Abstract

This paper examines the impact of trade policy on specialization patterns in ten Latin American countries over the period 1985–1998. These countries are natural case studies because in the last decades they implemented comprehensive trade liberalization programs, both generally and preferentially, starting from relatively high tariff protection levels. Our econometric results suggest that reducing own most favored nation tariffs is associated with increasing manufacturing production specialization. Furthermore, we find that preferential trade liberalization and differences in the degree of unilateral openness have resulted in increased dissimilarities in manufacturing production structures across countries. These results are robust across specialization measures and estimation methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Unfortunately, Paraguay could not be included in this study because sectoral production data for this country are missing.

The group of countries we consider is relatively homogenous in terms of their capital-labor ratio when compared to developed countries and other developing countries, so that intra-sectoral heterogeneity across economies is less an issue in our analysis.

A sufficient condition is that there are at least as many factors as goods (Redding 2002).

The translog model is frequently interpreted as a second-order approximation to an unknown functional form (Greene 1997).

The logarithm of H is interpreted as a function of the logarithm of the underlying variables.

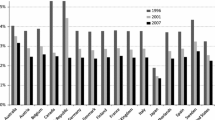

It should be stressed that, except for Mexico and Venezuela, Latin American countries’ simple average tariffs are very close to the theoretically consistent trade restrictiveness indexes calculated by Kee et al. (2004). The same holds for the trade-weighted average tariffs and the so-called mercantilist index of trade policy as estimated by Anderson and Neary (2003).

We have estimated Eq. (15) expanded with the variable in question using the generalized method of moments (GMM) procedure proposed by Blundell and Bond (1998). This variable turns out to be non-significant, whereas remaining estimated coefficients do not significantly differ from those reported below. These estimation results are available from the authors upon request.

Rebelo and Vegh (1995) maintain that exchange rate-based stabilizations have tended to be associated with real exchange rate appreciations and sharp deterioration of external accounts reflecting a large increase of durables and capital goods imports.

The estimated rho parameter is around 0.400. The estimated coefficient on the lagged dependent variable according to the bias-corrected LSDV estimator developed by Kiviet (1995) is around 0.600. Further, we find that this coefficient is almost identical when estimating pure autoregressive models using both the Arellano and Bond (1991) and Blundell and Bond (1998) estimators (0.373 and 0.400, respectively).

We have tested for non-stationarity to determine whether there are concrete reasons to be concerned about this issue. In particular, we have performed the Levin–Lin–Chu test (Levin et al. 2002) for panel unit roots on the specialization variable for alternative balanced panels. In doing this, we have introduced one lag of this variable to allow for serial correlation in the errors. The null hypothesis of unit root is strongly rejected for all considered configurations, regardless whether we include a time trend or not.

Estimation results with tariff variables lagged one period to account for the possibility that their impact on specialization patterns follow with a lag are essentially the same. These results are available from the authors upon request.

Similar results have been obtained using the average preferential tariffs set in the context of the LAIA. These results are available from the authors upon request.

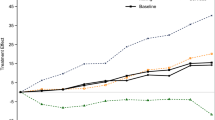

Figure 3 shows that levels of specialization and their evolution over time differ across economies. To exclude the possibility that these findings are driven by specific country experiences, we drop one country at a time from the sample and re-estimate Eq. (12). Regression results basically coincide with those shown in Table 1 thus confirming the main messages. We also explore whether estimates are sensitive to changes in the sample period, by successively considering periods beginning in 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989, and 1990. Again, results are essentially the same. These results are not reported, but are available from the authors upon request.

Following a suggestion of a referee, we have also performed fixed effects instrumental variables estimation. Main results from this exercise do not significantly differ from those reported here. These results are available from the authors upon request.

There is an additional, more complicated issue in this analysis, namely, if specialization, tariffs, and the level of development are jointly determined, there will be both direct and indirect effects that should be disentangled. For example, real exchange rate misalignments may have direct effects on specialization as well as indirect effects through the influence that they likely exert on choosing the level of tariff protection. We have therefore estimated alternative specifications of systems of equations by 3SLS and GMM where these variables are simultaneously treated as endogenous. This multiple equation strategy generates similar results to those from the single equation one. In addition, we observe that less diversified economies indeed set lower tariffs and tend to have lower levels of GDP per capita. These results are not reported but are available from the authors upon request.

