Abstract

Primary productivity is in the foundation of farming communities. Therefore, much effort is invested in understanding the factors that influence the primary productivity potential of different soils. The International Long-Term Ecological Research (ILTER) is a network that enables valuable comparisons of data in understanding environmental change. In this study, we investigate three ILTER cropland sites and one long-term field experiment (LTE) outside of the ILTER network. The focus is on the influence of different management practices (tillage, crop residue incorporation, and compost amendments) on primary productivity. Data mining analyses of the experimental data were carried out in order to investigate trends in the productivity data. We generated predictive models that identify the influential factors that govern primary productivity. The data mining models achieved very high predictive performance (r > 0.80) for each of the sites. Preceding crop and crop of the current year were crucial for primary productivity in the tillage LTE and compost LTE, respectively. For both crop residue incorporation LTEs, plant-available Mg affected productivity the most, followed by properties such as soil pH, SOM, and the crop residue management. The results obtained by data mining are in line with previous studies and enhance our knowledge about the driving forces of primary productivity in arable systems. Hence, the models are considered very suitable and reliable for predicting the primary productivity at these ILTER sites in the future. They may also encourage researcher-farmer-advisor-stakeholder interaction, and thus create enabling environment for cooperation for further research around these ILTER sites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Primary productivity, the capacity of a soil to produce plant biomass for human use (as food, feed, fuel, or fiber), is one of the cornerstones of prosperous farming communities. Accordingly, farmers need to focus on multiple soil functions in order to maintain the productivity function of the soil (Schulte et al. 2014) and to help secure the viability of farms for the next generations. This includes the soils’ provision of clean drinking water, the recycling of nutrients, carbon sequestration, and soil serving as a habitat for biota (Schulte et al. 2015). To this end, several improved management practices are being applied in the field. No-tillage or non-inversion tillage practices are being promoted to reduce the labor and crop production costs, but also due to their positive effects on soil organic matter (SOM) and soil aggregate stability (Bauer et al. 2015; Tatzber et al. 2008; Spiegel et al. 2007). Incorporation of crop residues and various organic fertilizer amendments, such as composts and farmyard manure, is feasible options for substituting mineral nitrogen fertilizers (Spiegel et al. 2010). Currently, conservation agriculture is becoming more wide-spread among the global farming community. Already approximately 125 million hectares of land are managed by the principles of conservation agriculture (Friedrich et al., 2012; Brouder and Gomez-Macpherson, 2014). The definition of conservation agriculture includes minimum, non-inversion or reduced tillage, combined with retention of crop residues on the soil surface and crop rotation. The aim is to conserve soil and water for optimum productivity (Hobbs et al. 2008; Kertész and Madarász 2014).

The International Long-Term Ecological Research (ILTER) represents a network that enables valuable comparisons of data for understanding environmental change. Nonetheless, cropland sites are still underrepresented in the network, and more sites would be needed for global comparisons. In Austria, only four agricultural ILTER sites are included in the network of 38 sites in total (Mirtl et al. 2015). This study focuses on three of the cropland sites (tillage and crop residue incorporation), as well as one long-term field experiment (compost amendments) outside of the ILTER network.

The previous investigations of the selected LTER sites have focused on how the different improved management practices, i.e., tillage (Franko and Spiegel 2016; Tatzber et al. 2008; Spiegel et al. 2007), crop residue incorporation (Spiegel et al. 2018), cropping systems (Tatzber et al. 2009, 2012, 2015a, b; Tatzber 2009), and organic/compost amendments (Lehtinen et al. 2017; Hijbeek et al. 2017; Körschens et al. 2013), affected the soil properties as well as soil productivity. However, no analyses of the experimental data have been carried out in order to determine patterns in the productivity data.

There are many positive examples of using data mining techniques for building predictive models in the field of agricultural and environmental sciences (Bondi et al. 2018; Bui et al. 2009; Debeljak et al. 2007, 2008; Goldstein et al. 2017; Kuzmanovski et al. 2015; Shekoofa et al. 2014; Trajanov 2011). Their biggest advantage is that they are applied on easily obtainable empirical data, and the parametrization of the data mining models is done automatically from the data; hence it is not influenced by the subjectivity of the modelers. By applying data mining methods, data sets from long-term field experiments can be turned into an understandable structure, and interpretable patterns (i.e., long-term trends and their drivers) in the data can be identified.

Data mining, as a part of the Knowledge Discovery in Databases (KDD) process, uses machine learning and statistical methods in order to find interesting patterns in data (Fayyad et al. 1996). The goal of data mining is to extract information from datasets that is intelligible and useful in an understandable and easily interpretable format. Different data mining algorithms are used to address different data mining tasks and discover different patterns in the data (e.g., decision trees, clusters, equations, rules). These algorithms search through the space of patterns (models) to find interesting patterns that are valid in the given data.

This study was designed to predict primary productivity and to identify the driving factors that govern primary productivity by means of data mining. To this end, we addressed the following questions within the framework of the selected field experiments:

-

(1)

Can data mining help make reliable predictive models of primary productivity from LTE (long-term field experiments) data?

-

(1)

What are the driving factors of primary productivity in the selected arable LTEs that are sufficiently fertilized with main nutrients?

-

(2)

Do the selected management practices influence primary productivity?

Materials and methods

International Long-Term Ecological Research (ILTER) experimental sites

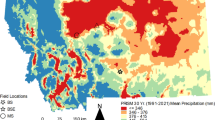

This paper investigated data from four Austrian long-term field experiments (LTEs, Fig. 1).

