Abstract

Avian malaria can affect survival and reproduction of their hosts. Two patterns commonly observed in birds are that females have a higher prevalence of malaria than do males and that prevalence decreases with age. The mechanisms behind these patterns remain unclear. However, most studies on blood parasite infections are based on cross-sectional analyses of prevalence, ignoring malaria related mortality and individual changes in infection. Here, we analyse both within-individual changes in malaria prevalence and long-term survival consequences of infection in the Seychelles Warbler (Acrocephalus sechellensis). Adults were less likely to be infected than juveniles but, contrary to broad patterns previously reported in birds, females were less likely to be infected than males. We show by screening individual birds in two subsequent years that the decline with age is a result both of individual suppression of infection and selective mortality. Birds that were infected early in life had a lower survival rate compared to uninfected birds, but among those that survived to be screened twice the proportion of infected birds had also decreased. Uninfected birds did not become infected later in life. Males were found to be more infected than females in this species possibly because, unlike most birds, males are the dispersing sex and the cost of dispersal may have to be traded against immunity. Infected males took longer to suppress their infection than did females. We conclude that these infections are indeed costly, and that age-related patterns in blood parasite prevalence are influenced both by suppression and selective mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Blood parasites are known to negatively influence the health of their hosts (Atkinson and Van Riper 1991; Ots and Horak 1998). This can have consequences for an individual’s fitness (Møller et al. 1990) through, for example, decreased reproductive output (Oppliger et al. 1996; Merino et al. 2000; Votypka et al. 2003), predation risk (Møller and Nielsen 2007) or survival (Sol et al. 2003; Stjernman et al. 2004).

Prevalence of blood parasites is a function of the transmission rate of the parasites by arthropod vectors and, consequently, of the abundance, host specificity and ecological requirements of the vectors (van Riper et al. 1986; Valkiunas 2005). Individual differences in parasite levels are believed to mainly arise through differences in exposure to vectors (Scheuerlein and Ricklefs 2004; but see Martinez-Abrain et al. 2004). An example of this is the restriction of Plasmodium in Hawaiian birds to elevations within the range of the introduced mosquito vector (van Riper et al. 1986). Differences between individuals within a population may also arise through variation in a range of characters influencing individual host susceptibility, e.g. previous health status (Sanz et al. 2002), reproductive effort (Norris et al. 1994; Merilä and Andersson 1999; Stjernman et al. 2004), or seasonal variation in hormonal levels (Deviche et al. 2001).

Two general findings in host–parasite assemblages are age- and sex-related differences in parasite prevalence. There is in general a higher prevalence of parasites in juvenile birds than in adults (Hudson and Dobson 1997; but see, e.g., Deviche et al. 2005). Three possible mechanisms have been proposed to explain this: higher exposure of juveniles to vectors, age-specific mortality of susceptible individuals due to heavy infestation, and development of acquired immunity (reviewed in Gregory et al. 1992). Since nestlings are thought to be particularly vulnerable to insect vectors when being immobile in the nest, birds are generally believed to acquire their first infections of blood parasites during their nestling period (but see Korpimaki et al. 1993), which may explain why juveniles are infected more than adults. This does not imply that adults may not be infected or reinfected, and a possible new appearance of parasites in the peripheral blood stream of a bird might therefore be caused by a relapse of a latent infection or due to a newly acquired infection. In feral pigeons (Columba livia) selection against heavily infected juveniles has been shown, but the difference in parasite prevalence between adults and juveniles could not be explained by selective mortality alone (Sol et al. 2000). Consequently, it is argued that this difference could also partly be explained by the development of the immune system (Sol et al. 2000). However, separating the effects of within- and between-individual variation on age-specific infection remains a major challenge. This is partly because it is difficult to detect the survival consequences of infections in natural, wild vertebrate populations. Studies are often not long lasting enough to obtain repeat measurements of known-age individuals across sufficient time, and wild individuals may be difficult to monitor adequately over their entire life-span. Therefore, most studies have been limited to comparing juveniles and adults, and have not followed juveniles into adulthood (Dawson and Bortolotti 1999; Deviche et al. 2001; Sol et al. 2003). Between-individual variation can thereby mask within-individual patterns in cross-sectional analyses (Nol and Smith 1987; Forslund and Part 1995). For example, juveniles with parasites will have lower survival compared to uninfected juveniles, which in cross-sectional analyses results in the observation that adults have lower parasite loads. To be able to separate within and between individual effects, a long-term study on a population in which individuals can be repeatedly screened for infection is required. The Seychelles Warbler (Acrocephalus sechellensis) population on Cousin Island (29 ha) in the Indian Ocean provides such as system.

