Abstract

The Gram-stain-negative, oxidase negative, catalase positive strain KPC-SM-21T, isolated from a digestate of a storage tank of a mesophilic German biogas plant, was investigated by a polyphasic taxonomic approach. Phylogenetic identification based on the nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene revealed highest gene sequence similarity to Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606T (97.0%). Phylogenetic trees calculated based on partial rpoB and gyrB gene sequences showed a distinct clustering of strain KPC-SM-21T with Acinetobacter gerneri DSM 14967T = CIP 107464T and not with A. baumannii, which was also supported in the five housekeeping genes multilocus sequence analysis based phylogeny. Average nucleotide identity values between whole genome sequences of strain KPC-SM-21T and next related type strains supported the novel species status. The DNA G + C content of strain KPC-SM-21T was 37.7 mol%. Whole-cell MALDI-TOF MS analysis supported the distinctness of the strain to type strains of next related Acinetobacter species. Predominant fatty acids were C18:1 ω9c (44.2%), C16:0 (21.7%) and a summed feature comprising C16:1 ω7c and/or iso-C15:0 2-OH (15.3%). Based on the obtained genotypic, phenotypic and chemotaxonomic data we concluded that strain KPC-SM-21T represents a novel species of the genus Acinetobacter, for which the name Acinetobacter stercoris sp. nov. is proposed. The type strain is KPC-SM-21T (= DSM 102168T = LMG 29413T).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The genus Acinetobacter is highly diverse (Touchon et al. 2014) and was first described by Brisou and Prévot (1954). Members of this genus are Gram-negative coccobacilli, non-motile, non-spore forming, aerobic, oxidase negative and catalase positive bacteria. This genus comprises non-fermentative bacteria, which can survive under different environmental conditions for extended periods through a wide temperature range. Over the past decades, some species of this genus have emerged as significant nosocomial and opportunistic pathogens causing outbreaks of colonization and infection, especially in critically ill patients with impaired immunity (Dijkshoorn et al. 2007; Peleg et al. 2008; Towner 2006; Visca et al. 2011). Accumulation of antibiotic resistances in Acinetobacter spp. is an increasing problem for the global public health (Visca et al. 2011). Acinetobacter baumannii represents one of the “ESKAPE pathogens” which can cause life-threatening nosocomial infections and can harbor several drug resistance mechanisms (Rice 2008; Bush and Jacoby 2010). At the time of writing, the genus Acinetobacter comprised 59 distinct species with validly published names (https://lpsn.dsmz.de/genus/acinetobacter; Parte 2018), as well as several species and genomic species without validly published names. Most of the species of Acinetobacter were obtained exclusively from human clinical specimens (Nemec et al. 2001, 2003, 2010, 2011, 2015, 2016, 2017). However, others were isolated from environmental sources, such as activated sludge (Carr et al. 2003), wetlands (Anandham et al. 2010), forest soil (Kim et al. 2008), seawater (Di Cello et al. 1997; Vaneechoutte et al. 2009), dumpsites (Malhotra et al. 2012), wastewater (Vaz-Moreira et al. 2011), freshwater (Li et al. 2014; Radolfova-Krizova et al. 2016), cotton and soil (Nishimura et al. 1988; Choi et al. 2013). Furthermore, Rafei et al. (2015) reported as many as 30 putative novel species of Acinetobacter in a non-human epidemiological study in Lebanon, which suggested that this genus is geographically more distributed than originally supposed.

In an attempt to isolate carbapenem-resistant bacteria released from biogas plants (anaerobic processing condition) digestates into the environment, strain KPC-SM-21T was isolated in October 2013 from the digestate collected from one of the studied German biogas plants (Schauss et al. 2015). Here, detailed phenotypic, genotypic and chemotaxonomic studies of strain KPC-SM-21T were performed and the taxonomic status was concluded. Based on morphological, physiological, biochemical and genotypic characteristics obtained on the notion of a polyphasic approach, we propose a novel species of the genus Acinetobacter with strain KPC-SM-21T as type strain. Besides, genes encoding antibiotic resistance, virulence and bacteriophages were identified, and survival of this strain in anaerobic condition was also investigated.

Materials and methods

Isolation and culture condition

The studied strain was isolated in 2013 from a digestate sample obtained from the final storage tank of a biogas plant (BGP-1) located in the North of Hesse, Germany. The input material of the biogas plant was composed of 54% slurry (20:1 cattle to pig) and 46% manure (6:1 cattle to chicken) and corn and forage rye as co-substrates (Schauss et al. 2015). The biogas plant contained a continuous stirred tank reactor (CSTRs) typical for German on farm small scale systems with a two stage mesophilic digestion process (T = 44 °C). Strain KPC-SM-21T was cultured by a selective pre-enrichment method which was applied to culture carbapenem-resistant bacteria from the collected output material. Briefly, 10 g digestate of the storage tank was incubated directly in 90 mL sterile lysogen broth (LB, Sigma-Aldrich) containing 1 mg L−1 meropenem (MER: C17H25N3O5S3H2O, Sigma-Aldrich). After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C under continuous shaking at 180 rpm, 10 µL of the pre-enrichment culture was streaked on CHROMagar KPC (CHROMagar, France). The agar plate was incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. Among morphologically different colonies grown on the agar plates, one of separately lying cream-colored colony represented strain KPC-SM-21T which was obtained as pure culture after multiple transfer steps of single colony following singular streaking on CHROMagar KPC. After purification, fresh biomass of strain KPC-SM-21T was cultured on LB agar containing 1 mg L−1 meropenem and suspended in sterile Gibco newborn calf serum (NBCS, ThermoFisher Scientific) and stored at − 20 °C and − 80 °C for long-term preservation.

