Abstract

Three-dimensional direct numerical simulations of V-flames interacting with chemically inert walls in a fully developed turbulent channel flow have been performed under adiabatic and isothermal wall boundary conditions using single-step chemistry. These simulations are representative of stoichiometric methane-air mixture at unity Lewis number under atmospheric conditions. The turbulence in the non-reacting channel is representative of the friction velocity based Reynolds number \(Re_{\tau }=110\). Differences in the statistical behaviours of the mean values of progress variable, temperature, and density have been reported for different wall boundary conditions. It is found that the mean location of the oblique flame interacting with the wall is affected by the choice of the wall boundary condition used. The influence of these differences on the flame dynamics is investigated by analysing the statistical behaviours of the surface density function (SDF) and the strain rates, which govern the evolution of the SDF. The mean variation of the SDF and the flame displacement speed are strongly affected by the wall boundary condition within the viscous sub-layer region of the boundary layer. The behaviours of the normal and tangential strain rates are found to be influenced by not only the differences in the wall boundary conditions, but also by the distance from the wall. The differences in the displacement speed statistics for different wall boundary conditions and wall distance affect the behaviours of the normal strain rate arising due to flame propagation and curvature stretch. The changes in the SDF behaviour in the near wall region have been explained in terms of the statistics of effective normal strain rate experienced by the progress variable iso-surfaces under different wall boundary conditions and wall normal distances.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Flame-wall interaction (FWI) occurs in many engineering devices (e.g. spark ignition (SI) engines, gas turbines and micro-combustors), and modelling these phenomena remains challenging. During these events combustion is strongly influenced by the presence of walls, which may lead to flame quenching in the case of wall heat loss. The flame also has a significant effect on the flow near the wall as well as on the heat flux to the wall (Alshaalan and Rutland 2002). Consequently, the turbulence structure is altered by the presence of walls and the interaction of flame elements with walls leads to modifications of the underlying combustion processes (Alshaalan and Rutland 1998). In practice, limited information is available regarding the behaviour of turbulence and combustion processes during FWI in fully developed boundary layers.

Several experimental and numerical studies have focused on the issues related to FWI in different flame/flow configurations. Head-on quenching of premixed turbulent flames under isotropic turbulence conditions has been investigated in a two dimensional direct numerical simulation (DNS) by Poinsot et al. (1993), and extensively in three dimensional DNS studies by Chakraborty and co-workers (Ahmed et al. 2018; Lai and Chakraborty 2016a, b; Lai et al. 2017a, 2018a, b; Sellmann et al. 2017) for both unity and non-unity Lewis numbers. In these simulations there is no mean flow and the flame propagates towards the wall and is eventually quenched in the vicinity of the cold wall. A major drawback of these simulations is that the turbulence decays rapidly during the FWI process and cannot be easily quantified. These simulations still provide important physical insights into quenching distances and the influence of chemistry in FWI. The limitations related to the quantification of turbulence in FWI can be overcome by investigating fully developed turbulence in boundary layers. Such DNS studies have been performed by Bruneaux et al. (1996, 1997) in a constant density turbulent channel flow and this work has been extended by Alshaalan and Rutland (1998, 2002) by performing a V-flame simulation in a turbulent channel-Couette flow. These simulations demonstrate that the near-wall structures have a strong influence on the flame when it is in the vicinity of the wall. On the one hand, the flame is pushed towards the wall by turbulent structures leading to higher wall heat fluxes and localised flame quenching. On the other hand, these vortical structures transport unburned fluid away from the wall and carry it into the burned gases, consequently creating pockets of fresh gases in the burnt gas regions. More recently, FWI has been investigated in turbulent channel flow using DNS by Gruber et al. (2010) in the case of a V-flame, and by Gruber et al. (2012, 2018), Kitano et al. (2015) and Ahmed et al. (2019) in the case of turbulent boundary layer flashback. Statistically planar turbulent premixed flames impinging on a flat inert wall at different temperatures have been investigated by Zhao et al. (2018a, b, 2019). These studies have shown that the flame front has a strong influence on the approaching turbulence and at the same time the turbulence significantly affects the flame structure. Recent experimental findings for V-flames interacting with cold walls (Jainski et al. 2017a, b, 2018) and transient head-on quenching (Rißmann et al. 2017) have confirmed the DNS findings on the influence of the flame on turbulence and vice verca.

Current modelling approaches (i.e. Reynolds averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) or large eddy simulation (LES) techniques) used to simulate industrial scale combustors cannot accurately account for the influence of the boundary layer on flame dynamics involved in FWI. In turbulent premixed flames, the unclosed mean/filtered reaction rate is often closed using the gradient of the reaction progress variable (c) and relies on the generalised flame surface density (FSD) (Boger et al. 1998) or scalar dissipation rate (SDR) (Borghi and Dutoya 1979) modelling. Consequently, the statistical behaviour of the modulus of the reaction progress variable gradient \(|\nabla c|\), usually referred to as the surface density function (SDF), is of fundamental importance in the modelling of turbulent premixed flames (Kollmann and Chen 1998). A transport equation for SDF has been derived by Pope (1988) and Candel and Poinsot (1990) which demonstrates the roles of tangential strain rate and curvature in the evolution of \(|\nabla c|\). Further analysis on the transport of \(|\nabla c|\) based on a two-dimensional DNS has been performed by Kollmann and Chen (1998) who also analysed pocket formation in premixed flames. More recently, the strain rate and curvature dependence of the different terms of the SDF transport equation have been investigated for different turbulence conditions (Chakraborty and Cant 2005a; Kim and Pitsch 2007), fuels (Chakraborty et al. 2008, 2018), global Lewis numbers (Chakraborty and Klein 2008) and mean flame radii (Chakraborty and Klein 2009). The issues related to the relative alignment of \(\nabla c\) with the local principal strain rates have been investigated in several previous studies (Ahmed et al. 2014; Chakraborty and Swaminathan 2007; Kim and Pitsch 2007). These investigations demonstrate that \(\nabla c\) preferentially aligns with the most extensive principal strain rate when flame normal strain due to thermal expansion dominates over the straining induced by turbulent fluid motion. Whereas, a preferential alignment of \(\nabla c\) with the most compressive principal strain rate is obtained when turbulent straining is stronger than the flame-induced strain rate. The influences of normal and tangential strain rates arising from the non-material nature (i.e. flame normal motion) of the flame surface on the evolution of the SDF have been demonstrated in previous studies (Cifuentes et al. 2014; Dopazo and Cifuentes 2016; Dopazo et al. 2015, 2016), and these strain rates induced by flame propagation have been termed as additional strain rates.

Until recently, most numerical investigations of the SDF transport and its strain rate dependence have been performed on canonical configurations (i.e. flames interacting with isotropic decaying turbulence). Some attempts have been made to understand the influence of mean shear on the behaviour of the SDF in the case of Bunsen flames (Sankaran et al. 2007), turbulent jet flames under high Karlovitz numbers (Wang et al. 2017) and temporally evolving slot jet premixed flames (Chaudhuri et al. 2017). It has been found by Sankaran et al. (2007) that in the case of Bunsen flames, the flame thickens in the mean sense which is in contradiction to the earlier findings from a canonical configuration (Hawkes and Chen 2006). The statistical behaviour of the strain rate induced by flame propagation in the case of high Karlovitz number jet flames (Wang et al. 2017) has been found to be in contradiction with the earlier results obtained from flames interacting with decaying turbulence (Dopazo et al. 2015). The SDF statistics in the case of a turbulent bluff body burner have been found to be significantly affected by the downstream distance away from the bluff body due to variations in the hydrodynamic tangential strain rate (Sandeep et al. 2018). In this spirit, a DNS database of statistically stationary V-flames in a fully developed turbulent channel flow under both isothermal and adiabatic inert wall boundary conditions has been interrogated to extract statistical information regarding the behaviour of SDF and the terms of the SDF transport equation. Such analysis under both isothermal and adiabatic wall boundary conditions, to the best of our knowledge, has never been reported in the literature. The flames considered in the current work are representative of stoichiometric methane-air premixed combustion under low Mach and unity Lewis number conditions. The main objectives of this work are:

-

1.

To demonstrate the mean behaviour of the displacement speed \(S_{d}\) and the relative importances of its reaction, normal and tangential diffusion components in the near wall region in the case of oblique FWI.

-

2.

To investigate the statistics of normal and tangential strain rates on the evolutions of the magnitude of the gradient of reaction progress variable \(|\nabla c|\) (also known as SDF), which have implications on the modelling of FWI in fully developed boundary layers for isothermal and adiabatic wall boundary conditions.

The paper is organized as follows. In the next two sections the mathematical background for the current analysis and the details for the DNS data are provided. This is followed by the results, and the conclusions are summarized in the final section.

