Abstract

Background

The dicarbonyl methylglyoxal reacts primarily with arginine residues to form advanced glycation end products, including Nδ-(5-hydro-5-methyl-4 -imidazolone-2-yl)-ornithine (MG-H1), which are risk factors for not only diabetic complications but also lifestyle-related disease including renal dysfunction. However, the data on serum level and clinical significance of this substance in chronic kidney disease are limited.

Methods

Serum levels of MG-H1 and Nε-(carboxymethyl) lysine (CML) in 50 patients with renal dysfunction were measured by liquid chromatography/triple-quadruple mass spectrometry.

Results

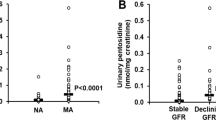

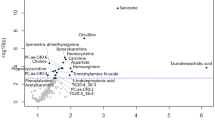

The median serum MG-H1 levels in patients with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of ≥30, 15–30, and <15 ml/min/1.73 m2 was 4.16, 12.58, and 14.66 mmol/mol Lys, respectively (p > 0.05). On the other hand, MG-H1 levels in patients with HbA1c of <6 and ≥6 % was 12.85 and 10.45 mmol/mol Lys, respectively, the difference between which is not significant. In logistic regression analysis, decreased renal function (eGFR <15 ml/min/1.73 m2) significantly associated with high serum levels of MG-H1 [odds ratio: 9.39 (95 % confidence interval 1.528–57.76), p = 0.015; Spearman rank correlation: MG-H1 vs. eGFR, r = −0.691, p < 0.01]. In contrast, the serum level of CML did not correlate with eGFR, but correlated with systolic blood pressure [odds ratio 16.17 (95 % confidence interval 1.973–132.5), p = 0.010; Spearman rank correlation coefficient: CML vs. eGFR, r = 0.454, p < 0.01].

Conclusion

These results showed that the serum concentration of MG-H1 was strongly related to renal function rather than to DM.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature. 2001;414(6865):813–20.

Peppa M, Uribarri J, Vlassara H. The role of advanced glycation end products in the development of atherosclerosis. Curr Diabetes Rep. 2004;4(1):31–6.

Thornalley PJ, Langborg A, Minhas HS. Formation of glyoxal, methylglyoxal and 3-deoxyglucosone in the glycation of proteins by glucose. Biochem J. 1999;344(Pt 1):109–16.

Nagai R, Unno Y, Hayashi MC, Masuda S, Hayase F, Kinae N et al. Peroxynitrite induces formation of N(epsilon)-(carboxymethyl) lysine by the cleavage of Amadori product and generation of glucosone and glyoxal from glucose: novel pathways for protein modification by peroxynitrite. Diabetes. 2002;51(9):2833–9.

Nagai R, Hayashi CM, Xia L, Takeya M, Horiuchi S. Identification in human atherosclerotic lesions of GA-pyridine, a novel structure derived from glycolaldehyde-modified proteins. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(50):48905–12.

Brouwers O, Niessen PM, Ferreira I, Miyata T, Scheffer PG, Teerlink T et al. Overexpression of glyoxalase-I reduces hyperglycemia-induced levels of advanced glycation end products and oxidative stress in diabetic rats. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(2):1374–80. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.144097.

Makino H, Shikata K, Hironaka K, Kushiro M, Yamasaki Y, Sugimoto H et al. Ultrastructure of nonenzymatically glycated mesangial matrix in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 1995;48(2):517–26.

Matafome P, Sena C, Seica R. Methylglyoxal, obesity, and diabetes. Endocrine. 2013;43(3):472–84. doi:10.1007/s12020-012-9795-8.

Hanssen NM, Stehouwer CD, Schalkwijk CG. Methylglyoxal and glyoxalase I in atherosclerosis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2014;42(2):443–9. doi:10.1042/BST20140001.

Srikanth V, Westcott B, Forbes J, Phan TG, Beare R, Venn A et al. Methylglyoxal, cognitive function and cerebral atrophy in older people. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(1):68–73. doi:10.1093/gerona/gls100.

Lu J, Randell E, Han Y, Adeli K, Krahn J, Meng QH. Increased plasma methylglyoxal level, inflammation, and vascular endothelial dysfunction in diabetic nephropathy. Clin Biochem. 2011;44(4):307–11. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.11.004.

Oya T, Hattori N, Mizuno Y, Miyata S, Maeda S, Osawa T et al. Methylglyoxal modification of protein. Chemical and immunochemical characterization of methylglyoxal-arginine adducts. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(26):18492–502.

Ahmed N, Thornalley PJ, Dawczynski J, Franke S, Strobel J, Stein G et al. Methylglyoxal-derived hydroimidazolone advanced glycation end-products of human lens proteins. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(12):5287–92.