We have tested for non-stationarity of the specialization measure also in this case. The Levin–Lin–Chu test (Levin et al. 2002) for panel unit roots suggests that series are stationary. This holds regardless whether we include a time trend or not and the specific balanced panel being considered.

Bolivia suffered from a severe macroeconomic crisis including a hyperinflation episode over the first part of the 1980 s.

The negative estimated coefficient on DIFF REERM may reflect the fact that, after controlling for bilateral preferential tariffs and differences in extra-regional tariffs and levels of development, differences in real exchange rates for imports have acted to compensate differences in overall levels of manufacturing competitiveness thereby contributing to reduce disparities in industrial structures.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Zilibotti, F. (1997). Was promotheus unbound by change? Risk, diversification, and growth. Journal of Political Economy, 105(4), 709–751.

Anderson, J., & Neary, P. (2003). The mercantilist index of trade policy. International Economic Review, 44(2), 627–649.

Anderson, J., & van Wincoop, E. (2004). Trade costs. Journal of Economic Literature, 42(3), 691–751.

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297.

Balassa, B., & Noland, M. (1989). The changing comparative advantage of Japan and the United States. Journal of the Japanese and International Economics, 3(2), 174–188.

Baldwin, R., Forslid, R., Martin, P., Ottaviano, G., & Robert-Nicoud, F. (2003). Economic geography and public policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Baltagi, B. (1995). Econometric analysis of panel data. Chichester: Wiley.

Beck, N., & Katz, J. (1996). Nuissance vs. substance: Specifying and estimating time-series-cross-section models. Political Analysis, 6(1), 1–36.

Bensidoun, I., Gaulier, G., & Ünal-Kesenci, D. (2001). The Nature of specialization matters for growth: An empirical investigation. (CEPII Document de Travail 13). Centre d’Etudes Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales, Paris.

Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143.

Bond, S. (2002). Dynamic panel data models: A guide to microdata methods and practice. Portuguese Economic Journal, 1(2), 141–162.

Brülhart, M. (2001). Evolving geographical specialisation of European manufacturing industries. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv/Review of World Economics, 137(2), 215–243.

Combes, P., & Overman, H. (2004). The spatial distribution of economic activities in the European Union. In V. Henderson & J. Thisse (Eds.), Handbook of regional and urban economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Cowell, F. (2000). Measuring inequality. In F. Bourguignon & A. Atkinson (Eds.), Handbook of income distribution. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Dixit, A., & Norman, V. (1980). The theory of international trade. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dornbusch, R., Fischer, S., & Samuelson, P. (1977). Comparative advantages, trade, and payments in a Ricardian model with a continuum of goods. American Economic Review, 67(5), 823–839.

Edwards, S. (1994). Macroeconomic stabilization in Latin America: Recent experience and some sequencing issues. (NBER Working Paper 4697). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Eichengreen, B. (1992). Should the Maastricht treaty be saved? (Princeton Studies in International Finance 74). Princeton University: International Finance Section.

Eichengreen, B. (1993). European monetary unification. Journal of Economic Literature, 31(3), 1321–1357.

Fernández-Arias, E., Panizza, U., & Stein, E. (2002). Trade agreements, exchange rate disagreements. Washington: Inter-American Development Bank.

Frankel, J., & Rose, A. (1998). The endogeneity of the optimum currency area criteria. Economic Journal, 108(449), 1009–1025.

Fujita, M., Krugman, P., & Venables, A. (1999). The spatial economy: Cities, regions and international trade. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Godlfajn, I., & Valdes, R. (1999). The aftermath of appreciations. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(1), 229–262.

Greene, W. (1997). Econometric analysis. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Haaland, J., Kind, H., Midelfart-Knarvik, K., & Torstensson, J. (1999). What determines the economic geography of Europe? (CEPR Discussion Paper 2072). London: Center for Economic Policy Research.