Phylogenetic identification

Bacterial cell lysate and 16S rRNA gene sequencing for molecular analyses was generated and performed as described by Schauss et al. (2015). Universal 16S rRNA gene targeting primers [8F: 5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′ and 1492R: 5′-CGGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′; (Turner et al. 1999)] were used for PCR and primers 27F [5′-GAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′; (Lane 1991)] and E786F [5′-GATTAGATACCCTGGTAG-3′; (Baker et al. 2003)] for Sanger sequencing performed at LGC Genomics (Berlin, Germany). The partial gene sequences were corrected in MEGA7 (Kumar et al. 2016) based on electropherograms and concatenated to a nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene sequence. Next related type strains were determined using the EzBioCloud 16S rRNA gene identification system (Yoon et al. 2017). The phylogenetic relationship of KPC-SM-21T to the type strains of the genus Acinetobacter, including several genomic species and multiple species without validly published names, was studied based on nearly complete 16S rRNA gene sequences. 16S rRNA genes sequences of all representatives of this genus were retrieved from the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/) and aligned with ClustalW (Thompson et al. 1994) provided in MEGA7. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the maximum-likelihood method (ML; Felsenstein 1981) based on the Kimura 2-parameter model (Kimura 1980). The consistency of the phylogenetic tree was investigated by 100 resamplings (bootstrap analysis; Felsenstein 1985). Moreover, phylogenetic analyses with higher resolution were performed based on protein coding sequences including the RNA polymerase β-subunit (rpoB) and DNA gyrase subunit B (gyrB) genes as described previously (Nemec et al. 2009; Krizova et al. 2014). Alignments of the nucleotide sequences of each gene were performed based on the respective correct open reading frame (ORF). Pairwise nucleotide sequence similarities were determined with the p-distance method implemented in MEGA7. Phylogenetic analyses were performed using the ML method based on the General Time Reversible (GTR; Nei and Kumar 2000) model for nucleotide and the Jones–Thornton-̄Taylor matrix-based (JTT; Jones et al. 1992) model for amino acid sequence based analysis. Multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) was performed based on genes used in the multilocus sequence typing (MLST) scheme (Pasteur; https://pubmlst.org/abaumannii/) for A. baumannii (Diancourt et al. 2010). Partial sequences of six housekeeping genes were used for MLSA analysis. The genes code for CTP synthase (PyrG), 60-KDa chaperonin (Cpn60), citrate synthase (GltA), homologous recombination factor (RecA), 50S ribosomal protein L2 (RplB) and the beta-subunit of the RNA polymerase (RpoB), respectively. The rpoB gene fragment used in the MLSA approach [spanning nucleotide positions 1681–2136 of the rpoB gene of A. baumannii CIP 70.34T (DQ207471)] was different from that applied in the rpoB gene based phylogeny. Full-length sequences of these housekeeping genes for type strains of Acinetobacter species were obtained from the NCBI database. Sequences were aligned based on the correct ORF and concatenated in the following order: pyrG (297 nt), cpn60 (405 nt), gltA (483 nt), recA (361 nt), rplB (330 nt) and rpoB (456 nt) based on their respective sizes. The gene encoding for elongation factor G (FusA), mentioned in the MLST scheme, was not used in MLSA, since the amplification result of the fusA gene was unsatisfactory. The evolutionary history was inferred using the ML method based on the GTR model (Nei and Kumar 2000).

Genome sequencing, core genome based phylogeny and genome‐wide analysis

A draft genome sequence of strain KPC-SM-21T was generated by Illumina short read sequencing (read out 2 × 300 bp, MiSeq benchtop sequencer) followed by sequence reconstruction using the A5-miseq assembly pipeline. Genome sequence based analyses were performed in EDGAR 2.3 (Blom et al. 2016). The genome sequence of strain KPC-SM-21T and genome sequences of Acinetobacter species (validly published) type strains and strains representing distinct genomic species with provisional designation or Acinetobacter species without names standing in nomenclature were obtained from the NCBI database and integrated into an EDGAR project. The BLAST search of the 16S rRNA gene sequence of strain KPC-SM-21T showed 99.7% similarity to the 16S rRNA gene of Acinetobacter sp. Marseille-Q1620 (LR782267.1). Therefore, the genome of Acinetobacter sp. Marseille-Q1620 (NZ_LR782267) was also included to determine the taxonomic position of strain KPC-SM-21T.

The taxonomic status at the whole genome level was assessed by calculating average nucleotide identity (ANI) values. An ANI matrix was calculated in EDGAR based on the BLASTN comparison of the genome sequences as described by Goris et al. (2007). A core genome based phylogenetic analysis was calculated in EDGAR following a stepwise alignments of each core gene set using MUSCLE (implemented in EDGAR 2.3) the final alignments were concatenated to one huge alignment, which included shared genes of the genome of strain KPC-SM-21T, the Acinetobacter reference genomes and the genome of Moraxella lacunata NBRC 102154T (NZ_BCUK00000000) which was used as outgroup. Thereafter, a core genome based phylogenetic analysis was computed using the FastTree software (http://www.microbesonline.org/fasttree/) to generate approximately-maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees (Price et al. 2009, 2010) implemented in EDGAR 2.3. The genome-based circular plot was generated with BioCircos (Cui et al. 2016) implemented in EDGAR 2.3. Furthermore, EDGAR 2.3 and VFDB (virulence factor database; http://www.mgc.ac.cn/VFs/) were used to identify resistance and virulence associated genes. Genomic islands (GIs) were searched with IslandViewer4 (Bertelli et al. 2017; Bertelli and Brinkman 2018). Potential phage-related genes of strain KPC-SM-21T were identified using PHASTER (https://phaster.ca/; Zhou et al. 2011; Arndt et al. 2016).

Matrix‐assisted laser desorption ionization time‐of‐flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS)

For MALDI-TOF MS the strain was grown on Columbia agar with 5% sheep blood (SBA; Oxoid) for 24 h. The experiment was performed as described by Eisenberg et al. (2017). Biomass was transferred to steel targets using the direct transfer protocol according to the manufacturer’s instruction (MALDI Biotyper; Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). Analysis was performed on a MALDI-TOF MS Biotyper version 3.3.1.0; commercial database (DB 8468; BrukerDaltonics). The MALDI Biotyper real-time classification (RTC) software calculated obtained log score based on similarities between the observed results and stored database sets. Log scores of > 2.3 and > 2.0 were considered as species and genus level identifications, respectively. The identification was repeated three times to verify the original findings.

Fatty acid analysis

Biomass for fatty acid analysis was harvested after growth on trypticase soy agar (TS agar; Becton Dickinson GmbH) at 30 °C for 48 h (exponentially growing cells). The analysis was performed as described by Kämpfer and Kroppenstedt (1996) using the Sherlock version 2.11, TSBA40 Rev. 4.1 for identification.

