Abstract

We studied the social behaviors of western Assamese macaques (Macaca assamensis pelops) at Shivapuri Nagarjun National Park, Nepal from 2014 to 2017 and of eastern Assamese macaques (M. a. assamensis) at Wat Tham Pla, Thailand from 2008 to 2012. The behaviors of both subspecies of M. assamensis were compared to those of Tibetan macaques (M. thibetana) at Huangshan, China from 1989 to 1993. The study groups were free-ranging, provisioned daily, and habituated to observers. We observed adult males and adult females for 10 h each during both the birth and mating seasons using focal-animal sampling as well as all-occurrence-behavior sampling. All three species of macaque formed multi-male multi-female social groups with female philopatry, male dispersal, and a linear dominance hierarchy among adult females. Additionally, although they did not make genital–genital or oral–oral contact, all three species performed various affiliative behaviors with genital touching and genital showing during not only the mating season but also the birth season. However, we found more differences in the repertoire of social behaviors between western and eastern Assamese macaques than between eastern Assamese and Tibetan macaques. Bridging behavior, in which two adults simultaneously lift up an infant, was recorded in Tibetan and eastern Assamese macaques. Males of these two macaques sucked the infant’s genitalia during bridging behavior and dyadic male–infant interactions, whereas this behavior was not observed in western Assamese macaques. In addition, only male Tibetan macaques directly sucked the penis of another male, although males of all three macaque species inspected female genitalia and the genital inspection was occasionally accompanied by oral–genital contact. These results indicate that bridging behavior and the sucking of an infant’s genitalia by adult males evolved in a sinica species-group of the genus Macaca, particularly in the clade of Tibetan and eastern Assamese macaques, and that penis sucking between adult males occurred last in Tibetan macaques. Digital video images related to this article are available at http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430ma09a, http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430mt06a, http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430mt01a, http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430ma01a, http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430ma10a, http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430ma04a, and http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430ma07a.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The genetic and morphological traits of focal species provide important evidence for understanding the evolutionary processes in and the phylogenetic relationships of primates and other animals. Additionally, information regarding inter-species differences in social behaviors, patterns of social interactions, and social relationships is also crucial, as social relationships in non-human primates are strongly affected by both ecological and phylogenetic factors (Balasubramaniam et al. 2018). Based on the behavioral repertories of each species, we may be able to reconstruct the social relationships and social structure of the common ancestor (Mori 1983).

Studies of various species in the genus Macaca, Cercopithecidae, Primates, have revealed that all macaques share the common features of forming a multi-male multi-female social group with female philopatry, male dispersal, and a linear dominance hierarchy (Thierry et al. 2004). However, variations exist in their “dominance style” and the degree of kin-biased social relationships between females (Berman and Thierry 2010; de Waal and Luttrell 1989). Recent studies have systematically examined the variations in social relationships between females (Balasubramaniam et al. 2012). In addition to differences in social relationships between females, many inter-species differences occur in the social relationships between males and also between males and females. Compared to females, however, fewer comparative studies have examined the social interactions between males and between males and females. For example, genital touching and oral–genital contact have been reported in Tibetan (Macaca thibetana) (Ogawa 1995, 2006) and stumptail macaques (M. arctoides) (Estrada and Sandoval 1977), but these behaviors have not been reported for most other macaque species. Similarly, frequent triadic male–infant interactions have been reported only in Barbary (M. sylvanus) (Deag and Crook 1971), Tibetan (Ogawa 1995, 2006), and Assamese (Kalbitz et al. 2017) macaques.

Macaques are divided into several species-groups, one of which is a sinica species-group composed of Toque macaques (M. sinica) in Sri Lanka, Bonnet macaques (M. radiata) in India, Assamese macaques in India eastward to Southeast Asia, and Tibetan macaques in China (Fooden 1982). Delson (1980) also included stumptail macaques, which are distributed in India eastward to Southeast Asia, in the sinica species-group. Additionally, Arunachal macaques (M. munzala) in the Arunachal area of India and white-cheek macaques (M. leucogenys) in Tibet were recently listed as new species in the sinica species-group (Li et al. 2015; Sinha et al. 2005).

Assamese macaques have been traditionally divided into two subspecies based on their morphological traits (Fooden 1982). Eastern Assamese macaques (M. assamensis assamensis), which inhabit areas east of the Brahmaputra River, have shorter tails than western Assamese macaques (M. a. pelops), which inhabit areas west of the Brahmaputra River (Fooden 1982). Although Assamese macaques are widely distributed in Asia, direct observations of wild Assamese macaques are difficult, because they are patchily distributed in mountainous areas (Chalise et al. 2013; Wada 2005). However, some Assamese macaques are provisioned and habituated to humans at several locations, such as Shivapuri Nagarjun National Park in Nepal (Koirala et al. 2017), Wat Tham Pla in Thailand (Kaewpanus et al. 2015), and Tukreshwari (Tukeswari) Temple in India (Cooper and Bernstein 2000). Provisioned Tibetan macaques have also been observed at Huangshan in China (Ogawa 1995, 2006; Wada et al. 1987).

The present study focuses on comparative observations of the social behaviors of western and eastern Assamese macaques and Tibetan macaques. Similarities and inter-species/subspecies differences among these three macaques are compared, and the potential evolutionary processes involved in the observed social behaviors are discussed.

Materials and methods

Study sites and study subjects

We studied the social behaviors of western and eastern Assamese macaques and Tibetan macaques as described below.

