Abstract

Background

Patients with advanced gastric cancer (AGC) are often treated with irinotecan monotherapy as salvage-line therapy. However, the survival benefit of this therapy remains to be elucidated.

Methods

Medical records of AGC patients who were treated with irinotecan monotherapy as salvage-line treatment in six institutions from 2007 to 2014 were reviewed.

Results

A total of 146 patients had prior fluoropyrimidine and taxane therapies, and 75.3% had prior platinum therapy. The median age was 66 (range 27–81) years, and 102 males (69.9%) were included. Performance status (PS) was 0/1/2/3 in 53/70/19/4 patients. Eighty-nine patients (61.0%) had two or more metastatic sites. Irinotecan monotherapy as 3rd-/4th-line therapy was performed in 135/11 (92.5%/7.5%). The median number of administrations was 4 (range 1–62). Forty-six patients (31.5%) required initial dose reduction at the physician’s discretion. The overall response rate was 6.8%, and the disease control rate was 43.1%. The median PFS was 3.19 months [95% confidence interval (CI) 2.30–4.08 months], and the median OS was 6.61 months (95% CI 5.94–7.28 months). Grade 3/4 adverse events were hematological toxicity (46 patients, 31.5%) and non-hematological toxicity (50 patients, 34.2%). Hospitalization due to adverse events was required in 31 patients (21.2%). Patients with relative dose intensity (RDI) less than 80% showed similar survival to those with RDI 80% or higher.

Conclusions

Irinotecan monotherapy was relatively safely performed as salvage-line treatment for AGC in Japanese clinical practice. Careful patient selection and intensive modification of the dose of irinotecan might possibly be associated with favorable survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common malignancy in the world and the third leading cause of cancer death in both sexes worldwide [1]. Systemic chemotherapy has been performed for advanced gastric cancer (AGC). Although recent developments of anti-tumor agents for AGC have improved therapeutic outcomes, the main purpose of the therapy is still palliation [2]. Thus, more effective therapeutic strategies are needed.

The standard initial chemotherapy for AGC is combination chemotherapy involving fluoropyrimidine and platinum, which achieved median progression-free survival (PFS) of 6 months and median overall survival (OS) of 11 months [3,4,5,6]. HER2-positive AGC patients are treated with the above doublet chemotherapy plus trastuzumab, and median OS has been reported to be 13 months [7]. In second-line chemotherapy, monotherapy with paclitaxel, docetaxel, irinotecan, or ramucirumab has shown survival benefits compared to best supportive care in prospective phase III clinical studies [8,9,10,11]. Since a recent study showed significant extension of OS of AGC patients with second-line chemotherapy, combination therapy with paclitaxel and ramucirumab is recognized as a standard therapy [12].

Irinotecan, a topoisomerase I inhibitor, has long been known to be effective in AGC [13]. Whereas gastrointestinal and hematological toxicities often appeared in treatment with irinotecan, they are generally manageable when appropriate patients are chosen. A randomized phase III study examining the survival benefit of irinotecan monotherapy compared with paclitaxel monotherapy, which has been thought to be the standard regimen in Japan, as second-line chemotherapy of AGC was reported [14]. This study showed almost equivalent overall survival for irinotecan and paclitaxel. Interestingly, 75.0% of the patient group treated with paclitaxel in this study received irinotecan-containing chemotherapy as third-line treatment, and 87.0% of the paclitaxel group patients received irinotecan as later-line treatment. These findings imply the wide use of irinotecan for AGC after second-line paclitaxel in Japanese clinical practice. Shitara and colleagues showed that AGC patients who had a series of chemotherapy containing three drugs, fluoropyrimidine, taxanes, and irinotecan, had longer survival times, suggesting the clinical significance of salvage-line treatment after second-line CT [15].

Recently, a retrospective study of irinotecan monotherapy as third-line chemotherapy in a single institution was reported [16]. This study showed favorable PFS and OS, suggesting the efficacy of this therapy, while several toxicities, including fatigue and anemia, were noted, suggesting the need for appropriate patient selection and careful dose modification. However, no prospective clinical studies of the efficacy of chemotherapy after second-line treatment have been performed. Thus, the superiority of third- or later-line chemotherapy to best supportive care has not been clarified. Additionally, actual dose and schedule modifications to fit these heavily treated AGC patients are still unclear, though the aforementioned study used a bi-weekly administration regimen of irinotecan 150 mg/m2. Irinotecan has also been given as fourth-line chemotherapy in the clinical situation [14].

