Abstract

The Arctic is getting warmer and wetter. Here, we document two independent examples of how associated extreme precipitation patterns have severe implications for high Arctic ecosystems. The events stand out in a 23-year record of continuous observations of a wide range of ecosystem parameters and act as an early indication of conditions projected to increase in the future. In NE Greenland, August 2015, one-quarter of the average annual precipitation fell during a 9-day intensive rain event. This ranked number one for daily sums during the 1996–2018 period and caused a strong and prolonged reduction in solar radiation decreasing CO2 uptake in the order of 18–23 g C m−2, a reduction comparable to typical annual C budgets in Arctic tundra. In a different type of event, but also due to changed weather patterns, an extreme snow melt season in 2018 triggered a dramatic gully thermokarst causing rapid transformation in ecosystem functioning from consistent annual ecosystem CO2 uptake and low methane exchange to highly elevated methane release, net source of CO2, and substantial export of organic carbon downstream as riverine and coastal input. In addition to climate warming alone, more frequent occurrence of extreme weather patterns will have large implications for otherwise undisturbed tundra ecosystems including their element transport and carbon interactions with the atmosphere and ocean.

Similar content being viewed by others

Highlights

-

Extreme events have severe multiple implications for Arctic ecosystems.

-

Cumulative impacts of warming on ecosystem functioning are strongly influenced by single year events.

-

Ecosystem functioning and climate feedbacks in terms of greenhouse gas exchanges will be altered in response to future precipitation events.

Introduction

Global circulation models predict a strong increase in Arctic precipitation during the twenty-first century as a consequence of anthropogenic climate change (Stocker and others 2013). Depending on the emission scenario used, precipitation is projected to increase by 35–60% (Stocker and others 2013; Bintanja and Selten 2014; Vihma 2014), while precipitation extremes are likely to become more frequent (Toreti and others 2013). As with temperature increases, regional differences in the projected pattern of precipitation increase exist and they are regulated by spatial variability in open water, moisture transport, and circulation patterns (Bengtsson and others 2011). The projected increase in Arctic precipitation is derived from two main sources: 1) enhanced surface evaporation mainly resulting from retreating sea ice and 2) enhanced moisture transport towards the poles due to transient cyclones (Bintanja and Selten 2014; Bengtsson and others 2011; Kug and others 2010a, b; Zhang and others 2013). The first, more local source, is expected to dominate the overall precipitation increase with peaking contribution in late autumn and winter. The latter, more remote moisture source, will dominate the summer and early autumn precipitation increase (Bintanja and Selten 2014). Precipitation in the Arctic is currently dominated by snowfall (65% of total), although recent modelling efforts indicate a transition towards rain (snow decreasing to 40% of total) by the end of the twenty-first century (Bintanja and Andry 2017) along with a rise in air temperatures (AMAP 2017).

A tendency towards more intense rain events along the Greenland ice sheet margin has already been observed (Doyle and others 2015). Wintertime snow depths are expected to increase, especially in the high Arctic (Stendel and others 2008), but with a gradually higher rain-to-snowfall ratio leading to longer snow-free periods with consequences for glaciers, permafrost, flora and fauna, fjords, sea ice, and the Arctic Ocean. In the shorter term, however, more extreme snow conditions may well be expected.

An intensified Arctic hydrological cycle will also increase other components of the catchment water budget, including evapotranspiration, run-off, and discharge. Already now, Arctic river discharge has been observed to be increasing (Vihma 2014; Peterson and others 2002; Rysgaard and Glud 2007), resulting in enhanced transport of freshwater, organic matter, and nutrients to near-coastal zones (Bring and others 2016). Additional increases in river discharge will reinforce the freshening of the Arctic Ocean and influence ocean circulation (Peterson and others 2002; Sejr and others 2017). The effect of increased precipitation on Arctic ecosystems will be further modified by other expected changes in the Arctic terrestrial domain, such as thawing permafrost (Romanovsky and others 2010) and changes in vegetation growth and composition (Myers-Smith and others 2011).

Not only landscapes with permafrost covering less than 0% are found susceptible to abrupt thaw events, such as thermokarsts and associated with carbon releases, but both their area and frequency are modelled also to increase until 2300 under current RCP scenarios (Turetsky and others 2019).