Tillage

The long-term field experiment investigating different tillage management (tillage LTE) was established in Fuchsenbigl (Table 1). In brief, the experiment included three different tillage systems (minimum, reduced, and conventional tillage) (Spiegel et al. 2002, 2007; Tatzber et al. 2008). The experiment consisted of a randomized block design, the plots measuring 60 m × 12 m each. The crop rotation was not fixed and consisted of the most important crops for the region such as cereals, sugar beet, maize, and grain legumes.

Crop residue incorporation

Two long-term field experiments were established to investigate the management of crop residues, crop residue LTE in Rutzendorf, and crop residue LTE in Grabenegg. Both sites have recently been described by Spiegel et al. (2018). The field experiments consisted of a randomized block design with four replicates, each plot measuring 32 m × 6 m (192 m2) in Rutzendorf and 30 m × 7.5 m (225 m2) in Grabenegg. There were four P-fertilization stages (0, 33, 66, 131 kg P ha-1y-1), and all crop residues were either incorporated or removed in the treatments. The crop rotation was not fixed and consisted of the most important crops for both regions, such as cereals, sugar beet, grain maize, and grain legumes.

Compost amendments

The long-term compost LTE was designed in Ritzlhof near Linz, Upper Austria, to study the effects of different compost amendments on chemical, physical, and microbial soil parameters and plants. The compost LTE and its soils have previously been described in Lehtinen et al. (2017) and references therein. The field experiment consists of a randomized block design with four replicates, the plots measuring 5 m × 6 m (= 30 m2). The field trial includes a control plot (zero N), minerally fertilized plots (40 kg N, 80 kg N, 120 kg N ha−1 y−1) and biowaste compost, green waste compost, manure compost, and sewage sludge compost plots (each treatment corresponding to 175 kg N ha−1) with a crop rotation of winter wheat, winter barley, maize, and pea (without compost application). In further variants, the four compost amendments are fertilized with 80 kg mineral N (NH4NO3) ha−1.

Data mining methods

In our study, we used data mining algorithms for generation of decision trees (Breiman et al. 1984), in particular model and regression trees. The algorithms for building decision trees are one of the most commonly used data mining algorithms. They predict the value of a dependent variable (termed target attribute) from a set of independent variables (attributes). They are hierarchical models that contain internal and terminal nodes, connected with edges. In each inner node, the value of an attribute is tested and compared to a constant value. The edges coming out from the node correspond to the outcome of the test. The leaf nodes contain the predictions of the target attribute that apply to all samples that fall in that leaf. To predict the value of the target attribute for a new sample, it is routed down the tree according to the values of the attributes that are tested in each node. When the sample reaches a leaf, it is given the prediction assigned to the leaf.

When the values of the target attribute are numeric, the leaves of the tree contain models for predicting it. The models can be piece-wise linear regression equations, in which case the decision trees are known as model trees, or can be constant values and in this case, the decision trees are termed regression trees. When generating regression trees, syntactic constraints can also be used (Džeroski et al. 2010). The syntactic constraints influence the process of building the trees by defining a partial structure of the tree, from which point on the tree is generated automatically, following the regular regression tree algorithm.

In this study, we generated model and regression trees for each of the LTE experimental sites (tillage LTE, crop residue LTEs, and compost LTE). For easier interpretation of the model trees, we calculated the average predicted value of the samples that fall into each leaf according to its piece-wise equation, as well as their average actual values. When interpreting decision (classification or regression) trees, we start from the top (root) of the tree. The most important factors that influence the target attribute (primary productivity in our case) appear at the top. The importance of the attributes decreases as you move towards the lower levels of the tree.

There are different measures of predictive performance to assess how good the data mining models describe our data. To assess the performance of regression and model trees, we used the correlation coefficient as a measure: it quantifies the statistical correlation between the predicted and the real values of the target attribute. The values of the correlation coefficient can vary between 1 (perfect correlation) and − 1 (perfect negative correlation) through 0 (no correlation at all). In addition, to assess how good the model performs on new (test) data, we used the tenfold cross-validation technique (Witten and Frank 2011). In cross-validation, the dataset is split into n approximately equal partitions (folds). Each fold is (in turn) used for testing, while the remaining folds are used for training (building) the model. This procedure is repeated n times and, at the end, the correlation coefficients obtained in the different iterations are averaged to obtain the overall correlation coefficient of the data mining model. A common practice when generating data mining models is to use tenfold cross-validation as a standard method for their evaluation.

Another measure of predictive performance is Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) (Witten and Frank 2011). It is a measure that reports the average magnitude of the error. It is the square root of the average of squared differences between prediction and actual values of the target attribute.

To model the influence of different agricultural management techniques on primary productivity, we used the data mining package WEKA (Witten and Frank 2011), which implements a large collection of machine learning algorithms for different data mining tasks. In this study, we used the model and regression tree algorithm M5P. For generating regression trees with syntactic constraints, we used the decision and rule induction system CLUS (Blockeel and Struyf 2002).

Data description

The data from the four Austrian long-term field experiments, described in the “International Long-Term Ecological Research (ILTER) experimental sites” section, were organized and preprocessed in order to be analyzed using data mining techniques. The data comprising the three LTEs datasets are presented in Table 2. The attributes included the long-term monitoring data available from each of the experiments; thus, the attributes differed slightly between the LTEs.

