Abstract

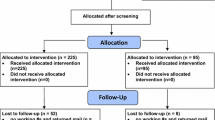

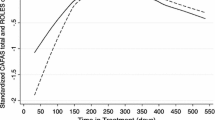

The current investigation conducted descriptive analyses on key variables in community-based residential (CBR) settings and investigated the extent to which disruptive youth between the ages of 13 and 17 years improved based on therapists’ reported alignment with using practices derived from the evidence-base (PDEBs). Results from both the descriptive analyses and multilevel modeling suggested that therapists are using practices that both do and do not align with the evidence-base for disruptive youth. In addition, both PDEBs and practices with minimal evidence-support predicted or marginally predicted final average progress rating for these youth. Findings are discussed as they relate to the importance of continued exploration of treatment outcomes for CBR youth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Within the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division, only level III of the three levels of community-based residential (CBR) settings was included in the study because youth from the Community-Based Residential-I and -II settings have treatment needs that are very specialized (e.g., sexual deviance), as compared to the broad difficulties faced by CBR-III youth. Henceforth, the use of CBR will represent the youth from CBR-III programs only.

When multiple therapists were tied to one youth’s MTPS forms, the therapist that was most frequently linked to the MTPS forms was chosen for analyses. When multiple therapists were tied to one youth’s MTPS forms and the therapists had the same number of MTPS forms completed, the initial therapist was chosen because previous research suggests that a youth typically improves at higher rates earlier as compared to later in treatment (Orimoto et al. 2012b).

As is evident from the PDEBs bolded in Table 4, a few practice elements target parents and teachers (i.e., parent and teacher monitor and praise). These PDEBs were kept in the list of PDEBs used to create the PDEB-score because families are typically incorporated into therapy sessions toward the end of a youth’s stay to help with their transition back home. In addition, youth in residential settings still have teachers who are part of their treatment team within their agency. Hence, both parents and teachers play active roles in the team, but to a different extent as they would in other settings.

This model was originally going to include four-levels, with the fourth level being CBR-III agency. However, due to the small number of agencies in this sample (n = 5), it was removed as a level and was instead included as a variable at the client level (i.e., level-two).

To define the intercept as ending status, the time variable was coded such that the last month of treatment was 0, and the first month of treatment was − 1. The months of treatment between − 1 and 0 varied depending on the length of youth’s treatment episode. For example, a client with 4 months was coded − 1, -0.66, -0.33, and 0, while a client with 9 months was coded − 1, − 0.825, − 0.75, − 0.675, − 0.5, − 0.325, − 0.25, − 0.175, and 0.

Variables were either centered around the grand mean or their minimum values in order to facilitate interpretation of the intercept. These decisions to center variables did not change their slopes; hence, the choices were made based on how best to aide in the interpretation of the intercept.

It should be noted that the sample was initially restricted to those youth who had two or more months of CBR treatment to ensure that there was enough data points to see a change in progress rating over time. However, after the remainder of the inclusionary criteria were applied (see “Participants” section), the final sample inadvertently had a minimum of 3 months of treatment.

References

Aarons, G. A., Hurlburt, M., & Horwitz, S. M. (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Related Services, 38, 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7.

Baumann, B. L., Kolko, D. J., Collins, K., & Herschell, A. D. (2006). Understanding practitioners’ characteristics and perspectives prior to the dissemination of an evidence-based intervention. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30(7), 771–787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.01.002.

Bickman, L. (2000). The most dangerous and difficult question in mental health services research. Mental Health Services Research, 2(2), 71–72. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010100119789.

Borntrager, C. F., Chorpita, B. F., Orimoto, T., Love, A., & Mueller, C. W. (2013). Validity of clinician’s self-reported practice elements on the monthly treatment and progress summary. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, 42(3), 367–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-013-9363-x.

Brookman-Frazee, L., Haine, R. A., Baker-Ericzén, M., Zoffness, R., & Garland, A. F. (2010). Factors associated with use of evidence-based practice strategies in usual care youth psychotherapy. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 37(3), 254–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-009-0244-9.

Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division. (2005). Service provider monthly treatment and progress summary. Honolulu: Hawaii Department of Health, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division.

Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division, Hawaii Department of Health Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division. (2012). Child and Adolescent Mental Health Performance Standards Interagency Performance Standards and Practice. Retrieved from http://health.hawaii.gov/camhd/.

