Abstract

The strategy of migrants crossing the Sahara desert has been the subject of debate, but recent evidence from radar studies has confirmed that most passerines use an intermittent migration strategy. The latter has also been suggested from previous studies in oases during autumn migration. It was found that migrants with relatively high fuel loads rest in the desert during daytime and continue migration during the following night, whereas lean migrants stopover in oases for several days to refuel. However, data from the Sahara are scarce for spring migration. We captured passerine migrants near Bîr Amrâne (22°47′N, 8°43′W) in the plain desert of Mauritania for 3 weeks during spring migration in 2004. We estimated flight ranges of 85 passerines stopping over in the desert to test whether they carried sufficient fuel loads to accomplish migration across the Sahara successfully. High fat loads of the majority of birds indicated that they were neither “fall-outs” nor too weak to accomplish migration successfully. The flight range estimates, based on mean flight speeds derived from radar measurements (59 km/h), revealed that 85% of all birds were able to reach the northern fringe of the desert with an intermittent migration strategy. Furthermore, birds stopping over in an oasis (Ouadâne, 370 km to the southwest of Bîr Amrâne) did not carry consistently lower fuel loads compared to the migrants captured in the desert.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Moreau (1961, 1972) suggested that passerines on autumn migration cross the Mediterranean Sea and the Sahara desert in a 40- to 60-h nonstop flight. Evidence assumed to support this non-stop theory was that migrants do not concentrate in oases, that, e.g., flycatchers (Muscicapidae) are hardly observed on the south Mediterranean coast in autumn, and that grounding should be avoided because of the danger of evaporative water loss (Moreau 1961, 1972). Furthermore, numbers of birds found in the desert during daytime were regarded as being comparatively low compared to the total number of migrants estimated by Moreau (Wood 1989). This non-stop hypothesis was challenged by Bairlein (1985, 1992) and Biebach et al. (1986, 1991) who proposed an alternative intermittent strategy that involves regular stopovers in the desert and in oases. The main argument for an intermittent migration strategy was that an unexpectedly high proportion of passerines grounded in oases were in good physical condition with sufficient fuel stores to continue migration (Bairlein et al. 1983; Bairlein 1992; Biebach 1995). They are therefore not “fall-outs” as hypothesized by Moreau (1972). Non-stop and intermittent strategies were not seen as mutually exclusive (Bairlein 1992; Bruderer 1994; Biebach 1995; Biebach et al. 2000). Recently, Schmaljohann et al. (2007a) showed that most passerines use an intermittent flight strategy, but that at least in spring nocturnal migrants prolong migration into the day when wind conditions are favourable (Schmaljohann et al. 2007b).

Investigations on fat stores and potential flight ranges of migrants in the desert (Bairlein 1985, 1988; Biebach et al. 1986) were mainly performed in oases or vegetated wadis and only during autumn migration. As it is known for some species that they spend less time on spring migration compared to autumn (Pearson 1992; Berthold 2001), they might also use a different strategy with respect to stopover ecology to cross the desert on their way towards the breeding grounds (Salewski and Schaub 2007).

We spent 18 days at Bîr Amrâne, a site in the plain desert of Mauritania, in April 2004 and caught birds in a small sparsely vegetated patch. As most migrants use an intermittent strategy on spring migration (Schmaljohann et al. 2007a), we tested the hypotheses that: (1) migrants grounded in the desert carry fat loads that indicate they are not “fall-outs”, i.e. not too exhausted to continue migration; (2) we compared the data with those collected in an oasis during the same period and tested whether birds grounded in the desert carry more fuel stores than birds stopping over in the oasis; and finally (3) we tested what proportion of migrants grounded in the desert carry sufficient fuel loads to accomplish the desert crossing successfully without refuelling.