Although the general structure of all datasets was similar, each dataset was preprocessed in a unique way in order to correctly address the goal and obtain the most accurate and interpretable data mining models possible. The structure of the separate datasets from each experimental site is explained in the following sections.

Tillage

The tillage dataset consisted of data from 18 years of experiments (1998–2015), yielding 162 samples, described with soil parameters, management techniques (tillage), and crop yields. In addition to these original attributes, for each example, we included the soil properties of the preceding year (derived attributes) in order to check whether the soil properties of the preceding year and the type of tillage applied on the field influence the crop yield in the current year.

Three types of crops were grown at the tillage experimental site: sugar beet, grain maize, and cereals. These crops have significantly different absolute yields. Therefore, we divided the dataset into three subsets, according to crop classes:

-

Sugar beet (number of samples 18)

-

Grain maize (number of samples 36)

-

Cereals: winter wheat, spring wheat, soybean, winter barley, spring barley (number of samples 108)

For the data mining analyses, we generated five scenarios using different combinations of original and derived attributes:

-

Scenario 1: Original attributes WITHOUT CEC and C/N

-

Scenario 2: Original attributes WITH CEC and C/N (excluding the attributes from which CEC and C/N are calculated)

-

Scenario 3: Original and derived attributes WITHOUT CEC and C/N

-

Scenario 4: Original and derived attributes WITH CEC and C/N (excluding the attributes from which CEC and C/N are calculated)

-

Scenario 5: Original and derived attributes WITH CEC and C/N and syntactic constraints (forcing the tillage attribute at the top of the decision trees)

The attributes from which CEC and C/N are calculated were excluded in scenarios 2 and 4 in order to avoid correlations in the investigated attributes.

Crop residue incorporation

The data from the crop residue incorporation experimental sites consisted of data from two LTEs—Rutzendorf and Grabenegg. Each dataset comprised 5 years of experiments (2002, 2008, 2010, 2012, and 2014), yielding 160 samples, described by soil properties, management practices (crop residue incorporation or removal), and the crop yield. Data about preceding years were not included in these datasets because the data in these LTEs were not collected for consecutive years. At these experimental sites, only cereal crops were grown, so there was no need to divide the datasets according to crop type.

Here, we performed two scenarios for both Rutzendorf and Grabenegg datasets:

-

Scenario 1: Using total nitrogen and total soil organic carbon attributes and excluding the C/N attribute

-

Scenario 2: Using C/N and excluding the total nitrogen and total soil organic carbon attributes

Compost amendments

The compost amendment dataset consisted of 8 years of experiments (1998, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2005, 2007, 2012, and 2015), yielding 384 samples, described by soil properties, management practices (type of fertilization and compost amendment), and crop yield. At this experimental site, two classes of crops were grown: maize and cereals (spring wheat, winter wheat, winter barley, and pea). As in the case of the tillage LTE data and to avoid biasing the data mining models, we divided the dataset into two subsets because the two types of crops have significantly different absolute crop yields in kg/ha: one consisting of data only for maize (144 examples) and the other for cereals (240 examples). Data on preceding crops grown on the fields were also included in the datasets.

Here, we also carried out two scenarios:

-

Scenario 1: Using total nitrogen and total soil organic carbon attributes and excluding the C/N attribute

-

Scenario 2: Using C/N and excluding the total nitrogen and total soil organic carbon attributes

Results

Tillage

The results of the obtained model and regression trees for the tillage experimental site are presented in Table 3 in terms of correlation coefficients (r) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE).

Figure 2 indicates that the preceding crop was of pivotal importance for primary productivity. The predictive performance of the models obtained for sugar beet was low. However, due to the low number of samples (18 in total) in this dataset, these results are unreliable. The best results (models) were obtained for grain maize and cereals, where the highest correlation coefficients (0.83 and 0.84, respectively) were obtained for scenario 4. Overall, the correlation coefficients of the models for grain maize and cereals were higher in scenarios 3 and 4, where we used soil and crop data of the preceding year, compared to the scenarios 1 and 2, where we used data only for the current year.

Crop residue incorporation

The regression trees of both trials highlight that the most important attribute for primary productivity in the crop residue incorporation long-term experiments was the plant-available Mg (Fig. 3).

For modeling the influence of soil and crop properties as well as crop residue incorporation on primary productivity, we had one dataset for each LTE, for which we carried out two scenarios. The predictive performances of the model and regression trees obtained for the two datasets and for both scenarios are very high (Table 4). This makes them very reliable for predicting and modeling the primary productivity in a field.

The best models were obtained for scenario 1. The regression trees for Grabenegg and Rutzendorf are presented in Fig. 3.

Compost amendments

The regression tree for modeling the primary productivity in cereals (Fig. 4) shows that in the compost amendment LTE, the crop grown on the field and the treatment applied on the field were the major drivers of primary productivity.

As in the crop residue LTE analyses, for the compost amendments experimental site, we developed models for two scenarios, using the C/N ratio and using total soil organic carbon and total nitrogen as separate attributes. The predictive performances of the obtained models are presented in Table 5.

The correlation coefficients of the models for both types of crops were very high, 0.78 and 0.94, respectively. The models obtained for the cereals dataset have especially high correlation coefficients, which make the predictions very reliable. The regression tree obtained for the cereals dataset is presented in Fig. 4.