2 Mathematical Background

The reactive field is usually expressed in terms of the reaction progress variable as:

where \(Y_{F}\) is the fuel mass fraction and the subscripts R and P indicate the respective values of the fuel in the unburned and fully burned gases. The transport equation for the reaction progress variable is given by:

where \(\rho \) is the density, \(u_{j}\) is the velocity component in the jth direction, \(\alpha _{c}\) is the diffusivity of the progress variable and \(\dot{\omega }_{c}\) is the chemical reaction rate. Equation (2) can be expressed in the kinematic form for a given c iso-surface as:

where \(S_{d}\) is the displacement speed and is defined as (Echekki and Chen 1996):

Note that in Eq. (4) the displacement speed is affected by a reaction diffusion balance \(\dot{\omega }_{c}+\nabla \cdot (\rho \alpha _{c}\nabla c)\), density \(\rho \), and the SDF \(|\nabla c|\). As the displacement speed depends on the interaction between the molecular diffusion rate and the reaction rate, it is useful to express displacement speed in terms of three different components as \(S_{d}=S_{r}+S_{n}+S_{t}\). The expressions for the reaction component \(S_{r}\), normal diffusion component \(S_{n}\) and the tangential diffusion contribution \(S_{t}\) of displacement speed are given by Echekki and Chen (1999):

where \(\kappa _{m}=0.5\nabla \cdot \varvec{N}\) is the arithmetic mean of two principal flame curvatures and \(\varvec{N}=-\nabla c/|\nabla c|\) is the flame normal vector. According to these definitions a flame surface element with a positive (negative) curvature remains convex (concave) towards the reactants.

The transport equation for \(|\nabla c|\) can be written as (Chakraborty and Cant 2005a; Kim and Pitsch 2007; Sankaran et al. 2007):

where \(a_{T}=(\delta _{ij}-N_{i}N_{j})(\partial u_{i}/\partial x_{j})\) is the tangential strain rate. Using the chain rule on both sides of Eq. (6) yields (Chakraborty et al. 2018):

where \(V_{j}^{c}=(u_{j}+S_{d}N_{j})\) is the jth component of propagation velocity of a given c isosurface, \(a_{N}= N_{i}N_{j}\partial u_{i}/\partial x_{j}\) is the flame normal strain rate and \(a_{N}^{eff}\) is the effective normal strain rate that influences the evolution of \(|\nabla c|\). It is evident from Eq. (7) that an increase in \(a_{N}^{eff}\) leads to an increase in the normal distance between c isosurfaces, which consequently leads to a decrease in \(|\nabla c|\). In this regard, it is also useful to consider the evolution of the flame surface area, A (Dopazo et al. 2015; Dopazo and Cifuentes 2016; Candel and Poinsot 1990; Pope 1988):

In Eq. (8), \(2S_{d}\kappa _{m}\) is an additional contribution to the tangential strain rate due to flame propagation and \(a_{T}^{eff}\) is the effective tangential strain rate (Dopazo et al. 2015; Dopazo and Cifuentes 2016). The quantities \(a_{T}^{eff}\) and \(2S_{d}\kappa _{m}\) are alternatively referred to as stretch rate and curvature stretch, respectively (Candel and Poinsot 1990; Pope 1988). Note that there are different definitions for stretch rate available in the literature (de Goey and ten Thije Boonkkamp 1997), but a detailed comparison of these definitions is beyond the scope of the current work and the expression in Eq. (8) will be used in the following sections.

3 Direct Numerical Simulation Data

A well-known three-dimensional compressible DNS code SENGA+ (Jenkins and Cant 1999) has been used to simulate the oblique flame–wall interaction of a V-flame with inert isothermal and adiabatic walls in a fully developed turbulent channel flow. This configuration is similar to the one used in earlier works of Alshaalan and Rutland (1998), Alshaalan and Rutland (2002) and Gruber et al. (2010) on FWI under isothermal wall boundary conditions. The code employs high-order finite-difference (10th order for internal points and gradually decreasing to 2nd order at the non-periodic boundaries) and Runge–Kutta (3rd order explicit) schemes for spatial differentiation and time advancement, respectively. The governing equations of mass, momentum, energy, and species mass fractions are solved in a non-dimensional form and a single-step irreversible reaction \((Fuel+s\,\,Oxidiser\rightarrow (1+s)Products)\) (where s is the oxidiser-fuel ratio by mass) is used for the purpose of computational economy. This treatment for chemical reaction has been employed in several previous studies involving head-on quenching simulations of premixed turbulent flames under isotropic turbulence conditions (Poinsot et al. 1993; Sellmann et al. 2017; Lai and Chakraborty 2016a, b; Ahmed et al. 2018; Lai et al. 2017a, 2018a, b), head-on quenching in a turbulent channel flow without density change across the flame (Bruneaux et al. 1996) and a V-flame configuration (Alshaalan and Rutland 1998, 2002). It has also been demonstrated in previous studies that the inclusion of a detailed chemical mechanism along with variable transport properties does not alter the underlying flame dynamics (including the reaction progress variable gradient statistics which is the focus of this work) (Lai et al. 2018a) or the behaviour of flame–turbulence interaction in the presence of inert isothermal walls (Ahmed et al. 2018) in spite of some differences in heat release rate behaviour in the near-wall region between simple and detailed chemistry simulations. This is reflected in the increased CO and HO\(_2\) production in the vicinity of the wall based on detailed chemistry DNS data but it does not affect the statistics related to wall heat flux magnitude and flame quenching distance, which have been found to be in agreement with the corresponding values obtained from simple chemistry DNS data (Lai et al. 2018a). The models proposed for the FSD and SDR based on simple chemistry DNS data are shown to be valid for detailed chemistry DNS data in the case of FWI (Lai et al. 2018a). Furthermore, the wall heat flux and wall Peclet number obtained from simple chemistry DNS have been found to be in good agreement with experimental findings (Jarosinski 1986; Vosen et al. 1985; Huang et al. 1988). In fact, it has been shown in the past clearly and without any doubt that displacement speed statistics from simple chemistry (e.g. Chakraborty 2007; Chakraborty and Cant 2004, 2005a, b) and detailed chemistry DNS (e.g. Echekki and Chen 1996, 1999) are qualitatively similar. The same is true for the statistics of the reactive scalar gradient obtained from simple chemistry (Chakraborty and Cant 2005a; Chakraborty and Klein 2008; Chakraborty et al. 2013; Dopazo and Cifuentes 2016) and detailed chemistry (Chakraborty et al. 2008, 2013; Wang et al. 2017) DNS data. It has been found that models developed based on simple chemistry data (e.g. Lai and Chakraborty 2016b; Sellmann et al. 2017; Gao et al. 2014) perform equally well in the context of detailed chemistry and transport (Lai et al. 2018a; Gao et al. 2016). The fluid-dynamical aspects of flame–wall interaction based on simple chemistry DNS data of Alshaalan and Rutland (1998), Alshaalan and Rutland (2002) have been found to be consistent with detailed chemistry results of Gruber et al. (2010). In the recent experimental results of Jainski et al. (2017a), it has been shown that the models developed by using single-step chemistry DNS are able to represent global features of the near-wall FSD profiles obtained in experiments. The focus of the present work is neither ignition nor emissions but on fundamental flame–turbulence interaction in wall-bounded flows and this can be captured at least in a qualitative sense with the help of single-step chemistry.

The current simulations are representative of a stoichiometric methane-air mixture under atmospheric conditions, hence standard values of the Zeldovich number \(\beta _{z}=T_{a}(T_{ad}-T_{R})/T^{2}_{ad}\) (where \(T_{a}\) is the activation temperature, \(T_R\) is the reactant temperature and \(T_{ad}\) is the adiabatic flame temperature), Prandtl number Pr, and ratio of specific heats \(\gamma \) (i.e., \(\beta _{z}=6.0\), \(Pr=0.7\), and \(\gamma =1.4\)) are used where the Lewis numbers of all the species are taken to be unity. It has recently been shown in a DNS study of statistically planar methane-air flames with detailed chemistry and transport (Aspden et al. 2016) that the global Lewis number remains close to unity and the leading-order response of the flame speed to turbulence is primarily driven by the global Lewis number even under very intense turbulence conditions which justifies the use of unity Lewis number in this work. The heat release parameter \(\tau =(T_{ad}-T_{R})/T_{R}\) is taken to be 2.3 for the V-flames considered here, which corresponds to preheating of reactants to a temperature of \(T_R =730\) K. This value of \(T_R\) and the resulting \(\tau \) is consistent with the earlier detailed chemistry DNS of FWI in the case of a V-flame in a turbulent channel flow (Gruber et al. 2010), turbulent boundary layer flashback (Ahmed et al. 2019; Gruber et al. 2012; Kitano et al. 2015) and single-step chemistry V-flame DNS with FWI (Alshaalan and Rutland 1998, 2002) and without FWI (Dunstan et al. 2010).

An auxiliary DNS of inert fully developed turbulent-plane channel flow driven by a stream-wise constant pressure gradient is used to generate the initial conditions and the inflow data for the reacting flow simulation. It can be shown by an overall momentum balance that the pressure gradient is directly related to the shear stress \((\tau _{w}=\rho u^{2}_{\tau })\) as \(-\partial p/\partial x=\rho u^{2}_{\tau }/h\), where \(u_{\tau }=\sqrt{|\tau _{w}|/\rho }\) is the friction velocity, \(\tau _{w}=\mu \partial u/\partial y|_{y=0}\) is the wall shear stress, h is the channel half height, p is the pressure and \(\mu \) is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid. The bulk Reynolds number \( Re_{b}=\rho u_{b}2h/\mu \) for this simulation is 3285, where \(u_{b}=1/2h\int ^{2h}_{0}u\,dy\), and the wall friction based Reynolds number \(Re_{\tau }=\rho u_{\tau }h/\mu \) is 110. It is ensured that the minimum non-dimensional distance to the wall \(y^{+}=\rho u_{\tau }y/\mu \), where y is the distance from the wall, is at most \(y^{+}=0.6\) and the region \(y^{+}<1\) has at least two grid points to ensure appropriate resolution of the boundary layer as recommended by Moser et al. (1999). The domain size for this channel is \( 10.69h\times 2h\times 4h\) and \(1920\times 360\times 720\) equidistant grid points are used to discretise the computational domain.