In birds, sex-related differences in parasite prevalence may be caused by sex-specific life-histories resulting in differences in the trade-off between investment in immunity and other aspects of reproduction. Females should, for example, invest more in immunity than males, since they are expected to gain more fitness benefits through longevity, while males are expected to gain more by increasing mating success (Bateman’s principle for immunity; Rolff 2002). In contrast to the pattern seen for other types of parasites (McCurdy et al. 1998; Tschirren et al. 2003), females are normally infested more by blood parasites than are males, although several studies find the opposite effect (see references in McCurdy et al. 1998). Three possible causes for this female bias in blood parasitism have been proposed so far (McCurdy et al. 1998). First, the pattern may be due to differences in the immune system of the sexes (Grossman 1985; Schuurs and Verheul 1990). Both androgens in males and oestrogen in females may suppress or reallocate immune cell populations (Grossman 1985; Schuurs and Verheul 1990), but parasite prevalence may vary between sexes when the influence of oestrogen or testosterone is more pronounced. Second, differential exposure to vectors, e.g. through increased exposure of females to mosquitoes and flies during incubation (Korpimaki et al. 1993; Norris et al. 1994), may result in different rates of infection between the sexes. Since vectors are mainly dependent on smell and carbon dioxide to detect their hosts, females might be easier targets during periods of immobility on the nest. A third possible explanation is based on the different levels of stress imposed on the sexes by the mating systems. Individuals that invest more energy in reproduction are able to invest less in their immunity (Merilä and Andersson 1999). This may result in differences in parasite prevalence between the sexes (Sheldon and Verhulst 1996). In many bird species, females invest more in reproduction than do males (Trivers 1972); hence, females may be more likely to have blood parasites than males (e.g. Dawson and Bortolotti 2001). Experimental evidence is, however, lacking. Despite the many intensive studies on blood pathogens in birds, we still have only a limited understanding of the mechanisms behind sex dependent patterns of parasite prevalence.

In this study on the Cousin Island Seychelles Warblers, we analyse sex- and age-related differences in prevalence of infection by the haemosporidian parasite Haemoproteus sp. (hereafter referred to as avian malaria, but see Valkiunas et al. 2005) and investigate the consequences of infection for individual survival. We therefore combine parasite prevalence data with the long-term life-history dataset from this population. The Haemoproteus sp. is the only blood parasite that has been detected within Seychelles Warblers (Richardson DS and Hutchinsons K, unpublished data) and the vectors are probably ceratopogonid flies. Earlier work on Seychelles Warblers on Cousin has shown that, even though survival rates for juveniles and adults are high, there is a significantly lower survival probability for juveniles, even after controlling for confounding variables associated with survival (Brouwer et al. 2006). We might therefore expect that juveniles are influenced more by parasite infections compared to adults. As this island population experiences almost no emigration or immigration (immigration is 0.10%, n = 1,924; Komdeur et al. 2004), individual birds can be followed from birth to death. Hence, we have precise data on the status (breeding, helper or floater), age and presence of nearly all individuals in the population. Although dispersal patterns differ between the sexes (Komdeur 1996; Komdeur and Edelaar 2001; Eikenaar et al. 2008), resighting probabilities are close to one and estimated survival rates are thus not biased by undetected dispersal (Brouwer et al. 2006). This population therefore provides an excellent model system in which to assess the relative importance of selective mortality and suppression of infection and thereby investigate causes and consequences of avian malaria infections.

Methods

Study area and study population

The population of warblers on Cousin Island (4°19′S, 55°39′E) in The Seychelles has been monitored intensively from 1985 onwards. During the time of our study (1996–2005), almost all individuals were monitored throughout breeding attempts. Therefore, the reproductive history, age and survival data of up to 96% of all individual Seychelles Warblers are known throughout their lives (Richardson et al. 2004; for details, see Richardson et al. 2007). During each main breeding season (May–August), all territories were monitored for the presence of colour-ringed birds; consequently, survival of each bird can be determined accurately.