Methods

Study site

The study was performed near the temporary settlement of Bîr Amrâne (22°47′N, 8°43′W), Mauritania, between 6 and 24 April 2004. About 20 km NW of Bîr Amrâne is a stand of ca.20 Acacia raddiana trees with a height of about 3–5 m. The next scattered trees are found ca.230 km SW of the study site near El Ghallâouîya (21°35′N, 10°35′W), and the next small wood (Acacia raddiana, A. ehrenbergiana, Maerua crassifolia, Capparis decidua, Ziziphus lotus) is 260 km SW of Bîr Amrâne. According to our very reliable guide, there are no other trees or bushes around Bîr Amrâne for at least several hundred kilometres to the west, north and east (Salem, personal communication.). We therefore assume that the nearest region where migrants may refuel after the desert crossing is the Anti Atlas of Morocco approximately 800 km to the north. The Mediterranean coast is approximately 1,500 km north of Bîr Amrâne.

The study site was situated in a small sandy depression in stony desert about 3 km south of Bîr Amrâne. Birds were mist-netted in an area of about 1.5 ha with scattered clumps of the grass Aristida pengens and of Pergularia tomentosa, both growing to a maximum height of 1.5 m. Another similar patch was situated nearby. To our knowledge, there was no other such vegetation in a surrounding of dozens of kilometres. Mistnetting also took place regularly 370 km to the SW, in the oasis of Ouadâne (20°54′N, 11°35′W), during the same period. There birds were captured between sparse Acacia raddiana, Balanites aegyptiaca and Maerua crassifolia trees (Salewski and Schaub 2007).

Data collection

Birds were caught by placing standard 6-m-long nist-nets over 19 single bushes so that about three-quarters of the sides and the top of the bushes were covered. On the open side of the bush, the net was lifted with a pole to form a triangle shaped entrance into the bush. On the ground, the nets were fixed with pegs and dug into the sand to prevent birds escaping by lifting the net. The construction allowed birds to enter the bush from only one side. Additionally, we placed two larger nets (10 × 8 m) over two bushes each. We walked around the site at regular intervals throughout the day and approached all netted bushes from the side of the net entrance. On reaching the bush, it was beaten with a stick because many birds did not otherwise move. Usually, birds trying to escape got entangled in the net. During this procedure, all bushes without nets were also beaten in order to chase birds into bushes with nets. In the great majority of cases, this was successful, because flushed birds usually sought refuge in a nearby bush. Thus, only a few birds escaped after arriving in the study area and most birds were caught within 1 h after arrival. Escaping birds were mainly Woodchat Shrikes Lanius senator, which perched on the bushes or on the nets and their supporting poles. As birds were chased out of all potential resting sites (grass, bushes), there was no bias caused by potentially higher inactivity of birds with high fuel loads compared to those with low fuel loads (Bibby et al. 1976; Bairlein 1987; Titov 1999).

All birds were ringed immediately after capture with an aluminium ring and an individual combination of three colour rings, and standard measurements were taken. Fat scores were estimated after Kaiser (1993) and classified between 0 (no fat) and 8 (ventral parts completely covered with fat). Body mass was taken with an electronic balance with an accuracy of 0.1 g. During the net-controls, birds observed were checked for colour rings and a search for birds with colour rings was performed in the patch of vegetation nearby twice a day.

Flight range estimation

To estimate flight ranges, we assumed that flying birds lose mass at a constant rate of 1% per hour flight time when evaporative heat loss is not actively increased (Hussel and Lambert 1980; Kvist et al. 1998). Following Delingat et al. (2008), we estimated the potential flight range Y (km) according to the equation:

U (km/h) is the groundspeed of the migrating birds. In contrast to Delingat et al. (2008), we did not use airspeed for the estimation of flight ranges. Passerines select the flight altitude with the most favourable winds (Liechti 2006; Liechti and Schmaljohann 2007a; Schmaljohann et al. 2008), and the distance covered with respect to the ground is expressed by the groundspeed which is a function of the airspeed and the tailwind component. We therefore used groundspeed to estimate flight ranges. The mean groundspeed of 931 nocturnally migrating passerines tracked with a tracking radar in Ouadâne from 6 to 24 April 2004 (cf. Schmaljohann et al. 2007b; Swiss Ornithological Institute, unpublished data) was 16.3 ± 5.8 m/s (SD), which can be transformed to approximately 59 ± 21 km/h (SD). Mean groundspeed was 37% higher than mean airspeed. f is the relative fuel load derived from:

where m is the body mass of the captured birds and m 0 the body mass of birds without fuel. We refrain from using the term “lean mass” because it is usually used for birds without fat fuel, but ignores the fact that birds also use protein as fuel for migration (Jenni and Jenni-Eiermann 1998). Therefore, we applied the concept of structural mass following Salewski et al. (2009) for birds without fuel. According to the concept of structural mass, m0 is close to the mass of birds with both a fat score and a muscle score of 0. To estimate the flight range of every individual bird, m0 was corrected for size. For the size correction, we first selected all birds nist-netted with a fat score and a muscle score of 0 during the Swiss Ornithological Institute’s project between 2001 and 2004 on bird migration across the Sahara (Liechti and Schmaljohann 2007b). The great majority of these birds did not appear to be moribund, and retraps and recoveries in Europe show that even extremely low body masses were reversible (V. Salewski et al., unpublished data). A regression function of the body mass on the third outermost primary of those birds was applied to estimate m0 of the birds considered in this study according to:

where β0 is the intercept and β1 a constant from the regression. For several species, i.e. Rufous Bush Robin Cercotrichas galactotes, Northern Wheatear Oenanthe oenanthe, Black-eared Wheatear O. hispanica, Reed Warbler Acrocephalus scirpaceus, Olivaceous Warblers [Hippolais (pallida) opaca and Hippolais pallida reiseri were treated as one species], Orphean Warbler Sylvia hortensis, Subalpine Warbler S. cantillans, Golden Oriole Oriolus oriolus and Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, only five or fewer individuals with both fat and muscle scores of 0 were nist-netted. For these, the arithmetic mean of the mass of the individuals captured with both fat score and muscle score 0 was used for m0 to estimate flight ranges. This was also the case for the Yellow Wagtail Motacilla flava because the respective regression slope was negative.

Two approaches were used to estimate whether birds were able to cross the remaining part of the desert. First, potential flight ranges were estimated according to Eq. 1, without taking into account any diurnal stopovers or higher flight costs with respect to energy and water expenditure during the day. Second, accepting that most birds use an intermittent flight strategy to cross the desert, we assumed that birds migrate from about 2000 to 0600 hours, based on results of a radar study (Schmaljohann et al. 2007a). Therefore, potential migratory ranges were estimated under the assumption that passerines fly for 10 h in the night and rest for 14 h during the day. During diurnal resting, 0.5% of body mass is assumed to be lost per hour (Meijer et al. 1994; J. Delingat, V. Dierschke, H. Schmaljohann and F. Bairlein, unpublished data). The duration of the first remaining resting period at the study site was taken as the time from the full hour after release of the captured bird to 2000 hours. Statistical tests were calculated with SPSS 12.0, and P ≤ 0.05 was used as the criterion for statistical significance.