Phenotypic characterization

Cell morphology and motility was observed under a Zeiss light microscope at a magnification of × 1000, using cells grown for three days at 25 °C on TS agar. Gram-staining was performed by the modified Hucker method according to Gerhardt et al. (1994). Cytochrome-c oxidase activity was tested using Bactident oxidase test strips (Merck) and catalase enzyme activity by testing formation of gas bubbles after dropping 3% (v/v) hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) onto overnight grown biomass on TS agar. The test of growth on different agar media and temperature-dependent growth was performed by suspending fresh biomass in 0.9% (w/v) sodium chloride (NaCl); turbidity standardized by 0.5 McFarland. The cell suspension was serially diluted up to 10−5 and 5 µL of each dilution were spotted on following media: TS agar, R2A agar (R2A; Oxoid), nutrient agar (NA; Becton Dickinson), malt agar (Merck), glycine arginine agar (Gly/Arg; Oxoid), CASO agar (Carl Roth), K7 [0.1% (w/v) of yeast extract, peptone, and glucose, agar (15 g L−1), pH 6.8], M65 medium (according to DSMZ), DEV agar (DEV; Merck), Luria Bertani (LB; Sigma-Aldrich), MacConkey agar (Oxoid), PYE [0.3% (w/v) yeast extract and 0.3% (w/v) casein peptone, agar (15 g L−1), pH 7.2)], nutrient broth (NU; Oxoid), marine agar (MA; Becton Dickinson) and SBA, respectively. Thereafter, all plates were incubated at 28 °C and growth was analysed after 7 days. For temperature-dependent growth the serially dilutions were spotted on TS agar plates which were incubated at 4, 10, 15, 20, 25, 28, 30, 37, 45, 50, and 55 °C, respectively, as described by Pulami et al. (2020). The growth was monitored after 24 h, 48 h, 3 and 7 days of incubation. Hemolysis test was performed as previously described by Nemec et al. (2016). The physiological characterization was performed as described by Kämpfer et al. (1991). Furthermore, strain KPC-SM-21T was tested with the API 20 NE kit (BioMérieux) following the instructions of the manufacturer.

Anaerobic growth test

The survival of strain KPC-SM-21T and A. baumannii ATCC 19606T under anaerobic conditions was investigated by taking strains pre-grown (overnight aerobically at 25 °C) on NA plates, and exposing them to anaerobic conditions using the Anaerocult A system (Merck) at the same temperature for 7 days. Thereafter, a loop of biomass was re-inoculated onto fresh NA, and growth was checked after overnight aerobic incubation at 37 °C. The ability of the strain to grow under anaerobic conditions was checked by direct exposure of streaked plates to anaerobic conditions using the Anaerocult A system at 25 °C for 7 days.

Results and discussion

Molecular and genome characteristics

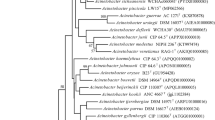

The 16S rRNA gene sequence of strain KPC-SM-21T obtained by Sanger sequencing was 1439 nucleotides in length, spanning gene termini 28 to 1468 [numbering according to the Escherichia coli rrnB (Brosius et al. 1978)], and initial phylogenetic assignment obtained by BLAST against the EzBioCloud database showed 97.0% similarity to A. baumannii ATCC 19606T. Sequence similarities to all type strains of Acinetobacter species were ≤ 97%. This indicated that strain KPC-SM-21T represented a novel species, because all similarity values were below that of 98.65%, which was suggested by Kim et al. (2014) as a pre-requisite threshold to delineate a prokaryotic species. The ML tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences was based on 1223 nucleotide positions. It showed the placement of strain KPC-SM-21T in a separate branch within the genus Acinetobacter without a distinct clustering to any of the other investigated strains including all type strains of the genus (Fig. 1). The rpoB based phylogenetic analyses included gene fragments spanning gene positions 2917–3267 (zone1) and 3322–3723 (zone2), respectively. Gene termini were given according to the gene sequence obtained from A. baumannii CIP 70.34T (DQ207471, La Scola et al. 2006). The nucleotide sequence of the concatenated variable zones of the rpoB gene of strain KPC-SM-21T showed highest sequence similarity to A. gerneri DSM 14967T (91.1%), followed by A. guillouiae CIP 63.46T (86.9%) and A. baylyi DSM 14961T (86.6%); the rpoB sequence similarity to A. baumannii ATCC 19606T was lower (82.6%). The obtained rpoB nucleotide sequence similarity values were below 95% to tested next related type strains of the genus Acinetobacter. La Scola et al. (2006) and Narciso-da-Rocha et al. (2013) have suggested that rpoB gene sequence similarities below 95% represent distinct Acinetobacter species. The ML tree based on rpoB nucleotide (Fig. 2) and amino acid sequences (Fig. S1) showed that strain KPC-SM-21T formed a distinct cluster with A. gerneri DSM 14967T which was supported by high bootstrap values (> 70%). GyrB based phylogenetic analysis was performed with a gene region encompassing nucleotide positions 457–1209 (numbering according to A. baumannii ATCC 19606T (Genome accession number: APRG00000000, Locus tag: 911_RS22805). The gyrB gene sequence based analysis also showed highest nucleotide sequence similarity with A. gerneri DSM 14967T (85.2%). Sequence similarities with all other tested Acinetobacter sp. type strains were below 83.5%. The gyrB nucleotide sequence based phylogenetic tree also showed a distinct cluster of KPC-SM-21T and A. gerneri DSM 14967T. However, this cluster was not supported with a high bootstrap value (Fig. S2). Similarly, the phylogeny based on amino acid sequences of rpoB (Fig. S1) and gyrB (Fig. S3) also showed the placement of strain KPC-SM-21T in a separate branch within the genus Acinetobacter. The ML tree based on MLSA data placed strain KPC-SM-21T in a separate branch beside other Acinetobacter sp. type strains (Fig. S4). Interspecies similarities of strain KPC-SM-21T to other type strains was in the range of 82.7–89.4% (concatenated nucleotide sequences).