Beisswenger PJ, Howell SK, Russell GB, Miller ME, Rich SS, Mauer M. Early progression of diabetic nephropathy correlates with methylglyoxal-derived advanced glycation end products. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(10):3234–9. doi:10.2337/dc12-2689.

Randell EW, Vasdev S, Gill V. Measurement of methylglyoxal in rat tissues by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2005;51(2):153–7.

Seino Y, Nanjo K, Tajima N, Kadowaki T, Kashiwagi A, Araki E et al. Report of the committee on the classification and diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig. 2010;1(5):212–28. doi:10.1111/j.2040-1124.2010.00074.x.

Matsuo S, Imai E, Horio M, Yasuda Y, Tomita K, Nitta K et al. Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(6):982–92. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.12.034.

Jo-Watanabe A, Ohse T, Nishimatsu H, Takahashi M, Ikeda Y, Wada T et al. Glyoxalase I reduces glycative and oxidative stress and prevents age-related endothelial dysfunction through modulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation. Aging Cell. 2014;13(3):519–28. doi:10.1111/acel.12204.

Nakano M, Kubota M, Owada S, Nagai R. The pentosidine concentration in human blood specimens is affected by heating. Amino Acids. 2013;44:1451–6. doi:10.1007/s00726-011-1180-z.

Frizzell N, Rajesh M, Jepson MJ, Nagai R, Carson JA, Thorpe SR et al. Succination of thiol groups in adipose tissue proteins in diabetes: succination inhibits polymerization and secretion of adiponectin. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(38):25772–81. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.019257.

McLellan AC, Thornalley PJ, Benn J, Sonksen PH. Glyoxalase system in clinical diabetes mellitus and correlation with diabetic complications. Clinical Sci (Lond). 1994;87(1):21–9.

Scheijen JL, Schalkwijk CG. Quantification of glyoxal, methylglyoxal and 3-deoxyglucosone in blood and plasma by ultra performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry: evaluation of blood specimen. Clin Chem Lab Med CCLM/FESCC. 2014;52(1):85–91. doi:10.1515/cclm-2012-0878.

Genuth S, Sun W, Cleary P, Gao X, Sell DR, Lachin J et al. Skin advanced glycation end products glucosepane and methylglyoxal hydroimidazolone are independently associated with long-term microvascular complication progression of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2015;64(1):266–78. doi:10.2337/db14-0215.

Dworacka M, Winiarska H, Szymanska M, Szczawinska K, Wierusz-Wysocka B. Serum N-epsilon-(carboxymethyl)lysine is elevated in nondiabetic coronary heart disease patients. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;13(3):201–13.

Inoue R, Sakata N, Nakai K, Aikawa H, Tsutsumi M, Nii K et al. Nepsilon-(Carboxymethyl)lysine in debris from carotid artery stenting: multiple versus nonmultiple postoperative lesions. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23(10):2827–33. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.07.002.

Sakata N, Takeuchi K, Noda K, Saku K, Tachikawa Y, Tashiro T et al. Calcification of the medial layer of the internal thoracic artery in diabetic patients: relevance of glycoxidation. J Vasc Res. 2003;40(6):567–74.

Giacco F, Brownlee M. Oxidative stress and diabetic complications. Circ Res. 2010;107(9):1058–70. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223545.

Lapolla A, Piarulli F, Sartore G, Ceriello A, Ragazzi E, Reitano R et al. Advanced glycation end products and antioxidant status in type 2 diabetic patients with and without peripheral artery disease. Diabetes Care. 2007:30(3):670–6.

Rabbani N, Thornalley PJ. Methylglyoxal, glyoxalase 1 and the dicarbonyl proteome. Amino Acids. 2012;42(4):1133–42. doi:10.1007/s00726-010-0783-0.

Lapolla A, Flamini R, Lupo A, Arico NC, Rugiu C, Reitano R et al. Evaluation of glyoxal and methylglyoxal levels in uremic patients under peritoneal dialysis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1043:217–24.

Shiu SW, Tan KC, Wong Y, Leng L, Bucala R. Glycoxidized LDL increases lectin-like oxidized low density lipoprotein receptor-1 in diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203(2):522–7. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.07.012.

Hanssen NM, Wouters K, Huijberts MS, Gijbels MJ, Sluimer JC, Scheijen JL et al. Higher levels of advanced glycation endproducts in human carotid atherosclerotic plaques are associated with a rupture-prone phenotype. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(17):1137–46. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht402.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

About this article

Cite this article

Ito, K., Sakata, N., Nagai, R. et al. High serum level of methylglyoxal-derived AGE, Nδ-(5-hydro-5-methyl-4-imidazolone-2-yl)-ornithine, independently relates to renal dysfunction. Clin Exp Nephrol 21, 398–406 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-016-1301-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-016-1301-9