The present study examined the efficacy and safety of irinotecan monotherapy in third- or later-line treatment in multiple institutions with a greater number of patients than previous studies. Furthermore, the impact of modifications of irinotecan monotherapy according to patient characteristics and risk factors on efficacy and safety was also analyzed.

Patients and methods

Patients

AGC cases treated with irinotecan monotherapy as third- or fourth-line therapy in the period from 1 January 2007 to 31 December 2014 in six institutions of the Kyushu Medical Oncology Group were registered and retrospectively examined. The eligibility criteria were 20 years or older, histologically proven adenocarcinoma of the stomach or the esophagogastric junction, measurable or evaluable lesions according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1, preserved Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), no major organ dysfunction, no active multiple primary cancers, and being refractory or intolerant to fluoropyrimidine and taxanes. The expression status of the HER2 molecule on the tumor cells was not considered. This study was approved by the ethics committees of JCHO Kyushu Hospital and the other participating institutions according to the guidelines for biomedical research specified in the Declaration of Helsinki. Because of the retrospective nature of the present study, informed consent was not obtained from each patient.

Clinical variables assessed

Information for each patient was retrospectively evaluated using electronic medical records. Items surveyed in this study included age, sex, ECOG PS, body surface area, comorbidities, histopathological diagnosis by the Lauren classification, tumor cell HER2 expression, metastatic and recurrent sites, and tumor status. Information about previous treatments including surgery and systemic chemotherapy was evaluated. Information about the study chemotherapy included the administration doses of chemotherapy, best response, PFS, OS, and reasons for chemotherapy termination. Therapy-related toxicities were assessed according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTC-AE) version 4.0.

Treatments

All patients were treated with irinotecan monotherapy as third- or fourth-line treatment. Irinotecan at a dose of 150 mg/m2 was administered intravenously every 2 weeks. As antiemetic prophylaxis, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone were given 30 min before the administration of irinotecan. The initial dose was reduced at the discretion of the investigator. The treatment was continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or the decision to discontinue by the patient or the investigator. The dose was reduced in cases of adverse events, or administration was suspended until recovery from the adverse events.

Subgroup analyses based on relative dose intensity and the initial dose of irinotecan

Subgroup analyses of the patients based on relative dose intensity (RDI) and the initial dose of irinotecan were performed. Patients with RDI of 80% or higher were defined as the RDI-high group, and patients with RDI of less than 80% were defined as the RDI-low group. In another subgroup analysis, patients were separated into two groups: patients treated with an initial dose of irinotecan of 150 mg/m2 (the high-initial dose group) and those with an initial dose of 120 mg/m2 or less (the low-initial dose group).

Statistical analysis

PFS was defined as the period from the initiation of the irinotecan monotherapy to the day of tumor progression determined by each institution or death from any cause. OS was defined as the period from initiation of chemotherapy to the day of death from any cause. PFS and OS were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to compare survival of the two patient groups. Analyses were carried out with a two-sided alpha type I error of 5%. All statistical procedures were performed using SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Patients’ characteristics

A total of 146 AGC patients who were treated with irinotecan monotherapy as third- or fourth-line treatment were examined (Table 1). The median age of the patients was 66 years (range 27–81 years). Forty-four females and 102 males were included. The number of patients with PS 0/1/2/3 was 53/70/19/4. Histologically, 86 (58.9%) patients were diagnosed with diffuse-type adenocarcinoma, and 41 patients (28.1%) were diagnosed with intestinal-type adenocarcinoma. Seventeen patients’ (11.6%) tumors were HER2-positive. Eighty-eight patients (60.3%) harbored a target lesion, and 70 (47.9%) had peritoneal metastases. Forty-nine patients had undergone a gastrectomy.