Phylogenetic placement of strain KPC-SM-21T within the genus Acinetobacter based on nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene sequences. The maximum-likelihood tree was generated in MEGA7 and is based on nucleotide positions 28–1468 (according to E. coli numbering; Brosius et al. 1978). The respective gene sequence of the type strain of Moraxella lacunata was used as outgroup. Numbers at nodes represent bootstrap values (> 70%) based on 100 replications. Filled circles indicate nodes that were conserved in a tree generated with the neighbour-joining (NJ) method. GenBank accession numbers are given in parentheses. Bar, 0.01 substitutions per nucleotide position

Phylogenetic placement of strain KPC-SM-21T within the genus Acinetobacter based on nucleotide sequences of concatenated variable zones of the rpoB gene. The tree was calculated with the ML method based on 753 nucleotide positions in the final dataset. Numbers at nodes represent the percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in bootstrap tests (100 replications). Only bootstrap values of 70% and above were shown. Filled circles indicate nodes that were also present in a tree generated with the NJ method. Moraxella lacunata NBRC 102154T was used as outgroup. Bar, 0.01 substitutions per sequence position

Prior to genome sequence-based analyses, the 16S rRNA gene sequence present in the genome sequence on contig OOGT01000238 (locus_tag: KPC_R004) was aligned with the Sanger sequenced 16S rRNA gene; both were identical. The draft genome sequence of strain KPC-SM-21T (accession number OOGT01000000, Bioproject: PRJEB25537) had a total nucleotide length of 4.16 Mbp. The core genome-based phylogenetic tree (Fig. 3) showed distinct cluster of strain KPC-SM-21T including Acinetobacter sp. Marseille-Q1620 with A. gerneri DSM 14967T, respectively. The relationship between strain KPC-SM-21T, Acinetobacter sp. Marseille-Q1620, A. gerneri DSM 14967T and A. baumannii ATCC 19606T at whole genome level was assessed by calculating average nucleotide identity (ANI) values in EDGAR 2.3. The ANI values were 98.3% (KPC-SM-21T vs. Acinetobacter sp. Marseille-Q1620), 77.7% (KPC-SM-21T vs. A. gerneri DSM 14967T) and 73.6% (KPC-SM-21T vs. A. baumannii ATCC 19606T), respectively (Fig. S5). The core genome-based phylogeny and ANI values proved that strain KPC-SM-21T and Acinetobacter sp. Marseille-Q1620 belonged to the same cluster of species and are genomically closely related. The ANI values against A. gerneri DSM 14967T and A. baumannii ATCC 19606T were below the threshold of ~ 95–96% proposed to discriminate between prokaryotic species (Richter and Rosselló-Móra 2009). The genomic DNA G + C content of strain KPC-SM-21T was 37.7 mol%, which was similar to that of the two closely related type strains, 39.2 mol% for A. baumannii ATCC 19606T and 37.9 mol% for A. gerneri DSM 14967T, respectively.

Phylogenetic tree based on 65 genomes, built out of a core of 668 genes per genome; 43,420 in total using EDGAR 2.3 (Blom et al. 2016), applying the FastTree software (http://www.microbesonline.org/fasttree/) to generate an approximately-ML phylogenetic tree (Price et al. 2009, 2010). The values at the branches show local support values in percentage computed by FastTree using the Shimodaira–Hasegawa test. The core has 720,855 amino acid residues per genome and 46,855,575 in total. The genome of Moraxella lacunata NBRC 102154T (NZ_BCUK00000000) was used to root the tree. Bar, 0.05 substitutions per amino acid sequence residue

Therefore, on the basis of 16S rRNA gene, rpoB comparative analysis, gyrB phylogeny, and MLSA, strain KPC-SM-21T was distinct from the type strains of Acinetobacter species with validly published names, genomic species with provisional designation or Acinetobacter species without names standing in nomenclature. Notably, ANI values and core genome-based phylogeny proved the high similarity between strain KPC-SM-21T and Acinetobacter sp. Marseille-Q1620 below the threshold of prokaryotic species. The strains clustered with the type strain of A. gerneri which is represented by two genome sequences (A. gerneri DSM 14967T and A. gerneri CIP 63.46T).

Assignment by MALDI-TOF and fatty acid analysis

MALDI-TOF data confirmed the genotypic identification of strain KPC-SM-21T as novel Acinetobacter species. The dendrogram based on MALDI-TOF data showed a distinct clustering of strain KPC-SM-21T (Fig. S6) among type strains of next related Acinetobacter species. The average log score was 1.56, which was a non-reliable score that can be explained by absence of a close relative of KPC-SM-21T in the database used. Therefore, and in a comparison with other species from the same genus, strain KPC-SM-21T represented a distinct species of the genus Acinetobacter on the basis of MALDI-TOF data.

The predominant fatty acids of KPC-SM-21T were C18:1 w9c (44.17%), C16:0 (21.67%) and summed feature 3* (15.34%) (containing C16:1 ω7c and/or iso-C15:0 2-OH that was not determined by Sherlock version). The fatty acid pattern is typical for the genus Acinetobacter (Kämpfer et al. 1993; Kim et al. 2008; Vaz-Moreira et al. 2011). The presence of minor amounts of C18:3 ω6c (2.2%) differentiated strain KPC-SM-21T from type strains of A. baumannii, A. gerneri and A. guillouiae, respectively. The details of the fatty acid profile is given in Table 1.

Phenotypic characteristics

Cells of strain KPC-SM-21T were Gram-negative, oxidase negative, catalase positive and non-motile coccobacilli as typical for members of the genus Acinetobacter. The optimum growth temperature was 25–37 °C; growth occurred at 45 °C and 10 °C, but not at 50 °C and 4 °C. Growth at 45 °C differentiated strain KPC-SM-21T from type strains of A. gerneri (Carr et al. 2003) and A. guillouiae (Nemec et al. 2010). Good growth occurred at 28 °C after 24 h on TS agar, R2A, NA, malt, Gly/Arg, CASO, K7, M65, DEV, LB, PYE, NU, and SBA. Very weak growth on MA, and no growth on MacConkey agar was observed. A zone of hemolysis was not formed on SBA. The outcome of microscopy, growth at different media and range of temperature are provided in supporting information (Fig. S7, S8 and S9). Strain KPC-SM-21T grew on a broad range of carbon sources, and showed acidification of some sugars, as α-d-glucose, α-d-lactose, l-arabinose, d-xylose, d-cellobiose, α-d-melibiose and d-mannose. However, acid production from several sugars and sugar-related compounds was not observed. Physiological tests performed with 96 wells test panel (Kämpfer et al. 1991) resulted difference in comparison with the members of the genus Acinetobacter. Briefly, the ability to produce acid from α-d-melibiose, and assimilation of cis-aconitate, l-aspartate, l-histidine and l-tryptophan differentiated strain KPC-SM-21T form A. gerneri 9A01T = DSM 14967T. Formation of acid from d-glucose, d-mannose, α-d-melibiose, α-d-lactose, d-xylose and l-arabinose, and assimilation of cis-aconitate, l-phenylalanine and l-tryptophan differentiated the strain from members of A. guillouiae (genospecies 11). Lack of assimilation of trans-aconitate, l-arginine and l-leucine differentiated the strain from the members of A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii (ACB) complex. The discriminating physiological characteristics are provided in Table 2.