Due to the scarcity of environmental monitoring activities in high latitudes, the ecosystem response to increased precipitation and especially extreme rain and snow events is largely unknown (Bring and others 2016). There is an urgent need for observational data to help us understand how changes in essential climate variables regulate ecosystem dynamics as these may have important feedback effects on the climate system, e.g. through changes in the surface energy balance and greenhouse gas budgets. Comprehensive data that document this whole range of different landscape components are very rare, but here, we describe and quantify environmental effects of two different recent events with in situ data and briefly review further examples (Figure 1). The two events are (1) an extreme, 9-day long rain event in 2015, and (2) a late and unusually heavy snow season in 2018. These events occurred in high Arctic Zackenberg, northeast Greenland (Figure 2). We focus here on interrelated ecosystem processes affected by these two unusual events, respectively: the short- and longwave radiation components, river discharge and transport of sediments and organic matter, the fast alteration of the landscape, and the land–atmosphere exchange of CO2 and CH4. Wider consequences of the 2018 extreme snow event for different aspects of ecosystem reproduction are discussed recently elsewhere (Schmidt and others 2019).

Conceptual diagram showing the foci of the current paper. Projections forecast increased precipitation and more extreme precipitation events in the Arctic. Presented is a review of two extreme events from the 25-year record from the Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring (GEM) Programme at Zackenberg, NE Greenland (Figure 2), and the knock-on effects on downstream ecosystems. Both extreme precipitation events are of a nature that are projected to increase in intensity and frequency in the future.

Map of the Zackenberg watershed and location of A.P. Olsen Ice Cap (left). The red square indicates the inset map to the right, which is a high-resolution RGB image derived from an UAV mapping campaign in 2014. The locations of the research station, climate station, Zackenberg River hydrometric station, thermokarst, and eddy covariance site (Zackenberg Fen) are indicated with black dots. See Figure 5 for the position of Zackenberg in Greenland. Datum: WGS84, projection: UTM zone 27N, source: Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring (GEM) Programme.

Methods

Research Site

The research site used in this study, Zackenberg (74.5°N, 20.6°E), is located in NE Greenland. The valley is surrounded by mountains (> 1000 m a.s.l) to the west, east, and north, while a fjord forms its southern boundary. The climate is high Arctic with mean annual temperature of − 9.0°C and total annual precipitation of 211 mm, of which most falls as snow during the 8–9 month long winter period (Hansen and others 2008). Annual mean temperature has increased by 0.06°C y−1 since 1996, with most pronounced warming occurring during summer months (Abermann and others 2017). The Zackenberg valley can be divided into a western part dominated by gneiss and granite bedrock and an eastern part dominated by sedimentary and basaltic bedrock (Cable and others 2018). The area is underlain by continuous permafrost, with maximum thaw depths reaching 0.5–1.0 m dependent on substrate type. During 1997–2010, the summertime maximum thaw depth increased by 1.6 cm y−1 in a Circumpolar Active Layer Monitoring (CALM) grid (Lund and others 2014). The onset of permafrost aggradation in the Zackenberg region was initiated after deglaciation during the early Holocene following sea-level decline. The formation of epigenetic massive ice bodies and cryofacies was interpreted by Gilbert and others (2017) to have formed from recharge to the local groundwater systems by glacial meltwater or brackish seawater.

Most vegetated surfaces are located below 300 m a.s.l. At least five plant community classes can be identified (Elberling and others 2008): fens occurring in water-saturated areas, grasslands in semi-sloping, wet-to-moist terrain, Salix arctica snowbeds in slopes with prolonged snow cover, Cassiope tetragona heaths in drier, level ground, and Dryas spp. heath in dry and wind-exposed areas. The main river in the valley, the Zackenberg River, drains an area of 514 km2, of which 92 km2 is covered by glaciers (Figure 2; Citterio and others 2017).

Measurements and Data Processing

Extensive climate and ecosystem data from Zackenberg are provided by the Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring (GEM) Programme, an integrated monitoring and long-term research programme. In this study, data from the ClimateBasis and GeoBasis sub-programmes were used, and these data are freely accessible from the GEM database at http://data.g-e-m.dk. We used standard meteorological observations 1996–2018 from climate masts located close to the Zackenberg Research Station. Measurements include air temperature, precipitation, snow depth, and shortwave and longwave incoming and outgoing radiation. Timing of snowmelt was identified as the date for which the ground in the main research area was snow free. NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis data for 1000 hPa air temperature and surface precipitation (Kalnay and others 1996) have been used in order to put the results into a larger spatio-temporal context, and access has been gained through http://www.esrl.noaaa.gov/posd/.