Birds were caught in mist nests and, if not caught previously, ringed with a unique combination of three colour rings and a numbered British Trust for Ornithology metal ring. A blood sample was taken from the brachial vein for molecular sexing analyses (Griffiths et al. 1998). A drop of blood was also used for a blood smear (see below). Breeding activity was determined by following territorial females continuously for 30 min, which is long enough to determine whether birds had begun nesting (Komdeur 1991). Activity was divided into four categories: non-breeding, nest building, incubation and nestling provisioning.

Blood smears and parasite analyses

Blood smears were collected in 1995, 1996 and 1997 from May until August from 50 individuals (27 males, 23 females). They were air-dried after collection and fixed by immersion in absolute methanol three times for 10 s. Smears were stained with hemacolor (Merck KGaA; Hauska et al. 1999) and screened under 1,000× magnification, and 300 fields (~6,000 erythrocytes) were screened for blood parasites (Ots and Horak 1998). All parasite scorings were conducted by the same person (K.v.O.) and without knowledge of the identity of the bird. Birds were designated as infested when at least one individual malaria parasite was found. It is well known that infections can persist at densities below the limit of detectability in blood smears (Atkinson and van Riper 1991). Intensity was not assayed because such counts are usually made relative to red or white blood cell density, both of which are themselves a function of parasite density (see, e.g., Norris et al. 1994). Thus, our measure of malaria prevalence was a simple presence or absence. On a subsample of the 50 individuals, from which we had multiple samples, we screened two blood smears that were collected 1 year apart (6 males, 14 females) to look at within-individual changes in parasite infection.

Territory quality

Seychelles Warblers are purely insectivorous and obtain 98% of their insect food from leaves (Komdeur 1991). The quality of a territory therefore depends on the amount of the insect prey available (with more insects in a high quality territory), reflecting the amount of foliage and territory size. Territory quality was determined monthly during the breeding season by measuring these variables and calculating territory quality following Komdeur (1994). Territories were divided into three categories according to the estimated number of leaf insects in a territory: low (0–1,500), medium (1,501–3,000) or high (>3,000). For this study, only blood smears of birds from high (n = 59) and low (n = 21) territories were available.

Statistical analyses

We used a binomial logistic regression with sex, territory quality (high versus low) and breeding status (breeding vs non-breeding) as fixed factors and age as covariate (actual age in years) to assess differences in parasite infection probability. As a measure of the condition of the bird, we used the weight of an individual corrected for its tarsus length by also including both variables as covariates in this model (Green 2001). We incorporated ‘individual’ as a random factor to control for multiple measurements. All variables and interactions were first included in the model (full model) and, using a backward-procedure, we removed the least significant term, starting with the interactions. This was repeated until only significant variables were present in the model (minimal adequate model). Because none of the two-way interactions were significant, these were omitted. To test within-individual changes in parasite infestation over age, we used a McNemar test for Significance of Changes (binomial distribution used). We used the software packages R 2.7.1 (R Development Core Team 2006) and SPSS 15.01 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) for the above-mentioned statistical analyses. All tests are two-tailed with α = 0.05.

Survival models

For the survival models, we used the data from birth of the individuals until and including 2005. Intensive effort was put into monitoring the small island population, thus we were able to achieve recapture rates of 1.0 for all years and groups in the dataset, i.e. no birds were observed after having been missed in a previous year (n = 50). This allowed us to reduce the number of parameters (because estimation of recapture rate was not necessary) which increased the power and precision in our statistical models. Survival was modelled using maximum-likelihood-based single-state open-population capture-recapture methods, as outlined by Lebreton et al. (1992) and implemented in the software M-Surge version 1.8.1 (Choquet et al. 2004). We analysed whether subsequent survival rate (φ) differed among birds diagnosed with or without malaria. We also considered if survival differed among year, sex or age, and if malaria had a similar effect on survival in these groups. Age consisted here of two classes: juveniles and adults. Seychelles Warblers are dependent on their parents for at least 3 months after leaving the nest and normally stay in their territory until they are 6 months of age (Komdeur 1996; Eikenaar et al. 2007). The minimum age of breeding is 8 months, but most birds do not breed until at least 1 year of age (Komdeur 1996). We therefore defined adult as birds older than 1 year, and juveniles as birds younger than 1 year. Birds were screened for malaria at different initial ages, and information about survival before the time of screening was excluded from the analysis so as not to bias upwards the survival estimates (because birds had, by definition, survived until being screened).

