Abstract

Fertility is highly determined by previous fertility intentions. Spain has one of the lowest levels of fertility in Europe. This work presents an analysis of fertility intentions in Spain based on data from the 2018 Fertility Survey conducted by the Spanish National Institute of Statistics. This survey identifies the key factors influencing recent and current fertility levels as well as the fertility intentions of its participants. Using the theoretical framework of the theory of planned behaviour and via multinomial logistic regression, the main social, economic and demographic factors that drive or inhibit desired fertility are determined and analysed. Traditional approaches rank the contribution of these factors or predictors to the dependent variable using a single criterion. In this work, several decision criteria will be simultaneously considered in the ranking of fertility intention’s predictors. The obtained results show how the costs of progression to paternity and the perceived benefits of having a child significantly impact decisions regarding first maternity. The demographic background factors that are related to age and the number of children are the determinants that most influence the second and subsequent maternities. The factors that are related to the labour market, gender roles and the negative effect of the current Spanish real estate market are also identified as determinants of desired fertility.

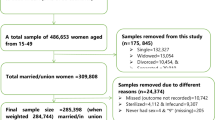

Source: Our elaboration based on the Spanish INE

Source: Our elaboration based on the Spanish INE

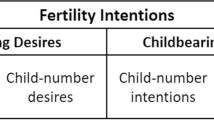

Source: Adapted from Ajzen and Klobas (2013)

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Acuña-Soto, C., Liern, V., & Pérez-Gladish, B. (2018). Normalization in TOPSIS based approaches with non-compensatory criteria: Application to the ranking of mathematical videos. Annals of Operations Research, available online,. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-018-2945-5.

Adsera, A. (2006). Marital fertility and religion in Spain, 1985 and 1999. Population Studies, 60(2), 205–221.

Adserà, A. (2017). The future fertility of highly educated women: The role of educational composition shifts and labor market barriers. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 15, 19–25.

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckman (Eds.), Action control: From cognition to behavior (pp. 11–39). Berlin: Springer.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Ajzen, I. (2005). Attitude personality and behaviour 2nd. New York: Open University Pres.

Ajzen, I. (2011). Is the theory of planned behavior an appropriate model for human fertility? Reflections on Morgan and Bachrach’s critique. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 9, 63–74.

Ajzen, I. (2012). The theory of planned behavior. In P. A. M. van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 438–459). London, UK: Sage Publications.

Ajzen, I., & Klobas, J. (2013). Fertility intentions: An approach based on the theory of planned behavior. Demographic Research, 29, 203–232.

Azen, R., & Traxel, N. (2009). Using dominance analysis to determine predictor importance in logistic regression. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 34(3), 319–347.

Becker, G. S. (1960). An economic analysis of fertility, demographic and economic change in developed countries: A conference of the Universities (pp. 209–231)., National Bureau Commitee for Economic Research Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Behzadian, M., Otaghsara, S. K., Yazdani, M., & Ignatius, J. (2012). A state-of the-art survey of TOPSIS applications. Expert Systems with Applications, 39(7), 13051–13069.

Berrington, A. (2004). Perpetual postponers? Women’s, men’s and couple’s fertility intentions and subsequent fertility behaviour. Population Trends, 117, 9–19.

Billari, F. C., Goisis, A., Liefbroer, A. C., Settersten, R. A., Aassve, A., Hagestad, G., et al. (2010). Social age deadlines for the childbearing of women and men. Human Reproduction, 26(3), 616–622.

Billari, F. C., Liefbroer, A. C., & Philipov, D. (2006). The postponement of childbearing in Europe: driving forces and implications. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 4, 1–17.

Billari, F. C., Philipov, D., & Testa, M. R. (2009). Attitudes, norms and perceived behavioural control: Explaining fertility intentions in Bulgaria. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 25(4), 439.

Blossfeld, H. P., & Huinink, J. (1991). Human capital investments or norms of role transition? How women’s schooling and career affect the process of family formation. American Journal of Sociology, 97(1), 143–168.