Discharge in the Zackenberg River was measured near the research station and the river delta. We measured water level automatically with a sonic ranger and the values were converted into discharge using a stage–discharge relation. We re-calibrated the stage–discharge curve every year to account for changes in the riverbed, particularly related to periodic a glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF) from A.P. Olsen Ice Cap (Ladegaard-Pedersen and others 2017). Depth-integrated water samples were collected on 3 days per week, in the morning (08:00 h EGST) and in the evening (20:00 h EGST). The sampling frequency was increased during periods with high discharge. Suspended sediment concentration was determined by filtering water through a 0.7 µm filter (Whatman GF/F glass fibre, 47 mm diameter) and weighing the dried filter prior to and after filtration. Suspended organic matter in the sediment was determined by loss on ignition (Dean 1974) at the Department of Geoscience and Natural Resource Management, University of Copenhagen. The flux of suspended sediments and organic matter was determined using an uncorrected rating curve following the procedure described in Ladegaard-Pedersen and others (2017).

Three soil cores of roughly 30 cm length were taken at the thermokarst site, which were divided into three horizons of 10 cm each. An additional sample included a pooled silt layer. Soil carbon analysis of these solid soil samples included loss-on-ignition analysis conducted at Bioscience, Risø, Aarhus University, for which roughly 10 g of wet soil samples was weighted in three replicates each. After 48 h at 70°C, the dry weight was measured and total water content calculated. Organic material was combusted at 450°C for 48 h and the loss in weight measured as soil organic matter content (Table 1).

Radiocarbon dating was conducted at the Department of Geology, Lund University, on the same cores and horizons as described above. Wet soil was homogenized, sifted with water in a 0.5 mm sieve and large organic material, such as twigs and moss residues, selected, and stored in deionized water. Under the stereomicroscope, any roots perturbing through the selected soil layer from younger areas were removed from these samples. After a HCl and NaOH pre-treatment, sample weight was measured ranging from 0.7 to 1.6 mg C and the ratio of C isotopes was measured using an accelerator mass spectrometer. The obtained peaks were compared to established 14C calibration curves. The resulting age descriptions include samples younger than 1963 (fM = fraction modern), which was obtained through comparison of 14C profiles in tree rings. Samples from 1650 to 1950 were labelled BP (= before present) (Table 1).

Eddy covariance measurements of the land–atmosphere exchange of CO2 were conducted in a fen ecosystem located ca. 1.4 km NE of the research station (Figure 2). The system consisted of a closed-path infrared gas analyser LI-6262 (LI-COR Inc., USA) and 3D sonic anemometer Gill R2 (Gill Instruments Ltd., UK) until August 2011, when it was upgraded to an enclosed-path LI-7200 (LI-COR Inc., USA) and Gill HS (Gill Instruments Ltd., UK). High-frequency CO2 concentration and wind components data were processed according to standard flux community procedures (cf. Aubinet and others 2000), including despiking, 2D coordinate rotation, time lag removal by covariance optimization, block averaging, frequency response correction, and Webb–Pearman–Leuning correction. More information on the EC system setup, flux computation, post-processing, and quality checks can be found in Lund and others (2012a, b); Stiegler and others (2016), and about the flux gap-filling using marginal distribution sampling in (López-Blanco and others 2017).

CO2 fluxes as measured by the EC technique have been reported previously (Lund and others 2012a, b). Automatic chambers measuring both CO2 and CH4 in nearby habitats for more than 10 years have also been documented (Mastepanov and others 2013; Pirk and others 2016).

The immediate measurements of CH4 and CO2 concentrations in the near-surface air at the thermokarst site in 2018 were made using a portable gas analyser (M-GGA-918, Los Gatos Research, USA). Similar air samples (about 3 l each, transported in metal containers) were taken for isotopic analysis at the automatic chamber measurement hut about 1 km from the site. Here, these samples were injected into a 13CH4 analyser (MCIA1-912, Los Gatos Research, USA).

UAV-based mapping of the thermokarst was made by combining images collected on four different days using different image sensors and platforms. Each image overlaps the neighbouring image by at least 70% both horizontally and vertically. Each sensor has different specifications, and images were captured at a different elevation above ground. These differences including the number of images, ground-sampling distance (GSD), ground control points (GCPs), and the area covered are summarized in supplementary Table S1.