Two different V-flame simulations have been performed in this work, one with adiabatic walls and the other with isothermal walls. The V-flame simulations are performed by placing a flame holder in a fully developed channel flow at \(y^{+}=55\) from the bottom wall (i.e. \(y=0.5h\)) with an approximate radius of \(R_{fth}\approx 0.2\delta _{th}\) (where \(\delta _{th}=\left( T_{ad}-T_{R}\right) /max|\nabla T|_{L}\) with the subscript L representing the laminar flame quantities) and the centre \(r_0\) positioned at 0.83h from the inlet of the channel, which ensures that the flame interacts with the bottom wall at a reasonable distance and also that the viscous boundary layer is not influenced by the flame holder and any effects seen in the boundary layer downstream of the flame holder are due to thermal expansion arising from chemical reaction. At the flame holder, the species, temperature and velocity distributions are imposed using a presumed Gaussian function following Dunstan et al. (2010). The Gaussian weighting function is defined in terms of the radial distance from \(r_0\) as:

where the constants A and \(\xi \) have been adjusted to produce the desired value of \(R_{fth}\). The sink or source terms appearing in the governing equations are evaluated by using \(S_m=g(r)(u_i-\overline{u}_{i0})\) and \(S_s=g(r)(Y_{\alpha }-Y_{\alpha ,P})\) for \(\alpha =1\ ...\ N-1\), where \(Y_{\alpha ,P}\) is the burned gas value of the species mass fraction at equilibrium and \(\overline{u}_{i0}\) is the initial mean velocity. The flame holder can be considered to represent a catalytic wire aligned in the periodic direction, but the intention is not to create the conditions representative of an actual flame holder, and only to stabilise the flame in the least numerically intrusive manner. Consequently, the formation of boundary layer on the flame holder and the effects of shear generated turbulence due to the flame holder are not considered in this analysis. The implementation of the flame holder has been validated by carrying out simulations without FWI for the parameters considered by Dunstan et al. (2010) and comparing the turbulent flame speed downstream of the flame holder (results not shown here).

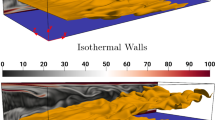

The velocity fluctuations introduced at the inflow of the reacting channel are obtained by temporal sampling of the temporally evolving turbulence at a fixed streamwise location in the auxiliary non-reacting simulation. Note that the time step chosen for the non-reacting simulation, while the data is being sampled, is the same as that of the reacting flow simulation. The set-up for the V-flame calculation is shown in Fig. 1, where the progress variable is defined in terms of the fuel mass fraction (see Eq. 1). Navier–Stokes characteristic boundary conditions (NSCBC) (Yoo and Im 2007) are used in the x and y directions. The boundary conditions are inflow with specified species mass fractions, density and velocity components at \(x=0\) and partially non-reflecting outflow at \(x=10.69h\) planes; no slip conditions are imposed for velocity at the walls (i.e. \(y=0\) and \(y=2h\)), while the temperature boundary condition is specified using zero gradient/ homogeneous Neumann boundary conditions (i.e. \(\partial T/\partial y|_{y=0{\text { or }}y=2h}=0\)) in the case of adiabatic walls and Dirichelet (i.e. \(T_{wall}=T_R\)) conditions are used for the case with isothermal walls. The boundaries in z direction are treated as periodic. The walls are assumed to be inert and impermeable, hence normal mass flux for all species is set to zero at the walls. The flame speed to friction velocity ratio \(S_L/u_{\tau }=0.7\) and the laminar flame thermal thickness \(\delta _{th}\) is resolved using approximately 8 grid points. The simulations have been performed for approximately 3 flow through times and the data has been sampled after 1 flow through time once the initial transience have decayed. Note that under the current flow conditions 1 flow through time is enough to obtain a statistically stationary solution for the mean turbulent kinetic energy statistics. The instantaneous flame structures represented by the \(c=0.5\) isosurface for the two cases considered in this work along with the normalised vorticity magnitude \(\Omega =\sqrt{\omega _{i}\omega _{i}}\times h/u_{\tau }\) (where \(\omega _{i}\) is the component of vorticity) are shown in Fig. 1. The influence of the walls on \(\Omega \) and the existence of wall ejections due to the introduction of the fully developed boundary layer at the inflow are clearly visible in both cases.

In the post-processing of the DNS data, the Reynolds averaged quantities (denoted by \(\overline{\lambda }\)), Favre averaged quantities (denoted by \(\widetilde{\lambda }=\overline{\rho \lambda }/\overline{\rho }\)), correlations involving Reynolds fluctuations (denoted by \( \lambda ^{\prime }=\lambda -\overline{\lambda }\)) and Favre fluctuations (denoted by \( \lambda ^{\prime \prime }=\lambda -\widetilde{\lambda }\)) have been evaluated by time averaging and subsequently using spatial averaging in the periodic directions, where \(\lambda \) refers to a general quantity. The statistics related to the displacement speed, SDF and the strain rates which influence the evolution of SDF have been evaluated at a given value of the progress variable and then ensemble averaged using samples from different time instants. A similar technique has been used in several previous analyses of freely propagating statistically planar turbulent premixed flames (e.g. Boger et al. 1998; Chakraborty 2007). Note that in the post-processing of displacement speed, SDF and the strain rates which affect the evolution of SDF have been sampled on a given \(x-z\) plane in terms of y/h values as \(y^{+}\) in the case of the reacting channel varies with axial distance due to velocity acceleration caused by thermal expansion effects. The data has been analysed at \(y/h=0.005\) and \(y/h=0.18\) locations corresponding to \(y^{+}=0.6\) and \(y^{+}=20\) respectively. These \(y^{+}\) values have been evaluated based on the friction velocity for the corresponding non-reacting channel flow configuration.

In this configuration, both turbulent kinetic energy \(\widetilde{k}\) and dissipation rate \(\widetilde{\varepsilon }\) remain functions of wall normal distance. For example, turbulent kinetic energy decreases, whereas its dissipation rate increases as the wall is approached. The integral length scale based on \(\widetilde{\varepsilon }\) and \(\widetilde{k}\) can be defined as \(\widetilde{k}^{1.5}/\widetilde{\varepsilon }\) and the root-mean-square velocity as \((2\widetilde{k}/3)^{0.5}\). In the case of wall bounded flows both the integral length scale and the root-mean-square velocity based on the aforementioned definitions decay close to the wall. This implies that Damköhler and Karlovitz numbers (i.e. Da and Ka) can be estimated using turbulent kinetic energy \(\widetilde{k}\) and its dissipation rate \(\widetilde{\varepsilon }\) in the following manner: \(Da=\widetilde{k}S_L/\widetilde{\varepsilon }\delta _{th}\) and \(Ka=\widetilde{\varepsilon }^{0.5}\delta _{th}^{0.5}/S_L^{1.5}\). According to these relations Da decreases as the wall is approached and vanishes at the wall. By contrast, Ka increases towards the wall and assumes the highest value at the wall in the channel flow configuration. However, the integral length scale based on two-point correlations becomes large as the wall is approached for low \(Re_\tau \) boundary layers (Ahmed et al. 2020). This indicates that when the length scale based on two-point correlations is used the Damköhler number assumes infinitely large values, whereas vanishingly small values of Karlovitz number are obtained at the wall. Thus, in this configuration the value of Damköhler number (or Karlovitz number) at a given \(y^+\) or y/h location cannot be evaluated in an unambiguous manner. However, in the current flow configuration away from the wall the values for Damköhler number remain high (i.e. \(Da>>1\)) and Karlovitz number remains small (i.e. \(Ka<<1\)). Thus the flame nominally belongs to the corrugated flamelets regime away from the wall.

4 Results and Discussion

4.1 Mean Flow Behaviour

The non-reacting auxiliary channel flow simulation has been compared with the results of Tsukahara et al. (2005)Footnote 1 at \(Re_{\tau }=110\) and an excellent agreement has been obtained as shown in Fig. 2. It is useful to quantify the flame quenching distance \(\delta _{Q}\) to establish the accuracy of the simulation with the isothermal wall boundary conditions. In this case a quenching Peclet number \(Pe_{Q}=\delta _{Q}/\delta _{z}\) is used (\(\delta _{z}=\alpha _{TR}/S_{L}\) is the Zeldovich flame thickness, where \(\alpha _{TR}\) is the unburned gas thermal diffusivity). Here \(\delta _{Q}\) is taken to be the minimum wall-normal distance of the non-dimensional temperature \(T=0.75\) isosurface (i.e. the value of the temperature isosurface at which the maximum heat release rate is obtained for an unstrained laminar flame for the present thermo-chemistry), where \(T=(\hat{T}-T_{R})/(T_{ad}-T_{R})\) is the non-dimensional temperature and \(\hat{T}\) is the local dimensional temperature at a given point. The minimum Peclet number \(Pe_Q\), which represents the minimum wall normal distance of the flame signifying the flame quenching distance, under isothermal wall conditions is found to be 2.02 which is close to the laminar head-on quenching value of 2.19 and is consistent with earlier studies (Lai and Chakraborty 2016b; Lai et al. 2017b). In the case of fully developed channel flows, as used in this work, the boundary layer extends to the centre of the channel (Pope 2000). Usually the viscous sub-layer region is demarcated by the region showing \(u^+=y^{+}\) behaviour (Pope 2000). For the present flow configuration, the viscous sub-layer region extends up to approximately \(y/h=0.045\), which correspond to about \(y^+=5\) and can be approximated by the \(u^+\)-vs-\(y^{+}\) plot in Fig. 2.