Antibiotic resistance, virulence and phage associated genes

Although strain KPC-SM-21T was isolated from non-clinical environment (output digestate of a biogas plant), it shared virulence related genes, for instance, those involved in immune evasion and cellular invasion, persistence, serum resistance, host cell lysis, inhibition of blood coagulation, in vivo survival and interspecies competition for host colonization previously reported among nosocomial A. baumannii strains (detailed in Table S2). The protein-protein BLAST (Blastp) of the metalloprotease (CpaA, Table S2) of strain KPC-SM-21T shared 59% (99% query coverage) and 55.5% (99% query coverage) amino acid sequence homology with CpaA of Acinetobacter sp. TGL-Y2 (accession: WP_067658284) and A. baumannii (accession: WP_153566028). This gene was absent in A. gerneri DSM 14967T (APPN00000000) which was a close relative of strain KPC-SM-21T, and also in the clinical strains ATCC 19606T and ATCC 17978T of A. baumannii isolated during middle of the last century (Tilley et al. 2014). Strain KPC-SM-21T harboured an intrinsic blaOXA−like Class D beta lactamase (Locus tag: KPC_0052) without transposition of insertion sequence element upstream this gene, and the strain also lacked potent acquired antibiotic resistance genes. As indicated by Perichon et al. (2014) the class D beta lactamase genes appeared to be intrinsic to several species of the genus Acinetobacter. Genomic islands (GIs) searched with IslandViewer4 showed absence of GIs with acquired resistance in the genome of strain KPC-SM-21T. Potential phage-related gene search in PHASTER showed five incomplete and fragmented phages integrated into the genome. Additionally, a phage with putative intact region (34.6 kb) available in contig NZ_OOGT01000008.1 of strain KPC-SM-21T was found (Fig. 4 and Table S3). The intact phage region harboured segments that coded putative phage-like protein, putative head protein, putative tail protein, putative fiber protein and multiple hypothetical proteins, however lacked regions that code proteins responsible for termination, integration and lysis which are required for propagation inside the host bacterium (Casjens 2003; Canchaya et al. 2003; Labrie et al. 2010) (Fig. S10). This intact phage region shared 51.3% of proteins (data from PHASTER) with PHAGE_Acinet_YMC11/11/R3177 (GenBank accession: NC_041866) (Table S3).

Survival in anaerobic conditions

Both strains, KPC-SM-21T and A. baumannii ATCC 19606T, failed to grow under anaerobic conditions. However, both survived in anaerobic conditions on NA plates for a week at 25 °C, and thereafter grew well in aerobic conditions at 37 °C (data not shown). Even though the genus Acinetobacter is generally regarded as obligate aerobe, they can survive in different anaerobic or oxygen-limited environments, including anaerobic digesters (Supaphol et al. 2011; Baek et al. 2014; Jo et al. 2015). Recently Higgins et al. (2018) reported that Acinetobacter spp. survived the activated anaerobic mesophilic sludge digestion in wastewater treatment plants, but were ultimately killed in alkaline lime-treated stabilized sludge. The authors illustrated in lab scale tests that Acinetobacter spp. were not able to grow under anaerobic conditions but survived an incubation period of four weeks under the same conditions. The digestate of the anaerobic biogas process strain KPC-SM-21T was isolated from represented the same type of environment. Retrospective studies have shown that Acinetobacter spp. accumulated efficiently intracellular polyphosphates, and thereby contributing to a minor extent to the phosphate elimination in sewage treatment plants (Fuhs and Chen 1975; Deinema et al. 1980, 1985; Wentzel et al. 1986; Bark et al. 1992; Van Groenestijn et al. 1987) reported that the accumulated polyphosphates in cells act as a phosphorus reserve and might be used as energy source by enzymatic processing of the polyphosphates via combined action of polyphosphate:AMP phosphotransferase and an adenylate kinase. Comparative genome analyses performed in EDGAR revealed the presence of genes that code for these enzymes in the KPC-SM-21T genome (Fig. S11). This process could explain the survival of aerobic organisms in anaerobic biogas plant or anaerobic sludge treatment, because the polyphosphate reservoir in Acinetobacter cells can be vital under anaerobic environment conditions when these strict aerobes have no other source to generate energy (Kortstee et al. 1994).

Conclusions

The reported phenotypic, chemotaxonomic, and genotypic characteristics congruently showed that KPC-SM-21T (genomically highly similar to Acinetobacter sp. Marseille-Q1620 based on ANI value and core genome-based phylogeny) represents a novel species within the genus Acinetobacter, which is distinct from all hitherto described members of Acinetobacter at the species level of resolution. Next related species are A. gerneri (based on MLSA and core genome based phylogeny) and A. baumannii (based on 16S rRNA gene sequence identity). Although the physiological and molecular analyses revealed that A. gerneri CIP 107464T = DSM 14967T = KCTC 12415T was next related to KPC-SM-21T, these two taxonomic entities were unequivocally different and distant from each other at the level of species based on all characteristics studied above. The name Acinetobacter stercoris sp. nov. is proposed, which indicates, that the bacterium was isolated from output manure of a biogas plant. The type strain is KPC-SM-21T (= DSM 102168T = LMG 29413T).

Description of Acinetobacter stercoris sp. nov.

Acinetobacter stercoris (ster´co.ris. L.N. stercus faeces; L. gen. n. stercoris of manure, referring to the source of the isolate).