Discussion

Tillage

In the tillage LTE, the crop rotation mimicked the current management practices in the area, i.e., the most common agricultural crops were grown in 3–6-year crop rotations. Various aspects influence a farmer’s decision which crop to grow, all of which may act at a local, regional, or even at the global scale (Hazell and Wood 2008). They may include the farm type, the economic market, the technological opportunities at hand, the possibilities for government or EU subsidies, as well as the nature of the farmer’s soil (Hazell and Wood 2008; Bennett et al. 2012). If economic market trends influence the choice of a crop of the season, the expected yields are probably one of the most important driving factors for the choice. Our data mining models clearly showed (Fig. 2) that cereal yields were significantly lower when sugar beet or winter wheat was the preceding crop compared to e.g., soybean or spring wheat. These differences may reflect a combination of factors, including how the grown crops influence the soil-plant interphase with regard to soil properties, pests, pathogens and soil microorganisms (Bennett et al. 2012), and residual effects on the succeeding crops—just to mention a fraction of the possibilities.

The importance of the preceding soil and crop properties is also evident from the generated model and regression trees. The best model tree, obtained for the cereals dataset and scenario 4 (Fig. 2), shows that the most important attributes for predicting yield were the preceding crop, the preceding yield, the C/N ratio, and the preceding CEC and plant-available phosphorus. These soil parameters are well-known to affect plant nutrition. A smaller C/N ratio indicates more rapid decomposition of soil organic matter and, thus, release of plant-available mineral nitrogen (Jarvis et al. 2011). The sum of exchangeable cations—in alkaline soils mainly Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+ and K+, which are adsorbed on the exchange complex of the soil—also indicate the nutritional status of the soil and may inform about deficiencies (Kopittke and Menzies 2007). Phosphorus is a key nutrient and essential for optimizing yields. Spiegel (2001) showed in another long-term experiment at the same site that plant-available P was significantly positively correlated with spring barley, sugar beet, and winter wheat yields. Thus, the model results are in line with earlier findings that yields were enhanced if CEC and plant-available phosphorus showed higher values.

We were also interested in determining how the management practice, in this case soil tillage, influences primary productivity. However, the attributes describing the management practice did not appear in the model and regression trees in scenarios 1 to 4. Thus, in scenario 5, we generated regression trees with syntactic constraints. Here, we defined the partial structure of the tree (syntactic constraint) in a way that we “forced” the management attributes to be at the top of the tree and from there, the tree was generated automatically from the data. Nonetheless, the correlation coefficients of these regression trees were lower than in scenarios 3 and 4. We therefore conclude that soil tillage, as a management practice, is less important for primary productivity than the current and preceding soil and crop properties. This is in line with former findings from this field experiment that, on average, yields did not differ between the investigated tillage practices (Franko and Spiegel 2016; Spiegel et al. 2002, 2010).

Crop residue incorporation

Gerendás and Führs (2013) recently reviewed the literature on the effect of magnesium on crop quality. Their review on cereals agrees with our results of positive yield response to plant-available Mg in the crop residue incorporation experiments in Rutzendorf and Grabenegg. Gerendás and Führs (2013), however, also show that there is not necessarily any quality response to Mg beyond the yield maximum. The magnesium available for plants depends on several factors including soil pH, soil moisture, weathering, and microbial activity of the soil (Senbayram et al. 2015). Grzebisz (2013) described the so-called “magnesium-induced nitrogen uptake” which highlights the positive effect of magnesium on the nitrogen uptake efficiency of the plants. Many factors, among them source rock material and its properties and grade of weathering as well as management practices such as crop rotation and fertilization practices, influence the availability of Mg to plants (Gransee and Führs 2013). In our study, it was plant-available Mg in the soils, not Mg fertilization, that was investigated and most important for crop yields. All the treatments in Grabenegg and Rutzendorf were sufficiently supplied with N, P, and K. This may explain why plant-available Mg became so important in our model (Gransee and Führs 2013). Magnesium is an essential plant nutrient that is one of the building blocks of chlorophyll (Gerendás and Führs 2013). Magnesium is also involved in enzyme activation, ATP formation and utilization, and growth of roots as well as in seed formation (Cakmak 2013), making it very important for the whole life cycle of a plant. In intensively farmed soils, such as soils of our two long-term field experiments, Mg balances become even more important for crop yields due to a possible rapid depletion of Mg of the soils (Cakmak 2013). Moreover, wheat grown under low Mg supply may be more prone to challenges due to severe environmental conditions such as heat (Cakmak 2013).

Besides Mg, also the pH value of the soil, SOC, and potential N mineralization (only in Grabenegg)—but also the crop residue management and the crop type (only Rutzendorf)—affected primary productivity. In the Grabenegg LTE, soils with slightly acidic pH values had higher crop yields than soils with lower acidity. In contrast, at Rutzendorf LTE, higher yields were achieved at alkaline soil pH levels. In both experiments, with higher soil pH, crop residue management influenced crop yields. Yields increased with long-term incorporation of crop residues. SOC was very different in the two experiments: low in Grabenegg and high in Rutzendorf. In Grabenegg, higher SOC led to higher yields, whereas this was not the case in the already highly supplied Rutzendorf soils. This is in line with results from 20 long-term field experiments in Germany (Körschens et al. 2013), where the relevance of initial SOC was emphasized. Both pH and SOC are fundamental for soil fertility, especially for the biological activity of soils (Diepenbrock et al. 2009), driving important biogeochemical cycles (e.g., C, N, and P). Former studies have also revealed that long-term crop residue incorporation leads to higher SOC compared to the yearly removal (Lehtinen et al. 2014; Poeplau et al. 2015, 2017; Spiegel et al. 2018). Lehtinen et al. (2014) showed a significant increase in SOC when crop residues were incorporated, but did not find significant correlations between SOC and crop yields. A general 6% increase in yields following crop residue incorporation, as compared to crop residue removal, was observed. Poeplau et al. (2015, 2017) have shown similar increase ranges in SOC following crop residue incorporation in Sweden and Italy. The interplay between soil organic matter and attainable yields also puzzled Hijbeek et al. (2017), who investigated how different organic inputs affected crop yields. Their assumption was that increased soil organic matter leads to increased crop yields, but to their surprise, the increase was not statistically significant when 20 European long-term experiments were investigated together. They explained this by differences between experimental sites and the soil properties, as well as organic inputs used in the various experiments (Hijbeek et al. 2017).