Various models, constrained in different ways, were compared by assessing how well they fit the data, with model selection being based on change in the AICc (Akaike’s Information Criterion, adjusted for small sample sizes; Burnham and Anderson 2002). We also present likelihood ratio tests for specific nested models where we wanted to test the effect of combining groups, calculated as the difference in deviance distributed as chi-square with degrees of freedom equal to the difference in number of parameters estimated.

Goodness-of-fit tests were performed using U-Care 2.2.5 (Choquet et al. 2005), and revealed that the Cormack-Jolly-Seber model (complete time-dependent survival and capture) fitted the data well (global test in U-Care, χ 2 = 0.71, df = 6, P = 0.99) and was therefore considered an appropriate umbrella model from which to start model selection. Comparison of models and parameter estimation was performed in M-Surge 1.8.1 (Choquet et al. 2004). Estimates are reported ± 1 SE.

Results

Factors associated with parasite prevalence

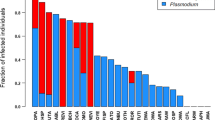

A total of 13 out of 50 birds (26%) were infected with Haemoproteus sp., the only avian blood parasite we found in our samples. Sex and age were significantly associated with parasite infection (Table 1). Males were more likely to be infected with Haemoproteus than were females, and parasite prevalence decreased over age for both sexes, although females in general were already free of parasites after 1 year, while males took at least 3 years to be free of parasites (Fig. 1, Table 1). Breeding status, territory quality and condition were not significantly associated with parasite prevalence (Table 1).

Proportion of Seychelles Warblers (Acrocephalus sechellensis) infected with avian malaria (±SE). Means for females (closed bars) and males (open bars) of three age classes are shown. N Sample size. The data were analyzed with age as a continuous variable (Table 1), but for reasons of clarity the age is split up into three age classes (0–1 years, 2–3 years, or older than 3 years)

We compared parasite prevalence of the 20 individuals caught and screened for parasites twice in two subsequent years (1996 and 1997). Of these, six birds (30%) were infected in the first screening and only one of these also in the second screening 1 year later (5%), indicating that a decrease in parasite prevalence occurs over age (McNemar Test; n = 20, exact sign. P = 0.03; Fig. 2). None of the initially uninfected birds were infected at the second screening.

Parasite related survival

Overall, birds diagnosed with a blood parasite infection tended to have lower survival compared to birds diagnosed as being uninfected, but the effect was not statistically significant [n = 13 (infected) vs 37 (uninfected), φ = 0.79 ± 0.06 vs 0.86 ± 0.02, χ 2 = 1.7, df = 1, P = 0.19). However, the group of birds diagnosed with malaria as juveniles (n = 9) experienced significantly lower survival rates than other birds sampled (juveniles without malaria and all adults, n = 41; Fig. 3, φ = 0.71 ± 0.08 vs 0.86 ± 0.02, χ 2 = 4.1, P = 0.04). There was no effect of malaria on survival among birds screened when adult (n = 4 vs. 25, φ = 0.88 ± 0.07 vs 0.86 ± 0.03, χ 2 = 0.1, df = 1, P = 0.8) or when juvenile (n = 9 vs 12, φ = 0.71 ± 0.08 vs 0.85 ± 0.05, χ 2 = 2.3, df = 1, P = 0.13). There was also no overall difference in survival between juveniles with malaria and those screened as adults with malaria (n = 21 vs 29, φ = 0.8 ± 0.04 vs 0.89 ± 0.03, χ 2 = 1.9, df = 1, P = 0.17). Models including a term for sex were always less favoured by AIC than models without such effects, indicating that parasite related survival did not differ between the sexes. We do not, therefore, report results from models including a sex effect.

There was a clear difference in survival among years (compared to constant survival: χ 2 = 26.7, df = 9, P = 0.002), and taking this temporal effect into account strengthened the patterns of survival reported above. The best model (Table 2a) was one which included survival differing among years, with an additive effect of being diagnosed with malaria as juvenile (compared to year effect alone: χ 2 = 8.4, df = 1, P = 0.004). Similarly, among birds screened when juvenile there was a significant effect of including malaria infection as a factor in addition to the year effect (χ 2 = 4.2, df = 1, P = 0.04; Table 2b). We found no such effect among birds screened when adult (χ 2 = 0.1, df = 1, P = 0.7; Table 2c), but the number of available infected adults involved was low.