Bongaarts, J. (1994). The impact of population policies: Comment. Population and Development Review, 20(3), 616–620.

Bongaarts, J. (2001). Fertility and reproductive preferences in post-transitional societies. Population and development review, 27, 260–281.

Bongaarts, J. (2010). The causes of educational differences in fertility in Sub-Saharan Africa. Poverty, Gender, and Youth Working Paper no. 20. New York: Population Council. Version of record. https://doi.org/10.1553/populationyearbook2010s31.

Bongaarts, J. (2011). Can family planning programs reduce high desired family size in sub-Saharan Africa? International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 37(4), 209–216.

Brans, J. P., Vincke, P., & Mareschal, B. (1986). How to select and how to rank projects the PROMETHEE method. European Journal of Operational Research, 24, 228–238.

Brodmann, S., Esping-Andersen, G., & Güell, M. (2007). When fertility is bargained: Second births in Denmark and Spain. European Sociological Review, 23(5), 599–613.

Calvo, C., Ivorra, C., & Liern, V. (2016). Fuzzy portfolio selection with non-financial goals: exploring the efficient frontier. Annals of Operations Research, 245, 31–46.

Caplescu, R. (2014). Using the theory of planned behaviour to study fertility intentions in Romania. Procedia Economics and Finance, 10, 125–133.

Castro-Martín, T. (1995). Women’s education and fertility: results from 26 demographic and health surveys. Studies in Family Planning, 26(4), 187–202.

Castro-Martín, T. (2019). Maternidad (es) en el siglo XXI: una mirada desde la demografía. In Mujer, maternidad y Derecho (pp. 19–52). Tirant lo Blanch.

Castro-Martín, T., & Martín-García, T. (2013). Fecundidad bajo mínimos en España: pocos hijos, a edades tardías y por debajo de las aspiraciones reproductivas, en G. Esping-Andersen (coord.). El déficit de natalidad en Europa: la singularidad del caso español, Colección Estudios Sociales La Caixa, 36, 48–88.

Castro-Martín, T., & Seiz-Puyuelo, M. (2014) La transformación de las familias en España desde una perspectiva socio-demográfica en VII Informe sobre la exclusión y desarrollo social en España: Fundación FOESSA.

Chen, S. J., & Hwang, C. L. (1992). Fuzzy multiple attribute decision making methods and applications, 375. Berlin: Springer.

Churchman, C. W., & Ackoff, R. L. (1954). An approximate measure of value. Journal of the Operations Research Society of America, 2(2), 172–187.

Ciritel, A. A., De Rose, A., & Arezzo, M. F. (2019). Childbearing intentions in a low fertility context: The case of Romania. Genus, 75(1), 4.

Clarkberg, M., Stolzenberg, R. M., & Waite, L. J. (1995). Attitudes, values, and entrance into cohabitational versus marital unions. Social Forces, 74(2), 609–632.

Cooke, L. P. (2004). The gendered division of labor and family outcomes in Germany. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(5), 1246–1259.

Cooke, L. P. (2009). Gender equity and fertility in Italy and Spain. Journal of Social Policy, 38(1), 123–140.

Craig, L., & Siminski, P. (2011). If men do more housework, do their wives have more babies? Social Indicators Research, 101(2), 255–258.

De Laat, J., & Sevilla-Sanz, A. (2006). Working women, men’s home time and lowest-low fertility (No. 2006-23). ISER Working Paper Series.

Delgado, M. (2000). Los componentes de la fecundidad: su impacto en la reducción del promedio de hijos por mujer en España. Economistas, 18(86), 23–35.

Delgado, M. (2009). La fecundidad de las provincias españolas en perspectiva histórica. Estudios geográficos, 70(267), 387–442.

Devolder, D. (2015). Fecundidad: factores de la baja fecundidad en España. In España 2015: Situación social (pp 85–95). Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS).