Western Assamese macaques (Macaca assamensis pelops) in Nepal

Nagarjun (27°44′N, 85°17′E, 1350–2093 m above sea level), one of two areas in the Shivapuri Nagarjun National Park, Kathmandu District, Nepal, was selected for this study (Fig. 1, Table 1). The study site is 16 km2 and is covered by mixed broadleaved forests, pine forests, and dry oak forests. Air temperatures ranged from 3.9 to 29.6 °C (Koirala et al. 2017). In addition to several social groups of western Assamese macaques, other mammals, such as rhesus macaques (M. mulatta) and common leopards (Panthera pardus), also inhabit Nagarjun (Chalise et al. 2013; Koirala et al. 2017; Wada 2005).

Eastern Assamese macaques (M. a. assamensis) in Thailand

The study site, Wat Tham Pla (Tham Pla Temple) (20°19′N, 99°51′E, 843 m), is located in Pong Ngam Subdistrict, Mae Sai District, Chiang Rai Province, Thailand (Fig. 1, Table 1). Wat Tham Pla is oriented in front of a steep cliff and a broadleaved forest and is surrounded by a village and cultivated fields. Temperatures at the study site ranged from 23.0 to 33.9 °C during the study periods. The macaques at Wat Tham Pla were originally wild but have been provisioned and habituated to tourists and local people for more than 20 years (Kaewpanus et al. 2015). During the study periods, the macaques slept on steep hills behind the temple at night, and they often stayed in the temple area in the daytime, because they were given food, such as bananas and peanuts, every day. The macaques have no wild predators, but domestic dogs live in the village near the study area.

Females gave birth from April to July and conceived from October to February at Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand (Fürtbauer et al. 2010).

Tibetan macaques (M. thibetana) in China

The study site, called “the valley of monkeys” (30°29′N, 118°11′E, 700–800 m), is located at Huangshan (Mt. Huang) in Anhui Province, China (Fig. 1, Table 1). The 154-km2 Huangshan area is registered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The study site is covered by deciduous and evergreen broadleaved forests. Temperatures at the study site ranged from − 2.0 to 23.0 °C between February and April 1992 and from 4.0 to 27.0 °C between September and November in 1992. Wild Tibetan macaques inhabit this area in several social groups, as do wild rhesus macaques (Wada 2005). No predators of macaques were recorded during the study periods.

Study periods and sampling methods

We directly observed the macaques, using all-occurrence-behavior sampling (Martin and Bateson 1986) throughout the study periods at all three study sites. We recorded all social behaviors involving physical contact, genital showing, and genital inspection between adults within the visual field of the observer(s). We recorded supplanting behavior at the provisioning sites. When Monkey A approached Monkey B, if B immediately withdrew and A took the exact place of B, A was regarded as dominant to B and B was regarded as subordinate to A. We also recorded aggressive (biting, grabbing, hitting, chasing, lunging, open-mouth threat, etc.) and submissive (escaping, grimacing, fearful screaming, etc.) behaviors. We made a winner–loser matrix based on dyadic supplanting and aggressive–submissive interactions, and confirmed the dominance–subordinate relationships between adults.

Additionally, we used focal-animal sampling (Martin and Bateson 1986) of adult males and adult females for 10 h each during both the mating season and the birth season, as macaques are seasonal breeders (Fürtbauer et al. 2010; Li et al. 2005; Xia et al. 2010). During focal-animal sampling, we continuously recorded all social interactions that involved the focal-animal. The study periods during which we conducted focal-animal sampling and the numbers of focal-animals are summarized in Table 1.

In addition to these study periods, (1) Hideshi Ogawa (HO) resided at Nagarjun for a total of 113 days between 2011 and 2017, (2) at Wat Tham Pla for a total of 110 days between 2008 and 2012, and (3) at Huangshan for a total of 382 days between 1989 and 1993. Kazuo Wada resided at Huangshan for a total of 312 days between 1985 and 1988.

Data analyses

We calculated the rate of each social behavior (number of behaviors of each focal-animal/hour) based on focal-animal sampling. We used a Kruskal–Wallis test to examine significant differences in the rate of each behavior among the three macaque species. We used a sign test to examine significant differences between dominant and subordinate individuals. We used a χ2 test to examine significant differences between the observed and expected numbers of behaviors. For statistical tests, we considered p values < 0.05 to indicate statistical significance. When we used multiple tests to examine differences in each behavior in three sex combinations (male–male, male–female, and male–female) during two seasons, we used p values < 0.05/6 = 0.008, because we used a Bonferroni correction.

Study groups

Western Assamese macaques of the AA group in Nepal

Shivapuri Nagarjun National Park harbors a provisioned group of western Assamese macaques, named the “AA group” in the Nagarjun area. The AA group resides in an area near an army camp within the national park. When soldiers at this camp finish breakfast and dinner, they usually dispose of their leftovers at a dumping site in the camp. Macaques in the AA group consume the garbage and have become habituated to humans (Koirala et al. 2017). HO and Sabina Koirala (SK) identified all adult males and females in the AA group based on their physical characteristics. In January 2015, the group was composed of 56 monkeys, with 7 adult males and 13 adult females (Table 2).

Between 2014 and 2017, one adult male immigrated into the AA group, whereas no females immigrated into the AA group. When monkeys disappeared from the AA group, however, we were not sure whether they had died or emigrated from the group. Neither solitary males nor all-male groups have been found in this area (Ogawa et al. 2019). Females give birth from March to July (Ogawa unpublished data). Among adult females in the AA group, the improved Landau’s index (h′) of linearity in a dominance hierarchy (Appleby 1983; de Vries 1995) was 0.98, and hierarchical steepness based on the proportions of wins (Pij) using normalized David’s scores (de Vries et al. 2006) was 0.82 based on 302 supplanting and aggressive–submissive interactions in 2014–2015.

