Abstract

Miniaturization of biological and chemical assays in lab-on-a-chip systems is a highly topical field of research. The pressure-driven droplet-based microfluidic platform is a promising way to realize these miniaturized systems by expanding the capability of assays with special features that are unreached by traditional workflows. Full custom centric design of droplet-based microfluidic lab-on-a-chip systems leads to a high system integration level and design complexity. In our work, we report on a software toolkit based on the Kirchhoff laws for modeling droplet traffic and processing for even complex microfluidic networks. Experimental validation of the simulation results was performed utilizing directional droplet transport switching in a circular channel element. This structure can be employed as a benchmark system for the experimental validation of the obtained simulation results. As a result of these experiments, our design and simulation toolkit meet the requirements for a versatile and low-risk development of custom lab-on-a-chip devices. Together with our conceptual model of microfluidic networks, most of the development problems arising with complex lab-on-a-chip applications can be solved. Due to the high computational speed, the algorithm allows an interactive in silico evaluation of even complex sample-processing workflows in droplet-based microfluidic devices prior any preparation of prototypes. Summarizing the developed toolkit may become the foundation for the future development of software tools for a microfluidic design automation. As a result of this new way of simulation-based application-driven development, the advantages of lab-on-a-chip will be accessible for more people through the easy, versatile and efficient transformation from complex laboratory workflows to compact and easy to use lab-on-a-chip applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Albers A, Oerding J (2006) Product development regarding micro specific tasks. Microsyst Technol 16:1537–1545. doi:10.1007/s00542-010-1042-8

Boy DA, Gibou F, Pennathur S (2008) Simulation tools for lab on a chip research: advantages, challenges, and thoughts for the future. Lab Chip 8(9):1424–1431. doi:10.1039/16812596c

Engl W, Roche M, Colin A, Panizza P, Ajdari A (2005) Droplet traffic at a simple junction at low capillary numbers. Phys Rev Lett 95(20):208304. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.208304

Figeys D, Pinto D (2000) Lab-on-a-chip: a revolution in biological and medical sciences. Anal Chem 72(9):330A–335A. doi:10.1021/ac002800y

Fuerstman MJ, Garstecki P, Whitesides GM (2007) Coding/decoding and reversibility of droplet trains in microfluidic networks. Science 315(5813):828–832. doi:10.1126/science.1134514

Garstecki P, Fuerstman MJ, Stone HA, Whitesides GM (2006) Formation of droplets and bubbles in a microfluidic T-junction—scaling and mechanism of break-up. Lab Chip 6(3):437–446. doi:10.1039/B510841A

Gleichmann N et al (2008) Toolkit for computational fluidic simulation and interactive parametrization of segmented flow based fluidic networks. Chem Eng J 135(2008):S210–S218

Henkel T, Bermig T, Kielpinski M, Grodrian A, Metze J, Köhler JM (2004) Chip modules for generation and manipulation of fluid segments for micro serial flow processes. Chem Eng J 101(1–3):439–445. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2004.01.021

Labrot V, Schindler M, Guillot P, Colin A, Joanicot M (2009) Extracting the hydrodynamic resistance of droplets from their behavior in microchannel networks. Biomicrofluidics 3(1):012804

Link DR, Anna SL, Weitz DA, Stone HA (2004) Geometrically mediated breakup of drops in microfluidic devices rid b-6435-2008. Phys Rev Lett 92(5):054503

Malsch D (2014) Strömungsphänomene der Tropfenbasierten Mikrofluidik. Disseration, Technische Universität Ilmenau

Manz A, Graber H, Widmer HM (1990) Miniaturized Total Chemical Analysis Systems: A Novel Concept for Chemical Sensing. Sensor Actuator B-Chem 1(1–6):244–248. doi:10.1016/0925-4005(90)80209-I

Nagel LW (1973) SPICE (Simulation Program with Integrated Circuit Emphasis). Tech Rep EECS Department, University of California, Berkeley

Newton AR (1988) Twenty-five years of electronic design automation. Proc 25th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference, 2. DAC’88. Los Alamitos, CA, USA: IEEE Computer Society Press. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=285730.286213

Oh KW, Furlani EP (2012) Design of pressure-driven microfluidic networks using electric circuit analogy. Lab Chip 3(12):515–545

Panikowska K, Ashutosh T, Alcock J (2011) Towards service-orientation—the state of service thoughts in the microfluidic domain. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 56(1):135–142. doi:10.1007/s00170-011-3171-3

Reyes DR, Iossifidis D, Auroux PA, Manz A (2002) Micro total analysis systems. 1. Introduction, theory, and technology. Anal Chem 74(12):2623–2636. doi:10.1021/ac0202435

Seemann R, Herminghaus S (2012) Droplet based microfluidics. Reports on Progress in Physics (1/75) http://iopscience.iop.org/0034-4885/75/1/016601

Xize N, DeMello AJ (2012) Building droplet-based microfluidic systems for biological analysis. Biochem Soc Trans 4(40):615–623. doi:10.1042/BST20120005

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the BMBF in the projects DiNaMiD(0315591B/BMBF) and BactoCat (031A161A/BMBF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 (AVI 6449 kb)

Supplementary material 2 (AVI 1447 kb)

Appendices

Appendix 1: Linearization and solution of the equation system built from the microfluidic network

The equation system in matrix form contains the physical parameter space spanned by the microfluidic network. Preset by the user are the constraints \({\dot{V}_{A} ,\dot{V}_{B} ,\dot{P}_{C} }\). The calculation results will be held in the result vector’s elements \({P_{A} ,P_{2} ,P_{B} , { }P_{4} ,P_{5} ,P_{ 6} ,P_{ 7} ,\dot{V}_{C} }\) for each node, which represents an operation unit or a droplet. \(R_{a,b,c,d,e,f}\) represents the dynamic hydrodynamic resistance and \({\dot{V}_{ 2 , 4 , 5 , 6} }\) represents the calculated volume flow at each node.