Compost amendments

In general, pea and spring wheat achieved lower yields than winter wheat and winter barley (Diepenbrock et al. 2009), not least because of the shorter growing season. For the cereal crops, spring and winter wheat and winter barley, fertilization was an important driver for yields. No or low mineral fertilization and only compost amendments resulted in lower yields compared to sufficient mineral fertilization or a combination of compost and mineral fertilization. Pea, a legume, did not use the given fertilizer either in mineral or in organic form. Our modeling results coincide with the results of conventional statistical analyses of a similar data set obtained from this long-term compost experiment (Lehtinen et al. 2017). In farm management, caution should be exercised with short crop rotations or when focusing on only the most yielding crops. This is because the long-term maintained crop yields are more important from a sustainability point of view than maximum profit for a single cropping season. In addition, the essential micronutrients may be neglected from the fertilization schemes when only a few crops are being considered (Rashid and Ryan 2004). Production of only a few different crops may require less technical equipment at the farm (Bullock 1992), although the farmer may observe yield declines after several years (Bennett et al. 2012). The effects of fertilization on crop yields are known, and the effect of compost combined with mineral fertilizer was also shown by Lehtinen et al. (2017) from the same compost LTE. The current models confirm the previous results and show that compost amendment alone may be insufficient to match the yields reached with mineral fertilizer. This may reflect slow nutrient release from the composts (Amlinger et al. 2003; Alluvione et al. 2013), which is ca. 5–15% in the year of compost amendment and only 2–8% in the following years (Amlinger et al. 2003).

Applicability and scalability of the results

There are several advantages of using data mining methods over classical statistical methods. First, the analyses are not limited to only a few attributes or pair-wise comparisons for modeling a certain soil function, but all available data can be used. Using all the available data enables discovering interesting and new—often unexpected—patterns from the data (Buczko et al. 2018). This can provide new knowledge and insights about the problem at hand (De’ath and Fabricius 2000; Debeljak and Džeroski 2011; Jiawei et al. 2006; Veenadhari et al. 2011). Because of their ability to represent the relationships between the attributes in a visual way, the discovered patterns and knowledge about the problem can be easily interpreted. Therefore, the created decision trees could also be used to strengthen the researcher-farmer-advisor-stakeholder dialog and to foster co-creation of new research questions with high farmer relevance. From the top attributes from the decision trees, the farmers could disentangle what may be limiting their productivity and how to improve it.

The construction of data mining models (model or regression trees) proceeds automatically from the available data, minimizing the researchers’ subjectivity during the generation of the models. This means that the form of the models and the interactions among the variables are induced automatically from the data and not set by the experts. Since the models were generated from data, they can be easily validated using different validation techniques such as tenfold cross-validation, train-test sets, or leave-one-out validation (Witten and Frank 2011). The limitations are connected to availability of long-term data. In case data on the role of soil aggregation or soil microbiology in productivity is not available, their importance in producing biomass cannot be shown. This calls for extending the attributes that are being monitored in LTEs.

The data mining models are predictive models; therefore, the validated models that achieve high predictive performance can be used to predict future scenarios of the same type and under similar conditions as the ones that were used for constructing the models. Finally, the data mining models are usually presented in a form, such as a decision tree, which is intuitive and easy to interpret by the researchers.

The data mining models generated in this study achieved better predictive performance for each of the LTEs than the statistical studies previously carried out on the same data (Spiegel et al. 2002, 2007, 2018; Lehtinen et al. 2017). They are therefore very suitable and reliable for predicting the primary productivity at the experimental sites in the future. A great advantage of using data mining methodology over classical statistical or mechanistic models is the simple and fast construction of models that can be easily adapted to new data. Accordingly, having an established data collection system at the LTE sites would simplify upscaling the predictive data mining models to newest data. Having more data from these sites will make the models more general and might further improve the predictive performances. Collecting data on a regional basis and covering important farming regions would improve regional modeling efforts. The farmers could, for example, include their soil monitoring data into the models, in order to find more regional patterns. The created decision trees could support researcher-farmer-advisor dialog on productivity management. However, obtaining empirical data from additional experimental sites is most often a difficult and time-consuming task and presents a limiting factor when applying data mining technologies in the field of agronomy. Incomplete or inconsistent data can bias the data mining models, so the completeness and quality of the data is also an important factor in this approach.