Results

Local Meteorology and Radiation Budget

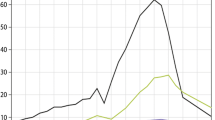

The summertime (June–August) mean temperature in Zackenberg in 2015 was 4.7°C, similar to the long-term (1996–2014) mean (4.7 ± 1.0°C) with 2018 being colder, 2.3°C. The end-of-winter snow depth in 2015 (1.3 m) was among the highest on record (long-term mean 82 ± 38 cm), but in 2018, it was even higher, 1.4 m. The snowpack usually lasts into summer (25 June on average). In 2015, it did not disappear until 3 July, while in 2018, the end of the snowmelt period was 17 days later on the 20 July (Figure 3). Thus, the 2018 summer snow melt was the latest on record (Figure 3). This had a strong impact on the surface energy balance. The outgoing shortwave radiation, which usually decreases by June along with the snow pack, remained high until mid-July. Between 8 and 16 August 2015, 91 mm precipitation fell as rain with almost half of the rainfall occurring on 13 August (41 mm). Considering only rain events, the August 2015 event ranks number one both for daily and for 5-day sums (Figure 3). The annual precipitation in 2015, 339 mm, is the highest on record. The site has seen soil warming at all depths over the period 1996–2018 most significantly since 2013 and during the winter (Figure 4).

Air temperature, snow depth, and precipitation measured at the main climate station in Zackenberg left y-axis: daily average temperature and snow depth. Blue shaded area represents range between min and max daily air temperature averages for 1996–2017. Solid lines are daily average air temperature in 2015 (blue) and 2018 (black). Dashed lines are snow depth: 2015 (blue), 2018 (black), individual years 1996–2017 (grey). Right y-axis: mean precipitation on individual dates during the entire 1996–2018 period (light grey bars), 2015 precipitation (dark grey bars).

During the extreme rain event in 2015, shortwave radiation was significantly reduced as a consequence of persistent thick cloud cover (Figure S1a). Although the longwave radiation balance became very small (high incoming radiation balanced by similar emitted radiation, Figure S1b), the shortwave incoming radiation was exceptionally low with values between 15 and 30% of the long-term mean for the specific period. This manifested in the lowest-ever recorded monthly mean incoming shortwave radiation values. During the rain event, the mean daily net radiation was 27 ± 16 W m−2 (compared to the long-term average around 175 W m−2, Figure S1a).

Synoptic Conditions

Two marked low-pressure systems influenced the particular weather evolution in mid-August 2015 (see supplementary information Figure S2). A pronounced low-pressure system with its centre just off Greenland’s west coast north of Disko Island weakened and moved further southeast, while a minor Iceland low and the associated frontal system were responsible for the first period of precipitation until 12 August. The bulk of precipitation occurred 13 August when as a relic of the first low-pressure system expansion, an even stronger Iceland low developed with its centre just off Iceland’s southeast coast. Moist air masses were thus advected with this cyclone towards Greenland’s East coast (Figure 5A).

Two additional features, different to the ones in 2015, made the 2018 season extraordinary. While more than average snow cover fell during winter, a persistent cold outbreak of polar air resulted in lower than average summer temperatures for most of Greenland (Figure 5B). Most remarkably, this same pattern caused the extreme heat wave in western Europe (a corner of which is shown in Figure 5B).

River Discharge, Suspended Sediment, and Organic Matter Transport in 2015

The drainage basin covers an area of 512 km2, of which 20% is glaciated and 10% covered by lakes. The largest contribution of water into the Zackenberg River Catchment is meltwater from the A.P. Olsen glacier (Ladegaard-Pedersen and others 2017), and there is an approximate 12 h delay for the glacier meltwater to reach the Zackenberg monitoring station as the water passes through lake Store Sødal. Discharge in the river increased during the rain event in 2015 (Figure 6). The discharge maximum lasted 11–21 August, thus a few days delay compared with the rain event (8–16 August). The maximum river discharge rate, occurring 14 August, was 8.7 × 106 m3 day−1, which was the highest rate during 2015. The total discharge during 2015 was 268 × 106 m3 (long-term 1997–2014 mean: 192 ± 45 × 106 m3 y−1), to which the rain events contributed 8%.

A Daily discharge in the Zackenberg River in 2015 and mean, minimum, and maximum values during the period 1996–2018. B Daily suspended sediment load (black) and organic matter (blue) in the Zackenberg River during 2015. The grey shaded area indicates the rain event period. The GLOF (see text) in 2015 is visible on 1 August.