Discussion

We found that Seychelles Warblers exhibit sex- and age-related differences in parasite prevalence. Males were more likely to be infected with Haemoproteus sp. compared to females, which confirms patterns in other birds, and the probability of being infected decreased with age in both sexes. We found that this age-related difference in malaria infection also occurs within individuals. Most importantly, we have shown that parasite infection at an early age is associated with lower survival.

The effect of early infection on survival was to some extent masked by strong temporal effects on survival; only when we accounted for among-year variation in survival did it become clear that survival is associated with malaria infection in juveniles. In domestic birds, haematozoan-induced mortality is common; most studies on wild birds, however, have not found effects on survival (see references in Marzal et al. 2008).

The decline in parasite prevalence over age in Seychelles Warblers is in agreement with previous findings in birds (Hudson and Dobson 1997; Sol et al. 2003). Our data on within-individual prevalence are consistent with an elevated immune defense later in life, since birds might have been able to rid themselves of blood parasites, or at least suppress their abundance below a detectable level, and none of the non-infected birds became infected later in life. However, selective mortality also contributed to the age-dependent levels of infection observed in the Seychelles Warbler. Individuals infected as juveniles had lower survival rates compared to all other individuals including uninfected juveniles and both infected and uninfected adults.

These results suggest that the negative effects of having been infected by blood parasites are most pronounced early in life; individuals are usually infected early in life and those that are not able to suppress the infection as juveniles are more likely to die before reaching adulthood. Immune systems of young birds may not be developed completely since a major part of the immunity is acquired. Infection might therefore be disproportionately costly for juveniles (e.g. Van Oers et al. 2002). So, even though adults are constantly facing new infections, infections early in life seem to have the highest impact on survival. However, since we have based our results on the visual screening of blood smears only, we cannot rule out infections that were not detected through this method. Studies combining blood-smear counts with PCR based screening methods of detecting infection in blood (Fallon et al. 2003; Hellgren et al. 2004) may provide greater resolution, although even PCR methods will miss infections that are no longer circulating in the peripheral blood stream (Valkiunas et al. 2005).

In contrast to McCurdy et al. (1998), where females had higher infection rates than males, we found that in the Seychelles Warbler more infections were established in males than in females. Sex differences in parasite prevalence may be caused by many different factors. One possibility is differential exposure of the sexes to vectors. In the Seychelles Warbler, individuals are most likely infected as nestlings; indeed, none of the non-infected juveniles we screened became infected later in life. As there is no reason why vectors will have a preference for individuals of either sex during the nestling stage, differential exposure to vectors seems an unlikely explanation for the sex differences found. Male Seychelles Warblers typically disperse from their territory of birth and females stay in their territory (Komdeur 2003). Therefore, an alternative explanation for the higher levels of infection in males might be that costs of dispersal are traded against costs of immunity in males. Since dispersal is expected to be more costly then staying in the home territory, males may be able to invest less in immunity because of the cost of dispersal. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that females in general were already free of parasites after 1 year, while males took at least 3 years to be free of parasites (Fig. 1). These time periods mirror the typical ages at which the sexes settle in a territory (Komdeur 1991). This is also in agreement with Bateman’s principle of immunity, where females are expected to invest more in longevity than are males (Rolff 2002). In the Seychelles Warbler, females are more prone to wait for a suitable breeding possibility in the home territory and males are more prone to leave the territory. This might come at a cost when males get exposed to additional vectors during the dispersal phase. Nevertheless, the small sample sizes do not allow strong conclusions and experimental evidence is needed to test this properly. For example, males and females could be experimentally freed of infections and subsequently reinfected again to reveal the causal relationship between dispersal and blood parasite prevalence.

In this study, we have documented sex- and age-related differences in Haemoproteus prevalence. Using repeated screening of individuals, we were able to show that individuals can suppress their infections and that this may partly explain the decrease in prevalence with age. However, since juveniles with infection have lower survival than other birds, there were also fitness costs involved with being parasitized. Males seem to be forced to pay the costs associated with dispersal since breeding opportunities in their natal territories are low (Richardson et al. 2002). These costs may include reduced investment in immunity compared to females. Detailed studies screening large samples of individuals repeatedly, combined with experimental medication and re-infection, are now needed to further disentangle causes and consequences of parasite infections.