Results

Body condition

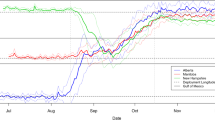

Eighty-five Palearctic passerine migrants of 20 species were caught in Bîr Amrâne (Table 1). A Subalpine Warbler and a Garden Warbler Sylvia borin were recaptured after 1 day and a Melodious Warbler Hippolais polyglotta after 2 days. None of the colour ringed birds was resighted. Of the captured birds, 70 belonged to 9 species of which 4 or more individuals were captured. The median fat scores of these species varied between 2 (Willow Warbler Phylloscopus trochilus) and 5 (Orphean Warbler, Garden Warbler; Fig. 1). Two species had a median score of 3 (Melodious Warbler, Woodchat Shrike), the remaining species median scores of 4 and 4.5, respectively. Within species, individual scores ranged from 1 to 6 (Common Whitethroat Sylvia communis) and from 1 to 5 (Willow Warbler) or were restricted to only two values (4 and 5 in Orphean Warbler, 5 and 6 in Garden Warbler). For species of which only one or two individuals were captured, the fat scores were: Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica, 2; Yellow Wagtail, 4 and 5; Tree Pipit Anthus trivialis, 0; Rufous Bush Robin, 4; Common Redstart Phoenicurus phoenicurus, 0; Northern Wheatear, 1; Black-eared Wheatear, 3; Sedge Warbler Acrocephalus schoenobaenus, 3; Reed Warbler, 3 and 3; Golden Oriole, 5; and Ortolan Bunting, 3. These values indicate that passerine migrants grounded during spring migration in the desert are not generally “fall-outs” that are too weak to continue migration, although some individuals did show low fat scores.

Sample sizes of Melodious Warbler, Subalpine Warbler and Common Whitethroat were large enough to compare their body conditions with those mist-netted at the same period in Ouadâne (Fig. 2). The median fat scores of birds from Ouadâne were 6, 4 and 5 for Melodious Warbler (n = 21), Subalpine Warbler (n = 16) and Common Whitethroat (n = 26), respectively. The median was significantly higher in Ouadâne compared to Bîr Amrâne for Melodious Warbler (median test: χ 2 = 6.751, P = 0.009) and nearly significantly higher for Common Whitethroat (χ 2 = 3.688, P = 0.055). Subalpine Warblers had higher median fat scores in the desert, but the difference was not significant (median test: χ 2 = 0.097, P = 0.756). Similarly, body mass was significantly higher in the oasis than at the desert site for Melodious Warblers (oasis: 12.97 ± 1.24 g, n = 21; desert: 11.54 ± 0.79 g, n = 8; t test: t 27 = −3.023, P = 0.005) and for Common Whitethroats (oasis: 17.93 ± 1.47 g, n = 26; desert: 16.21 ± 1.81 g, n = 14; t test: t 38 = −3.246, P = 0.002). Subalpine Warblers in the oasis also had a higher mean body mass than those in the desert, but the difference was not significant (oasis: 10.85 ± 1.38 g, n = 15; desert: 10.02 ± 1.34 g, n = 10; t test: t 23 = −1.486, P = 0.151). Hence, we cannot confirm that migrants captured in the desert during spring migration have higher fuel loads compared to migrants resting in an oasis.

Flight ranges

Flight ranges could be estimated for 83 individual migrants. For one Olivaceous Warbler and one Common Whitethroat, body mass was not available. Most birds captured at Bîr Amrâne carried enough fuel to cross the desert and the majority were even able to reach the Mediterranean (Table 1). When an average groundspeed of 59 km/h is assumed, 96% of all birds carry enough fuel to reach the Anti Atlas without refuelling. Only 1 of 16 Willow Warblers as well as the only captured Tree Pipit and Common Redstart would not have been able to cross the desert without further refuelling or with more favourable wind conditions.

As passerines cross the Sahara desert with an intermittent flight strategy (Schmaljohann et al. 2007a), fuel is not only expended for nocturnal flights but also for diurnal rest. When diurnal fuel loss is accounted for, the majority of birds would still have been able to cross the desert with the actual fuel load given an average groundspeed. If we omit the two captured Barn Swallows and the Yellow Wagtail, because these species also migrate during the day and the Swallow may be able to forage on migration, we estimated the migratory ranges of 80 birds. Assuming an average groundspeed of 59 km/h, 68 migrants (85%) would have been able to reach the Anti Atlas in southern Morocco (Table 1). The majority of passerines captured in Bîr Amrâne were therefore able to cross the Sahara without refuelling.

