Abstract

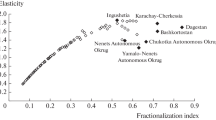

A number of developing countries have been experiencing high rates of ethnic fragmentation, corruption and political instability. The persistent poverty in many of these countries has led to an increased interest among both researchers and policy makers as to how these factors impact a country’s economic growth. Previous research has found mixed results as to whether ethnic fragmentation, corruption and political instability affect economic growth. However, this research has been focused on the direct impact of these variables on growth. This paper innovates by empirically modelling the impact of ethnic fractionalization and corruption on economic growth, both directly and indirectly through their role in affecting political stability. The analyses also add to the literature by testing a new data set with both fixed effects and GMM estimators. Results from a large panel data set of 157 countries from 1996–2014 finds that ethnic fractionalization and corruption negatively impact economic growth indirectly by increasing political instability, which has a negative direct effect on economic growth. Once the indirect effects are accounted for, ethnic fractionalization has no significant direct effect on growth. There is weak evidence to suggest that corruption may, in some countries, actually have a positive direct effect on growth by enabling firms to circumvent bureaucratic red tape, consistent with the “greasing the wheels” hypothesis. These results emphasize the importance of establishing strong institutions which are able to accommodate diverse groups and maintain political stability. Additional results find these implications to be particularly relevant for low-income and/or sub-Saharan African countries. The results also suggest that a country having a wide diversity of languages and religions need not be a hindrance to economic growth if a robust political system is in place.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For the sake of brevity, these results are available on request.

For the sake of brevity, the GMM results with 1791 observations are available on request.

References

Acemoglu D, Robinson J (2006a) Economic origins of dictatorship and democracy. Cambridge University Press, Boston

Acemoglu D, Robinson J (2006b) Economic backwardness in political perspective. Am Polit Sci Rev 100(1):115–131

Acemoglu D, Robinson J (2012) Why nations fail: the origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. Crown Business, New York

Ades AF, Glaeser EL (1999) Evidence on growth, increasing returns, and the extent of the market. Q J Econ 114(3):1025–1045

Alesina A, Devleeschauwer A, Easterly W, Kurlat S, Wacziarg R (2003) Fractionalization. J Econ Growth 8:155–194

Alesina A, La Ferrara E (2005) Ethnic diversity and economic performance. J Econ Lit 43:762–800

Alesina A, Ozler S, Roubini N, Swagel P (1996) Political instability and economic growth. J Econ Growth 1(2):189–211

Alesina A, Perotti R (1993) Income distribution, political instability, and investment. NBER Work Pap Ser 4486:1–33

Alesina A, Rodrik D (1994) Distributive politics and economic growth. Q J Econ 109(2):465–490

Alesina A, Spolaore E, Wacziarg R (2000) Economic integration and political disintegration. Am Econ Rev 90(5):1276–1296

Ali AB, Crain WM (2002) Institutional distortions, economic freedom, and growth. Cato J 21(3):415–426

Annett A (2001) Social fractionalization, political instability, and the size of government. IMF Staff Pap 48(3):561–592

Aschauer DA (1990) Why is infrastructure important? Fed Reserve Bank Boston Conf Ser 34:21–68

Ashraf Q, Galor O (2013) The ‘out of Africa’ hypothesis, human genetic diversity, and comparative economic development. Am Econ Rev 103(1):1–46

Barro RJ (1991) Economic growth in a cross-section of countries. Q J Econ 106(2):407–443

Barro RJ, Sala-i-Martin X (1995) Economic growth. McGraw-Hill, New York

Benhabib J, Spiegel MM (1994) The role of human Capital in Economic Development: evidence from aggregate cross-country and regional U.S. data. J Monet Econ 34(2):143–173

Blackburn K, Bose N, Haque ME (2010) Endogenous corruption in economic development. J Econ Stud 37:4–25

Blanco L, Grier R (2009) Long live democracy: the determinants of political instability in Latin America. J Dev Stud 45(1):76–95

Brander JA, Dowrick S (1994) The role of fertility and population in economic growth: empirical results from aggregate cross-National Data. J Popul Econ 7(1):1–25

Chew J (2016) These Are the Most Corrupt Countries in the World http://fortune.com/2016/01/27/transparency-corruption-index/

Collier P, Hoeffler A (1998) On economic causes of civil war. Oxf Econ Pap 50(4):563–573

Collier P (2000) Ethnicity, politics, and economic performance. Econ Polit 12(3):225–245

Collier P (2001) Ethnic diversity: an economic analysis. Econ Policy 32:129–166

Davoodi HR, Tanzi V (1997) Corruption, public investment, and growth. IMF Work Pap 97(139):1–23

Dawson JW (2003) Causality in the freedom-growth relationship. Eur J Polit Econ 19(3):479–495

De Haan J, Siermann CLJ (1995) A sensitivity analysis of the impact of democracy on economic growth. Empir Econ 20(2):197–215

De Haan J, Siermann CLJ (1996) New evidence on the relationship between democracy and economic growth. Public Choice 86(1):175–198

