–391. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2009.25.0712

Schwartz MD, Valdimarsdottir HB, Peshkin BN, Mandelblatt J, Nusbaum R, Huang AT, Chang Y, Graves K, Isaacs C, Wood M, McKinnon W, Garber J, McCormick S, Kinney AY, Luta G, Kelleher S, Leventhal KG, Vegella P, Tong A, King L (2014) Randomized noninferiority trial of telephone versus in-person genetic counseling for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 32(7):618–626. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2013.51.3226

Sie AS, van Zelst-Stams WA, Spruijt L, Mensenkamp AR, Ligtenberg MJ, Brunner HG, Prins JB, Hoogerbrugge N (2014) More breast cancer patients prefer BRCA-mutation testing without prior face-to-face genetic counseling. Fam Cancer 13(2):143–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-013-9686-z

Nilsson MP, Torngren T, Henriksson K, Kristoffersson U, Kvist A, Silfverberg B, Borg A, Loman N (2018) BRCAsearch: written pre-test information and BRCA1/2 germline mutation testing in unselected patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 168(1):117–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-017-4584-y

Metcalfe KA, Poll A, Llacuachaqui M, Nanda S, Tulman A, Mian N, Sun P, Narod SA (2010) Patient satisfaction and cancer-related distress among unselected Jewish women undergoing genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2. Clin Genet 78(5):411–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01499.x

Peshkin BN, Kelly S, Nusbaum RH, Similuk M, DeMarco TA, Hooker GW, Valdimarsdottir HB, Forman AD, Joines JR, Davis C, McCormick SR, McKinnon W, Graves KD, Isaacs C, Garber J, Wood M, Jandorf L, Schwartz MD (2016) Patient perceptions of telephone vs. in-person BRCA1/BRCA2 genetic counseling. J Genet couns 25(3):472–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-015-9897-6

Platten U, Rantala J, Lindblom A, Brandberg Y, Lindgren G, Arver B (2012) The use of telephone in genetic counseling versus in-person counseling: a randomized study on counselees’ outcome. Fam Cancer 11(3):371–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-012-9522-x

Rothwell E, Kohlmann W, Jasperson K, Gammon A, Wong B, Kinney A (2012) Patient outcomes associated with group and individual genetic counseling formats. Fam Cancer 11(1):97–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-011-9486-2

Sie AS, Spruijt L, van Zelst-Stams WA, Mensenkamp AR, Ligtenberg MJ, Brunner HG, Prins JB, Hoogerbrugge N (2016) High satisfaction and low distress in breast cancer patients one year after BRCA-mutation testing without prior face-to-face genetic counseling. J Genet Couns 25(3):504–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-015-9899-4

Pal T, Lee JH, Besharat A, Thompson Z, Monteiro AN, Phelan C, Lancaster JM, Metcalfe K, Sellers TA, Vadaparampil S, Narod SA (2014) Modes of delivery of genetic testing services and the uptake of cancer risk management strategies in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. Clin Genet 85(1):49–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/cge.12130

Hartmann LC, Lindor NM (2016) Risk-reducing surgery in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 374(24):2404. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1602861

Nilsson MP, Nilsson ED, Silfverberg B, Borg A, Loman N (2018) Written pretest information and germline BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant testing in unselected breast cancer patients: predictors of testing uptake. Genet Med. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-018-0021-9

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40(5):373–383

Kurian AW, Sigal BM, Plevritis SK (2010) Survival analysis of cancer risk reduction strategies for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol 28(2):222–231. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.22.7991

Ayme A, Viassolo V, Rapiti E, Fioretta G, Schubert H, Bouchardy C, Chappuis PO, Benhamou S (2014) Determinants of genetic counseling uptake and its impact on breast cancer outcome: a population-based study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 144(2):379–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-014-2864-3

Moller P, Hagen AI, Apold J, Maehle L, Clark N, Fiane B, Lovslett K, Hovig E, Vabo A (2007) Genetic epidemiology of BRCA mutations–family history detects less than 50% of the mutation carriers. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 43(11):1713–1717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2007.04.023

Nilsson MP, Winter C, Kristoffersson U, Rehn M, Larsson C, Saal LH, Loman N (2017) Efficacy versus effectiveness of clinical genetic testing criteria for BRCA1 and BRCA2 hereditary mutations in incident breast cancer. Fam Cancer 16(2):187–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-016-9953-x

Wood ME, Kadlubek P, Pham TH, Wollins DS, Lu KH, Weitzel JN, Neuss MN, Hughes KS (2014) Quality of cancer family history and referral for genetic counseling and testing among oncology practices: a pilot test of quality measures as part of the American Society of Clinical Oncology Quality Oncology Practice Initiative. J Clin Oncol 32(8):824–829. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2013.51.4661

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the patients for participation in the BRCAsearch study, and thank the nurses and surgeons of the Breast Cancer Surgery Units in Helsingborg, Kristianstad, and Malmö for patient recruitment.

Funding

The work was funded by grants from Skåne County Council’s Research and Development Foundation, BioCARE, Mrs. Berta Kamprad Foundation, Gunnar Nilsson Cancer Foundation, and Swedish Cancer Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NL, ÅB, and MPN conceived of the study. MPN and BS collected and categorized the clinical data. MPN and YB developed the study-specific questionnaire. MPN and EDN performed the statistical analyses and interpreted the results. MPN drafted the manuscript and all authors critically revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund (Dnr 2009/659, Dnr 2014/681), and complies with the current laws of Sweden. The study has been performed in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nilsson, M.P., Nilsson, E.D., Borg, Å. et al. High patient satisfaction with a simplified BRCA1/2 testing procedure: long-term results of a prospective study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 173, 313–318 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-5000-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-5000-y