Hall, R., & Jones, C. (1999). Why do some countries produce so much more output per worker than others? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(1), 83–116.

Harrigan, J. (1997). Technology, factor supplies, and international specialization: Estimating the neoclassical model. American Economic Review, 87(4), 475–494.

Helpman, E. (1987). Imperfect competition and international trade: Evidence from fourteen industrialised countries. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 1(1), 62–81.

Hodrick, R., & Prescott, E. (1997). Postwar U.S. business cycles: An empirical investigation. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 29(1), 1–16.

Imbs, J., & Wacziarg, R. (2003). Stages of diversification. American Economic Review, 93(1), 63–86.

Kee, H., Nicita, A., & Olarreaga, M. (2004). Import demand elasticities and trade distortions. (CEPR Discussion Paper 4669). London: Center for Economic Policy Research.

Kenen, P. (1969). The theory of optimum currency area: An eclectic view. In R. Mundell & A. Swoboda (Eds.), Monetary problems of the international economy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kiviet, J. (1995). On bias, inconsistency, and efficiency of various estimators in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 53–78.

Kohli, U. (1991). Technology, duality, and foreign trade. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Krugman, P. (1993). Lessons of Massachusetts for EMU. In F. Giavazzi & F. Torres (Eds.), The transition to economic and monetary union in Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Levin, A., Lin, C., & Chu, C. (2002). Unit root tests in panel data: Asymptotic and finite-sample properties. Journal of Econometrics, 108(1), 1–24.

Lucas, R. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(1), 3–42.

Midelfart-Knarvik, K., Overman, H., Redding, S., & Venables, A. (2000). The location of European industry. (Economic Papers 142). Brussels: European Commission.

Obstfeld, M., & Rogoff, K. (1996). Foundations of international macroeconomics. Cambidge, MA: MIT Press.

Perry, G., de Ferranti, D., Lederman, D., & Maloney, W. (2001). From the natural resources to the knowledge economy: Trade and job quality. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Quah, D., & Rauch, J. (1990). Openness and the rate of economic growth. Mimeo: UCSD.

Rebelo, S., & Vegh, C. (1995). Real effects of exchange rate-based stabilization: An analysis of competing theories. In B. Bernanke & J. Rotemberg (Eds.), NBER macroeconomic annual 1995. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Redding, S. (1999). Dynamic comparative advantage and the welfare effects of trade. Oxford Economic Papers, 51(1), 15–39.

Redding, S. (2002). Specialization dynamics. Journal of International Economics, 58(2), 299–334.

Ricci, L. (2006). Uncertainty, flexible exchange rates, and agglomeration. Open Economies Review, 17(2), 197–219.

Romalis, J. (2004). Factor proportions and the structure of commodity trade. American Economic Review, 94(1), 67–97.

Sapir, A. (1996). The effects of Europe’s internal market program on production and trade: A first assessment. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv/Review of World Economics, 132(3), 457–475.

Terra, C., & Valladares, F. (2003). Real exchange rate misalignments. (Ensaios Economicos 493). Rio de Janeiro: FGV.

Venables, A. (2003). Winners and losers from regional integration agreements. Economic Journal, 113(490), 747–761.

Weinhold, D., & Rauch, J. (1999). Openness, specialization, and productivity growth in less developed countries. The Canadian Journal of Economics, 32(4), 1009–1027.

Woodland, A. (1982). International trade and resources allocation. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Cristina Terra who kindly provided us with series of exchange rate misalignments. We also thank the editor, a referee, Giorgio Barba Navaretti, Robin Burgess, Joseph Francois, Sandra Poncet, Beata Smarzynska Javorcik, Julia Woertz, and participants at the 20th Congress of the European Economics Association (Amsterdam) and the third Workshop of the CEPR RTN “Trade, Industrialization, and Development” (Chianti) for helpful comments and suggestions. The views and interpretation in this document are strictly those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Inter-American Development Bank, its Executive Directors, or its member countries. Other usual disclaimers also apply.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

About this article

Cite this article

Volpe Martincus, C., Estevadeordal, A. Trade policy and specialization in developing countries. Rev World Econ 145, 251–275 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-009-0014-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-009-0014-5