In terms of the prior chemotherapies, a fluoropyrimidine plus platinum combination and fluoropyrimidine monotherapy were administered in 101 (69.2%) and 43 (29.4%) patients, respectively, as first-line treatment. As second-line treatment, taxanes were given to 134 (91.1%) patients. Eleven of the patients (7.5%) were treated with taxanes as third-line treatment. Anti-HER2 therapy with trastuzumab was performed in 14 (9.6%) patients. Anti-VEGFR therapy with ramucirumab was performed in three (2.1%) patients. Some patients suffered from comorbidities including hypertension (27, 18.5%), cardiovascular disease (18, 12.3%), and diabetes mellitus (15, 11.3%). The median time from first-line chemotherapy to irinotecan administration was 10.9 months (range 3.0–73.0 months), and the median first-line PFS was 5.8 months (range 1.2–59.1 months). The overall response rate in 88 assessable patients was 30.4%, including 5 complete responses and 36 partial responses.

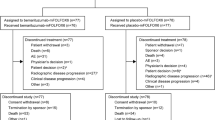

Treatments

The median number of administrations of irinotecan monotherapy as third- or fourth-line treatment was 4 (range 1–62) (Table 2). While 100 (68.5%) patients started irinotecan monotherapy at a dose of 150 mg/m2, 46 (31.5%) patients started at a reduced dose of irinotecan (less than 120 mg/m2). Among the 100 patients who started at 150 mg/m2 of irinotecan, dose reduction after the initial administration of irinotecan was required in 35 patients.

The relative dose intensity (RDI) of irinotecan was 74.6% in the overall patient group. Sixty-seven patients (45.9%) were exposed to irinotecan at an RDI of 80% or more. The therapies were continued until disease progression in 120 patients (82.2%), intolerable adverse events in 6 patients (4.1%), decreased PS in 9 patients (6.2%), and patient’s refusal in 8 patients (5.5%). No treatment-related deaths were observed. In terms of the subsequent therapies, best supportive care was performed in 98 patients (67.1%), and chemotherapies were given in 48 patients (32.9%) including taxanes in 19 (39.6%), methotrexate plus 5-FU in 15 (31.2%), platinum in 5 (10.4%), and others in 9 (18.8%).

Efficacy

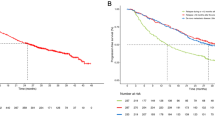

Overall response was evaluated in 88 patients with measurable lesions (Table 3). Partial response (PR) was observed in 6 patients (6.8%), and stable disease (SD) was observed in 32 patients (36.4%). The disease control rate (CR + PR + SD) was 43.2%, the median PFS was 3.2 months [95% confidence interval (CI) 2.3–4.1 months], and the median OS was 6.6 months (95% CI 5.9–7.3 months) (Fig. 1a,b).

Kaplan-Meier plots for progression-free (PFS) and overall (OS) patient survival. PFS (a) and OS (b) curves for all AGC patients treated with the irinotecan monotherapy in this study; PFS (c) and OS (d) curves for patients treated with irinotecan monotherapy according to relative dose intensity (RDI). Solid lines indicate the RDI-low group (RDI less than 80%), and the dotted lines indicate the RDI-high group (RDI of 80% or higher); PFS (e) and OS (f) curves for patients treated with irinotecan monotherapy according to the dose of initial therapy. Solid lines indicate the high-initial dose group (initial dose of irinotecan of 150 mg/m2), and dotted lines indicate the low-initial dose group (initial dose of irinotecan of 120 mg/m2 or less)

Safety

Neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia of any grade were observed in 43.2, 81.5, and 10.3% of patients overall, respectively (Table 4). Grade 3 or 4 neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia appeared in 19.2, 19.2, and 1.4%, respectively, and any of grade 3 or 4 hematological toxicity appeared in 46 patients (31.5%). In terms of non-hematological toxicity, any grade nausea (44.5%), anorexia (62.3%), diarrhea (38.4%), and fatigue (56.8%) were frequently observed. The above non-hematological toxicities of grade 3 or 4 were seen in 4.1, 5.5, 2.1, and 6.8%, respectively, and any of grade 3 or 4 non-hematological toxicity appeared in 34.2%. Febrile neutropenia of grade 3 or 4 occurred in nine patients (6.2%).