Mean velocity (\(u^{+}=\overline{u}/u_{\tau}\)) and Reynolds stresses in the auxiliary channel flow simulation compared with the earlier DNS of Tsukahara et al. (2005)

Figure 3 shows the Favre averaged progress variable distributions for the two V-flame cases investigated. It can be seen that the flame interacts with the wall further upstream in the case of adiabatic wall conditions while the flame tends to interact with the wall further downstream in the case of an isothermal wall boundary condition. This behaviour of the flame originates due to the differences in the temperature boundary condition at the wall and consequently due to the differences in the reaction rate values at the wall in the two cases investigated. In order to explore this further the data has been extracted at \(x/h=7\) as denoted by the dashed line in Fig. 3.

The behaviours of the mean values of density, and Favre mean values of streamwise velocity, progress variable and non-dimensional temperature are shown in Fig. 4 for the two cases at \(x/h=7\) for the sake of conciseness. Note that some quantitative differences for the mean quantities are observed between different x/h sampling locations in the region where the flame–wall interaction takes place, but qualitatively the results remain similar, as reported for \(x/h=7\). It can be seen from Fig. 4 that the behaviours of mean values of density, and Favre mean values of progress variable and temperature are significantly different for the regions between \(y/h=0\) to \(y/h=0.5\) and the region beyond \(y/h=0.5\). Differences in the mean values of density, and Favre mean values of progress variable and temperature near the bottom wall region (between \(y/h=0\) and \(y/h=0.5\)) can be noticed between the two cases, while the Favre mean stream wise velocity is unaffected by the change in the wall boundary condition. Note that the decoupling between the progress variable and temperature in the isothermal case originates due to quenching as a result of the heat loss at the isothermal walls and this behaviour has implications on how the flame surface evolves under different wall boundary conditions. The decoupling between the progress variable and temperature in the case of isothermal walls is consistent with several previous DNS (Lai and Chakraborty 2016b; Lai et al. 2018b; Ahmed et al. 2018; Alshaalan and Rutland 1998, 2002; Gruber et al. 2010) and experimental investigations (Jainski et al. 2017b, 2018). It is worth noting that boundary conditions for species mass fraction and temperature are different at the isothermal wall. The species mass fraction follows a Neumann boundary condition, whereas a Dirichlet boundary condition is specified for temperature. As a result of flame quenching, the unburned reactants diffuse from the near-wall region and their mass fraction drops at the wall, which leads to an increase in c. This behaviour has been reported in several previous analyses on flame–wall interaction involving both simple (Lai and Chakraborty 2016a, b; Lai et al. 2017a; Sellmann et al. 2017) and detailed (Lai et al. 2018a) chemical mechanisms. Moreover, this behaviour was also reported in previous DNS investigations on V-flame–wall interaction in the case of single-step chemistry by Alshaalan and Rutland (1998, 2002) and detailed chemistry by Gruber et al. (2010). This trend is also shown in the recent experimental results of Jainski et al. (2017b, 2018).

Profiles of normalised mean density, normalised Favre mean streamwise velocity, Favre mean progress variable and Favre mean non-dimensional temperature at \(x/h=7\). Here \(u_{\tau R}\) and \(\rho _R\) are the non-reacting friction velocity at \(Re_{\tau }=110\) and unburned gas density, respectively

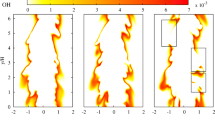

4.2 Mean Behaviour of SDF and Flame Thickness

Figure 5 shows the values of \(|\nabla c|\times \delta _{th}\) conditioned on c at different y/h locations. Note that the peak mean value of \(|\nabla c|\times \delta _{th}\) indicates a tendency towards flame thinning \((>1)\) or thickening \((<1)\) in the mean sense when compared with the freely propagating laminar flame. In both cases the mean peak value of \(|\nabla c|\times \delta _{th}\) increases (thinner flame) as the distance for the wall increases. The results from the turbulent V-flame simulations have also been compared with 2-D V-flames interacting with a fully developed laminar boundary layer in a channel flow configuration with adiabatic and isothermal wall boundary conditions. The non-reacting laminar channel flow has the same centreline mean axial velocity as that of the non-reacting turbulent channel flow simulations. At \(y/h=0.005\), the peak mean value of \(|\nabla c|\times \delta _{th}\) decreases under both wall boundary conditions in both laminar and turbulent conditions (i.e. the flame becomes thicker), with isothermal walls having the lowest peak mean value of \(|\nabla c|\times \delta _{th}\) between the two wall boundary conditions. Note that in the case of adiabatic walls at \(y/h=0.005\) the flame thickness increases more towards the product side of the flame as shown in Fig. 5. Furthermore, smaller peak mean values of the SDF for laminar flames than the corresponding peak mean values for turbulent flames are observed for both wall boundary conditions used in this work. This implies that the turbulent boundary layer tends to promote high values of the SDF.

4.3 Mean Behaviour of Dilatation and Aerodynamic Strain Rates

The changes in the flame thickness at different wall distances can be explained by Eqs. (6)–(8), which provide a means to understand the specific contributions from the statistical behaviours of \(S_{d}\), \(a_{N}\) and \(a_{T}\) to the SDF and its evolution. The mean values of dilatation rate \(\nabla \cdot \mathbf {u}\), normal strain rate \(a_{N}\) and the tangential strain rate \(a_{T}\) conditioned upon c are shown at different y/h locations within and outside the viscous sub-layer in Fig. 6. At \(y/h=0.005\) in the viscous sub-layer region, the magnitudes of the mean values of \(\nabla \cdot \mathbf {u}\) remain smaller than that of \(a_{T}\) and \(a_{N}\) under the two wall boundary conditions considered. This trend changes at \(y/h=0.18\) outside the viscous sub-layer region and the mean values of \(\nabla \cdot \mathbf {u}\) assume greater values in comparison to that of \(a_{T}\) and \(a_{N}\), while the contribution from \(a_{T}\) decreases. Due to the differences in the wall boundary conditions between the two cases the mean values of \(\nabla \cdot \mathbf {u}\) at \(y/h=0.005\) for adiabatic walls are higher than the ones found in the case of isothermal walls. The dilatation rate \(\nabla \cdot \mathbf {u}\) assumes mostly positive values in the case of premixed flames due to heat release and this effect is attenuated in the viscous sub-layer region under adiabatic walls due to constriction of the velocity gradient in the wall normal direction and under isothermal walls due to the heat loss through the cold wall. The mean value of \(a_N\) remains positive outside the viscous sub-layer region at \(y/h=0.18\) for all the cases, whereas inside the viscous sub-layer it assumes negative values for the turbulent cases, as shown in Fig. 6. In the case of laminar flow, the variation of normal strain rate \(a_N\) conditional upon c away from the wall is qualitatively similar to that under turbulent flow conditions.

The strain rate \(a_{N}\) can be expressed as \(a_{N}=(e_{\alpha }{{\cos }}^{2}\theta _{\alpha } +e_{\beta }{{\cos }}^{2}\theta _{\beta } +e_{\gamma }{{\cos }}^{2}\theta _{\gamma })\), where \(e_{\alpha }\), \(e_{\beta }\) and \(e_{\gamma }\) are the most extensive, intermediate and most compressive principal strain rates respectively, and \(\theta _{\alpha }\), \(\theta _{\beta }\) and \(\theta _{\gamma }\) are the angles between \(\nabla c\) and the eigenvectors associated with \(e_{\alpha }\), \(e_{\beta }\) and \(e_{\gamma }\) respectively. It is well known that \(\nabla c\) aligns with the eigenvector associated with \(e_{\alpha }\) when the strain rate due to flame normal acceleration dominates over turbulent straining, and this is highly probable for flames with high Damköhler number (i.e. \(Da>1\)) (Kim and Pitsch 2007; Ahmed et al. 2014; Chakraborty and Swaminathan 2007). By contrast, \(\nabla c\) preferentially aligns with the eigenvector associated with \(e_{\gamma }\) when turbulent strain rate overcomes the strain rate arising from flame normal acceleration, which is highly probable for \(Da<1\) (Kim and Pitsch 2007; Ahmed et al. 2014; Chakraborty and Swaminathan 2007).