Cells are Gram-negative, oxidase negative, catalase positive, non-hemolytic, non-motile and coccobacilli. The optimum growth temperature is 25–37 °C; growth occurs at 45 °C and 10 °C, but not at 50 °C and 4 °C. Good growth occurred at 28 °C after 24 h on TS agar, R2A, NA, malt, Gly/Arg, CASO, K7, M65, DEV, LB, PYE, NU, and SBA. Very weak growth on MA, and no growth on MacConkey agar was observed. Tests for nitrate reduction, indole production, fermentation of d-glucose, urease activity, beta-galactosidase activity, esculin and gelatin hydrolysis were negative (result from API 20 NE). No acid production from d-sucrose, d-mannitol, dulcitol, d-salicin, adonitol, i-inositol, d-sorbitol, a-d-raffinose, α-l-rhamnose, d-maltose, d-trehalose, 1-O-Methyl-d-Glucosidpyranosid, i-erythritol, and d-arabitol. Acid was produced from α-d-glucose, α-d-lactose, l-arabinose, d-xylose, d-cellobiose, α-d-melibiose and d-mannose. Strong assimilation of N-acetyl-d-galactosamine, acetate, propionate, adipate, 4-aminobutyrate, fumarate, glutarate, Dl-lactate, l-malate, 2-oxoglutarate, pyruvate, l-alanine, l-aspartate, l-histidine, l-phenylalanine, l-proline, l-tryptophan, and 4-hydroxybenzoate, and weak assimilation of d-trehalose and (DL-3-) phenylacetate was observed, respectively. No assimilation of N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, p-arbutin, d-cellobiose, d-fructose, d-galactose, d-maltose, d-mannose, α-d-melibiose, (α-) l-rhamnose, d-sucrose, adonitol, I-inositol, maltitol, d-mannitol, d-sorbitol, DL-3-hydroxybutyrate, mesaconate, l-ornithine and 3-hydroxybenzoate, N-acetyl-glucosamine, and potassium gluconate, (d-) gluconate, (α-) d-glucose, d-ribose, d-salicin, putrescine, trans-aconitate, l-leucine and l-serine. Weak assimilation of l-arabinose, d-xylose, cis-aconitate, azelate, and suberate. Strong assimilation of citrate, itaconate, β-alanine, capric acid, adipic acid, d-malate (malic acid), citrate, and phenylacetic acid. No hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside, p-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucuronide, p-nitrophenyl-α-d-glucopyranoside, p-nitrophenyl-phenyl-phosphonate, p-nitrophenyl-phosphate-disodium salt and l-proline-p-nitroanilide, p-nitrophenyl-β-d-xylopyranoside, bis-p-nitrophenyl-phosphate and l-glutamate-γ-carboxy-p-nitroanilide. However, hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside and p-nitrophenyl-phosphoryl-choline was positive. Major fatty acids were C18:1 ω9c, C16:0 and summed feature 3* (containing C16:1 ω7c and/or iso-C15:0 2-OH that was not determined by MIDI system).

The type strain KPC-SM-21T (= DSM 102168T = LMG 29413T) was isolated from the digestate of a biogas plant, located in the North of Hesse, Germany. The genomic DNA G + C content is 37.7 mol%. The NCBI/GenBank accession numbers for the whole draft genome sequence and partial 16S rRNA, rpoB, gyrB and housekeeping genes used in MLSA of KPC-SM-21T were OOGT00000000, MT138756 and MT157622-MT157720, respectively. The complete sequences of 16S rRNA, rpoB and gyrB genes were also provided in the whole genome [16S rRNA (GenBank: OOGT01000238.1; Locus tag: KPC_R004), rpoB (GenBank: OOGT01000016, Locus tag: KPC_0582) and gyrB (GenBank: OOGT01000207.1, Locus tag: KPC_3210)].

Abbreviations

- MALDI-TOF:

-

Matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight

- ANI:

-

Average nucleotide identity

- MLSA:

-

Multilocus sequence analysis

References

Anandham R, Weon H-Y, Kim S-J et al (2010) Acinetobacter brisouii sp. nov., isolated from a wetland in Korea. J Microbiol 48:36–39

Arndt D, Grant JR, Marcu A et al (2016) PHASTER: a better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res 44:W16–W21. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw387

Baek G, Kim J, Lee C (2014) Influence of ferric oxyhydroxide addition on biomethanation of waste activated sludge in a continuous reactor. Bioresour Technol 166:596–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2014.05.052

Baker GC, Smith JJ, Cowan DA (2003) Review and re-analysis of domain-specific 16S primers. J Microbiol Methods 55:541–555

Bark K, Sponner A, Kämpfer P et al (1992) Differences in polyphosphate accumulation and phosphate adsorption by Acinetobacter isolates from wastewater producing polyphosphate: AMP phosphotransferase. Water Res 26:1379–1388. https://doi.org/10.1016/0043-1354(92)90131-M

Bertelli C, Brinkman FSL (2018) Improved genomic island predictions with IslandPath-DIMOB. Bioinformatics. 13:2161–2167

Bertelli C, Laird MR, Williams KP et al (2017) IslandViewer 4: expanded prediction of genomic islands for larger-scale datasets. Nucleic Acids Res 45:W30–W35. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx343

Blom J, Kreis J, Spänig S et al (2016) EDGAR 2.0: an enhanced software platform for comparative gene content analyses. Nucleic Acids Res 44:W22–W28. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw255

Brisou J, Prévot AR (1954) Etudes de systématique bactérienne. X. Révision des especes réunies dans le genre Achromobacter. Ann Inn Pasteur (Paris) 86:722–728 (in French)

Brosius J, Palmer ML, Kennedy PJ, Noller HF (1978) Complete nucleotide sequence of a 16S ribosomal RNA gene from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 75:4801–4805. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.75.10.4801

Bush K, Jacoby GA (2010) Updated functional classification of β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:969–976

Canchaya C, Proux C, Fournous G et al (2003) Prophage genomics. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 67:238–276. https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.67.2.238-276.2003

Carr EL, Kämpfer P, Patel BKC et al (2003) Seven novel species of Acinetobacter isolated from activated sludge. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 53:953–963. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.02486-0

Casjens S (2003) Prophages and bacterial genomics: What have we learned so far? Mol Microbiol 49:277–300

Choi JY, Ko G, Jheong W et al (2013) Acinetobacter kookii sp. nov., isolated from soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 63:4402–4406. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.047969-0

Cui Y, Chen X, Luo H et al (2016) BioCircos.js: an interactive Circos JavaScript library for biological data visualization on web applications. Bioinformatics 32:1740–1742. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btw041

Deinema MH, Habets LHA, Scholten J et al (1980) The accumulation of polyphosphate in Acinetobacter spp. FEMS Microbiol Lett 9:275–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.1980.tb05652.x

Deinema MH, Van Loosdrecht M, Scholten A (1985) Some physiological characteristics of Acinetobacter spp. accumulating large amounts of phosphate. Water Sci Technol 17:119–125. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.1985.0226