Efficacy and safety analyses according to RDI and the initial dose of irinotecan

Since more than half of the total patient group had an RDI less than 80%, the efficacy and safety were compared between two groups, patients with RDI of 80% or higher (the RDI-high group; 67 patients, 45.9%) and patients with RDI of less than 80% (the RDI-low group; 79 patients, 54.1%) (Table 2). The median PFS of the RDI-high group and RDI-low group was 2.34 months (95% CI 2.10–2.63 months) and 3.72 months (95% CI 3.03–4.40 months), respectively (Fig. 1c). The median OS of each group was 6.41 months (95% CI 5.11–7.71 months) and 6.67 months (95% CI 5.30–8.05 months), respectively (Fig. 1d).

To examine the impact of initial dose reduction of irinotecan on efficacy and safety, efficacy and safety were also evaluated according to the initial dose of irinotecan. Patients treated with an initial dose of irinotecan of 150 mg/m2 (the high-initial dose group) and those with an initial dose of 120 mg/m2 or less (the low-initial dose group) included 100 (68.5%) and 46 patients (31.5%), respectively (Table 2). The median PFS of the high-initial dose group and the low-initial dose group was 3.06 months (95% CI 2.26–3.86 months) and 3.22 months (95% CI 1.50–4.94 months), respectively (Fig. 1e). The median OS of each group was 6.77 months (95% CI 5.77–7.78 months) and 5.56 months (95% CI 4.44–6.68 months), respectively (Fig. 1f).

Discussion

Although the appropriate dose and schedule to administer irinotecan as third- and later-line treatment have not been clarified, bi-weekly administration at a dose of 150 mg/m2 was relatively commonly used in the present study based on the previous phase III studies of second-line treatments [9, 14]. Though the present study cohort included heavily treated patients and patients with peritoneal dissemination, patients treated with irinotecan monotherapy had a median PFS of 3.19 months and a median OS of 6.1 months, which are equivalent to those in the previous clinical studies. The randomized phase III study demonstrated the survival benefit of nivolumab, human anti-programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) antibody, as third- or later-line treatment for AGC patients [17]. The median OS of the patients treated with nivolumab was significantly longer than that of best supportive care [5.32 versus 4.14 months, hazard ratio (HR) 0.63, 95% CI 0.50–0.78, p < 0.0001]. The median PFS was also significantly better in the nivolumab group than in the placebo group (1.61 versus 1.45 months, HR 0.60, 95% CI 0.49–0.75, p < 0.0001). Compared with this study, the present median OS and PFS were both longer than not only the results of the placebo group, but also the nivolumab group, suggesting that irinotecan monotherapy as third- and later-line treatment could contribute to prolonged survival of AGC patients.

In comparison with the previous studies of irinotecan monotherapy as second-line treatment, the present data showed comparable survival effects to those in second-line chemotherapies. In the WJOG4007G study, which was a phase III study that compared second-line treatment with weekly paclitaxel therapy versus irinotecan monotherapy, irinotecan showed a median OS of 8.4 months (95% CI 7.6–9.8 months) [18]. The other phase III study comparing chemotherapy with best supportive care in second-line treatment demonstrated that AGC patients treated with irinotecan monotherapy had a median OS of 6.5 months (95% CI 4.5–8.5 months) [9].

Recently, two retrospective analyses of irinotecan monotherapy as salvage-line treatment for AGC were reported. Kawakami et al. examined 50 patients in a single institution and reported a median PFS of 66 days and a median OS of 180 days [16]. Nishimura et al. reported that 52 AGC patients received third-line irinotecan monotherapy with a median PFS of 2.3 months and a median OS of 4.0 months [19]. These survival data were almost equivalent to the present results [16]. There were no apparent differences in the patients’ characteristics between these studies and the present study, except that irinotecan monotherapy was used as fourth-line treatment in 11 cases (7.5%) in the present study. While these two studies were each conducted in single institutions, the present cohort included more patients from multiple institutions and with more diversified backgrounds than the previous ones, possibly enabling generalization of the findings.

Irinotecan monotherapy as second-line chemotherapy in the WJOG4007G study showed a relatively higher ratio of patients with grade 3 or 4 adverse events than the present study, even though the median number of administration was almost equivalent (WJOG4007G versus the present study, 4.5 versus 4) [14]. However, it is necessary to be careful that adverse events tend to be reported to be less frequent in retrospective studies than prospective studies. Since the present study included patients with poorer conditions because of the later-line treatment than the WJOG4007G study, flexible dose modification and treatment schedule alteration might have been performed in the present study to continue irinotecan monotherapy even in the later-line.