Eastern Assamese macaques of the A, B, C, D groups in Thailand

In Wat Tham Pla, there were 219 monkeys with 26 adult males and 54 adult females in four social groups (A, B, C, and D groups) in January 2012 (Table 2). These macaques formed stable multi-male multi-female groups, although the C group was temporarily a one-male group in 2009. HO identified all adult males and females in these social groups based on their physical characteristics. With the exception of mother–infant relationships, matrilineal kin relations remain unknown. HO did not observe solitary males or all-male groups during the study periods, although several peripheral males sometimes foraged apart from their social group. When monkeys disappeared from the study groups, we were not sure whether they had died or emigrated from the group. When we found a new adult male in the study groups, we were not sure whether he had immigrated into the group or whether a natal juvenile male of the group had become an adult, because HO did not completely identify all immatures. However, at least one adult male transferred from the A group to the D group, and another adult male transferred from the C group to the A group between 2009 and 2012, whereas no females transferred between the study groups. Among adult females in the A group, in which HO observed all adult females for 4 h each in 2009 by focal-animal sampling (Martin and Bateson 1986), the improved Landau’s index (h′) of linearity in a dominance hierarchy (Appleby 1983; de Vries 1995) was 0.83, and hierarchical steepness based on the proportions of wins (Pij) using normalized David’s scores (de Vries et al. 2006) was 0.75 based on 314 supplanting and aggressive–submissive interactions in 2009.

Tibetan macaques of the Yulingkeng group in China

Since 1986, one social group, the Yulingkeng group, has been provisioned for observations at Huangshan. The Yulingkeng group had 42 monkeys with 10 adult males and 9 adult females in November 1992 (Table 2). HO identified all monkeys based on their physical characteristics (Ogawa 2006). The macaques received corn 4 times a day at a feeding station. Matrilineal kinship and population changes in the study group caused by birth, death, and male transfer have been recorded since 1985. Several males immigrated into and disappeared from the Yulingkeng group, whereas females did not immigrate into the group (Ogawa 2006). The mating season occurred from July to December, and the non-mating season lasted from February to June (Li et al. 2005; Xia et al. 2010). Among adult females in the Yulingkeng group, the improved Landau’s index (h′) of linearity in a dominance hierarchy (Appleby 1983; de Vries 1995) was 0.93, and the score of hierarchical steepness based on the proportions of wins (Pij) using normalized David’s scores (de Vries et al. 2006) was 0.66 based on 533 supplanting and aggressive–submissive interactions in 1992. The score of hierarchical steepness was 0.87 based on the proportions of wins (Pij) and 0.96 based on the dyadic dominance index (Dij), and the percentage of counter aggression was 0.76 among adult females in the same group in 1991 (Ogawa 1995; Balasubramaniam et al. 2012).

Results

During focal-animal sampling and all-occurrence-behavior sampling, we recorded a total of 9843 behavioral events involving physical contact between adults: 1984 events for western Assamese macaques, 3577 for eastern Assamese macaques, and 4282 for Tibetan macaques. Macaques performed hugging, genital touching, genital sucking, bridging, mounting, copulation, and social grooming, as well as aggressive behaviors with physical contact. Macaques also performed genital showing and genital inspection.

Affiliative and reproductive behavior between adults

We compared the presence/absence of each behavior using the all-occurrence-behavior sampling, whereas the rate of each behavior was analyzed using focal-animal sampling (Table 3). Figures 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 show affiliated and sexual behaviors of Assamese and Tibetan macaques, although some of the individuals in the video images are not adults.

Genital touching of Macaca assamensis assamensis. An adult male touched the penis of a juvenile male (http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430ma09a)

Genital sucking of Macaca thibetana. Two juvenile males hugged each other and mutually sucked the penis of the other male (http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430mt06a)

Bridging behavior of Macaca thibetana. Two adult males simultaneously lifted a male infant between them, turned the infant face up, and touched and sucked the infant’s penis (http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430mt01ba)

Bridging behavior of Macaca assamensis assamensis. Two adult males simultaneously lifted a male infant between them and touched and sucked the infant’s penis (http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430ma01ba)

Presenting behavior of Macaca assamensis assamensis. An approaching female turned her buttocks to another female (http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430ma10a)

Genital inspection of Macaca assamensis assamensis. An adult male inspected a female’s genitalia (http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430ma04a)

Mounting behavior of Macaca assamensis assamensis. An adult male mounted another adult male and the mounting male touched the penis and testes of the other male (http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430ma07a)

Hugging

Hugging is defined as using hands to hold the body of another individual and making physical contact with the individual.

Between adult males

Males in all three macaque species hugged facing each other. Male Tibetan macaques usually shook their bodies when they were hugging, whereas the two subspecies of male Assamese macaques did not. Male Assamese macaques sometimes clung to another male’s back and shoulder with their hands, whereas male Tibetan macaques rarely did so but usually hugged facing each other.

Between adult females

Females of all three macaque species hugged another female. Female eastern Assamese macaques sometimes hugged each other while face to face. Female Tibetan macaques frequently hugged another female, but only when their dominance relationships were unstable (Ogawa 2006).

Between adult males and adult females

Males and females in all three macaque species used their hands to hug each other.

Genital touching

Genital touching is generally defined as touching the penis and testes of another male with the fingers (penis touching), or touching the genitalia of another female with the fingers. However, when monkeys touched the genitalia of another individual during hugging, mounting, or genital inspection, this was not classified as genital touching.

Between adult males

Males in all three macaque species touched the penis and testes of another male with their fingers. Male Tibetan macaques sometimes touched the penis and testes of another male when they were hugging each other. By contrast, male Assamese macaques frequently extended their arm and touched the penis and testes of another male (Fig. 2; http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430ma09a). Males of all three macaque species frequently touched the penis and testes of another male when they mounted another male or were mounted by another male (see below).