The total suspended sediment (SS) load in 2015 was approximately 112 × 106 kg, of which approximately 5.8 × 106 kg is organic matter (OM). Although the rain event only lasted 9 days, it accounted for 58 and 51% of annual SS and OM load, respectively.

Thermokarst Development, Trace Gas Exchange, and Carbon Loss in 2018

The thermokarst caused a complete change in the soil appearance and characteristics over an area of 198 m2 from 28 June to 7 August 2018 and a total of 219 m2 from 28 June to 9 September (Figure 7). Soil profile characteristics before and after the collapse are quantified in Table 1. The top 30 cm of soil overlaying a segregated ice layer between 30 and 60 cm depth was all eroded along with part of the underlying inorganic silt. A total of roughly 360 m3 of permafrost soil and ice was washed away (and/or oxidized) from the small area from 28 June to 9 September.

A A drone photograph taken in south-westerly direction of the thermokarst area with Zackenberg research station in the background. The area within the white dotted line is the thermokarst study area analysed in the images pictured in (B). Photograph: Lars Holst Hansen. B Drone images analysed for spatial and volumetric development of the thermokarst between 23 August 2014 and on three occasions during the summer of 2018. The area estimated covered by the thermokarst is inserted.

The 14C dating of the soil profile shows a typical floodplain signature filling in with terrestrial organic soil built up over the past 2–300 years (Table 1). To assess the likely source of the water in the segregated ice layer, we compared the major element chemistry of the segregated ice (see supplementary information) with published river chemistry data from the main Zackenberg River, tributaries draining into the main river (Hasholt and Hagedorn 2000), and soil pore waters from regions with different vegetation and soil moisture contents within the Zackenberg River Catchment. The segregated ice composition is distinct from tributaries draining the sedimentary and basaltic bedrock, and the main Zackenberg River (data.g-e-m.dk). Likewise, the segregated ice chemistry is dissimilar to soil pore waters from water-saturated fen and wet-to-moist grasslands areas. The segregated ice is most similar to soil pore waters draining drier heath vegetation and published compositions of snow and the Zackenberg River draining exclusively Caledonian crystalline basement downstream of the A.P. Olsen Ice Cap and Store Sødal (Hasholt and Hagedorn 2000). The segregated ice chemistry therefore suggests that the segregated ice formed from dilute glacial meltwater or groundwater rather than seawater (see Table S2 for details).

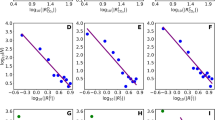

Greenhouse gas exchange and storage are composed of a well-documented CO2 exchange over more than 10 years of eddy covariance (EC) measurements with the same composite vegetation characteristics (Figure 8) and methane exchange measurements made in multiple projects in the area of the site starting with Christensen and others (2000). The exposed segregated ice formations in the soil hold elevated concentrations of methane in the order of 10 ppm, a five times higher concentration than the ambient air currently holds (Table 1). Moreover, the free air in the cracks of the thermokarst has elevated concentrations of methane of up to more than 30 ppm indicating a substantial point source to the atmosphere. The accumulated methane in the cracks has similar isotopic values to the methane trapped in the segregated ice of about − 60 δ13CH4; this number should be compared with the atmospheric background of − 42 δ13CH4 (Table 1).

Daily land–atmosphere exchange of CO2 fluxes 2008–2018 from the eddy covariance site located at the fen ecosystem in Zackenberg. The 2015 time series is highlighted with solid lines and symbol markers, along with other years with similar seasonality (2008 and 2014); The 2018 time series is also highlighted with symbol markers. Other years are marked with dashed lines. Grey areas highlight the extreme snowmelt season in 2018 (1) and the rain event period in 2015 (2). The two right panels zoom-in on 2018 and 2015 periods comparing the 9-day average exchange of CO2 with the 2008–2017 years (1) and the years with similar seasonality (2). It is clear that any temporal trend over the years is clearly superseded by the extreme events.