Conclusions

Our study has generated primary production data mining models with high predictive performance for all four LTEs selected. The most important driving factors for productivity were preceding crop, plant-available Mg and crop of the growing year for tillage LTE, crop residue LTEs, and compost LTE, respectively. In addition, soil properties such as soil pH, SOC, C/N ratio, preceding CEC, and preceding plant-available P played a role. Crop residue incorporation as well as sufficient mineral fertilization or combined compost and mineral fertilizer treatments of the soils proved to be effective measures to optimize crop yields.

In this study, data mining techniques were used for the first time in these LTEs to discover knowledge and patterns from the data. While the model and regression trees generated in this study are region specific, the data mining approach enabled the effects of changing management and soil, along with soil fertility parameters over time, to be assessed in the context of crop yields and productivity at the sites. The knowledge obtained from our predictive models can be utilized by farmers in this region to predict how future management will affect the productivity of their soils. In a more general context, this methodology can be employed in other regions, where long-term data sets comprising a few critical but widely measured soil and crop parameters are available. This approach enables performing structural dynamic modeling, which is one of the main methodological goals in ecological modeling when dynamic, unpredictable systems are involved.

These results are also important in understanding the driving forces of primary productivity in arable systems that are sufficiently fertilized with main nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium). We can highlight which management practices positively influence crop yields. This calls for further investigations on other agricultural management practices, as well as for upscaling the results to a larger geographical area.

References

Alluvione F, Fiorentino N, Bertora C, Zavattaro L, Fagnano M, Chiarandà FQ, Grignani C (2013) Short-term crop and soil response to C-friendly strategies in two contrasting environments. Eur J Agron 45:114–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2012.09.003

Amlinger F, Götz B, Dreher P, Geszti J, Weissteiner C (2003) Nitrogen in biowaste and yard waste compost: dynamics of mobilisation and availability—a review. Eur J Soil Biol 39(3):107–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1164-5563(03)00026-8

Bauer T, Strauss P, Grims M, Kamptner E, Mansberger R, Spiegel H (2015) Long-term agricultural management effects on surface roughness and consolidation of soils. Soil Till Res 151:28–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2015.01.017

Bennett AJ, Bending GD, Chandler D, Hilton S, Mills P (2012) Meeting the demand for crop production: the challenge of yield decline in crops grown in short rotations. Biol Rev 87(1):52–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.2011.00184.x

Blockeel H, Struyf J (2002) Efficient algorithms for decision tree cross-validation. J Mach Learn Res 3:621–650

Bondi G, Creamer R, Ferrari A, Fenton O, Wall D (2018) Using machine learning to predict soil bulk density on the basis of visual parameters: tools for in-field and post-field evaluation. Geoderma 318:137–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2017.11.035

Breiman L, Freidman JH, Olshen RA, Stone CJ (1984) Classification and regression trees. Wadsworth & Brooks, Monterey ISBN:9781351460491

Brouder SM, Gomez-Macpherson H (2014) The impact of conservation agriculture on smallholder agricultural yields: a scoping review of the evidence. Agric Ecosyst Environ 187:11–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2013.08.010

Buczko U, van Laak M, Eichler-Löbermann B, Gans W, Merbach I, Panten K, Peiter E, Reitz T, Spiegel H, von Tucher S (2018) Re-evaluation of the yield response to phosphorus fertilization based on meta-analyses of long-term field experiments. Ambio 47(Supplement 1):50–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-017-0971-1

Bui E, Henderson B, Viergever K (2009) Using knowledge discovery with data mining from the Australian soil resource information system database to inform soil carbon mapping in Australia. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 23:GB4033. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009GB003506

Bullock DG (1992) Crop rotation. Crit Rev Plant Sci 11(4):309–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352689209382349

Cakmak I (2013) Magnesium in crop production, food quality and human health. Plant Soil 368:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-013-1781-2

De’ath G, Fabricius KE (2000) Classification and regression trees: a powerful yet simple technique for ecological data analysis. Ecology 81(11):3178–3192 http://epubs.aims.gov.au/11068/5812

Debeljak M, Džeroski S (2011) Decision trees in ecological Modelling. In: Jopp F, Reuter H, Breckling B (eds) Modelling complex ecological dynamics. Springer, Berlin. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-05029-9_14

Debeljak M, Squire G, Demšar D, Young MW, Džeroski S (2008) Relations between the oilseed rape volunteer seedbank, and soil factors, weed functional groups and geographical location in the UK. Ecol Model 212:138–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2007.10.019

Debeljak M, Cortet J, Demšar D, Krogh PH, Džeroski S (2007) Hierarchical classification of environmental factors and agricultural practices affecting soil fauna under cropping systems using Bt maize. Pedobiologia 51:229–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedobi.2007.04.009

Diepenbrock W, Ellmer F, Léon J (2009) Ackerbau, Pflanzenbau und Pflanzenzüchtung. UTB Verlag Eugen Ulmer Stuttgart. ISBN: 9783825238438

Džeroski S, Goethals B, Panov P (2010) Inductive databases and constraint-based data mining. Springer, New York ISBN: 978-1-4419-7738-0

Fayyad U, Piatetsky-Shapiro G, Smyth P (1996) From data mining to knowledge discovery in databases. AI Mag 17:37–54. https://doi.org/10.1609/aimag.v17i3.1230

Franko U, Spiegel H (2016) Modeling soil organic carbon dynamics in an Austrian long-term tillage field experiment. Soil Till Res 156:83–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2015.10.003

Friedrich T, Derpsch R, Kassam A (2012) Overview of the global spread of conservation agriculture. Field actions science reports, special issue 6, Reconciling Poverty Eradication and Protection of the Environment, http://factsreports.revues.org/1941