Between adult females

None of the females in any of the three macaque species touched the genitalia of another female, although females did inspect the genitalia of another female (see below).

Between adult males and adult females

None of the males in any of the three macaque species touched a female’s genitalia, except for genital inspection. No females in any of the three macaque species touched a male’s penis.

Genital sucking

Genital sucking is defined as sucking the penis and testes of a male (penis sucking), or sucking the genitalia of a female.

Between adult males

Only male Tibetan macaques sucked the penis of another adult male. When one of the males lay down on his back and the other male put his head between the legs of the former male, the latter male moved his lips and sucked the tip of the penis of the former male. Male Tibetan macaques occasionally hugged each other and mutually sucked the penis of the other male (Fig. 3; http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430mt06a). Neither western nor eastern Assamese male macaques sucked the penis of another adult male, although males of eastern Assamese macaques sucked the genitalia of male and female infants (see below).

Between adult females

None of females in any of the three macaque species sucked the genitalia of another female, although they occasionally licked a secretion on the genitalia of another female during genital inspection (see below).

Between adult males and adult females

None of the males in any of the three macaque species sucked a female’s genitalia, except for genital inspection. Neither western nor eastern Assamese female macaques sucked a male’s penis, and we recorded only one event in which a female Tibetan macaque sucked a male’s penis.

Bridging

Bridging is defined as two individuals simultaneously lifting an infant.

Between adult males

Bridging behavior was recorded in males of both Tibetan macaques (Fig. 4; http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430mt01a) and eastern Assamese macaques (Fig. 5; http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430ma01a). That is, two males of these macaque species simultaneously lifted an infant between them when the male who was holding the infant approached another male or was approached by another male. One or both of the males frequently touched and/or sucked the genitalia of the infant during bridging. Both macaques used a male infant in bridging more frequently than expected considering the number of male and female infants in the study group (chi-square test, df = 1, χ2 = 19.5, p < 0.05 for eastern Assamese macaques; df = 1, χ2 = 70.2, p < 0.05 for Tibetan macaques). Male Tibetan macaques usually turned the infant face up, whereas male eastern Assamese macaques did not necessarily do so. In contrast to Tibetan and eastern Assamese macaques, male western Assamese macaques never performed bridging behavior. The rate of bridging behavior between adult males was significantly higher in Tibetan and eastern Assamese macaques than in western Assamese macaques, who did not perform bridging behavior (Kruskal–Wallis test, n1 = 7, n2 = 10, n3 = 5, H = 12.964, p < 0.008 during the birth season; n1 = 7, n2 = 5, n3 = 6, H = 13.112, p < 0.008 during the mating season, Table 3).

Between adult females

Female Tibetan and eastern Assamese macaques performed bridging behavior with females. When a mother was holding her infant offspring, another female approached the mother, clasped the infant’s leg, and lifted the infant with the mother. One or both of the females touched and/or sucked the genitalia of the infant. Female Tibetan macaques used a male infant more frequently than expected (chi-square test, df = 1, χ2 = 53.8, p < 0.05), but no significant sex difference was found in eastern Assamese macaques (chi-square test, df = 1, χ2 = 1.1, n.s.). Female western Assamese macaques did not perform bridging behavior. The rate of bridging behavior between females was significantly higher in Tibetan and eastern Assamese macaques than in western Assamese macaques, who did not perform bridging behavior (Kruskal–Wallis test, n1 = 7, n2 = 10, n3 = 9, H = 12.341, p < 0.008 during the birth season; n1 = 7, n2 = 5, n3 = 9, H = 10.189, p < 0.05 during the mating season, Table 3).

Between adult males and adult females

Bridging behavior was recorded between males and females in Tibetan and eastern Assamese macaques. When a mother was holding her offspring infant, a male approached the mother, clasped the infant’s leg, and simultaneously lifted the infant with the mother. Males sometimes carried an infant to its mother and lifted it with the mother. One or both of the individuals touched and/or sucked the genitalia of the infant. Male and female Tibetan macaques used a male infant more frequently than expected (chi-square test, df = 1, χ2 = 232.7, p < 0.05), but the difference could not be tested in eastern Assamese macaques due to a small sample size. Western Assamese macaques did not perform bridging behavior between males and females. The rate of bridging behavior between males and females was significantly higher in Tibetan and eastern Assamese macaques than in western Assamese macaques during the birth season, although the rate did not significantly differ during the mating season (Kruskal–Wallis test, n1 = 14, n2 = 20, n3 = 14, H = 12.741, p < 0.008 during the birth season; n1 = 14, n2 = 10, n3 = 15, H = 2.785, n.s. during the mating season, Table 3).

Genital showing (penis showing and presenting)

Penis showing is defined as the behavior in which males in a quadrupedal posture raise one of their legs and show their penis to another individual. Presenting is defined as the behavior in which males or females in a quadrupedal posture turn their buttocks to another individual and take the same posture as female monkeys do for copulation.

Between adult males

Males of all three macaque species performed penis showing behavior to another male. Males of all three macaque species also performed presenting behavior. In addition to subordinate males, dominant males performed presenting behavior to their subordinate male to solicit mounting.

Between adult females

Females in all three macaque species performed presenting behavior in which they turned their buttocks to another female (Fig. 6; http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430ma10a). Females in eastern Assamese macaques performed presenting behavior to another female more frequently than other macaque species in the birth season, although the rate did not significantly differ during the mating season (Kruskal–Wallis test, n1 = 7, n2 = 10, n3 = 9, H = 9.876, p < 0.008 during the birth season; n1 = 14, n2 = 10, n3 = 15, H = 0.101, n.s. during the mating season, Table 3).