Land–Atmosphere CO2 Exchange

Due to late snowmelt in 2015 (Figure 3), the active fen ecosystem period did not switch into a daily sink for atmospheric CO2 until 15 July (Figure 8). This was similar to other snow-rich years such as 2008 and 2014, when daily net CO2 uptake began 10 and 16 July, respectively. In other years for which CO2 flux measurements are available, snow melted earlier resulting in earlier leaf out and onset of the daily net CO2 uptake period. Late onset of vegetation growth led to late peak greenness and maximum CO2 uptake (maximum daily CO2 uptake in snow-rich years 2008, 2014 and 2015 occurred 31 July, 27 July, and 4 August, respectively), compared with years presenting early snowmelt (maximum daily CO2 uptake in 2010, 2011, 2013, 2016, and 2017 occurred 15, 17, 15, 15, and 18 July, respectively). The latest snowmelt season in the fen ecosystem during the 2008–2018 period occurred in 22 July 2018. The system switched from daily source to sink of CO2 on 8 August. Based on Julian days, the snowmelt period and the beginning of the growing season were 17% and 18% later than the 2008–2017 mean, respectively. Compared to the 2008–2017 mean, this especially delayed growing season resulted in the latest maximum daily CO2 uptake (22 August compared to 21 July) and the shortest growing season (25 days compared to 46 days).

During the rain event 8–16 August 2015, daily CO2 fluxes were close to zero (Figure 8) due to low levels of solar radiation limiting photosynthetic CO2 uptake (Figure S1). The average CO2 exchange during this period in 2015 was − 0.09 g C m−2 day−1. This number can be compared with the CO2 budgets for the 8–16 August period in 2008 and 2014, 2 years with similar seasonality as driven by snow conditions in previous winters, being − 2.06 and − 2.60 g C m−2 day−1, respectively (Figure 8, sub-panel 2). Immediately after the rain event, when incoming ground radiation levels returned to normal (Figure S1), the fen ecosystem returned to being a net daily sink for atmospheric CO2 until the daily net CO2 uptake period ended on 3 September, which was similar (but later) to 2008 and 2014 (24 and 30 August, respectively). During the 9-day mean at each side of the snowmelt period capturing the highest CO2 respiration before the growing season, 2018 featured an average release of 1.4 g C m−2 day−1. The net ecosystem exchange in the 2008–2017 period was − 3.1 g C m−2 day−1, therefore 2018 experienced a 314% weaker C sink strength than the rest of the years (Figure 8, sub-panel 1), and was acting as a net source of C.

Discussion

Advection of moist air masses from lower latitudes will become more frequent in the future as poleward transport of atmospheric moisture is expected to increase with climate change (Bengtsson and others 2011; Kug and others 2010a, b), especially during spring, summer, and autumn (Bintanja and Selten 2014). Increased precipitation rates, both in terms of mean values and extremes, will have profound effects on Arctic ecosystems. The two recent events described here, occurring in 2015 and 2018 in Zackenberg, Northeast Greenland, were examples of such a changing pattern of climate. The data show effects on local radiation balance, vertical exchange of CO2, river discharge, organic matter transport, ground subsidence, and altered methane emission, within a high Arctic catchment. As such they provide examples of consequences for ecosystems in the Arctic that go beyond those induced by gradual warming in itself and extend the consequences to be highly dependent on changes in weather patterns. Such changes in climate may be locally much more pronounced for ecosystem change and feedbacks on climate than the warming in itself.

Although temperature anomalies are widely observed to accelerate thermokarst development (Lewkowicz and Way 2019), only few publications discussed the effect of intensity and frequency of precipitation events on permafrost degradation. Kokelj and others (2015) reviewed four parameters to steer precipitation-driven permafrost erosion, even at stable thermal conditions, including: (1) sensible and latent heat transfer within the active layer, (2) mobilization of transported material, (3) thermoerosion, and (4) slope instability (Kokelj and others 2015). High-intensity, low-frequency precipitation events are accountable for the majority of sediment mass flux from permafrost, furthermore leading to decreased soil strength, higher soil moisture levels especially in ice-rich permafrost grounds and consecutively elevated anaerobic microbial CH4 emission (Lee and others 2015).

Incoming shortwave radiation is the dominant energy source for tundra environments during the snow-free period (Westermann and others 2009). During the rain event in 2015, shortwave radiation was heavily reduced because of thick cloud cover (Figure S2), resulting in record low mean daily net radiation (27 ± 16 W m−2) and thus little available energy for sensible, latent, and ground heat flux. The daily cycle of active layer soil temperatures was largely diminished, and we observed no strong effects of water percolation on soil thermal state (data not shown). Clouds generally have a positive radiative effect over ice- and snow-covered surfaces; however, over snow-free tundra surfaces, clouds have a cooling effect (Lund and others 2017a, b). The impact of projected future increase in cloudiness (Stocker and others 2013) on Arctic surface energy availability is thus highly dependent on surface type and snow cover. The same effects, but for different reasons, were apparent with the much prolonged snow season in 2018.