Profiles of the mean values of \(e_{\alpha }{{\cos }}^{2}\theta _{\alpha }\), \(e_{\beta }{{\cos }}^{2}\theta _{\beta }\), \(e_{\gamma }{{\cos }}^{2}\theta _{\gamma }\) (normalised by \(\delta _{th}\)/\(S_{L}\)) conditioned upon c at different distances away from the wall. The lines with symbols represent the laminar V-flame results

In the current case, Da remains greater than unity throughout the flame away from the wall, as \(Re_{\tau }\) for the channel flow is low resulting in a large integral length scale and low velocity fluctuations (Ahmed et al. 2020) when compared with \(\delta _{th}\) and \(S_{L}\), and this gives rise to preferential alignment between \(\nabla c\) and the eigenvector in the principal direction corresponding to \(e_{\alpha }\) away from the wall for both isothermal and adiabatic boundary conditions. This can be substantiated from higher mean values of \(e_\alpha {{\cos }}^2 \theta _\alpha \) than that of \(e_\gamma cos^2 \theta _\gamma \) at \(y/h=0.18\) in Fig. 7 where the profiles of the mean values of \(e_\alpha {{\cos }}^2 \theta _\alpha \), \(e_\beta {{\cos }}^2 \theta _\beta \) and \(e_\gamma {{\cos }}^2 \theta _\gamma \) conditional upon c are shown at \(y/h=0.005\) and 0.18. However, the strain rate arising from flame normal acceleration remains low in the viscous sub-layer region (e.g. \(y/h=0.005\)) for turbulent conditions due to the low temperature at the wall under isothermal conditions and due to the constriction of the velocity gradients in the wall normal direction under both adiabatic and isothermal wall boundary conditions. This consequently leads to \(\nabla c\) aligning with the eigenvector associated with \(e_{\gamma }\) giving rise to negative mean values of \(a_{N}\) in the near-wall region under turbulent conditions as shown in Fig. 6, and this can be substantiated from higher mean values of \(e_\gamma {{\cos }}^2 \theta _\gamma \) than that of \(e_\alpha {{\cos }}^2 \theta _\alpha \) at \(y/h=0.005\) in Fig. 7. In contrast, under the laminar conditions \(\nabla c\) aligns with the eigenvector associated with \(e_{\alpha }\) and consequently \(a_{N}\) assumes positive values at all locations for isothermal boundary conditions and only in the unburned gas side (e.g. \(c<0.2\)) in the case of adiabatic boundary condition. In order to explain this behaviour the contours of c in the near-wall region for both adiabatic and isothermal boundary conditions are shown in Fig. 8. In purely 2D flow the normal strain rate \(a_N\) is given by \(a_N=N_1^2\partial u_1/\partial x_1 +N_1N_2\partial u_1/\partial x_2 +N_1N_2\partial u_2/\partial x_1+N^2_2\partial u_2/\partial x_2\). In the laminar V-flame case with isothermal boundary condition, the contours of c almost obliquely intersect the wall without much bending (see Fig. 8). Under these conditions, \(N_1^2\partial u_1/\partial x_1\) and \(N_1N_2\partial u_1/\partial x_2\) remain positive (because \(\partial u_1/\partial x_1\) is positive for thermal expansion and \(\partial u_1/\partial x_2\) is positive in the laminar boundary layer with \(N_1N_2\) being positive) and dominant to yield positive values of \(a_N\) in the case of laminar V-flame, which can be seen from the higher values of \(e_{\alpha }{{\cos }}^{2}\theta _{\alpha }\) than \(e_{\gamma }{{\cos }}^{2}\theta _{\gamma }\) in the near wall region (e.g. \(y/h=0.005\) in Fig. 7). In the case of laminar adiabatic boundary condition, the contours of \(c<0.2\) remain mostly straight and intersect the wall without much bending towards the unburned gas side (see Fig. 7) and therefore the normal strain rate \(a_N\) and its components \(e_{\alpha }{{\cos }}^{2}\theta _{\alpha }\) and \(e_{\gamma }{{\cos }}^{2}\theta _{\gamma }\) behave qualitatively similarly to the isothermal wall condition due to the aforementioned reasons. However, the contours of c become significantly curved before intersecting with the wall for \(c>0.2\) in the case of laminar V-flame under adiabatic wall condition and this leads to negative values of \(a_N\) (i.e. \(\partial u_1/\partial x_1\) and \(N_1N_2\) can be negative for curved c contours). The flame normal acceleration towards the wall across the curved flame elements in the adiabatic laminar V-flame case induces a compressive strain rate in the near-wall region because of the impenetrable nature of the wall. These mechanisms are reflected in the higher values of \(e_{\gamma }{{\cos }}^{2}\theta _{\gamma }\) than \(e_{\alpha }{{\cos }}^{2}\theta _{\alpha }\) in the region corresponding to \(c>0.2\) for \(y/h=0.005\) in the case of laminar V-flame with adiabatic walls. From the expression in Eq. (6) it can be deduced that in turbulent flames in the regions outside the viscous sub-layer, the normal flow strain has a net flame thickening effect whereas inside the viscous sub-layer region it has a flame thinning effect. In the case of laminar flames, in the viscous sub-layer region, the normal flow strain has a net flame thinning effect for the adiabatic wall boundary condition and a net thickening effect for isothermal wall boundary conditions.

The influence of the velocity gradients on the flame surface area can be determined by examining the behaviour of \(a_{T}\). The mean value of \(a_{T}=\nabla \cdot \mathbf{{u}}-a_{N}\) is determined by the relative magnitudes and signs of \(\nabla \cdot \mathbf {u}\) and \(a_{N}\). In the viscous sub-layer region (e.g. \(y/h=0.005\)) under turbulent conditions the large negative mean value of \(a_{N}\) and a small mean positive value of \(\nabla \cdot \mathbf {u}\) leads to a large positive mean value of \(a_{T}\) for both wall boundary conditions. Whereas, under laminar conditions for isothermal walls the large positive values of \(a_{N}\) and \(\nabla \cdot \mathbf{{u}}=0\) lead to large negative values of \(a_{T}\). In the case of adiabatic walls, under laminar conditions, the value of \(a_{T}\) varies from negative at the front of the flame to positive at the rear of the flame. This is due to the small positive values of \(\nabla \cdot \mathbf {u}\) and large variations of \(a_{N}\) across the flame. According to Eq. (8) this implies that under turbulent conditions the aerodynamic tangential strain acts to increase flame surface area in the viscous sub-layer region. Outside the viscous sub-layer (e.g. \(y/h=0.18\)) the mean values of \(\nabla \cdot \mathbf {u}\) and \(a_{N}\) remain close to each other thus yielding a small positive mean value of \(a_{T}\) in both cases. This can be established further by examining the instantaneous \(c=0.5\) isosurface for the bottom branch of the flame as shown in Figs. 9, 10 and 11. The dilatation rate \(\nabla \cdot \mathbf{{u}}=a_{T}+a_{N}\) is vanishingly small close to the wall in the isothermal case due to the heat loss at the wall. By contrast, in the case of the adiabatic wall, \(\nabla \cdot \mathbf {u}\) remains non-zero but very small in the vicinity of the wall due do the constriction of the velocity gradients in the wall normal direction. It can be seen in Figs. 9, 10 and 11 that both flames curve in the upstream direction in the near wall region, but the adiabatic case tends to curve more than the isothermal case, which explains the variation of \(a_{T}\) and \(a_{N}\) statistics between the two cases in the near wall region.

4.4 Mean Behaviour of Displacement Speed

Profiles of the mean values of reaction rate and different components of the diffusion rate (normalised by \(\rho _{R}\), \(S_{L}\) and \(\delta _{th}\)) conditioned upon c. The solid lines represent the respective V-flame cases and the dashed lines represent the freely propagating laminar flame results. The lines with symbols represent the laminar V-flame results

The behaviour of the flame in the near wall region is further investigated by analysing the statistics of flame displacement speed and its components as expressed in Eqs. (4)–(5). The mean values of individual contributions of the components and the total displacement speed for both laminar and turbulent conditions are shown in Fig. 12 for both wall boundary conditions in the viscous sub-layer and the log-layer region of the boundary layer. The mean values of \(S_{d}\) and its constituent components are identical outside the viscous sub-layer at \(y/h=0.18\) for adiabatic and isothermal walls under both laminar and turbulent conditions and are consistent with the values obtained for the freely propagating flame in the top part of the channel (i.e. the flame in the region \(y/h>1\)). These results are also consistent with the earlier findings from simple chemistry (Chakraborty 2007; Chakraborty and Cant 2005a, b; Chakraborty and Klein 2008) and detailed chemistry DNS (Chen and Im 1998; Echekki and Chen 1996, 1999; Peters et al. 1998) of statistically planar turbulent premixed flames. Notable differences in the mean behaviour of \(S_{d}\) and its components can be seen between the two wall boundary conditions in the viscous sub-layer region at \(y/h=0.005\). In the turbulent case with isothermal walls, the mean displacement speed in the near wall region is driven by the diffusion processes (i.e. \(S_{t}\) and \(S_{n}\)) and the mean value of \(S_{d}\) is negative in some parts of the flame. This implies that the flame is retreating in the burned gas due to the heat loss through the cold wall. In the case of adiabatic walls, the mean value of \(S_{d}\) remains positive and all the components of the displacement speed play important roles in controlling the mean value of \(S_{d}\). It should be noted that the mean value of \(S_{d}\) is much lower for the flames with adiabatic walls at \(y/h=0.005\) when compared with the values at \(y/h=0.18\). Furthermore, the mean values of \(S_d\) tend to decrease towards the product side of the flame and assume a plateau, which implies that the flame is slowing down in the near wall region, because for a freely propagating flame \(S_d\) increases with reaction progress variable c. This can further be verified by examining the mean contributions of the reaction rate (\(\dot{\omega }_{c}\)), tangential (\(-2\rho \alpha _{c} \kappa _{m}\left| \nabla c\right| \)), normal (\(\varvec{N}\cdot \nabla (\rho \alpha _{c} \varvec{N} \cdot \nabla c)\)) and total diffusion rate (\(\nabla \cdot (\rho \alpha _{c} \nabla c)\)) in Eq. (2) conditioned upon c, which are shown in Fig. 13 for both wall boundary conditions at the different wall distances. The approximate reaction-diffusion balance holds in all cases outside the viscous sub-layer region at \(y/h=0.18\), but in the viscous sub-layer region (e.g. \(y/h=0.005\)) the reaction rate is zero for isothermal wall conditions. The diffusion rates do not vanish in the viscous sub-layer region for cases with isothermal walls and exhibit small mean values close to the wall. By contrast, the mean contributions of both reaction and diffusion processes remain significant in the viscous sub-layer region in cases with adiabatic walls. In both cases, outside the viscous sub-layer (i.e. \(y/h=0.18\)), the reaction-diffusion balance is almost identical to that of a freely propagating laminar flame, while significant differences exist between the freely propagating laminar flame and the V-flame results in the viscous sub-layer region.