The survival data of the patient groups were then further compared according to the RDI to assess the influences of dose and schedule modifications on efficacy and safety. The patients who had irinotecan monotherapy with an RDI of less than 80% (the RDI-low group) tended to suffer from grade 3 or 4 neutropenia, anemia, febrile neutropenia, and anorexia (Appendix Table 2). The frequent appearance of toxicities in the RDI-low group might require dose reduction and treatment delay. However, the RDI-low group had slightly better PFS and OS than the RDI-high group estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method (PFS; HR 1.476, 95% CI 1.055–2.064, p = 0.023, OS; HR 1.244, 95% CI 0.881–1.756, p = 0.22). Since there were no significant differences in patients’ background characteristics between the two groups, including PS, comorbidities, major organ dysfunctions, and efficacy of first-line treatment such as tumor response and PFS (Appendix Table 1), it might be difficult to clarify the reasons for the trend for better survival in the RDI-low group. One possible explanation is that the intensive dose modification and schedule alteration because of hematological toxicities enabled maintenance of tumor growth suppression and continuing irinotecan monotherapy. These observations suggest that a decrease of RDI according to the adverse events might not cause a serious decrease in the survival benefit of irinotecan monotherapy.

In this study, 31.5% of all patients were treated with an initially reduced dose of irinotecan. The previous retrospective study of third-line irinotecan monotherapy also reported that 26% of all patients required initial dose reduction [16]. To assess the impact of initial dose reduction on survival and the safety profile, patients treated with irinotecan at an initial dose of 150 mg/m2 (the high-initial dose group) were compared with those treated with ≤120 mg/m2 (the low-initial dose group). Importantly, the low-initial dose group tended to show more severe toxicities (Appendix Table 2), and equivalent survival results were observed in the two groups, while baseline patients’ characteristics and efficacy of prior treatment were almost similar between the two groups (Appendix Table 1). Thus, patients who have risk factors might be treated with an initially decreased dose of irinotecan and finally show equivalent survival benefit to those treated without initial dose reduction. Because of the retrospective nature of this study, the actual reason for the initial dose reduction in each patient was not available, but a general decision by investigators in clinical practice could result in appropriate therapeutic dose selection. These findings support appropriate dose reduction and schedule alterations of irinotecan monotherapy as being beneficial based on the general condition of the patients and the severity of previous adverse events. Additionally, although half of the present patients had peritoneal dissemination and ascites, which are considerable risk factors for adverse events caused by irinotecan therapy, treatments were safely performed in these patients, possibly because of the dose modifications.

The aforementioned phase III study proved the efficacy of nivolumab for salvage-line chemotherapy of AGC [17]. Among the nivolumab-treated patients in this study (n = 330), nivolumab was administered as fourth- or later-line treatment in 79.1% of the patients, and 74.8% of these nivolumab-treated patients were administered irinotecan prior to nivolumab. On the other hand, the rate of patients with subsequent administration of irinotecan after nivolumab was not reported. There has been no prospective study directly comparing the survival benefit of nivolumab with that of irinotecan in third-line treatment. Therefore, the preferential sequence of nivolumab and irinotecan as salvage-line chemotherapy for AGC patients who were resistant or intolerant to therapies by platinum, fluoropyrimidine, and taxane has not been conclusively determined. Further prospective studies are needed to clarify the appropriate sequence of chemotherapy.

The present study showed that irinotecan monotherapy as salvage-line treatment suggested a meaningful survival benefit and a relatively manageable toxicity profile for AGC patients in clinical practice. Although dose modification and schedule alteration of the therapy were intensively performed based on careful patient selection, survival equivalent to the clinical studies examining irinotecan monotherapy as second-line treatment for AGC was observed, suggesting that appropriate modification of the regimen is suitable for this patient population. To prove the efficacy of irinotecan monotherapy as salvage-line treatment for AGC and identify the most effective sequence of therapy with nivolumab, further prospective randomized clinical studies are warranted.

References

International Agency for Research on Cancer, WHO. GLOBOCAN 2012: estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.

Association Japanese Gastric Cancer. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver.4). Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:1–19.