Díaz-Fernández, M., Llorente-Marrón, M., & Méndez-Rodríguez, P. (2019). Interrelation between births and the housing market: A cointegration analysis for the Spanish case. Population, Space and Place, 25(2), e2172.

Dommermuth, L., Klobas, J., & Lappegård, T. (2011). Now or later? The theory of planned behavior and timing of fertility intentions. Advances in Life Course Research, 16(1), 42–53.

Esping-Andersen, G. (2017). Education, gender revolution, and fertility recovery. Vienna yearbook of population research, 15, 55–59.

Esteve, A., Devolder, D., & Domingo i Valls, A. (2016). La infecunditat a Espanya: Tic-tac, tic-tac, tic-tac!!! Perspectives Demogràfiques, 1, 1–4.

Estrella, A. (1998). A new measure of fit for equations with dichotomous dependent variables. Journal of business & economic statistics, 16(2), 198–205.

EUROSTAT (2019): Statistic Database Online, European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database. Last accessed January 29, 2019.

Fishbein, M. A., & Ajzen, I. (2011). I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behaviour: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, Addison-Wesley.

Frejka, T., & Westoff, C. F. (2008). Religion, religiousness and fertility in the US and in Europe. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 24(1), 5–31.

García-Melón, M., Pérez Gladish, B. M., Gómez-Navarro, T., & Méndez Rodriguez, P. (2016). Assessing mutual funds’ corporate social responsibility: a multistakeholder-AHP based methodology. Annals of Operations Research, 244(2), 475–503.

Gauthier, A. H. (2007). The impact of family policies on fertility in industrialized countries: a review of the literature. Population Research and Policy Review, 26(3), 323–346.

Gomes, L. F. A. M., & Lima, M. M. P. P. (1992). TODIM basics and application to multicriteria ranking of projects with environmental impacts. Foundations of Computing and Decision Sciences, 16(4), 113–127.

González-Ferrer, A., Castro-Martín, T., Kraus, E., & Eremenko, T. (2017). Childbearing patterns among immigrant women and their daughters in Spain: Over-adaptation or structural constraints. Demographic Research, 37, 599–634.

Green, P. E., Carroll, J. D., & DeSarbo, W. S. (1978). A new measure of predictor variable importance in multiple regression. Journal of Marketing Research, 15(3), 356–360.

Heiland, F., Prskawetz, A., & Sanderson, W. C. (2005). Do the more-educated individuals prefer smaller families? (No. 03/2005). Vienna institute of demography working papers.

Heiland, F., Prskawetz, A., & Sanderson, W. C. (2008). Are individuals’ desired family sizes stable? Evidence from West German panel data. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 24(2), 129–156.

Hiekel, N., & Castro-Martín, T. (2014). Grasping the diversity of cohabitation: Fertility intentions among cohabiters across Europe. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(3), 489–505.

Hwang, C. L., & Yoon, K. (1981a). Multiple attribute decision making: A state of the art survey. Lecture Notes in Economics and Mathematical Systems, 186, 1.

Hwang, C. L., & Yoon, K. (1981b). Multiple attribute decision making methods and applications a state of the art survey. Berlin: Springer.

Iacovou, M., & Tavares, L. P. (2011). Yearning, learning, and conceding: Reasons men and women change their childbearing intentions. Population and Development Review, 37(1), 89–123.

INE. (2018). Fertility survey. Madrid Spanish National Institute of Statistics. http://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/en/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736177006&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735573002. Last accessed February 22, 2019.

INE. (2019). Basic demographic indicators. https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/en/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736177003&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735573002. Last accessed January 09, 2019.

Johnson, J. W. (2001). Determining the relative importance of predictors in multiple regression: Practical applications of relative weights. Child Development, 59, 969–992.

Joshi, S., & Schultz, T. P. (2007). Family planning as an investment in development: Evaluation of a program’s consequences in Matlab (p. 951). Bangladesh: Yale University Economic Growth Center Discussion Paper.

Joshi, S., & Schultz, T. P. (2013). Family planning and women’s and children’s health: Long-term consequences of an outreach program in Matlab, Bangladesh. Demography, 50(1), 149–180.