After the 2015 rain event, it was speculated that a similar event during the green-up period would likely have delayed plant growth with additional implications causing an intensified decrease in carbon uptake. This was proven true but just through the prolonged snow cover in 2018. We observed neither instant nor legacy effects on the ability of the fen vegetation to assimilate carbon due to the rain event, which can be explained by the timing of the events that made any recovery happen towards the end of the growing season. Thus, similar as for drought events (Lafleur 2009; Lund and others 2012a, b), the timing, severity, and duration of extreme events which may also be of biotic nature (Lund and others 2017a, b) are important for the net effect on ecosystem productivity and CO2 budgets.

By comparing the CO2 budget in the fen during the rain event in 2015 (Figure 8; − 0.8 g C m−2) with the budgets from the same periods in 2 years with similar seasonality, 2008 (− 18.5 g C m−2) and 2014 (− 23.4 g C m−2), it can be argued that the 2015 rain event reduced CO2 uptake in the order of 18–23 g C m−2. This reduction is similar to typical Arctic wetland ecosystem annual C budgets (Parmentier and others 2011; López-Blanco and others 2017, 2018). Similarly, the cumulative CO2 budget at the end of the snowmelt period in 2018 (Figure 8; 1.4 g C m−2) was significantly less productive compared to previous years (− 27.8 g C m−2), corresponding to a lower C uptake of 29.3 g C m−2 on average, a slightly stronger effect than the 2015 event.

Both observed reductions in CO2 sink strength in Zackenberg were a result of strongly reduced solar radiation available at the surface (for 2015 see Figure S1a). Summertime CO2 uptake may thus be reduced in a cloudier future, especially during periods with thick cloud cover. However, hydrology will play a key role in modifying Arctic tundra greenhouse gas exchange, as controlled by the complex interplay between permafrost thaw and increasing precipitation and evapotranspiration (Hinzman and others 2013). Future CO2-to-CH4 ratios are likely to be regulated by changes in soil moisture and the distribution of meltwater ponds in the landscape, as well as resulting changes in soil community profiles.

The rapid thermokarst development in 2018 (Figure 7) showed a potential for total ecosystem disruption following a high precipitation event triggering surface collapse. Similar intense rain events coupled with early snow melt and increased ambient temperatures led to several thaw slumps in 2004 within Alaskan permafrost soils (Balser and others 2014). The analyses of the soil profile (Table 1) show that this disruption is affecting the most recent centennial-scale ecosystem development and essentially turns the soil development back some 300 years most likely to a time where the little ice age caused a build-up of ice in the ground and with low temperature slowing decomposition accumulation of soil carbon was initiated. The inorganic chemical characteristics of the segregated ice resemble that of present-day river run-off from higher up in the catchment (Hasholt and Hagedorn 2000) and that of soil pore waters from heath vegetated areas. Given the thermokarst developed in a flat grassy heathland region on the banks of the present-day Zackenberg River, these results suggest that dilute surficial water draining the A.P. Olsen Ice Cap and/or snow melt is a likely source of the water, and concomitant pore water processes in dry heath vegetation and subsequent freeze–thaw processes resulted in formation of the segregated ice.

Increased methane concentrations in the cracks of the thermokarst combined with the loss of stored organic soil carbon and strongly reduced plant uptake (at least in the short term) suggest a further change towards the ecosystem becoming a source of both CO2 and CH4 where it otherwise was a minor but consistent sink for both CO2 (Zhang and others 2018) and CH4 (Christensen and others 2000; Jørgensen and others 2014).