It should be recognised here that the theory of stretched flames by the pioneering work of Matalon and Matkowsky (1982) and Candel and Poinsot (1990) has been developed based on simplified assumptions without referring to detailed chemistry and transport. The displacement speed statistics from simple chemistry (e.g. Chakraborty 2007; Chakraborty and Cant 2004, 2005b) and detailed chemistry DNS (e.g. Echekki and Chen 1996, 1999) are qualitatively similar. The stretch rate dependence of displacement speed from simple chemistry DNS (Chakraborty et al. 2007) has been found to be qualitatively similar to the detailed chemistry results by Chen and Im (1998). The value corresponding to the maximum reaction rate at different wall normal locations can be seen from Fig. 13. In the context of single step chemistry, the reaction rate is a function of c and T, thus this term responds to heat loss and the inequality between c and T in the vicinity of the wall, and this behaviour can be seen for the isothermal wall case. The combustion conditions nominally belong to the corrugated flamelets regime away from the wall for the cases considered here and under such a condition (as shown later the mean stretch rate remains weak) it is expected that the mean values of reaction rate and molecular diffusion rate conditional on c will not change significantly.

4.5 Mean Behaviour of the Strain Rates Due to Flame Propagation

The changes in the behaviour of displacement speed have strong implications on the evolution of the flame surface. This can be further investigated by examining Eq. (7). The mean values of \(N_{j}\partial S_{d}/\partial x_{j}\) normalised by \(\delta _{th}/S_{L}\), conditioned on c at different y/h locations under both wall boundary conditions are shown in Fig. 14. The mean value of \(N_{j}\partial S_{d}/\partial x_{j}\) is dominated by \(N_{j}\partial (S_{r}+S_{n})/\partial x_{j}\), while the effect of \(N_{j}\partial S_{t}/\partial x_{j}\) is negligible outside the viscous sub-layer region (e.g. \(y/h=0.18\)) for both cases. This is consistent with the expected behaviour in the corrugated flamelets regime combustion, which prevails away from the wall, where the component arising from kinematic restoration (i.e. \(N_j\partial (S_r+S_n)/\partial x_j\)) dominates over the curvature contribution (i.e. \(N_j\partial S_t/\partial x_j\)) of the additional strain rate induced by flame propagation. In contrast, within the viscous sub-layer, there is a competition between \(N_{j}\partial (S_{r}+S_{n})/\partial x_{j}\) and \(N_{j}\partial S_{t}/\partial x_{j}\) for cases with adiabatic walls, as the chemical reaction rate is sustained at the wall. However, for isothermal wall boundaries under both laminar and turbulent conditions, the mean \(N_{j}\partial (S_{r}+S_{n})/\partial x_{j}\) contributions to \(N_{j}\partial S_{d}/\partial x_{j}\) are small in comparison to that of \(N_{j}\partial S_{t}/\partial x_{j}\) due to the existence of the cold wall and a drop in the reaction rate. In the case of laminar flame with isothermal walls \(N_{j}\partial S_{d}/\partial x_{j}\) shows much smaller magnitude than the corresponding mean values in the turbulent flame in the near wall region (e.g. \(y/h=0.005\)) as the contributions from kinematic restoration and curvature are small in magnitude in the case of the laminar V-flame. This behaviour originates due to the fact that at a given wall normal location the flame is at the same stage of quenching in the 2D laminar V-flame under isothermal wall boundary condition, whereas turbulent flamelets at a given wall normal distance show various extents of chemical activities (e.g. heat release rate and thermal expansion) even under isothermal boundary condition as a result of flame wrinkling under turbulent fluid motion. In both boundary conditions, under turbulent conditions, within the viscous sub-layer \(N_{j}\partial S_{d}/\partial x_{j}\) assumes higher mean values (and the mean value is positive) when compared with those outside the viscous sub-layer region, which promotes small values of \(|\nabla c|\) as evident from Fig. 5. Small negative mean values of \(N_{j}\partial S_{d}/\partial x_{j}\) at \(y/h=0.18\) can be observed for both boundary conditions which tends to promote high values of \(|\nabla c|\) and can be confirmed from Fig. 5 at \(y/h=0.18\).

Figure 15 shows the mean behaviour of the flame propagation effect associated with the curvature stretch \(2S_{d}\kappa _{m}\), the last term in Eq. (6) and its constituent components for both wall boundary conditions. Note that the mean values of \(2S_{d}\kappa _{m}\) and its components remain weakly negative and very close to zero outside the viscous sub-layer region at \(y/h=0.18\) under both wall boundary conditions. The correlation between \((S_r+S_n)\) and \(\kappa _m\) and the deterministic negative values of \(S_t\kappa _m=-4D\kappa _m^2\) are responsible for negative mean values of \(2S_d\kappa _m\). In the viscous sub-layer region for adiabatic wall conditions, both \(2(S_{r}+S_{n})\kappa _{m}\) and \(2S_{t}\kappa _{m}\) assume negative value towards the unburned gas side of the flame and progressively diverge towards the trailing edge of the flame leading to a competition between \(2(S_{r}+S_{n})\kappa _{m}\) and \(2S_{t}\kappa _{m}\). This is caused by the existence of the adiabatic wall boundary condition which leads to no heat loss at the wall and consequently leading to reaction on the wall surface. In contrast, \(2S_{d}\kappa _{m}\) and its components remain close to zero or negative under isothermal wall conditions within the viscous sub-layer region due to the heat loss at the wall which leads to quenching of the flame.

4.6 Mean Behaviour of Effective Normal and Tangential Strain Rates

The mean values of \(a^{eff}_{N}\) conditioned on c for both wall boundary conditions at different y/h locations are shown in Fig. 16. Under turbulent conditions with adiabatic walls in the viscous sub-layer (e.g. \(y/h=0.005\)), the mean effective normal strain rate assumes both positive and negative values within the flame-front, whereas in the turbulent case with isothermal walls, the mean value of \(a^{eff}_{N}\) remains positive throughout the flame at this location. A comparison between Figs. 5 and 16 reveals that the negative mean \(a^{eff}_{N}\) in the case with adiabatic walls at \(y/h=0.005\) occurs at the same c values where flame thinning is observed, by contrast the positive mean \(a^{eff}_{N}\) occurs for c values at which the flame thickens in both cases. This is in contrast to the laminar conditions, where \(a^{eff}_{N}\) is weakly negative or has zero contributions. Outside the viscous sub-layer (e.g. \(y/h=0.18\)) the mean value of \(a^{eff}_{N}\) for the turbulent cases remains weakly positive or very close to zero and a very small amount of flame thinning can be observed at this location under both wall boundary conditions as shown in Figs. 5 and 16. It is important to note that the statistical behaviour of the SDF at a given wall normal distance in the laminar V-flame case under isothermal wall boundary condition is fundamentally different from the corresponding turbulent flame case. At a given wall normal distance the laminar V-flame case shows a unique value of reaction rate, heat release and dilatation rate, whereas these values change in the homogeneous spanwise direction for the turbulent V-flame case because flame elements show a range of c, reaction rate and molecular diffusion rate values due to flame wrinkling. Therefore, even though the near-wall dynamics of the SDF is expected to be driven by convection-diffusion mechanisms in the isothermal case, due to flame quenching, these behaviours are different between laminar and turbulent flame cases at a given wall normal distance because of the differences in thermal expansion and molecular diffusion characteristics.

Figure 16 also shows the mean values of \(a^{eff}_{T}\) conditioned on c for both wall boundary conditions at different y/h locations. A positive (negative) value of \(a^{eff}_{T}\) is indicative of flame area generation (destruction). The mean value of \(a^{eff}_{T}\) remains close to zero outside the viscous sub-layer (e.g. \(y/h=0.18\)) for both wall boundary conditions. Within the viscous sub-layer region (e.g. \(y/h=0.005\)), for adiabatic wall boundary condition, the mean value of \(a^{eff}_{T}\) is negative at the front of the flame before assuming positive values for the rest of the flame under both laminar and turbulent conditions. In the case of isothermal walls under both laminar and turbulent conditions, within the viscous sub-layer region, the mean value of \(a^{eff}_{T}\) remains mostly negative. This implies that the flame surface is generated for adiabatic walls due to a non-zero reaction in the viscous sub-layer region, whereas the flame is quenched by the isothermal cold wall leading to a much flatter flame and lower flame surface area.