Gerendás J, Führs H (2013) The significance of magnesium for crop quality. Plant Soil 368:101–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-012-1555-2

Goldstein A, Fink L, Meitin A, Bohadana S, Lutenberg O, Ravid G (2017) Applying machine learning on sensor data for irrigation recommendations: revealing the agronomist’s tacit knowledge. Precis Agric 47(4):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-017-9527-4

Gransee A, Führs H (2013) Magnesium mobility in soils as a challenge for soil and plant analysis, magnesium fertilization and root uptake under adverse growth conditions. Plant Soil 368(1):5–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-012-1567-y

Grzebisz W (2013) Crop response to magnesium fertilization as affected by nitrogen supply. Plant Soil 368:23–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-012-1574-z

Hazell P, Wood S (2008) Drivers of change in global agriculture. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 363(1491):495–515. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2007.2166

Hijbeek R, van Ittersum MK, ten Berge HFM, Gort G, Spiegel H, Whitmore AP (2017) Do organic inputs matter—a meta-analysis of additional yield effects for arable crops in Europe. Plant Soil 411(1):293–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-016-3031-x

Hobbs PR, Sayre K, Gupta R (2008) The role of conservation agriculture in sustainable agriculture. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 363:543–555. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2007.2169

Jarvis S, Hutchings N, Brentrup F, Olesen JE, Van de Hoek KW (2011) Nitrogen flows in farming systems across Europe. In: Sutton MA, Howard CM, Erisman JW, Billen G, Bleeker A, Grennfelt P, Van Grinsven H, Grizzetti B (eds) The European Nitrogen Assessment, 211–228. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511976988.013

Jiawei H, Kamber M, Pei J (2006) Data mining: concepts and techniques. Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN: 978012381479

Kertész A, Madarász B (2014) Conservation agriculture in Europe. Int Soil Water Conserv Res 2:91–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2095-6339(15)30016-2

Kopittke PM, Menzies NW (2007) A review of the use of the basic cation saturation ratio and the “Ideal” Soil. Soil Sci Soc Am J 71(2):259–265. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2006.0186

Körschens M, Albert E, Armbruster M, Barkusky D, Baumecker M, Behle-Schalk L, Bischoff R, Cergan Z, Ellmer F, Herbst F, Hoffmann S, Hofmann B, Kismanyoky T, Kubat J, Kunzova E, Lopez-Fando C, Merbach I, Merbach W, Pardor MT, Rogasik J, Rühlmann J, Spiegel H, Schulz E, Tajnsek A, Toth Z, Wegener H, Zorn W (2013) Effect of mineral and organic fertilization on crop yield, nitrogen uptake, carbon and nitrogen balances, as well as soil organic carbon content and dynamics: results from 20 European long-term field experiments of the twenty-first century. Arch Agron Soil Sci 59(8):1017–1040. https://doi.org/10.1080/03650340.2012.704548

Kuzmanovski V, Trajanov A, Leprince F, Džeroski S, Debeljak M (2015) Modeling water outflow from tile-drained agricultural fields. Sci Total Environ 505:390–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.10.009

Lehtinen T, Dersch G, Söllinger J, Baumgarten A, Schlatter N, Aichberger K, Spiegel H (2017) Long-term amendment of four different compost types on a loamy silt Cambisol: impact on soil organic matter, nutrients and yields. Arch Agron Soil Sci 63(5):663–673. https://doi.org/10.1080/03650340.2016.1235264

Lehtinen T, Schlatter N, Baumgarten A, Bechini L, Krüger J, Grignani C, Zavattaro L, Costamagna C, Spiegel H (2014) Effect of crop residue incorporation on soil organic carbon and greenhouse gas emissions in European agricultural soils. Soil Use Manage 30(4):524–538. https://doi.org/10.1111/sum.12151

Mirtl M, Bahn M, Battin T, Borsdorf A, Dirnböck T, English M, Erschbamer B, Fuchsberger J, Gaube V, Grabherr G, Gratzer G, Haberl H, Klug H, Kreiner D, Mayer R, Peterseil J, Richter A, Schindler S, Stocker-Kiss A, Tappeiner U, Weisse T, Winiwarter V, Wohlfahrt G, Zink R (2015) Research for the future - LTER-Austria white paper 2015 - on the status and orientation of process oriented ecosystem research, biodiversity and conservation research and socio-ecological research in Austria. In: LTER-Austria series, Austrian Society for Long-Term Ecological Research, Vienna, Austria, pp. 74. ISBN:978-3-9503986-1-8

Poeplau C, Reiter L, Berti A, Kätterer T (2017) Qualitative and quantitative response of soil organic carbon to 40 years of crop residue incorporation under contrasting nitrogen fertilisation regimes. Soil Res 55(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1071/SR15377

Poeplau C, Kätterer T, Bolinder MA, Börjesson G, Berti A, Lugato E (2015) Low stabilization of aboveground crop residue carbon in sandy soils of Swedish long-term experiments. Geoderma 237:246–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2014.09.010

Rashid A, Ryan J (2004) Micronutrient constraints to crop production in soils with Mediterranean-type characteristics: a review. J Plant Nutr 27(6):959–975. https://doi.org/10.1081/PLN-120037530