Discussion

Migrants with relatively high fat scores occurred in the desert far away from oases or other apparently more favourable stopover sites. Because of the capture method, data are not influenced by different capture probabilities associated with different fuel loads and are representative samples of birds that have deliberately come to ground at the study site. In contrast to Moreau’s (1972) suggestion, the majority of migrants carried relatively high fuel loads and cannot therefore be seen as “fall-outs” that are in too poor a physiological condition to continue migration.

Migrants in the oasis of Ouadâne tended to carry larger fuel loads and to have higher body masses than birds in the desert during the same period. This is in contrast to the study of Biebach et al. (1986). There, it was argued that birds with sufficient fuel for migration rest in the desert during daytime and continue migration during the next night, whereas lean birds were supposed to stop over in oases, where they may refuel for several days. Due to the low number of recaptures, we were not able to estimate stopover duration using capture–recapture models. Nevertheless, we assume that the low number of recaptures and resightings indicates that captured birds resumed migration the following night irrespective of the actual fuel load. This is in contrast to the oasis of Ouadâne where average estimated stopover durations ranged from 7 days (Woodchat Shrike) to 14 days (Eastern Olivaceous Warbler; Salewski and Schaub 2007) and daily fuel deposition rates were significantly positive for many species (unpublished data). We therefore assume that migrants in the desert carried less fuel because they had already spent some energy on migration without the possibility of refuelling at our study site.

Most migrants landing in the desert will be able to continue migration successfully. This supports former capture studies in autumn showing that migrants cross the Sahara with an intermittent flight strategy (Bairlein 1985; Biebach et al. 1986) and confirms radar observations from spring at the study site (Schmaljohann et al. 2007a). The proportion of potentially successful birds was probably even a conservative estimation for the following reasons. First, the fuel load of the captured birds was underestimated. The birds which were considered for the estimation of m 0 were still alive and did not appear to be moribund. Therefore, they still had some fuel left, i.e. their body mass may have been close, but still above the definition of the structural mass m 0 (Swiss Ornithological Institute, unpublished data). Second, the assumption of 1% loss of body mass per hour migration may have been too general (Delingat et al. 2008). Hussel and Lambert (1980) found mean losses of body mass varying between 0.33 and 1.64% per hour flight in North American migrants. The mean body mass loss across nine species (excluding Blackpoll Warbler Dendroica striata with a mean rate of mass change of −0.06% per hour) was 1.0% per hour flight or 0.91% for a hypothetical bird of 18.9 g derived from a regression of the logarithmic transformed data. The rate of body mass loss was positively related to body mass. Therefore, we may have overestimated the rate of body mass loss for the smaller species, e.g. Willow Warblers and Subalpine Warblers in this study. Third, it was assumed that birds rest during 14 h per day from 0600 to 2000 hours, but Schmaljohann et al. (2007b) showed that under favourable wind conditions a proportion of birds prolong their migratory flight for some hours into the day during spring migration. Under these circumstances migrants will spend more fuel for actual migration under favourable conditions compared to “wasting” fuel for resting. Fourth, the models assumed that there is no possibility for refuelling during the desert crossing. There were some large locusts at the study site and Woodchat Shrikes were observed foraging on them indicating that at least this species and possibly also wheatears may be able to forage on migration. Apart from some small moths, no other insects were observed at the study site (personal observation), but there is still the possibility that the desert is not completely devoid of food as usually assumed.