4.7 Modelling Implications

It can be seen from Fig. 12 that the mean values of \(S_{d}\) in the turbulent cases decrease in the viscous sub-layer region not only for isothermal wall boundary conditions due to local flame quenching caused by wall heat loss, but also for adiabatic wall boundary conditions. Although it is not shown here explicitly, similar qualitative conclusions can be drawn for the density-weighted displacement speed \(\rho S_{d}\). Furthermore, the mean value of \(|\nabla c|\) also decreases in the viscous sub-layer region for both cases (see Fig. 5) due to the mechanisms described earlier, although this tendency is particularly strong for the case with isothermal walls due to flame quenching. This suggests that the mean value of \(\rho S_{d}|\nabla c|=\dot{\omega }_{c}+\nabla \cdot (\rho \alpha _{c}\nabla c)\) decreases in the near wall region for both wall boundary conditions, which can be substantiated from Fig. 13. The flame quenching is responsible for the small mean value of \(\rho S_{d}|\nabla c|=\dot{\omega }_{c}+\nabla \cdot (\rho \alpha _{c}\nabla c)\) in the viscous sub-layer region in the case of isothermal walls, whereas in the case with adiabatic walls, the profile of the normal diffusion component \({\varvec{N}}\cdot \nabla (\rho \alpha _{c}{\varvec{N}}\cdot \nabla c)\) changes in the viscous sub-layer region in comparison to that for the freely-propagating planar laminar premixed flame (as shown in Fig. 13) as a result of the zero wall-normal gradient of c. Furthermore, the interaction of the flame elements with near wall vortical structures stretch the flame elements in such a manner in the case with adiabatic walls that a predominance of positive curvature (i.e. flame element convex to the reactants) is observed at \(y/h=0.005\) (or \(y^{+}=0.6\)), which leads to a negative mean value of the tangential diffusion rate \((-2\rho \alpha _{c}\kappa _{m}|\nabla c|)\) at this location. The predominance of positive curvature in the viscous sub-layer region can be confirmed by Fig. 17 which shows the \(c=0.5\) isosurface between \(y^{+}\) of 0 and 6 coloured by \(\kappa _{m}\times \delta _{th}\) for both cases. The changes in the statistical behaviours of \({\varvec{N}}\cdot \nabla (\rho \alpha _{c}{\varvec{N}}\cdot \nabla c)\) and \(-2\rho \alpha _{c}\kappa _{m}|\nabla c|\) in the viscous sub-layer region, when compared with those in the freely-propagating flames, lead to the reduction in \(\rho S_{d}|\nabla c|\) at \(y^{+}=0.6\) in the case with adiabatic walls.

On Reynolds averaging \(\rho S_{d}|\nabla c|\) one obtains \(\overline{(\rho S_{d})}_{s}\Sigma _{gen}=\overline{\dot{\omega } _c}\) (as \(\overline{\nabla \cdot (\rho \alpha _{c}\nabla c)}\) \(<<\overline{\dot{\omega }}_c\) in the context of Reynolds Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) simulations) where \(\Sigma _{gen}=\overline{|\nabla c|}\) is the generalised FSD and \(\overline{(Q)}_{s}=\overline{Q|\nabla c|}/\Sigma _{gen}\) is the surface-averaging operation for a general quantity Q (Boger et al. 1998; Trouvé and Poinsot 1994). The decreasing trend of \(\rho S_d|\nabla c|\) in the vicinity of the wall suggests that \(\overline{\dot{\omega }}_c\) is expected to decrease in the near-wall region for the case with adiabatic walls, whereas \(\overline{\dot{\omega }}_c\) vanishes at the wall in the case with isothermal walls due to flame quenching caused by the cold wall. This can be substantiated from Fig. 18 which reveals that the mean reaction rate away from the bottom wall at \(x/h=7\) is almost identical in both wall boundary conditions, but a significant difference can be observed between the two cases near the bottom wall. In the case with adiabatic walls, a significant reduction in the mean reaction rate can be seen near the bottom wall but the mean reaction rate remains non-zero, while in the case with isothermal walls the reaction rate goes to zero at the wall. In the case with adiabatic walls, one obtains \(\widetilde{c}=0.62\) and \(\overline{\dot{\omega }}_c\times \delta _{th}/\rho _{R}S_{L}=0.05\) at the wall, whereas for the flame branch in the top half of the channel (i.e. \(y/h>1\)) one obtains \(\overline{\dot{\omega }}_c\times \delta _{th}/\rho _{R}S_{L}=0.13\) for \(\widetilde{c}=0.62\). This behaviour has implications on the mean reaction rate closure in the viscous sub-layer region of the flow.

Profiles of the mean reaction rates from DNS of turbulent V-flames (left) evaluated from \(\Sigma \) (middle) and \(\widetilde{\epsilon }_{c}\) (right) at \(x/h=7\). The vertical dotted line for \(\overline{\dot{\omega }}_{c}\) plot on the left shows the mean reaction rate at the same value of \(\widetilde{c}\) for the top branch of the flame as the value of \(\widetilde{c}\) at the bottom wall for the case with adiabatic wall boundary conditions. Case-A and Case-B imply the turbulent V-flame simulations with adiabatic and isothermal wall boundary conditions respectively

Often \(\overline{(\rho S_{d})}_s\) is approximated as \(\overline{(\rho S_{d})}_s=\rho _{R}S_{L}\) (Boger et al. 1998; Hawkes and Cant 2001) and thus the FSD based reaction rate closure takes the form \(\overline{\dot{\omega }}_c=\rho _{R}S_{L}\Sigma _{gen}\) in the context of RANS, whereas \(\overline{\dot{\omega }}_c\) can alternatively be closed via the scalar dissipation rate \(\widetilde{\epsilon }_c=\overline{\rho \alpha _{c}\nabla c\cdot \nabla c}/\overline{\rho }-\widetilde{\alpha }_c\nabla \widetilde{c}\cdot \nabla \widetilde{c}\) in the following manner \(\overline{\dot{\omega }}_c=2\overline{\rho }\widetilde{\epsilon }_c/(2C_m-1)\) (Bray 1979; Chakraborty et al. 2011), where \(C_m\) is a thermo-chemical parameter which takes a value of 0.78 for the present thermo-chemistry. It can be seen from Fig. 18 that in both cases \(\rho _{R} S_{L}\Sigma _{gen}\) and \(2\overline{\rho }\widetilde{\epsilon }_c/(2C_m-1)\) decrease at the bottom wall, but higher values of \(2\overline{\rho }\widetilde{\epsilon }_c/(2C_m-1)\) can be seen in the vicinity of the wall for the case with adiabatic walls when compared with the case with isothermal walls. It should be noted here that the mean reaction rate closures based on FSD (i.e. \(\overline{\dot{\omega }}_c=\rho _{R}S_{L}\Sigma _{gen}\)) and SDR (i.e. \( \overline{\dot{\omega }}_c=2\overline{\rho }\widetilde{\epsilon }_c/(2C_m-1)\)) are able to capture the mean reaction rate \(\overline{\dot{\omega }}_c \) trends in the case with adiabatic walls but predict a non-zero mean reaction rate at the wall for the case with isothermal walls. These closures need to be modified for isothermal conditions considered in this work, as the existing closures in the literature lead to high reaction rate predictions in the near wall regions due to high \(\rho _{R}S_{L} \Sigma _{gen}\) and \(\overline{\rho }\widetilde{\epsilon }_c\) values near the bottom wall as shown in Fig. 18. Although the discrepancy between \(\overline{\dot{\omega }}_c\) and \(\rho _{R}S_{L}\Sigma _{gen}\) (or between \(\overline{\dot{\omega }}_c\) and \(2\overline{\rho }\widetilde{\epsilon }_c/(2C_m-1)\)) in the case with adiabatic walls is much smaller than in the case with isothermal walls, there are still differences between \(\overline{\dot{\omega }}_c\) and \(\rho _{R}S_{L}\Sigma _{gen}\) (or between \(\overline{\dot{\omega }}_c\) and \(2\overline{\rho }\widetilde{\epsilon }_c/(2C_m-1)\)) in the viscous sub-layer region for the case with adiabatic walls. This suggests that both FSD and SDR based reaction rate closures need modification in the vicinity of the wall even in the case of adiabatic wall boundary conditions. Near wall modifications to the FSD based mean reaction rate closures have been proposed for wall-induced flame quenching in the past under constant density conditions in the case of turbulent channel flow (Bruneaux et al. 1997) and under variable density conditions in the case of turbulent head-on quenching (Sellmann et al. 2017), but the discrepancy between \(\overline{\dot{\omega }}_c\) and \(\rho _{R}S_{L}\Sigma _{gen}\) for adiabatic wall boundary conditions in the near wall region suggests that the FSD based mean reaction rate closure without flame quenching also needs modification in the viscous sub-layer region and the approximation \(\overline{(\rho S_{d})}_s=\rho _{R}S_{L}\) may not be valid in the viscous sub-layer region. Note that the approximation \(\overline{(\rho S_{d})}_s=\rho _{R}S_{L}\) holds reasonably well away from the wall for weakly stretched flames such as the ones considered in this work, and this can be verified by the good agreement between \(\overline{\dot{\omega }}_c\) from the DNS and \(\rho _{R}S_L\Sigma _{gen}\) when the flame is away from the wall i.e. in the region \(y/h\ge 0.5\). Furthermore, the mean reaction rate closure for SDR (i.e. \(\overline{\dot{\omega }}_c=2\overline{\rho }\widetilde{\epsilon }_c/(2C_m-1)\)) is not flame speed dependant and is also shown to be inadequate in the near-wall region for the isothermal and adiabatic wall boundary conditions. Although near-wall modifications to the SDR based mean reaction rate closure have been proposed earlier for head-on quenching under isothermal wall boundary condition (Lai and Chakraborty 2016b), these will not be valid for flows with boundary layers and adiabatic wall boundary conditions. The expression \(2\overline{\rho }\widetilde{\epsilon }_c/(2C_m-1)\) does not account for the behaviour of the alternation of reaction-diffusion balance explicitly in the viscous sub-layer region under adiabatic wall boundary condition. Hence, it is perhaps expected that the conventional SDR based mean reaction rate closure may not be adequate in the viscous sub-layer region of the reacting flow boundary layer. Furthermore, in reality, the real temperature at the wall will probably lie somewhere in between isothermal and adiabatic conditions which should be considered as limiting cases and probably strongly depends on the specific application. It should be recognised here that in a LES calculation of wall bounded flows the \(y^{+}\) value is usually of the order of 0.6, as shown in many previous investigations for non-reacting (Afgan et al. 2011; Ahmed et al. 2020; Flageul et al. 2019; Hinterberger et al. 2008) and reacting flows (Endres and Sattelmayer 2018; Han and Morgans 2015; Heinrich et al. 2018). Furthermore, similar techniques have been employed in the case of RANS calculations when using the low Reynolds number models (Ahmed and Prosser 2016; Klein et al. 2015; Launder and Sharma 1974). In the case when the value of \(y^{+}\) is considerably higher than 1, the near wall physics needs to be accounted for by the wall functions or the so called near wall treatment of turbulence and combustion. Near wall modelling of \(\overline{\dot{\omega }}_c\) using \(\Sigma _{gen}\) and \(\widetilde{\epsilon }_c\) for both isothermal and adiabatic wall boundary conditions is beyond the scope of the current work but will form part of the future investigations.