Chorpita, B. F., & Daleiden, E. (2009). Evidence-based services committee—Biennial report—Effective psychological interventions for youth with behavioral and emotional needs. Honolulu: Hawaii Department of Health Child & Adolescent Mental Health Division.

Chorpita, B. F., Daleiden, E. L., & Weisz, J. R. (2005). Identifying and selecting the common elements of evidence-based interventions: A distillation and matching model. Mental Health Services Research, 7, 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11020-005-1962-6.

Daleiden, E. L., Lee, J., & Tolman, R. (2004). Annual report. Honolulu, HI: Hawaii Department of Health, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division.

Daleiden, E. L., Pang, D., Roberts, D., Slavin, L. A., & Pestle, S. L. (2010). Intensive home based services within a comprehensive system of care for youth. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 318–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9300-z.

Denenny, D., & Mueller, C. (2012). Do empirically supported packages or their practices predict superior therapy outcomes for youth with conduct disorders? Paper presented at the forty-sixth annual convention of the association of behavioral and cognitive therapies, National Harbor, MD.

Garland, A. F., Brookman-Frazee, L., Hurlburt, M. S., Accurso, E. C., Zoffness, R. J., Haine-Schlagel, R., & Ganger, W. (2010). Mental health care for children with disruptive behavior problems: A view inside therapists’ offices. Psychiatric Services, 61(8), 788–795. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.61.8.788.

Garland, A. F., Hawley, K. M., Brookman-Frazee, L., & Hurlburt, M. S. (2008). Identifying common elements of evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children’s disruptive behavior problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(5), 505–514. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816765c2.

Garland, A. F., Hurlburt, M. S., & Hawley, K. M. (2006). Examining psychotherapy processes in a services research context. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13, 30–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00004.x.

Heck, R. H., Thomas, S. L., & Tabata, L. N. (2013). Multilevel and longitudinal modeling with IBM SPSS: Quantitative methodology series. (second edition). New York: Routledge.

Higa-McMillan, C., Powell, C. K. K., Daleiden, E. L., & Mueller, C. W. (2011). Pursuing an evidence -based culture through contextualized feedback: Aligning youth outcomes and practices. Professional Psychology: Research & Practice, 42(2), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022139.

Higa-McMillan, C. K., Nakamura, B. J., Morris, A., Jackson, D. S., & Slavin, L. (2014). Predictors of use of evidence-based practices for children and adolescents in usual care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(4), 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-014-0578-9.

Hoagwood, K., & Kolko, D. J. (2009). Introduction to the special section on practice contexts: A glimpse into the nether world of public mental health services for children and families. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services, 36(1), 35–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-008-0201-z.

Hodges, K. (1990, 1994 revision). Child and adolescent functional assessment scale. Ypsilanti: Eastern Michigan University, Department of Psychology.

Hodges, K., & Gust, J. (1995). Measures of impairment for children and adolescents. Journal of Mental Health Administration, 22(4), 403–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02518634.

Hodges, K., & Wong, M. M. (1996). Psychometric characteristics of a multidimensional measure to assess impairment: The Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 5(4), 445–467. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02233865.

Izmirian, S. C., Nakamura, B. J., Hill, K. A., Higa-McMillan, C. K., & Slavin, L. (2016). Therapists’ knowledge of practice elements derived from the evidence-base: Misconceptions, accuracies, and large-scale improvement guidance. Professional Psychology: Research & Practice. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000081. Advanced online publication.

Kazdin, A. E. (1995). Child, parent and family dysfunction as predictors of outcome in cognitive-behavioral treatment of antisocial children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00053-M.

Keir, S. S., Jackson, D. S., Mueller, C. W., & Wilkie, D. (2014). Child and adolescent mental health division: Fiscal year 2013 annual factbook. Retrieved from Hawaii Department of Health Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division website: http://health.hawaii.gov/camhd/resource-library/research-and-evaluation/.

Love, A., Orimoto, T., Powell, A., & Mueller, C. (2011, November). Examining the relationship between therapist-identified treatment targets and youth diagnoses using exploratory factor analysis. Paper presented at the Forty-Fifth Annual Convention of the Association of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, Toronto, Ontario.

Love, A. R. (2014). A Multilevel longitudinal analysis of the relationship between therapist use of practices derived from the evidence base and outcomes for youth with mood disturbances in community-based mental health (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Lyons, J. S., & McCulloch, J. R. (2006). Monitoring and managing outcomes in residential treatment: Practice-based evidence in search of evidence-based practice. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(2), 247–251. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000190468.78200.4e.