It is surprising that according to our estimates even birds with relatively low fuel loads, e.g. with a fat score of 1 or 2, would still have been able to accomplish migration across the desert without refuelling. The difference between our study and former investigations is that we account for wind support (real groundspeeds) and that the m0 used here is distinctly lower for all species for which there are data available than the “lean body mass” used by previous authors. Taking the Garden Warbler and the Common Whitethroat as examples, the mean body mass of individuals nist-netted during the entire project on bird migration across the Sahara with both a fat score and a muscle score of 0 was 12.8 g (±0.09 SD, n = 121) and 10.9 g (±0.23 SD, n = 17), respectively (Swiss Ornithological Institute, unpublished data). Previous studies calculated potential flight ranges using 14.8 g or 16.1 g for as lean body mass for the Garden Warbler (Pilastro and Spina 1997; Hilgerloh and Wiltschko 2000) and 12.2 g or 12.9 g for Common Whitethroat (Pilastro and Spina 1997; Ottosson et al. 2001). The difference will lead to higher estimated flight ranges for birds with larger fuel loads such as the birds in this study. This has implications for our view of stopover and refuelling strategies prior to the desert crossing. Moreau (1972) wondered how the majority of migrants are able to accumulate sufficient fuel stores to cross the desert on spring migration just at its southern fringe during a time when the dry season is at its peak and food abundance is thought to be low, a phenomenon which was later called Moreau’s paradox (Mead 1972). A partial solution of this paradox may be that migrants carry sufficient fuel stores to cross the desert, although this may not be indicated by exceptional high fat scores.

The estimated flight range of migrants is higher when a non-stop flight is assumed compared to an intermittent migration strategy, because for the latter fuel is also consumed during resting periods. Therefore, there is an apparent discrepancy between an intermittent flight strategy and the need to cross the desert with limited resources without the possibility of refuelling. During the night, air layers are laminar, the temperature is lower and relative humidity higher than during the day. Flying in laminar air layers at night is less energy demanding than flying in turbulent air during the day (Kerlinger and Moore 1989). Though some passerines prolonged their migratory flights into the day, they did so only at very high altitudes (3,000 m above ground level; Schmaljohann et al. 2007b) and only until midday under favourable tailwind conditions. Later in the day, turbulence might have built up even at this altitude. Strikingly, hardly any passerines prolonged their migratory flight into the day in autumn (Schmaljohann et al. 2007a). This may be due to the fact that in autumn favourable wind conditions occur only at low altitudes which coincide with turbulent air, high temperatures and low humidity (Schmaljohann et al. 2008). Furthermore, passerines may experience excessive water loss when flying during the day through hot and dry air (Carmi et al. 1992; Leger and Larochelle 2006). Although the exact energy expenditure and water loss of passerines when crossing the Sahara are still unknown, the advantages of nocturnal flights and diurnal rest with respect to energy expenditure are likely to prevent the majority of passerines from crossing the Sahara non-stop.

Zusammenfassung

Im Frühjahr in der Sahara rastende Singvögel sind keine Ausfälle

Die Strategie die Zugvögel anwenden um die Sahara zu überqueren war lange umstritten. Neuere Radarstudien belegen jedoch, dass sie intermittierend ziehen. Dies wurde auch schon aufgrund von Studien in Oasen für den Herbstzug vorgeschlagen. Zugvögel mit einem relativ hohen Anteil an Reserven rasteten während des Tages in der Wüste und setzten den Zug in der nächsten Nacht fort. Magere Vögel rasteten dagegen mehrere Tage in Oasen um Nahrung aufzunehmen. Daten aus der Sahara während des Frühjahrszuges liegen dagegen kaum vor. Wir fingen Zugvögel für drei Wochen während des Frühjahrszug 2004 nahe Bîr Amrâne (22°47′N, 8°43′W) in der Sahara in Mauretanien. Wir schätzten die potentiellen Zugdistanzen von 85 Singvögeln die in der Wüste rasteten. Dadurch sollte getestet werden, ob sie über genug Reserven verfügen um den Zug über die Sahara erfolgreich abzuschließen. Hohe Fettreserven zeigten, dass sie keine Ausfälle waren, die zu schwach sind um den Zug erfolgreich fortzusetzen. Die Schätzungen der potentiellen Flugdistanzen, basierten auf einer durchschnittlichen Zuggeschwindigkeit von 59 km/h, die durch Radaruntersuchungen ermittelt wurde. Sie ergaben, dass 85% aller Vögel in der Wüste über genügend Reserven verfügten um ohne weitere Nahrungsaufnahme den Nordrand der Sahara erreichen zu können, wenn sie eine intermittierende Zugstrategie anwenden. Darüber hinaus verfügten Zugvögel, die in einer Oase (Ouadâne, 370 km südwestlich von Bîr Amrâne) rasteten, nicht generell niedrigere Reserven als die, die in der Wüste gefangen wurden.