5 Summary and Conclusions

Direct numerical simulations (DNS) for two different turbulent V-flames interacting with chemically inert walls in a fully developed turbulent channel flow have been performed at a friction velocity based Reynolds number \(Re_{\tau }=110\) under adiabatic and isothermal wall boundary conditions. Mean quantities such as density, axial velocity, temperature and progress variable have been investigated. It is found that the location at which the oblique flame–wall interaction occurs is affected by the choice of the wall boundary condition. In order to investigate the aforementioned behaviour further the mean behaviours of the surface density function (SDF) (\(|\nabla c|\)) and the strain rates affecting the \(|\nabla c|\) transport have been analysed. The behaviour of SDF is significantly affected by the changes in the wall boundary conditions within the viscous sub-layer region. It is found that the dilatation rate effects weaken in the viscous sub-layer region in the case with adiabatic wall boundary condition due to the constriction of the velocity gradients in the wall normal direction and also due to the existence of the cold wall in the case of isothermal wall boundary condition. Consequently the alignment of \(\nabla c\) with the most extensive (compressive) principal strain rate strengthens (weakens) as the distance from the wall increases. This leads to the differences in the behaviour of normal and tangential strain rates inside and outside of the viscous sub-layer region. The mean behaviours of displacement speed have also been investigated and it is found that in both cases the mean displacement speed decreases in the viscous sub-layer region, but remains positive in the case of adiabatic wall boundary condition, whereas in the case of isothermal wall boundary condition the mean displacement speed has been found to be negative in some parts of the flame. This consequently leads to differences in the normal strain rate arising from flame propagation and the curvature stretch under different wall boundary conditions. It should be noted here that the underlying turbulence and the choice of the wall boundary condition (i.e. adiabatic or isothermal) have significant influences on the flame dynamics in the viscous sub-layer region, but outside the viscous sub-layer region these statistics are not significantly affected. The sensitivity of the statistics of SDF to the choice of the wall boundary conditions and the distance from the wall suggests that the sub-models of the flame surface density or scalar dissipation rate transport need to accurately capture the respective behaviours of the unclosed terms under these conditions.

It can be seen from the transport equation for the SDF that this quantity depends mainly on the statistics of fluid velocity/vorticity, scalar gradient and displacement speed. Previous studies have demonstrated that the displacement speed statistics from simple chemistry (Chakraborty and Cant 2004, 2005b; Chakraborty 2007; Chakraborty et al. 2007, 2011) and detailed chemistry (Echekki and Chen 1996, 1999; Peters et al. 1998; Chen and Im 1998) DNS are qualitatively similar. The same is true for the statistics of the reactive scalar gradient obtained from simple chemistry (Chakraborty and Cant 2005b; Chakraborty and Klein 2008, 2009; Chakraborty et al. 2013) and detailed chemistry DNS studies (Chakraborty et al. 2008, 2013, 2019). Moreover, it has previously been shown that several models developed based on simple chemistry data (Gao et al. 2014; Lai and Chakraborty 2016b) have been found to perform equally well in the context of detailed chemistry and transport in a priori (Lai et al. 2018a; Gao et al. 2016) and a posteriori (Ahmed and Prosser 2016, 2018) assessments. Thus, it can be expected that the findings of this work will at least be qualitatively valid in the presence of detailed chemistry and transport. However, in the presence of detailed chemistry, different choices of reaction progress variable may give rise to different statistical behaviours of the corresponding SDF (Chakraborty et al. 2018) in the vicinity of the wall. It should be recognised here that the effects due to the variation of Lewis number, variations in the wall temperature and high Reynolds number will play a role in determining the SDF statistics during FWI. This along with the utilisation of the near wall SDF statistics to improve the FSD and SDR based reaction rate closures in the vicinity of the wall will form the basis of future investigations.

Notes

Database available online at: https://www.rs.tus.ac.jp/t2lab/db/.

References

Afgan, I., Kahil, Y., Benhamadouche, S., Sagaut, P.: Large eddy simulation of the flow around single and two side-by-side cylinders at subcritical Reynolds numbers. Phys. Fluids 23(7), 075101 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3596267

Ahmed, U., Prosser, R.: Modelling flame turbulence interaction in RANS simulation of premixed turbulent combustion. Combust. Theory Model. 20(1), 34–57 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1080/13647830.2015.1115130

Ahmed, U., Prosser, R.: A posteriori assessment of algebraic scalar dissipation models for RANS simulation of premixed turbulent combustion. Flow Turbul. Combust. 100(1), 39–73 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10494-017-9824-z

Ahmed, U., Prosser, R., Revell, A.J.: Towards the development of an evolution equation for flame turbulence interaction in premixed turbulent combustion. Flow Turbul. Combust. 93(4), 637–663 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10494-014-9557-1

Ahmed, U., Doan, N.A.K., Lai, J., Klein, M., Chakraborty, N., Swaminathan, N.: Multiscale analysis of head-on quenching premixed turbulent flames. Phys. Fluids 30(10), 105102 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5047061

Ahmed, U., Pillai, A.L., Chakraborty, N., Kurose, R.: Statistical behavior of turbulent kinetic energy transport in boundary layer flashback of hydrogen-rich premixed combustion. Phys. Rev. Fluids 4(10), 103201 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevFluids.4.103201

Ahmed, U., Apsley, D.D., Stallard, T., Stansby, P.K., Afgan, I.: Turbulent length scales and budgets of Reynolds stress-transport for open-channel flows; friction Reynolds numbers (Re\(\tau \) ) = 150, 400 and 1020. J. Hydraul. Res. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/00221686.2020.1729265.

Alshaalan, T.M., Rutland, C.J.: Turbulence, scalar transport, and reaction rates in flame-wall interaction. Proc. Combust. Inst. 27(1), 793–799 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0082-0784(98)80474-8

Alshaalan, T.M., Rutland, C.J.: Wall heat flux in turbulent premixed reacting flow. Combust. Sci. Technol. 174(1), 135–165 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1080/713712913

Aspden, A.J., Day, M.S., Bell, J.B.: Three-dimensional direct numerical simulation of turbulent lean premixed methane combustion with detailed kinetics. Combust. Flame 166, 266–283 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2016.01.027

Boger, M., Veynante, D., Boughanem, H., Trouvé, A.: Direct numerical simulation analysis of flame surface density concept for large eddy simulation of turbulent premixed combustion. Proc. Combust. Inst. 27(1), 917–925 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0082-0784(98)80489-X

Borghi, R., Dutoya, D.: On the scales of the fluctuations in turbulent combustion. Symp. Combust. 17(1), 235–244 (1979). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0082-0784(79)80025-9

Bray, K.N.C.: The interaction between turbulence and combustion. Seventeenth Symp. Symp. Combust. 17(1), 223–233 (1979). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0082-0784(79)80024-7

Bruneaux, G., Akselvoll, K., Poinsot, T.J., Ferziger, J.H.: Flame–wall interaction simulation in a turbulent channel flow. Combust. Flame 107(1–2), 27–36 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-2180(95)00263-4

Bruneaux, G., Poinsot, T.J., Ferziger, J.H.: Premixed flame–wall interaction in a turbulent channel flow: budget for the flame surface density evolution equation and modelling. J. Fluid Mech. 349(–1), S0022112097006769 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112097006769

Candel, S.M., Poinsot, T.J.: Flame stretch and the balance equation for the flame area. Combust. Sci. Technol. 70(1–3), 1–15 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1080/00102209008951608