Kalmijn, M. (2011). The influence of men’s income and employment on marriage and cohabitation: Testing Oppenheimer’s theory in Europe. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 27(3), 269–293.

Kraus, E. K., & Castro-Martín, T. (2018). Does migrant background matter for adolescents’ fertility preferences? The Latin American 1.5 generation in Spain. European Journal of Population, 34(3), 277–312.

Kravdal, Ø. (2002). Is the previously reported increase in second-and higher-order birth rates in Norway and Sweden from the mid-1970 s real or a result of inadequate estimation methods? Demographic Research, 6, 241–262.

Kreyenfeld, M., Andersson, G., & Pailhé, A. (2012). Economic uncertainty and family dynamics in Europe: Introduction. Demographic Research, 27, 835–852.

Kulu, H., & Steele, F. (2013). Interrelationships between childbearing and housing transitions in the family life course. Demography, 50(5), 1687–1714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0216-2.

Lamata, M. T., Liern, V., & Pérez-Gladish, B. (2018). Doing good by doing well: A MCDM framework for evaluating corporate social responsibility attractiveness. Annals of Operational Research, 267, 249–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-016-2271-8.

Lesthaeghe, R., & Van de Kaa, D. J. (1986). Two demographic transitions. Population: Growth and Decline, 1, 9–24.

Liefbroer, A. C. (2009). Changes in family size intentions across young adulthood: A life-course perspective. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 25(4), 363–386.

Llorente, M., & Díaz, M. (2014). Fecundidad y estructura familiar en España. Interciencia, 39(11), 1.

Mencarini, L., Vignoli, D., & Gottard, A. (2015). Fertility intentions and outcomes: Implementing the theory of planned behavior with graphical models. Advances in Life Course Research, 23, 14–28.

Miller, A. R. (2011). The effects of motherhood timing on career path. Journal of population economics, 24(3), 1071–1100.

Mills, M., Begall, K., Mencarini, L., & Tanturri, M. L. (2008). Gender equity and fertility intentions in Italy and the Netherlands. Demographic research, 18, 1–26.

Molyneaux, J. W., & Gertler, P. J. (2000). The impact of targeted family planning programs in Indonesia. Population and Development Review, 26, 61–85.

Morgan, S. P., & Rackin, H. (2010). The correspondence between fertility intentions and behavior in the United States. Population and Development Review, 36(1), 91–118.

Mulder, C. H. (2006). Population and housing: A two-sided relationship. Demographic Research, 15, 401–412.

Myrskylä, M., Kohler, H. P., & Billari, F. (2011). High development and fertility: Fertility at older reproductive ages and gender equality explain the positive link. Mpidr Working papers Wp-2011-017, Max planck institute for demographic research, Rostock Alemania.

OECD. (2007). Babies and bosses-reconciling work and family life: A synthesis of findings for OECD countries. París: OECD Publishing.

Peri-Rotem, N. (2016). Religion and fertility in Western Europe: Trends across cohorts in Britain, France and the Netherlands. European Journal of Population, 32(2), 231–265.

Philipov, D., Spéder, Z., & Billari, F. C. (2006). Soon, later, or ever? The impact of anomie and social capital on fertility intentions in Bulgaria (2002) and Hungary (2001). Population Studies, 60(3), 289–308.

Pritchett, L. H. (1994). The impact of population policies: Reply. Population and Development Review, 20(3), 621–630.

Régnier-Loilier, A., & Vignoli, D. (2011). Intentions de fécondité et obstacles à leur réalisation en France et en Italie. Population, 66(2), 401–431.

Rinesi, F., Pinnelli, A., Prati, S., Castagnaro, C., & Iaccarino, C. (2011). The transition to second child in Italy: Expectations and realization. Population, 66(2), 391–405.

Roy, B. (1968). Classement et choix en présence de points de vue multiples La méthode ELECTRE. Revue franfaise d’Informatique et de Recherche Operationnelle, 6(8), 57–75.