References

Bairlein F (1985) Body weights and fat deposition of Palearctic passerine migrants in the central sahara. Oecologia 66:141–146

Bairlein F (1987) Nutritional requirements for maintenance of body weight and fat deposition in the long-distance migratory garden warbler, Sylvia borin (Boddaert). Comp Biochem Physiol 86:337–347

Bairlein F (1988) Herbstlicher Durchzug, Körpergewichte und Fettdeposition von Zugvögeln in einem Rastgebiet in Nordalgerien. Vogelwarte 34:237–248

Bairlein F (1992) Recent prospects on trans-Saharan migration of songbirds. Ibis 134:41–46

Bairlein F, Beck P, Feiler W, Querner U (1983) Autumn weights of some palaearctic passerine migrants in the Sahara. Ibis 125:404–407

Berthold P (2001) Bird migration. A general survey. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Bibby CJ, Green RE, Pepler GRM, Pepler PA (1976) Sedge Warbler migration and reed aphids. Br Birds 69:384–399

Biebach H (1995) Stopover of migrants flying across the Mediterranean Sea and the Sahara. Israel J Zool 41:387–392

Biebach H, Friedrich H, Heine G (1986) Interaction of bodymass, fat, foraging and stopover period in trans-Sahara migrating passerine birds. Oecologia 69:370–379

Biebach H, Friedrich H, Heine G, Jenni L, Jenni-Eiermann J, Schmidl H (1991) The daily pattern of autumn migration in the northern Sahara. Ibis 133:414–422

Biebach H, Biebach I, Friedrich W, Heine G, Partecke J, Schmidl D (2000) Strategies of passerine migration across the Mediterranean Sea and the Sahara Desert: a radar study. Ibis 142:623–634

Bruderer B (1994) Nocturnal bird migration in the Negev (Israel)—a tracking radar study. Ostrich 65:204–212

Carmi N, Pinshow B, Porter WP, Jaeger J (1992) Water and energy limitations on flight duration in small migrating birds. Auk 109:268–276

Delingat J, Bairlein F, Hedenström A (2008) Obligatory barrier crossing and adaptive fuel management in migratory birds: the case of the Atlantic crossing in northern wheatears (Oenanthe oenanthe). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 62:1069–1078

Hilgerloh G, Wiltschko W (2000) Autumn fat load and flight range of passerine long-distance migrants in southwestern Spain and northwestern Morocco. Ardeola 2:259–263

Hussel DJT, Lambert AB (1980) New estimates of weight loss in birds during nocturnal migration. Auk 97:547–558

Jenni L, Jenni-Eiermann S (1998) Fuel supply and metabolic constraints in migrating birds. J Avian Biol 29:521–528

Kaiser A (1993) A new multi-category classification of subcutaneous fat deposits of songbirds. J Field Ornithol 64:246–255

Kerlinger P, Moore FR (1989) Atmospheric structure and avian migration. In: Power DM (ed) Current ornithology. Plenum, New York, pp 109–142

Kvist A, Klaassen M, Lindström Å (1998) Energy expenditure in relation to flight speed: what is the power of mass loss rate estimates? J Avian Biol 29:485–498

Leger J, Larochelle J (2006) On the importance of radiative heat exchange during nocturnal flight in birds. J Exp Biol 209:103–114