Desmet K, Ortuno-Ortin I, Wacziarg R (2015) Culture, ethnicity and diversity. NBER working paper no. 20989. National Bureau of economic research. Cambridge

Easterly W, Levine R (1997) Africa’s growth tragedy: policies and ethnic divisions. Q J Econ 112(4):1203–1250

Easterly W (2001) Can institutions resolve ethnic conflict? Econ Dev Cult Chang 49(4):687–706

Esteban J, Ray D (1994) On the measurement of polarization. Econometrica 62(4):819–851

Goren E (2014) How ethnic diversity affects economic growth. World Dev 59:275–297

Kimenyi MS (2006) Ethnicity, governance and the provision of public goods. J Afr Econ 15(1):62–99

La Porta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F, Shleifer A, Vishny R (1999) The quality of government. J Law, Econ Org 15(1):222–279

Levine R, Renelt D (1992) A sensitivity analysis of cross-country growth regressions. Am Econ Rev 82(4):942–963

Mauro P (1995) Corruption and growth. Q J Econ 110:681–712

Mo PH, Papyrakis E (2014) Fractionalization, polarization, and economic growth: identifying the transmission channels. Econ Inq 52(3):1204–1218

Montalvo JG, Reynal-Querol M (2005) Ethnic polarization, potential conflict, and civil wars. Am Econ Rev 95(3):796–816

Mulligan CB, Gil R, Sala-i-Martin X (2004) Do democracies have different public policies than nondemocracies? J Econ Perspect 18(1):51–74

Nelson RR, Phelps ES (1966) Investment in Humans, technological diffusion, and economic growth. Am Econ Rev 56(1/2):69–75

Piatek D, Szarzec K, Pilc M (2013) Economic freedom, democracy, and economic growth: a causal investigation in transition countries. Post-Communist Econ 25(3):267–288

Ranis G (2009) Diversity of communities and economic development. Yale Univ Econ Growth Center 977:1–17

Reynal-Querol M (2002) Ethnicity, political systems, and civil wars. J Confl Resolut 46(1):29–54

Roe J, Siegel J (2011) Political instability: effects on financial development, roots in the severity of economic inequality. J Comp Econ 39(3):279–309

Sasaoka Y (2007) Decentralization and conflict. Japanese International Cooperation Agency, 889th Wilton Park conference, pp 1–30

Transparency International (2015) Corruption Perception Index 2015. http://www.transparency.org/cpi2015. Accessed July 2016

World Bank (2016a) Anti-Corruption http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/governance/brief/anti-corruption. Accessed July 2016

World Bank (2016b) Poverty: Overview http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/overview. Accessed July 2016

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

The 2SLS model was run for the full sample of countries, both with and without the Gini index. The results in the body of the paper excluded the Gini Index. When including the Gini index, the sample only consisted of 754 observations, compared to 1791 observations when excluding the Gini index. When run with the Gini, corruption is found to affect instability, but neither measure of fractionalization nor the Gini index is significant. Religious fractionalization significantly impacts GDP growth, only at the 10% level, and neither political instability nor the Gini index has a significant impact on GDP growth. This does not agree with the findings in the literature. The inclusion of the Gini index may be impacting results as it dramatically lowers the sample size (Tables 4 and 5).

Appendix 2

This appendix contains results with both additional variables and another empirical methodology. A country’s openness to international trade may have a significant impact on its economic growth (Ades and Glaeser 1999; Alesina et al. 2000). In order to test the impact of these factors and to check robustness of the other results, analyses including openness is included in the tables below. These tables include a variable for openness (trade/GDP). The tables below also include a variable representing economic freedom. Tables 6 and 7 contain results using the fixed effect methodology in the body of the paper with these additional variables. An interaction term for openness and initial GDP per capita was also tested but was insignificant so not included in the results. Tables 8 and 9 test these additional variables using a GMM methodology. One of the weaknesses of a 2SLS or similar type of regression analysis is its reliance on functional form. As an additional test of robustness, a generalized method of moments (GMM) methodology is employed on the data. Its usage in this case helps to show that the results are not contingent to specific assumptions regarding functional form.

There is some loss of observations when adding the additional variables. These additional analyses have 1553 observations as opposed to the 1791 observation from the results in the body of the paper. It is worth noting a few differences in the results. One substantial difference in the fixed effects analyses is corruption having a positive direct impact on economic growth. This was consistent with some of the subsample analysis but not with the 1791 observation full sample results (in which corruption’s direct effect was insignificant). For the GMM analysis, the direct impact of corruption on economic growth was insignificant. A relevant difference in the GMM results is the significant, positive effect of instability on economic growth. This occurs in the 1553 observation sample run with GMM. However, instability becomes insignificant if GMM is run with the full 1791 observation sample.Footnote 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Karnane, P., Quinn, M.A. Political instability, ethnic fractionalization and economic growth. Int Econ Econ Policy 16, 435–461 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-017-0393-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-017-0393-3