Zusammenfassung

Verringerte Prävalenz von Blutparasiten mit zunehmendem Alter beim Seychellenrohrsänger: Selektive Mortalität oder Unterdrückung einer Infektion?

Vogelmalaria kann das Überleben und die Fortpflanzung der Wirte beeinflussen. Zwei Muster, die oftmals bei Vögeln beobachtet werden, sind, dass Weibchen eine höhere Prävalenz von Malaria haben als Männchen und dass die Prävalenz mit zunehmendem Alter abnimmt. Die Mechanismen hinter diesen Mustern sind unklar. Die meisten Studien über die Infektionen mit Blutparasiten basieren jedoch auf Querschnittsanalysen von Prävalenz und ignorieren malariabedingte Mortalität und individuelle Veränderungen in der Infektion. Hier analysieren wir sowohl Veränderungen in der Malaria-Prävalenz in Individuen als auch die Langzeitfolgen einer Infektion für das Überleben bei Seychellenrohrsängern (Acrocephalus sechellensis). Erwachsene Tiere waren mit geringerer Wahrscheinlichkeit infiziert als Jungtiere, doch im Gegensatz zu zuvor bei anderen Vögeln festgestellten Mustern waren Weibchen mit geringerer Wahrscheinlichkeit infiziert als Männchen. Durch das Testen einzelner Vögel in zwei aufeinanderfolgenden Jahren zeigen wir, dass der Abfall mit zunehmendem Alter sowohl auf eine individuelle Unterdrückung der Infektion als auch auf selektive Mortalität zurückzuführen ist. Vögel, die im frühen Alter infiziert wurden, wiesen verglichen mit uninfizierten Vögeln eine niedrigere Überlebensrate auf, aber unter den Tieren, die bis zum zweiten Test überlebten, hatte der Anteil infizierter Vögel ebenfalls abgenommen. Nicht infizierte Vögel wurden auch später im Leben nicht infiziert. Wir fanden, dass bei dieser Art Männchen häufiger infiziert waren als Weibchen, möglicherweise da, anders als bei anderen Arten, Männchen hier das abwandernde Geschlecht sind und es sein könnte, dass die Kosten der Abwanderung gegen die Immunität abgewogen werden müssen. Infizierte Männchen brauchten länger als Weibchen, um ihre Infektion zu unterdrücken. Wir schlussfolgern, dass diese Infektionen in der Tat mit Kosten verbunden sind und dass altersbedingte Muster in der Blutparasiten-Prävalenz sowohl durch Unterdrückung der Infektion als auch durch selektive Mortalität beeinflusst werden.

Change history

29 October 2009

An Erratum to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-009-0465-4

References

Atkinson CT, Van Riper C (1991) Pathogenicity and epizootiology of avian hematozoa: Plasmodium, Leucocytozoon and Haemoproteus. In: Loye J, Zuk M (eds) Bird-parasite interactions. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 19–49

Brouwer L, Richardson DS, Eikenaar C, Komdeur J (2006) The role of group size and environmental factors on survival in a cooperatively breeding tropical passerine. J Anim Ecol 75:1321–1329

Burnham KP, Anderson DR (2002) Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. Springer, New York

Choquet R, Reboulet AM, Pradel R, Gimenez O, Lebreton JD (2004) M-SURGE: new software specifically designed for multistate capture-recapture models. Anim Biodivers Conserv 27:207–215

Choquet R, Reboulet A M, Lebreton J D, Gimenez O, Pradel R (2005) U-CARE 2.2 User’s Manual

Dawson RD, Bortolotti GR (1999) Prevalence and intensity of hematozoan infections in a population of American kestrels. Can J Zool 77:162–170

Dawson RD, Bortolotti GR (2001) Sex-specific associations between reproductive output and hematozoan parasites of American kestrels. Oecologia 126:193–200

Deviche P, Greiner EC, Manteca X (2001) Seasonal and age-related changes in blood parasite prevalence in Dark-eyed Juncos (Junco hyemalis, Aves, Passeriformes). J Exp Zool 289:456–466

Deviche P, McGraw K, Greiner EC (2005) Interspecific differences in hematozoan infection in Sonoran desert Aimophila sparrows. J Wildl Dis 41:532–541

Eikenaar C, Richardson DS, Brouwer L, Komdeur J (2007) Parent presence, delayed dispersal, and territory acquisition in the Seychelles warbler. Behav Ecol 18:874–879