Koizumi W, Narahara H, Hara T, Takagane A, Akiya T, Takagi M, et al. S-1 plus cisplatin versus S-1 alone for first-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer (SPIRITS trial): a phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:215–21.

Boku N, Yamamoto S, Fukuda H, Shirao K, Doi T, Sawaki A, et al. Fluorouracil versus combination of irinotecan plus cisplatin versus S-1 in metastatic gastric cancer: a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1063–9.

Kang YK, Kang WK, Shin DB, Chen J, Xiong J, Wang J, et al. Capecitabine/cisplatin versus 5-fluorouracil/cisplatin as first-line therapy in patients with advanced gastric cancer: a randomised phase III noninferiority trial. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:666–73.

Cunningham D, Starling N, Rao S, Iveson T, Nicolson M, Coxon F, et al. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin for advanced esophagogastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:36–46.

Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, Chung HC, Shen L, Sawaki A, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:687–97.

Thuss-Patience PC, Kretzschmar A, Bichev D, Deist T, Hinke A, Breithaupt K, et al. Survival advantage for irinotecan versus best supportive care as second-line chemotherapy in gastric cancer—a randomised phase III study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (AIO). Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2306–14.

Kang JH, Lee SI, Lim DH, Park KW, Oh SY, Kwon HC, et al. Salvage chemotherapy for pretreated gastric cancer: a randomized phase III trial comparing chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care alone. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1513–8.

Ford HE, Marshall A, Bridgewater JA, Janowitz T, Coxon FY, Wadsley J, et al. Docetaxel versus active symptom control for refractory oesophagogastric adenocarcinoma (COUGAR-02): an open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:78–86.

Fuchs CS, Tomasek J, Yong CJ, Dumitru F, Passalacqua R, Goswami C, et al. Ramucirumab monotherapy for previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (REGARD): an international, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:31–9.

Wilke H, Muro K, Van Cutsem E, Oh SC, Bodoky G, Shimada Y, et al. Ramucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (RAINBOW): a double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1224–35.

Rothenberg ML. CPT-11: an original spectrum of clinical activity. Semin Oncol. 1996;23:21–6.

Hironaka S, Ueda S, Yasui H, Nishina T, Tsuda M, Tsumura T, et al. Randomized, open-label, phase III study comparing irinotecan with paclitaxel in patients with advanced gastric cancer without severe peritoneal metastasis after failure of prior combination chemotherapy using fluoropyrimidine plus platinum: WJOG 4007 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4438–44.

Shitara K, Matsuo K, Mizota A, Kondo C, Nomura M, Takahari D, et al. Association of fluoropyrimidines, platinum agents, taxanes, and irinotecan in any line of chemotherapy with survival in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:155–60.

Kawakami T, Machida N, Yasui H, Kawahira M, Kawai S, Kito Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of irinotecan monotherapy as third-line treatment for advanced gastric cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;78:809–14.

Kang YK, Satoh T, Ryu MH, Chao Y, Kato K, Chung HC, et al. Nivolumab (ONO-4538/BMS-936558) as salvage treatment after second or later-line chemotherapy for advanced gastric or gastro-esophageal junction cancer (AGC): A double-blinded, randomized, phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 35, 2017 (suppl 4S; abstract 2).

Higuchi K, Tanabe S, Shimada K, Hosaka H, Sasaki E, Nakayama N, et al. Biweekly irinotecan plus cisplatin versus irinotecan alone as second-line treatment for advanced gastric cancer: a randomised phase III trial (TCOG GI-0801/BIRIP trial). Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:1437–45.

Nishimura T, Iwasa S, Nagashima K, Okita N, Takashima A, Honma Y, et al. Irinotecan monotherapy as third-line treatment for advanced gastric cancer refractory to fluoropyrimidines, platinum, and taxanes. Gastric Cancer. 2016 [Epub ahead of print].

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients and their families for participating in this study and the medical staff for their respective contributions to the treatment of patients.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

K. Akashi and E. Baba have received a research Grant from Yakult Honsha Co., Ltd.

Research involving human participants

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions. Informed consent or substitute for it was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Makiyama, A., Arimizu, K., Hirano, G. et al. Irinotecan monotherapy as third-line or later treatment in advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 21, 464–472 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-017-0759-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-017-0759-9