Between adult males and adult females

None of the males in any of the three macaque species raised his leg and showed his penis to a female. None of the males in any of the macaque species turned his buttocks toward a female. Females in all three macaque species turned their buttocks toward males.

Genital inspection

Genital inspection is defined as the behavior in which males or females bring their face close to the genitalia of another individual and carefully look at the genitalia, sometimes while smelling, touching the genitalia with their fingers, licking a secretion on their fingers, and occasionally making physical contact between their month and the female genitalia to directly lick a secretion on the genitalia. However, oral–genital contact during genital inspection was not classified as genital sucking.

Between adult males

Although males and females both inspected female genitalia, no males of the three macaque species inspected the penis of another male. When males touched the penis of another male (penis touching behavior), they did not carefully look at or smell it.

Between adult females

Females in all three macaque species stared at, smelled, and/or touched the genitalia of another female, and occasionally licked a secretion on the genitalia of another female. Dominant females inspected her subordinate female’s genitalia, whereas subordinate females did not inspect her dominant female’s genitalia (sign test, n1 = 4, n2 = 0, n.s. for western Assamese macaques; n1 = 13, n2 = 0, p < 0.05 for eastern Assamese macaques; n1 = 29, n2 = 0, p < 0.05 for Tibetan macaques). Females inspected the genitalia of another female during both the birth and mating seasons. The significance of the difference between the two seasons could not be examined, due to the small sample size.

Between adult males and adult females

Males in all three macaque species inspected a female’s genitalia (Fig. 7; http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430ma04a). That is, males carefully looked at, smelled, touched with their fingers, licked a secretion on their fingers, and/or licked a secretion on female genitalia. They performed this behavior more frequently during the mating season than during the birth season, although the difference was not significant for Tibetan macaques (chi-square test, df = 1, χ2 = 50.5, p < 0.05 for western Assamese macaques; χ2 = 19.9, p < 0.05 for eastern Assamese macaques; χ2 = 0.03, n.s. for Tibetan macaques). No females in any of the three macaque species inspected a male’s penis.

Mounting

Mounting is defined as the behavior in which males or females mount another individual, by clasping the feet of the recipient with their toes, and taking the same posture as copulation without inserting the penis into the female’s vagina even if the mounter is a male.

Between adult males

Males of all three macaque species mounted another male. During mounting, one male used his toes to grasp the other male’s legs and mounted the back of the other male, which is a posture similar to that of copulation (Fig. 8; http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php%3fmovieid%3dmomo090430ma07a). Both the mounting and mounted males frequently touched the penis and testes of the other male, but did not touch their own penis or testes during mounting. They did not perform pelvic thrust and did not ejaculate during mounting. Anal penetration was never recorded. Not only did a dominant male mount his subordinate male but a subordinate male would also mount his dominant male. A dominant male did not mount his subordinate male more frequently than vice versa (sign test, n1 = 22, n2 = 34, n.s. for western Assamese macaques; n1 = 55, n2 = 49, n.s. for eastern Assamese macaques; n1 = 43, n2 = 50, n.s. for Tibetan macaques).

Between adult females

Female western and eastern Assamese macaques occasionally mounted another female. Only dominant females mounted subordinate females in eastern Assamese macaques (sign test, n1 = 12, n2 = 0, p < 0.05). We recorded one event in which a dominant female western Assamese macaque mounted her subordinate female, but we did not record a subordinate female mounting a dominant female. Female Tibetan macaques did not mount another female, with the exception of one female that frequently mounted another female between December 1990 and April 1991 (Ogawa 2006). When the dominance relationships were unstable in December 1990, instead of mounting, female Tibetan macaques performed hold-bottom behavior in which a female macaque did not mount but scratched another female’s buttocks with her toes while clunging to the back of the other female with her hands from a sitting position behind the other female (Ogawa 2006). We did not record hold-bottom behavior in western or eastern Assamese macaques. None of the females in any of the three macaque species rubbed their genitals on the body of another female or showed signs of orgasm during the mounting and hold-bottom behavior.

Between adult males and adult females

Males in all three macaque species occasionally mounted a female macaque. Because observers were unable to distinguish between social and sexual mounts, both are counted as mounting in Table 3. Female eastern Assamese macaques occasionally mounted a male macaque. However, neither western Assamese nor Tibetan macaque females mounted a male macaque.

Copulation

Copulation was defined as a male macaque mounting a female macaque and inserting his penis into the female’s vagina.

Between adult males and adult females

Males in all three macaque species copulated with females and ejaculated in a single mount. After the male finished thrusting his penis, he sometimes did not (or could not) immediately pull his penis out of the vagina and remained in that posture for a while (Li et al. 2005), like stumptail macaques (Brereton 1994).

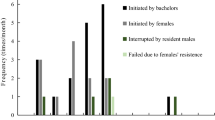

Social grooming between adults

Figure 9 presents the rate of social grooming between males, between females, and between males and females during each season. Grooming bouts were more frequently recorded between females than between males (chi-square test, df = 1, χ2 = 170.2, p < 0.05 for western Assamese macaques; χ2 = 123.8, p < 0.05 for eastern Assamese macaques; χ2 = 69.7, p < 0.05 for Tibetan macaques). Females groomed males more frequently than vice versa during the birth season (chi-square test, df = 1, χ2 = 8.3, p < 0.05 for western Assamese macaques; χ2 = 33.3, p < 0.05 for eastern Assamese macaques; χ2 = 29.8 for Tibetan macaques), but the difference was not significant during the mating season for western and eastern Assamese macaques (chi-square test, df = 1, χ2 = 1.4, n.s. for western Assamese macaques; χ2 = 0.0, n.s. for eastern Assamese macaques; χ2 = 5.9, p < 0.05 for Tibetan macaques). The lack of a difference during the mating season is due, in part, to the fact that males groomed females during the mating season more frequently than they did during the birth season (chi-square test, df = 1, χ2 = 50.9, p < 0.05 for western Assamese macaques; χ2 = 27.7, p < 0.05 for eastern Assamese macaques; χ2 = 12.0 for Tibetan macaques), whereas females did not necessarily groom males more frequently during the mating season than they did during the birth season (chi-square test, df = 1, χ2 = 33.3, p < 0.05 for western Assamese macaques; χ2 = 0.0, n.s. for eastern Assamese macaques; χ2 = 2.7, n.s. in Tibetan macaques).