Eikenaar C, Richardson DS, Brouwer L, Komdeur J (2008) Sex biased natal dispersal in a closed, saturated population of Seychelles warblers Acrocephalus sechellensis. J Avian Biol 39:73–80

Fallon SM, Ricklefs RE, Swanson BL, Bermingham E (2003) Detecting avian malaria: an improved polymerase chain reaction diagnostic. J Parasitol 89:1044–1047

Forslund P, Part T (1995) Age and reproduction in birds––hypotheses and tests. Trends Ecol Evol 10:374–378

Green AJ (2001) Mass/length residuals: measures of body condition or generators of spurious results? Ecology 82:1473–1483

Gregory RD, Montgomery SSJ, Montgomery WI (1992) Population biology of Heligmosomoides polygyros (Nematoda) in the wood mouse. J Anim Ecol 61:749–757

Griffiths R, Double MC, Orr K, Dawson JG (1998) A DNA test to sex most birds. Mol Ecol 7:1071–1075

Grossman CJ (1985) Interactions between the gonadal-steroids and the immune system. Science 227:257–261

Hauska H, Scope A, Vasicek L, Reauz B (1999) Comparison of different staining methods for avian blood cells. Tierarztl Prax 27:280–287

Hellgren O, Waldenstrom J, Bensch S (2004) A new PCR assay for simultaneous studies of Leucocytozoon, Plasmodium, and Haemoproteus from avian blood. J Parasitol 90:797–802

Hudson PJ, Dobson AP (1997) Host-parasite processes and demographic consequences. In: Clayton DH, Moore J (eds) Host-parasite evolution: general principles and avian models. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 128–154

Komdeur J (1991) Cooperative breeding in the Seychelles Warbler. PhD thesis, University of Cambridge, Cambridge

Komdeur J (1994) Experimental evidence for helping and hindering by previous offspring in the cooperative breeding seychelles warbler Acrocephalus sechellensis. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 34:175–186

Komdeur J (1996) Facultative sex ratio bias in the offspring of Seychelles warblers. Proc R Soc Lond B 263:661–666

Komdeur J (2003) Daughters on request: about helpers and egg sexes in the Seychelles warbler. Proc R Soc Lond B 270:3–11

Komdeur J, Edelaar P (2001) Male Seychelles warblers use territory budding to maximize lifetime fitness in a saturated environment. Behav Ecol 12:706–715

Komdeur J, Piersma T, Kraaijeveld K, Kraaijeveld-Smit F, Richardson DS (2004) Why Seychelles Warblers fail to recolonize nearby islands: unwilling or unable to fly there? Ibis 146:298–302

Korpimaki E, Hakkarainen H, Bennett GF (1993) Blood parasites and reproductive success of tengmalm owls––detrimental effects on females but not on males. Funct Ecol 7:420–426

Lebreton JD, Burnham KP, Clobert J, Anderson DR (1992) Modeling survival and testing biological hypotheses using marked animals––a unified approach with case-studies. Ecol Monogr 62:67–118

Martinez-Abrain A, Esparza B, Oro D (2004) Lack of blood parasites in bird species: does absence of blood parasite vectors explain it all? Ardeola 51:225–232

Marzal A, Bensch S, Reviriego M, Balbontin J, De Lope F (2008) Effects of malaria double infection in birds: one plus one is not two. J Evol Biol 21:979–987

McCurdy DG, Shutler D, Mullie A, Forbes MR (1998) Sex-biased parasitism of avian hosts: relations to blood parasite taxon and mating system. Oikos 82:303–312

Merilä J, Andersson M (1999) Reproductive effort and success are related to haematozoan infections in blue tits. Ecoscience 6:421–428

Merino S, Moreno J, Sanz JJ, Arriero E (2000) Are avian blood parasites pathogenic in the wild? A medication experiment in blue tits (Parus caeruleus). Proc R Soc Lond B 267:2507–2510

Møller AP, Nielsen JT (2007) Malaria and risk of predation: a comparative study of birds. Ecology 88:871–881

Møller AP, Allander K, Dufva R (1990) Fitness effects of parasites on passerine birds: a review. In: Blondel J, Gosler AG, Lebreton JD, McCleery RH (eds) Population biology of passerine birds. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 269–280