Liechti F (2006) Birds: blowin by the wind. J Ornithol 147:202–211

Liechti F, Schmaljohann H (2007a) Wind-governed flight altitudes of nocturnal spring migrants over the Sahara. Ostrich 78:337–341

Liechti F, Schmaljohann H (2007b) Vogelzug über der westlichen Sahara. Ornithol Beob 104:33–44

Mead CJ (1972) Moreau’s paradox. BTO News 52:3

Meijer T, Möhring FJ, Trillmich FJ (1994) Annual and daily variation and body mass of starlings Sturnus vulgaris. J Avian Biol 25:98–104

Moreau RE (1961) Problems of Mediterranean–Saharan migration. Ibis 103a:373–427

Moreau RE (1972) The Palaearctic-African bird migration systems. Academic, London

Ottosson U, Rumsey S, Hjort C (2001) Migration of four Sylvia warblers through northern Senegal. Ringing Migr 20:344–351

Pearson DJ (1992) Northward passage of Palaearctic songbirds through Kenya. Proceedings of the Pan-African Ornithological Congress 7:113–124

Pilastro A, Spina F (1997) Ecological and morphological correlates of residual fat reserves in passerine migrants at their spring arrival in southern Europe. J Avian Biol 28:309–318

Salewski V, Schaub M (2007) Stopover duration of Palaearctic passerine migrants in the western Sahara—independent of fat stores? Ibis 149:223–236

Salewski V, Kéry M, Herremans M, Liechti F, Jenni L (2009) Estimating fat and protein fuel from fat and muscle scores in passerines. Ibis 151:640–653

Schmaljohann H, Liechti F, Bruderer B (2007a) Songbird migration across the Sahara: the non-stop hypothesis rejected! Proc R Soc Lond B 274:736–739

Schmaljohann H, Liechti F, Bruderer B (2007b) Daytime passerine migrants over the Sahara—are these diurnal migrants or prolonged flights of nocturnal migrants. Ostrich 78:357–362

Schmaljohann H, Bruderer B, Liechti F (2008) Sustained bird flights occur at temperatures far beyond expected limits. Anim Behav 76:1133–1138

Titov N (1999) Fat level and temporal pattern of diurnal movements of robins (Erithacus rubecula) at an autumn stopover site. Avian Ecol Behav 2:89–99

Wood B (1989) Comments of Bairlein’s hypothesis of trans-Saharan migration by short stages with stopovers. Ringing Migr 10:48–52

Acknowledgments

Mist-netting was only possible because of the help in the field of many volunteers, students, technicians and members of the Swiss Ornithological Institute, especially Alassan, F. Korner-Nievergelt, M. Liechti, V. Martignoli, A. Mauley and D. Zürrer whom we thank. Special thanks also to our indispensable local logistic team of Memoun, Mamadou, Bacar and Salem. The manuscript improved through discussion with B. Bruderer, L. Jenni and P. Jones. In Mauritania, invaluable assistance was given by the Ministry of Environment (MDRE), the Ministry of the Interior of Mauritania, the Centre for Locust Control (CLAA), German Technical Cooperation (GTZ), the Swiss Embassy in Algiers, the Swiss Honorary Consul and the German Embassy in Nouakchott. The Swiss Ornithological Institute’s project on Bird Migration across the Sahara was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Project No. 31-65349), the Foundations Volkhart, Vontobel, MAVA for Nature Protection, Ernst Göhner, Felis and Syngenta and also by BirdLife Switzerland, BirdLife International, the companies Bank Sarasin & Co., Helvetia Patria Insurances and F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG. Further partners are listed on http://www.vogelwarte.ch/sahara.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by H. Mouritsen.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Salewski, V., Schmaljohann, H. & Liechti, F. Spring passerine migrants stopping over in the Sahara are not fall-outs. J Ornithol 151, 371–378 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-009-0464-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-009-0464-5