Roy, B. (1985). Méthodologie Multicritère d’aide à la Décision. Paris: Economica.

Sánchez-Barricarte, J. J., & Fernández-Carro, R. (2007). Patterns in the delay and recovery of fertility in Europe. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 23(2), 145–170.

Schoen, R., Astone, N. M., Kim, Y. J., Nathanson, C. A., & Fields, J. M. (1999). Do fertility intentions affect fertility behavior? Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61(3), 790–799.

Seiz, M. (2013). Voluntary childlessness in southern Europe: The case of Spain. Population Review, 52(1), 110–128.

Sevilla-Sanz, A. (2010). Household division of labour and cross-country differences in household formation rates. Journal of Population Economics, 23(1), 225–249.

Sobotka, T. (2004). Postponement of childbearing and low fertility in Europe. Amsterdam: Dutch University Press.

Ström, S. (2011). Childbearing behavior in the light of different housing regimes: First Births in Sweden 1975–2004. Stockholm University Linnaeus Center on Social Policy and Family Dynamics in Europe, SPaDE. Working Paper.

Symeonidou, H. (2000). Expected and actual family size in Greece: 1983–1997. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 16(4), 335–352.

Testa, M. R. (2012). Women’s fertility intentions and level of education: why are they positively correlated in Europe? European demographic research papers, 3, Vienna Inst. of Demography. Demography.

Thompson, D. (2009). Ranking predictors in logistic regression. Paper D10-2009. http://wwwmwsug.org/proceedings/2009/stats/MWSUG-2009-D10.pdf. Visited 2018, December 20.

Thornton, A., Axinn, W. G., & Xie, Y. (2008). Marriage and cohabitation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Toharia, L., & Villalón, J. C. (2005). El problema de la temporalidad en España: un diagnóstico (No. 80). Ministerio de Trabajo y Asuntos Sociales Subdireccion General.

Tonidandel, S., & LeBreton, J. M. (2010). Determining the Relative Importance of Predictors in Logistic Regression: An Extension of Relative Weight. Analysis Organizational Research Methods, 13(4), 767–781.

Toulemon, L., & Testa, M. R. (2005). Fertility intentions and actual fertility: A complex relationship. Population & Societies, 415(4), 1–4.

Triantaphyllou, E. (2000). Multi-criteria decision making a comparative study. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2013). World Fertility Report 2012 (United Nations publication).

Vignoli, D., Rinesi, F., & Mussino, E. (2013a). A home to plan the first child? Fertility intentions and housing conditions in Italy. Population, Space and Place, 19(1), 60–71.

Vignoli, D., Rinesi, F., & Mussino, E. (2013b). Un hogar para planificar el primer hijo? Intenciones de fertilidad y condiciones de vivienda en Italia. Población, espacio y lugar, 19, 60–71.

Wood, J., Neels, K., & Kil, T. (2014). The educational gradient of childlessness and cohort parity progression in 14 low fertility countries. Demographic Research, 31, 1365–1416.

Yamaguchi, K., & Ferguson, L. R. (1995). The stopping and spacing of childbirths and their birth-history predictors: Rational-choice theory and event-history analysis. American Sociological Review, 60, 272–298.

Yoon, K. P., & Hwang, C. L. (1995). Multiple attribute decision making an introduction. London: Sage Publications.

Zanakis, S. H., Solomon, A., Wishart, N., & Dublish, S. (1998). Multi-attribute decision making a simulation comparison of select methods. European Journal of Operational Research, 107(3), 507–529.

Zyoud, S. H., & Fuchs-Hanusch, D. (2017). A bibliometric-based survey on AHP and TOPSIS techniques. Expert Systems with Applications, 78, 158–181.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Llorente-Marrón, M., Díaz-Fernández, M. & Méndez-Rodríguez, P. Ranking fertility predictors in Spain: a multicriteria decision approach. Ann Oper Res 311, 771–798 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-020-03669-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-020-03669-7