Nol E, Smith JNM (1987) Effects of age and greeding experience on seasonal reproductive success in the song sparrow. J Anim Ecol 56:301–313

Norris K, Anwar M, Read AF (1994) Reproductive effort influences the prevalence of haematozoan parasites in great tits. J Anim Ecol 63:601–610

Oppliger A, Christe P, Richner H (1996) Clutch size and malaria resistance. Nature 381:565

Ots I, Horak P (1998) Health impact of blood parasites in breeding great tits. Oecologia 116:441–448

R Development Core Team (2006) R Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org

Richardson DS, Burke T, Komdeur J (2002) Direct benefits and the evolution of female-biased cooperative breeding in Seychelles warblers. Evol Int J org Evol 56:2313–2321

Richardson DS, Komdeur J, Burke T (2004) Inbreeding in the seychelles warbler: environment-dependent maternal effects. Evol Int J org Evol 58:2037–2048

Richardson DS, Burke T, Komdeur J (2007) Grandparent helpers: the adaptive significance of older, postdominant helpers in the Seychelles warbler. Evol Int J org Evol 61:2790–2800

Rolff J (2002) Bateman’s principle and immunity. Proc R Soc Lond B 269:867–872

Sanz JJ, Moreno J, Arriero E, Merino S (2002) Reproductive effort and blood parasites of breeding pied flycatchers: the need to control for interannual variation and initial health state. Oikos 96:299–306

Scheuerlein A, Ricklefs RE (2004) Prevalence of blood parasites in European passeriform birds. Proc R Soc Lond B 271:1363–1370

Schuurs AHWM, Verheul HAM (1990) Effects of gender and sex steroids on the immune-response. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 35:157–172

Sheldon BC, Verhulst S (1996) Ecological immunology: costly parasite defences and trade-offs in evolutionary ecology. Trends Ecol Evol 11:317–321

Sol D, Jovani R, Torres J (2000) Geographical variation in blood parasites in feral pigeons: the role of vectors. Ecography 23:307–314

Sol D, Jovani R, Torres J (2003) Parasite mediated mortality and host immune response explain age-related differences in blood parasitism in birds. Oecologia 135:542–547

Stjernman M, Raberg L, Nilsson JA (2004) Survival costs of reproduction in the blue tit (Parus caeruleus): a role for blood parasites? Proc R Soc Lond B 271:2387–2394

Trivers RL (1972) Parental investment and sexual selection. In: Campbell B (ed) Sexual selection and the descent of man, 1871–1971. Aldine, Chicago, pp 136–179

Tschirren B, Fitze PS, Richner H (2003) Sexual dimorphism in susceptibility to parasites and cell-mediated immunity in great tit nestlings. J Anim Ecol 72:839–845

Valkiunas G (2005) Avian malaria parasites and other haemosporidia. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida

Valkiunas G, Anwar AM, Atkinson CT, Greiner EC, Paperna I, Peirce MA (2005) What distinguishes malaria parasites from other pigmented haemosporidians? Trends Parasitol 21:357–358

Van Oers K, Heg D, Quenec’hdu SLD (2002) Anthelminthic treatment negatively affects chick survival in the Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus. Ibis 144:509–517

van Riper C, van Riper SG, Goff M, Laird M (1986) The epizootiology and ecological significance of malaria in Hawaiian land birds. Ecol Monogr 56:327–344

Votypka J, Simek J, Tryjanowski P (2003) Blood parasites, reproduction and sexual selection in the red-backed shrike (Lanius collurio). Ann Zool Fenn 40:431–439

Acknowledgments

Nature Seychelles kindly allowed us to work on Cousin Island and provided accommodation and facilities during our stay. The Department of Environment and the Seychelles Bureau of Standards gave permission for fieldwork and sampling. We thank Karen Blaakmeer for her important help with data collection and Gerry Dorrestein (University of Utrecht) for his help in parasite identification. This work was supported by grants from the UK Natural Environmental Research Council (to JK) and the Australian Research Council (to J.K. and K.v.O.). K.v.O. is supported by NWO (VENI grant 863.05.013), D.S.R. was supported by a NERC postdoctoral fellowship.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by C. G. Guglielmo.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

van Oers, K., Richardson, D.S., Sæther, S.A. et al. Reduced blood parasite prevalence with age in the Seychelles Warbler: selective mortality or suppression of infection?. J Ornithol 151, 69–77 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-009-0427-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-009-0427-x