Di Cello F, Pepi M, Baldi F, Fani R (1997) Molecular characterization of an n-alkane-degrading bacterial community and identification of a new species, Acinetobacter venetianus. Res Microbiol 148:237–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0923-2508(97)85244-8

Diancourt L, Passet V, Nemec A et al (2010) The population structure of Acinetobacter baumannii: expanding multiresistant clones from an ancestral susceptible genetic pool. PLoS ONE 5:e10034. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010034

Dijkshoorn L, Nemec A, Seifert H (2007) An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat Rev Microbiol 5:939–951

Eisenberg T, Riße K, Schauerte N et al (2017) Isolation of a novel “atypical” Brucella strain from a bluespotted ribbontail ray (Taeniura lymma). Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. Int J Gen Mol Microbiol 110:221–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10482-016-0792-4

Felsenstein J (1981) Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: a maximum likelihood approach. J Mol Evol 17:368–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01734359

Felsenstein J (1985) Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783–791. https://doi.org/10.2307/2408678

Fuhs GW, Chen M (1975) Microbiological basis of phosphate removal in the activated sludge process for the treatment of wastewater. Microb Ecol 2:119–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02010434

Gerhardt P, Murray RGE, Wood WA, Krieg NR (1994) Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC

Goris J, Konstantinidis KT, Klappenbach JA et al (2007) DNA-DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 57:81–91. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.64483-0

Higgins PG, Hrenovic J, Seifert H, Dekic S (2018) Characterization of Acinetobacter baumannii from water and sludge line of secondary wastewater treatment plant. Water Res 140:261–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2018.04.057

Jo Y, Kim J, Hwang S, Lee C (2015) Anaerobic treatment of rice winery wastewater in an upflow filter packed with steel slag under different hydraulic loading conditions. Bioresour Technol 193:53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2015.06.046

Jones DT, Taylor WR, Thornton JM (1992) The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Bioinformatics 8:275–282. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/8.3.275

Kämpfer P, Kroppenstedt RM (1996) Numerical analysis of fatty acid patterns of coryneform bacteria and related taxa. Can J Microbiol 42:989–1005. https://doi.org/10.1139/m96-128

Kämpfer P, Tjernberg I, Ursing J (1993) Numerical classification and identification of Acinetobacter genomic species. J Appl Bacteriol 75:259–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.1993.tb02775.x

Kämpfer P, Steiof M, Dott W (1991) Microbiological characterization of a fuel-oil contaminated site including numerical identification of heterotrophic water and soil bacteria. Microb Ecol 21:227–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02539156

Kim D, Baik KS, Kim MS et al (2008) Acinetobacter soli sp. nov., isolated from forest soil. J Microbiol 46:396–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12275-008-0118-y

Kim M, Oh HS, Park SC, Chun J (2014) Towards a taxonomic coherence between average nucleotide identity and 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity for species demarcation of prokaryotes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 64:346–351. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.059774-0

Kimura M (1980) A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol 16:111–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01731581

Kortstee GJJ, Appeldoorn KJ, Bonting CFC et al (1994) Biology of polyphosphate-accumulating bacteria involved in enhanced biological phosphorus removal. FEMS Microbiol Rev 15:137–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00131.x

Krizova L, Maixnerova M, Sedo O, Nemec A (2014) Acinetobacter bohemicus sp. nov. wide spread in natural soil and water ecosystems in the Czech Republic. Syst Appl Microbiol 37:467–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.syapm.2014.07.001

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K (2016) MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw054

La Scola B, Gundi VAKB, Khamis A, Raoult D (2006) Sequencing of the rpoB gene and flanking spacers for molecular identification of Acinetobacter species. J Clin Microbiol 44:827–832. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.44.3.827-832.2006

Labrie SJ, Samson JE, Moineau S (2010) Bacteriophage resistance mechanisms. Nat Rev Microbiol 8:317–327

Lane DJ (1991) 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M (eds) Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. Wiley, New York, pp 115–175

Lee JS, Lee KC, Kim KK et al (2009) Acinetobacter antiviralis sp. nov., from tobacco plant roots. J Microbiol Biotechnol 19:250–256. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.0901.083

Li W, Zhang D, Huang X, Qin W (2014) Acinetobacter harbinensis sp. nov., isolated from river water. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 64:1507–1513. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.055251-0

Malhotra J, Anand S, Jindal S et al (2012) Acinetobacter indicus sp. nov., isolated from a hexachlorocyclohexane dump site. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 62:288–2890. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.037721-0

Narciso-da-Rocha C, Vaz-Moreira I, Svensson-Stadler L et al (2013) Diversity and antibiotic resistance of Acinetobacter spp. in water from the source to the tap. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 97:329–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-012-4190-1

Nei M, Kumar S (2000) Molecular evolution and phylogenetics. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Nemec A, De Baere T, Tjernberg I et al (2001) Acinetobacter ursingii sp. nov. and Acinetobacter schindleri sp. nov., isolated from human clinical specimens. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 51:1891–1899. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-51-5-1891

Nemec A, Dijkshoorn L, Cleenwerck I et al (2003) Acinetobacter parvus sp. nov., a small-colony-forming species isolated from human clinical specimens. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 53:1563–1567. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.02631-0

Nemec A, Musílek M, Maixnerová M et al (2009) Acinetobacter beijerinckii sp. nov. and Acinetobacter gyllenbergii sp. nov., haemolytic organisms isolated from humans. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 59:118–124. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.001230-0

Nemec A, Musílek M, Šedo O et al (2010) Acinetobacter bereziniae sp. nov. and Acinetobacter guillouiae sp. nov., to accommodate Acinetobacter genomic species 10 and 11, respectively. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 60:896–903

Nemec A, Krizova L, Maixnerova M et al (2011) Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus–Acinetobacter baumannii complex with the proposal of Acinetobacter pittii sp. nov.(formerly Acinetobacter genomic species 3) and Acinetobacter nosocomialis sp. nov. (formerly Acinetobacter genomic species 13TU). Res Microbiol 162:393–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resmic.2011.02.006

Nemec A, Krizova L, Maixnerova M et al (2015) Acinetobacter seifertii sp. nov., a member of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex isolated from human clinical specimens. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 65:934–942. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.000043