The solution of the equation system in the bottom of Fig. 7 evaluates all parameters for the microfluidic network with the given hydrodynamic resistances \(R_{x}\). The problem is to find the correct values for \({R_{x} }\). As mentioned, the hydrodynamic resistance of droplets is not linear, but the linearity of the \({R_{x} }\) values is the basis of the nodal analysis algorithm. Figure 12a shows the nonlinear dependency of \(R\) for a droplet. Other parameters such as channel geometry, droplet complex length and fluid properties also influence the hydrodynamic resistance, but are considered as constant in this analysis. Only the relation between \({\dot{V}}\) and \(\Delta P\) is considered. The parameter \({R_{\text{linear}} }\), which is used to describe the network as system of equations, describes a linear dependency as seen in Fig. 12b. \({R_{\text{linear}} }\) is the slope given by the first derivative of the real hydrodynamic resistance function at the given point \({\Delta P_{w} }\). The second part of the algorithm finds a correct value for \({R_{\text{lin}} }\) and so the correct \({\varDelta P,\dot{V}}\) pair with the numerical methods.

(a) Example for the nonlinear dependency of resistance (R real) for a droplet complex. (b) the linearized resistance for the point w in iteration n is defined by the \({R_{\text{linear}}^{n} = \frac{{d\dot{V}\left( {\Delta P} \right)}}{{\Delta P}}\quad \hbox{at}\;P_{w} }\) \({\Delta P_{w} '}\) is the result solving the system matrix (Fig. 7). Its a new working point closer to the solution. \({R_{\text{linear}}^{n + 1} }\) is used as the new linearized resistance dependency in the next iteration n + 1

The algorithm starts with an initial guess for the resistance parameter \({R_{x} }\). This guess will be optimized iteration by iteration with the solution of the equation system generated an iteration before.

Every iteration step calculates new values for pressure drop and volume flow of each node, based on the approximation of the node’s hydrodynamic resistance. We applied the equation of the transport model, which is discussed earlier and shown in Fig. 12a, on these new values to get a new linear approximation of the hydrodynamic resistance. The error of the new approximation is smaller than before, because the new approximation point \({\Delta P_{w} }\) is closer to the final solution.

After some optimization steps, the algorithm finds an approximation for \({R_{x} }\) that fulfills the precision requirements. The result is a \({R_{x} = \frac{{\Delta P}}{{\dot{V}}}}\) value which matches the real nonlinear hydrodynamic resistance around the values \({\Delta P}\) and \({\dot{V}}\). The use of the equation system solved as matrix equation ensures that the pressure drop including the hydrodynamic resistance and the volume flow for all channels and droplets are optimized at once. At the end, all \({R_{x} }\) match the real hydrodynamic resistances at \({\Delta P_{x} }\) and \({\dot{V}_{x} }\).

The algorithm performs this optimization for all droplet complexes simultaneously. If the maximal error of the approximations is smaller than a predefined accuracy criterion, the calculation of the physical flow parameter \({\dot{V}}\) and \(P\) for each node is done.

Appendix 2: experimental validation system

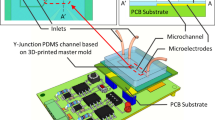

All-glass technology was selected for fabrication of the optical transparent microchannel system for validation. Half channels following the design in Fig. 13 were etched with hydrofluoric acid into glass substrates. A mask aligner aligned two of them. In the next step, an anodic bonding process merged two chip halves together with help of a bond support layer of 100 nm silicon. This layer was removed from the channel walls by etching, which provides the optical transparency for the micro channels.

The transport of the droplet sequences demands the cross section shown in Fig. 4 to avoid bypass flow of the separation fluid. An etch depth of 130 µm and a mask wide of 40 µm results in an almost circular channel profile. Its height is 260 µm, and its width is 300 µm.

A lubrication layer prevents direct contact between the dispersed phase and the microchannel walls. It is facilitated by hydrophobic surface functionalization using alkyl silanes.

The microfluidic chip is made for optimal optical access to the droplet content. It is 1.4 mm thick, and its planar dimensions are 25 mm × 16 mm. The length of the channels between the functional elements like injectors or bifurcation is given by the draft displayed in Fig. 13.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gleichmann, N., Malsch, D., Horbert, P. et al. Toward microfluidic design automation: a new system simulation toolkit for the in silico evaluation of droplet-based lab-on-a-chip systems. Microfluid Nanofluid 18, 1095–1105 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10404-014-1502-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10404-014-1502-z