Rate of grooming between adults of Macaca assamensis pelops, M. a. assamensis, and M. thibetana. a Social grooming between males. b Social grooming between females. c Social grooming from male to female. d Social grooming from female to male. Rate of behavior = number of grooming bouts/hour. One bout is a contentious grooming without a > 10-s pause

Dyadic infant handling by adult males

Table 4 presents the rate of social behaviors by adult males toward infants based on focal-animal sampling.

Genital touching

Males in all three macaque species touched the genitalia of an infant during dyadic interactions. Male eastern Assamese and Tibetan macaques did so during bridging behavior as well (see above).

Genital sucking

Male Tibetan and eastern Assamese macaques sucked the genitalia of an infant during dyadic interactions as well as during bridging behavior (see above). They sometimes turned the infant upside down. The infant sometimes jumped onto an adult male’s face to have his penis sucked. Male western Assamese macaques did not suck the genitalia of infants.

Holding

Males in all three macaque species held an infant.

Social grooming

Males in all three macaque species groomed an infant.

Discussion

The age and sex compositions of the study groups show that western Assamese macaques in Nepal, eastern Assamese macaques in Thailand, and Tibetan macaques in China all form multi-male multi-female social groups. The records of transfer between social groups indicate that all macaque species form groups with female philopatry and male dispersal (Ogawa 2006). The social relationships within these groups were also similar to one another: each had a linear dominance hierarchy among adult females and kin-biased relationships among females (Balasubramaniam et al. 2012, 2018). The relative frequencies of social grooming between males, between females, and between males and females were similar in the three species. Cooper and Bernstein (2000) reported that adult male Assamese macaques at the Tukeswari (Tukreshwari) Temple in the West Bengal state in India groomed adult females more frequently than the reverse. In the present study, however, neither western nor eastern male Assamese macaques groomed females more frequently than vice versa, which is common among macaque species.

One of the conspicuous features of the social behavior of these macaque species is that they performed various affiliative behaviors with physical contact between adult males, between adult females, and between adult males and adult females. Additionally, they touched the genitalia of another individual during the interactions. A variety of genital contact behaviors have been reported in other primates (Dixson 1998; Vasey 1995). For example, pygmy chimpanzees (Pan paniscus) perform gg (genito–genital) rubbing behavior between females and rump–rump contact between males (Kano 1980; Kuroda 1980). However, none of the three macaque species made genital–genital contact. Unlike kissing in humans (Homo sapiens), none of the three macaque species made oral–oral contact, although western and eastern Assamese macaques sometimes put their lips on or very close to the body of another individual (Ogawa unpublised data). Instead, when they showed affiliative behaviors such as hugging and mounting, they frequently touched the genitalia of the other individual. In addition, eastern Assamese and Tibetan macaques sucked the genitalia of infants, and male Tibetan macaques sucked the penises of other adult males.

In addition to copulation, some of the male–female interactions involving genital contact could be regarded as reproductive efforts. During some interactions involving a male macaque mounting a female, the male did not actually insert his penis into the female’s vagina, primarily because the female rejected copulation. Males inspected a female’s genitalia more frequently during the mating season than during the birth season, whereas females did not inspect a male’s penis. These findings indicate that males may try to monitor the timing of ovulation in the female sexual cycle.

On the other hand, other behaviors that involved genital contact, such as penis sucking, penis touching, hugging, and mounting, did not appear to be reproductive efforts but rather ritualized affiliative behaviors (Ogawa 1995, 2006). During genital contact, males did not engage in pelvic thrusts or ejaculation, and females did not rub their genitals or show signs of orgasm. Unlike the mounting between female Japanese macaques (Vasey 2006), the genital contact behaviors of the three macaque species in the present study may serve social functions in that they may regulate social relationships with another individual. Only dominant females inspected the genitalia of another female. Females might assert their dominance rank via genital inspection rather than by monitoring the sexual cycles of another female. In contrast to female genital inspection, the mounting rate of the dominant male onto the subordinate male did not differ from the reverse interaction, indicating that these males were not asserting their dominance rank by mounting.

We also observed several differences in genital contact behaviors among the three macaque species. Bridging behavior was recorded between males, between females and between males and females in Tibetan macaques (this study; Ogawa 1995, 2006) and in eastern Assamese macaques in Thailand (this study; Kalbitz et al. 2017). Males in these macaque species also sucked the genitalia of an infant during bridging behavior and during dyadic interactions with an infant. The nature of bridging did differ somewhat between eastern Assamese macaques and Tibetan macaques. Although males do not necessarily have to turn the infant face up in order to suck the genitalia of the infant, male Tibetan macaques usually turned the infant face up, whereas male eastern Assamese macaques did not necessarily do so. Bridging appeared to be more ritualized in Tibetan macaques than in eastern Assamese macaques. Additionally, only male Tibetan macaques directly sucked the penis of another adult male.