Nemec A, Radolfova-Krizova L, Maixnerova M et al (2016) Taxonomy of haemolytic and/or proteolytic strains of the genus Acinetobacter with the proposal of Acinetobacter courvalinii sp. nov.(genomic species 14 sensu Bouvet & Jeanjean), Acinetobacter dispersus sp. nov.(genomic species 17), Acinetobacter modestus sp. nov., Acinetobacter proteolyticus sp. nov. and Acinetobacter vivianii sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 66:1673–1685

Nemec A, Radolfova-Krizova L, Maixnerova M, Sedo O (2017) Acinetobacter colistiniresistens sp. Nov. (formerly genomic species 13 sensu Bouvet and Jeanjean and genomic species 14 sensu Tjernberg and Ursing), isolated from human infections and characterized by intrinsic resistance to polymyxins. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 67:2134–2141. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijsem.0.001903

Nishimura Y, Ino T, Iizuka H (1988) Acinetobacter radioresistens sp. nov. Isolated from cotton and soil. Int J Syst Bacteriol 38:209–211. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-38-2-209

Parte AC (2018) LPSN—List of prokaryotic names with standing in nomenclature (Bacterio.net), 20 years on. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 68:1825–1829

Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL (2008) Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 21:538–582. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00058-07

Perichon B, Goussard S, Walewski V et al (2014) Identification of 50 class D β-lactamases and 65 Acinetobacter-derived cephalosporinases in Acinetobacter spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:936–949. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01261-13

Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP (2009) Fasttree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol Biol Evol 26:1641–1650. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msp077

Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP (2010) FastTree 2—Approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009490

Pulami D, Schauss T, Eisenberg T et al (2020) Acinetobacter baumannii in manure and anaerobic digestates of German biogas plants. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 96:fiaa176. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fiaa176

Radolfova-Krizova L, Maixnerova M, Nemec A (2016) Acinetobacter celticus sp. Nov., a psychrotolerant species widespread in natural soil and water ecosystems. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 66:5392–5398. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijsem.0.001526

Rafei R, Hamze M, Pailhoriès H et al (2015) Extrahuman epidemiology of Acinetobacter baumannii in Lebanon. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:2359–2367. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03824-14

Rice LB (2008) Federal funding for the study of Antimicrobial resistance in nosocomial pathogens: no ESKAPE. J Infect Dis 197:1079–1081. https://doi.org/10.1086/533452

Richter M, Rosselló-Móra R (2009) Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:19126–19131. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0906412106

Schauss T, Glaeser SP, Gütschow A et al (2015) Improved detection of extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli in input and output samples of German biogas plants by a selective pre-enrichment procedure. PLoS ONE 10:e0119791

Supaphol S, Jenkins SN, Intomo P et al (2011) Microbial community dynamics in mesophilic anaerobic co-digestion of mixed waste. Bioresour Technol 102:4021–4027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2010.11.124

Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ (1994) CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 22:4673–4680. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/22.22.4673

Tilley D, Law R, Warren S et al (2014) CpaA a novel protease from Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates deregulates blood coagulation. FEMS Microbiol Lett 356:53–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/1574-6968.12496

Touchon M, Cury J, Yoon EJ et al (2014) The genomic diversification of the whole Acinetobacter genus: origins, mechanisms, and consequences. Genome Biol Evol 6:2866–2882. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evu225

Towner K (2006) The Genus Acinetobacter. In: Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer KH, Stackebrandt E. (eds) The Prokaryotes, vol 6, 3rd edn. Springer, New York, NY, pp 746–758. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-30746-X_25

Turner S, Pryer KM, Miao VPW, Palmer JD (1999) Investigating deep phylogenetic relationships among cyanobacteria and plastids by small subunit rRNA sequence analysis. J Eukaryot Microbiol 46:327–338

Van Groenestijn JW, Deinema MH, Zehnder AJB (1987) ATP production from polyphosphate in Acinetobacter strain 210A. Arch Microbiol 148:14–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00429640

Vaneechoutte M, Nemec A, Musílek M et al (2009) Description of Acinetobacter venetianus ex Di Cello et al. 1997 sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 59:1376–1381. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.003541-0

Vaz-Moreira I, Novo A, Hantsis-Zacharov E et al (2011) Acinetobacter rudis sp. nov., isolated from raw milk and raw wastewater. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 61:2837–2843. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.027045-0027045-0

Visca P, Seifert H, Towner KJ (2011) Acinetobacter infection—an emerging threat to human health. IUBMB Life 63:1048–1054

Wentzel MC, Lotter LH, Loewenthal RE, Marais G (1986) Metabolic behaviour of Acinetobacter spp. in enhanced biological phosphorus removal - a biochemical model. Water SA 12:209–224

Yoon SH, Ha SM, Kwon S et al (2017) Introducing EzBioCloud: a taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 67:1613–1617. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijsem.0.001755

Zhou Y, Liang Y, Lynch KH et al (2011) PHAST: A fast phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res 39:W347–W352. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr485

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Sharmishtha Mishra for the performance of the cultivation approach during her master thesis. We thank Rita Kramer for excellent cooperation for sampling of input and output samples at the German biogas plants and Katja Grebing, Maria Sowinsky, Gundula Will, and Jan Rodrigues-Fonseca (Institute of Applied Microbiology, JLU Gießen) as well as Evelyn Skiebe (RKI) for excellent technical assistance.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Sampling and cultivation of the studied strains was performed as part of the project RiskAGuA (02WRS1274A) funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Germany. Dipen Pulami was supported by Postgraduate Scholarships from Justus Liebig University Giessen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DP and SG designed the study and wrote manuscript which was proofed by all co-authors. TS was responsible for the isolation of the strain. DP and SG performed molecular analysis; DP physiological tests. TE provided MALDI-TOF data, PK fatty acid data, JB and GW genome sequence data data, respectively. OS, JB, DP perfromed genome annotation and/or genome sequence based analyses.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

No specific permissions were required for these locations/activities and sampling was done with the agreement of the farmers.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession numbers of the 16S rRNA and rpoB/gyrB gene sequences of strain KPC-SM-21T are MT138756, MT157627 and MT157661, respectively. The GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession number of the whole genome shotgun sequence of strain KPC-SM-21T is OOGT00000000; the version described in this paper is version OOGT01000000. Supplementary figures and tables are provided in online supplementary materials.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pulami, D., Schauss, T., Eisenberg, T. et al. Acinetobacter stercoris sp. nov. isolated from output source of a mesophilic german biogas plant with anaerobic operating conditions. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 114, 235–251 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10482-021-01517-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10482-021-01517-7