Schulte RPO, Bampa F, Bardy M, Coyle C, Creamer RE, Fealy R, Gardi C, Ghaely BB, Jordan P, Laudon H, O’Donoghue C, O’hUallacháin D, O’Sullivan L, Rutgers M, Six J, Toth GL, Vrebos D (2015) Making the most of our land: managing soil functions from local to continental scale. Front Environ Sci 3(81). https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2015.00081

Schulte RPO, Creamer RE, Donnellan T, Farrelly N, Fealy R, O’Donoghue C, O’hUallachain D (2014) Functional land management: a framework for managing soil-based ecosystem services for the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Environ Sci Pol 38:45–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2013.10.002

Senbayram M, Gransee A, Wahle V, Thiel H (2015) Role of magnesium fertilisers in agriculture: plant–soil continuum. Crop Pasture Sci 66(12):1219–1229. https://doi.org/10.1071/CP15104

Shekoofa A, Emam Y, Shekoufa N, Ebrahimi M, Ebrahimie E (2014) Determining the most important physiological and agronomic traits contributing to maize grain yield through machine learning algorithms: a new avenue in intelligent agriculture. PLoS One 9(5):e97288. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0097288

Spiegel H, Sandén T, Dersch G, Baumgarten A, Gründling R, Franko U (2018). Soil organic matter and nutrient dynamics following different management of crop residues at two sites in Austria. Book Chapter in “Soil Management and Climate Change: Effects on Organic Carbon, Nitrogen Dynamics and Greenhouse Gas Emissions”, 253–265, Elsevier. ISBN: 978-0-12-812128-3

Spiegel H, Dersch G, Baumgarten A, Hösch J (2010) The international organic nitrogen long-term fertilisation experiment (IOSDV) at Vienna after 21 years. Arch Agron Soil Sci 56:405–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/03650341003645624

Spiegel H, Dersch G, Hösch J, Baumgarten A (2007) Tillage effects on soil organic carbon and nutrient availability in a long-term field experiment in Austria. Die Bodenkultur 58:47–58

Spiegel H, Pfeffer M, Hösch J (2002) N dynamics under reduced tillage. Arch Agron Soil Sci 48:503–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/03650340215644

Spiegel H (2001) Results of three long-term P-field experiments in Austria: 1 Report: Effects of different types and quantities of P-fertiliser on yields and P CAL-contents in soils | Ergebnisse von drei 40-jährigen P-Dauerversuchen in Österreich: 1. Mitteilung: Auswirkungen ausgewählter P-Düngerformen und -mengen auf den Ertrag und die P CAL-Gehalte im Boden. Bodenkultur 52(1):3–17

Tatzber M, Klepsch S, Soja G, Reichenauer T, Spiegel H, Gerzabek M (2015a) Determination of soil organic matter features of extractable fractions using capillary electrophoresis: an organic matter stabilization study in a Carbon-14-labeled long-term field experiment. In: He Z, Wu F (eds) Labile organic matter—chemical compositions, function, and significance in soil and the environment. SSSA Special Publication 62. © 2015. SSSA, Madison. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaspecpub62.2014.0033

Tatzber M, Schlatter N, Baumgarten A, Dersch G, Körner R, Lehtinen T, Unger G, Mifek E, Spiegel H (2015b) KMnO4 determination of active carbon for laboratory routines: three long-term field experiments in Austria. Soil Res 53(2):190–204. https://doi.org/10.1071/SR14200

Tatzber M, Stemmer M, Spiegel H, Katzlberger C, Landstetter C, Haberhauer G, Gerzabek MH (2012) 14C-labeled organic amendments: characterization in different particle size fractions and humic acids in a long-term field experiment. Geoderma 177–178:39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2012.01.028

Tatzber M (2009) Decomposition of Carbon-14-labeled organic amendments and humic acids in a long-term field experiment. Soil Sci Soc Am J 73(3):744–750. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2008.0235

Tatzber M, Stemmer M, Spiegel H, Katzlberger C, Zehetner F, Haberhauer G, Garcia-Garcia E, Gerzabek MH (2009) Spectroscopic behaviour of 14C-labeled humic acids in a long-term field experiment with three cropping systems. Soil Res 47(5):459–469. https://doi.org/10.1071/SR08231

Tatzber M, Stemmer M, Spiegel H, Katzlberger C, Haberhauer G, Gerzabek MH (2008) Impact of different tillage practices on molecular characteristics of humic acids in a long-term field experiment—an application of three different spectroscopic methods. Sci Total Environ 406:256–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.07.048

Trajanov A (2011) Machine learning in agroecology: from simulation models to co-existence rules. Lambert Academic Publishing (LAP), Germany ISBN:978-3845471334

Veenadhari S, Mishra B, Singh CD (2011) Soybean productivity modelling using decision tree algorithms. Int J Comput Appl T 27(7):11–15. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.3852.1846

Witten IH, Frank E (2011) Data mining: practical machine learning tools and techniques - 3rd edition. Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN:978-0-12-374856-0

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted as a part of the LANDMARK (LAND Management: Assessment, Research, Knowledge Base) project. The authors wish to thank David Wall from Teagasc, Ireland, Bhim Bahadur Ghaley from the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, and Kirsten Madena from the The Chamber of Agriculture of Lower Saxony (CALS), Germany, for proofreading the manuscript and providing useful comments.

Funding

LANDMARK has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 635201.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Trajanov, A., Spiegel, H., Debeljak, M. et al. Using data mining techniques to model primary productivity from international long-term ecological research (ILTER) agricultural experiments in Austria. Reg Environ Change 19, 325–337 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-018-1361-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-018-1361-3