In contrast to eastern Assamese and Tibetan macaques, western Assamese macaques in Nepal did not perform either bridging or genital sucking. The absence of a certain behavior cannot be logically demonstrated. At the very least, however, western Assamese macaques performed these behaviors significantly less frequently compared to Tibetan and eastern Assamese macaques. Additionally, field observations at Ramdi Village (27°54′N, 83°38′E), Pyuthan District, Nepal and at Wat Tham Pha Tha Pol (16°31′N, 100°40′E), Phitsanulok Province, Thailand, supported our observations that eastern Assamese macaques engage in bridging behavior, whereas western Assamese macaques do not (Ogawa et al. 2019). The occurrence of bridging and genital sucking behaviors in Tibetan and eastern Assamese macaques is generally consistent with genetic and morphological evidence that Tibetan and eastern Assamese macaques share a close phylogenetic relationship (Biswas et al. 2011; Sukmak et al. 2014). Assuming that Tibetan macaques split from eastern Assamese macaques, bridging and genital sucking behaviors may have evolved in the clade containing Tibetan and eastern Assamese macaques in the sinica species-group, although it is also possible that western Assamese macaques lost the bridging behavior. On the other hand, the fact that only western Assamese macaques in Nepal did not exhibit bridging behavior is consistent with a genetic study demonstrating that the Nepal population of Assamese macaques was unique in its genetic diversity compared to other populations (Khanal et al. 2018).

Similar to Tibetan and eastern Assamese macaques, stumptail and Barbary macaques also exhibit a behavior similar to bridging. Two female stumptail macaques handle a newborn baby together (Estrada and Sandoval 1977; Chokechaipaisarn et al. 2016). Male Barbary macaques handle an infant together, which is referred to as “triadic male–infant interaction” and “agonistic buffering” (Deag and Crook 1971; Paul 1999; Taub 1980). Such interactions have rarely been reported in other species-groups of macaques. These findings suggest that the origin of these behaviors may have occurred in the common ancestral species of the sinica species-group (possibly including the clade containing stumptail and Barbary macaques) and that some species lost the behavior while others evolved a more ritualized version of the behavior. To determine whether these behaviors are homologous or analogous, further studies are needed in other populations of Assamese macaques and other macaques of the sinica species-group.

References

Appleby MC (1983) The probability of linearity in hierarchies. Anim Behav 31:600–608

Balasubramaniam KN, Dittmar K, Berman CM, Butovskaya M, Cooper MA, Majolo B, Ogawa H, Schino G, Thierry B, de Waal FBM (2012) Hierarchical steepness and phylogenetic models: phylogenetic signals in Macaca. Anim Behav 83:1207–1218

Balasubramaniam KN, Beisner BA, Berman CM, De Marco A, Duboscq J, Koirala S, Majolo B, MacIntosh AJJ, McFarland R, Molesti S, Ogawa H, Petit O, Schino G, Sosa S, Sueur C, Thierry B, de Waal FBM, McCowan BJ (2018) The influence of phylogeny, social style, and sociodemographic factors on variation in macaque social networks. Am J Primatol 80:e22727

Berman CM, Thierry B (2010) Variation in kin bias: species differences and time constraints in macaques. Behaviour 147:1863–1887

Biswas J, Borah DK, Das A, Das J, Bhattacharjee PC, Mohnot SM, Horwich RH (2011) The enigmatic Arunachal macaque: its biogeography, biology and taxonomy in northeastern India. Am J Primatol 73:1–16

Brereton AR (1994) Copulatory behavior in a free-ranging population of stumptail macaques (Macaca arctoides) in Mexico. Primates 35(2):113–122

Chalise M, Ogawa H, Pandey B (2013) Assamese monkeys in Nagarjun forest of Shivapuri Nagarjun National Park, Nepal. Tribhuvan Univ J 28(1–2):181–190

Chokechaipaisarn C, Toyoda A, Malaivijitnond S (2016) Preliminary study on agonistic buffering behaviors in stump-tailed macaque (Macaca arctoides). In: 5th Asian Primate Symposium, Sri Lanka, 19–21 October 2016

Cooper MA, Bernstein IS (2000) Social grooming in Assamese macaques (Macaca assamensis). Am J Primatol 50:77–85

de Vries H (1995) An improved test of linearity in dominance hierarchies containing unknown or tied relationships. Anim Behav 50:1375–1389

de Vries H, Stevens JMG, Vervaecke H (2006) Measuring and testing the steepness of dominance hierarchies. Anim Behav 71:585–592

de Waal FBM, Luttrell LM (1989) Toward a comparative socioecology of the genus Macaca: different dominance styles in rhesus and stumptail monkeys. Am J Primatol 19:83–109

Deag JM, Crook JH (1971) Social behaviour and “agonistic buffering” in the wild Barbary macaques, Macaca sylvana L. Folia Primatol 15:183–200

Delson E (1980) Fossil macaques, phyletic relationships and a scenario of deployment. In: Lindburg D (ed) The macaques: studies in ecology, behavior and evolution. Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, pp 10–30

Dixson AF (1998) Primate sexuality: comparative studies of the prosimians, monkeys, apes, and human beings. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Estrada A, Sandoval JM (1977) Social relationships in a free-ranging troop of stumptail macaques (Macaca arctoides): male-care behavior I. Primates 18:783–813

Fooden J (1982) Taxonomy and evolution of the sinica group of macaques: 3. Species and subspecies accounts of Macaca assamensis. Fieldiana Zool (New Series) 10:1–52

Fürtbauer I, Schülke O, Heistermann M, Ostner J (2010) Reproductive and life history parameters of wild female Macaca assamensis. Int J Primatol 31:501–517

Kaewpanus K, Aggimarangsee N, Sitasuwan N, Wangpakattanawong P (2015) Diet and feeding behavior of Assamese macaques (Macaca assamensis) at Tham Pla temple, Chiang Rai Province, northern Thailand. J Wildl Thail 22(1):23–35