Mueller, C., Daleiden, E., Chorpita, B., Tolman, R., & Higa-McMillan, C. (2009, August). Evidence-based service practice elements and youth outcomes in a state-wide system. In A. Marder (Chair), A demonstration of mapping and traversing the science-practice gap. Symposium conducted at the American Psychological Association, Toronto, Canada.

Mueller, C. W., Tolman, R., Higa-McMillan, C. K., & Daleiden, E. L. (2010). Longitudinal predictors of youth functional improvement in a public mental health system. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 37(3), 350–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-009-9172-4.

Nakamura, B. J., Daleiden, E. L., & Mueller, C. W. (2007). Validity of treatment target progress ratings as indicators of youth improvement. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16(5), 729–741. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-006-9119-9.

Nakamura, B. J., Mueller, C. W., Higa-McMillan, C., Okamura, K. H., Chang, J. P., Slaving, L., & Shimabukuro, S. (2014). Engineering youth services system infrastructure: Hawaii’s continued efforts at large-scale implementation through knowledge management strategies. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 43(2), 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.812039.

Norcross, J. C., & Karpiak, C. P. (2012). Clinical psychologists in the 2010s: 50 years of the APA division of clinical psychology. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 19(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2012.01269.x.

Orimoto, T. E., Higa-McMillan, C. K., Mueller, C. W., & Daleiden, E. L. (2012a). Assessment of therapy practices in community treatment for children and adolescents. Psychiatric Services, 63(4), 343–350. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100129.

Orimoto, T. E., Jackson, D., Keir, S., Ku, J., & Mueller, C. W. (2012b). Is less more? Patterns in client change across levels of care in youth public health services. Paper presented at the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, National Harbor, MD.

Orimoto, T. E., Mueller, C. W., Hayashi, K., & Nakamura, B. J. (2014). Community-based treatment for youth with co- and multimorbid disruptive behavior disorders. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(2), 262–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-012-0464-2.

Orimoto, T. E., Mueller, C. W., & Nakamura, B. J. (2013). Fusing science and practice: Predicting progress ratings for disruptive behavior targets with practices derived from the evidence-based in community treatments. In R. Beidas & B. McLeod (Chair) and M. Southam-Gerow (Discussant), Translating evidence-based assessment and treatments for youth for deployments in community settings. Symposium presented at the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, Nashville, TN.

Pardini, D., & Fite, P. (2010). Symptoms of conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and callous-unemotional traits as unique predictors of psychosocial maladjustment in boys: Advancing an evidence base for DSM-V. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49, 1134–1144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.07.010.

PracticeWise, L. L. C. (2014). PracticeWise evidence-base services database. Retrieved from https://www.practicewise.com.

Soni, A. (2009). The five most costly children’s conditions, 2006: Estimates for the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized children, ages 0–17. Statistical Brief #242. Agency for healthcare research and quality, Rockville, MD, April 2009. http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st242/stat242.pdf.

Southam-Gerow, M. A., Daleiden, E. L., Chorpita, B. F., Bae, C., Mitchell, C., Faye, M., & Alba, M. (2013). MAPping Los Angeles Country: Taking an evidenced-informed model of mental health care to scale. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43(2), 190–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.833098.

Weersing, V. R., & Weisz, J. R. (2002). Community clinic treatment of depressed youth: Benchmarking usual care against CBT clinical trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(2), 299–310. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.70.2.299.

Weisz, J. R., Chorpita, B. F., Palinkas, L. A., Schoenwald, S. K., Miranda, J., Bearman, S. K., & … The Research Network on Youth Mental Health (2012). Testing standard and modular designs for psychotherapy treating depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in youth - A randomized effectiveness trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(3), 274–282. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.147.

Weisz, J. R., & Jensen, A. L. (2001). Child and adolescent psychotherapy in research and practice contexts: Review of the evidence and suggestions for improving the field. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 10(1), 112–118.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Izmirian and Dr. Chang declare that they have no conflict of interests. Dr. Nakamura has received funding from the State of Hawaii Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division, and does a small amount of consulting for PracticeWise, LLC.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Research Involved in Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Izmirian, S.C., Chang, J.P. & Nakamura, B.J. Predicting Youth Improvement in Community-Based Residential Settings with Practices Derived from the Evidence-Base. Adm Policy Ment Health 46, 458–473 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-00925-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-00925-2