Kalbitz J, SchuÈlke O, Ostner J (2017) Triadic male–infant–male interaction serves in bond maintenance in male Assamese macaques. PLoS One 12(10):e0183981

Kano T (1980) Social behavior of wild pygmy chimpanzees (Pan paniscus) of Wamba. J Hum Evolut 9(4):243–254

Khanal L, Chalise MK, Hei K, Acharya BK, Kawamoto Y, Jiang X (2018) Mitochondrial DNA analyses and ecological niche modeling reveal post-LGM expansion of the Assam macaque (Macaca assamensis) in the foothills of Nepal Himalaya. Am J Primatol. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.22748

Koirala S, Chalise MK, Katuwal H, Gaire R, Pandey B, Ogawa H (2017) Diet and activity of Macaca assamensis in wild and semi-provisioned groups in Shivapuri Nagarjun National Park, Nepal. Folia Primatol 88:57–74

Kuroda S (1980) Social behavior of the pygmy chimpanzee. Primates 21:181–197

Li J, Yin H, Wang Q (2005) Seasonality of reproduction and sexual activity in female Tibetan macaques Macaca thibetana at Huangshan, China. Acta Zool Sin 51:365–375

Li C, Chao Z, Fan P (2015) White-cheeked macaques (Macaca leucogenys): a new macaque species from Modog, Southeastern Tibet. Am J Primatol 77(2):753–766

Martin P, Bateson P (1986) Measuring behavior: an introductory guide. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Mori A (1983) Comparison of the communicative vocalizations and behaviors of group ranging in eastern gorillas, chimpanzees and pygmy chimpanzees. Primates 24(4):486–500

Ogawa H (1995) Bridging behavior and other affiliative interactions among male Tibetan macaques (Macaca thibetana). Int J Primatol 16:707–729

Ogawa H (2006) Wily monkeys: social intelligence of Tibetan macaques. Kyoto University Press, Kyoto

Ogawa H (unpublised data) Bridging behavior and male-infant interactions in Macaca thibetana and M. assamensis: insight into the evolution of social behavior in the sinica species-group of macaques. In: Li J, Sun L, Kappeler PM (eds) Behavioral ecology of Tibetan macaques. Springer, New York (In press)

Ogawa H, Paudel PK, Koirala S, Khatiwada S, Chalise MK (2019) Social interactions between rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) and Assamese macaques (M. assamensis) in Nepal: why do male rhesus macaques follow social groups of Assamese macaques? Primate Res (In press)

Paul A (1999) The sociobiology of infant handling in primates: is the current model convicing? Primates 40:33–46

Sinha A, Datta A, Madhusudan MD, Mishra C (2005) Macaca munzala: a new species from western Arunachal Pradesh, northeastern India. Int J Primatol 26(4):977–989

Sukmak M, Malaivijitnond S, Schülke O, Ostner J, Hamada Y, Wajjwalku W (2014) Preliminary study of the genetic diversity of eastern Assamese macaques (Macaca assamensis assamensis) in Thailand based on mitochondrial DNA and microsatellite markers. Primates 55:189–197

Taub DM (1980) Testing the “agonistic buffering” hypothesis. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 6:187–197

Thierry B, Singh M, Kaumanns W (eds) (2004) Macaque societies: a model for the study of social organization. Cambridge University Press

Vasey PL (1995) Homosexual behavior in primates: a review of evidence and theory. Int J Primatol 16:173–204

Vasey PL (2006) The pursuit of pleasure: an evolutionary history of female homosexual behaviour in Japanese macaques. In: Sommer V, Vasey PL (eds) Homosexual behaviour in animals: an evolutionary perspective. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 191–219

Wada K (2005) The distribution pattern of rhesus and Assamese monkeys in Nepal. Primates 46:115–119

Wada K, Xiong CP, Wang QS (1987) On the distribution of Tibetan and rhesus monkeys in Southern Anhui province, China. Acta Theriologica Sinica 7:148–176

Xia D, Li J, Zhu Y, Sun B, Sheeran LK, Matheson MD (2010) Seasonal variation and synchronization of sexual behaviors in free-ranging male Tibetan macaques (Macaca thibetana) at Huangshan, China. Zool Res 5:509–515

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Mr. B. Pandey at the National Trust for Nature Conservation and Dr. Y. Kawamoto at Kyoto University, Mr. Chandra Budhathoiki, Mr. Kishor Lama, and other park rangers and staff of Shivapuri Nagarjun National Park for their kind cooperation and for their valuable suggestions regarding the study in Nepal, authorized by the Department of National Park and Wildlife Conservation and Nepal Biodiversity Research Society; Prof. S. Hannongbua at Chulalongkorn University and Mr. L. Por, Mr. S. Win, Mr. S. Tirapanyo, and Mr. I. Ito, chief monks of Wat Tham Pla, and Mr. Komkrich Kaewpanus at Chiang Mai University for their kind cooperation with the field survey in Thailand permitted by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT); Prof. Q. Wang, Mr. C. Xiong, Dr. J. Li, Dr. M. Li, at Anhui University and Mr. S. Zheng at Huangshan for their support of the study in China; and Dr. K. Balasubramaniam and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on the manuscript. This study was financially supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant numbers JP25440253 and JP16K07539 (in Nepal); JSPS KAKENHI Grant number 20255006 (in Thailand); and the Takashima Fund of the Primate Society of Japan and JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) (in China).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ogawa, H., Chalise, M.K., Malaivijitnond, S. et al. Comparison of genital contact behaviors among Macaca assamensis pelops in Nepal, M. a. assamensis in Thailand, and M. thibetana in China. J Ethol 37, 243–258 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10164-019-00595-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10164-019-00595-5