Antecedent soil conditions are important for the impact of heavy rain events on run-off, discharge, and sediment transport (Favaro and Lamoureux 2014; Abermann and others 2019). Both active layer depth and soil moisture content regulate the soil water infiltration and hence storage capacity and thus the amount of run-off in the watershed. The extreme rain event in 2015 increased the transport of suspended sediment and organic matter dramatically, generating 58 and 51% of the annual load, respectively (Figure 6), contributing more than the periodic GLOF (Ladegaard-Pedersen and others 2017). It is known that summer rainfall in Arctic watersheds can mobilize substantial amounts of sediment (Rysgaard and Glud 2007; Favaro and Lamoureux 2014; Rasch and others 2000; Beylich and others 2006), especially in areas with sparsely vegetated, sedimentary mountain slopes and fine-grained lowland areas with shallow active layers (Rasch and others 2000). Again, the soil moisture conditions prior to extreme events regulate the impact on sediment transport (Favaro and Lamoureux 2014). Saturated soil conditions in the active layer result in overland flow and enhanced surface erosion. Also, moister soils resulting in lower oxygenation promote growth of anaerobic microbes, metabolizing the soil organic carbon and making it a more labile source of CO2 and CH4 (Bragazza and others 2013; Lee and others 2014).

The projected increase in summer precipitation (Stocker and others 2013; Bintanja and Selten 2014) especially in precipitation extremes will have large effects on the transport of materials from terrestrial to marine ecosystems, affecting downstream aquatic and marine environments (Bring and others 2016) and ocean circulation (Sejr and others 2017). Furthermore, ongoing permafrost thaw in the Arctic region has been observed to cause a northward shift of the Siberian boundary of continuous permafrost (Romanovsky and others 2010) and can, as shown, affect the landscape stability dramatically resulting in increased sediment erosion rates.

The environmental effects we observe are able to quantify constitute important showcases for the response of Arctic ecosystems to specific features of climate change as expected to become more frequent in coming decades. The results offer an unprecedented insight into the detailed response to change in frequency and intensity of certain weather patterns, for fundamental natural ecosystem functioning in the Arctic. These events may represent more detrimental effects on ecosystems than the gradual warming climate per se. As such, they also demonstrate the value of more integrated, long-term environmental monitoring programs in remote and sensitive regions, where the forecasted consequences of climate change are already taking place.

Data Availability

Data for this study were provided by the Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring Programme (http://data.g-e-m.dk) in particular the Climatebasis and Geobasis subprograms.

References

Abermann J, Hansen B, Lund M, Wacker S, Karami M, Cappelen J. 2017. Hotspots and key periods of Greenland climate change during the past six decades. Ambio 46:S3–11.

Abermann J, Eckerstorfer M, Malnes E, Hansen BU. 2019. A large wet snow avalanche cycle in West Greenland quantified using remote sensing and in situ observations. Nat Hazards 97:517–34.

AMAP. 2017. Snow, water, ice and permafrost in the arctic (SWIPA) 2017. In: xiv-269 pp. Oslo, Norway: Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP).

Aubinet M, Chermanne B, Vandenhaute M, Longdoz B, Yernaux M, Laitat E. 2000. Long term carbon dioxide exchange above a mixed forest in the Belgian Ardennes. Agric For Meteorol 108:293–315.

Balser AW, Jones JB, Gens R. 2014. Timing of retrogressive thaw slump initiation in the Noatak Basin, northwest Alaska, USA. J Geophys Res-Earth Surf 119:1106–20.

Bengtsson L, Hodges KI, Koumoutsaris S, Zahn M, Keenlyside N. 2011. The changing atmospheric water cycle in Polar Regions in a warmer climate. Tellus Ser A-Dyn Meteorol Oceanogr 63:907–20.

Beylich AA, Sandberg O, Molau U, Wache S. 2006. Intensity and spatio-temporal variability of fluvial sediment transfers in an Arctic-oceanic periglacial environment in northernmost Swedish Lapland (Latnjavagge catchment). Geomorphology 80:114–30.

Bintanja R, Andry O. 2017. Towards a rain-dominated Arctic. Nat Clim Change 3:1556.

Bintanja R, Selten FM. 2014. Future increases in Arctic precipitation linked to local evaporation and sea-ice retreat. Nature 509:479–82.

Bragazza L, Parisod J, Buttler A, Bardgett RD. 2013. Biogeochemical plant–soil microbe feedback in response to climate warming in peatlands. Nat Clim Change 3:273–7.

Bring A, Fedorova I, Dibike Y, Hinzman L, Mard J, Mernild SH, Prowse T, Semenova O, Stuefer SL, Woo MK. 2016. Arctic terrestrial hydrology: a synthesis of processes, regional effects, and research challenges. J Geophys Res-Biogeosci 121:621–49.

Cable S, Christiansen HH, Westergaard-Nielsen A, Kroon A, Elberling B. 2018. ‘Geomorphological and cryostratigraphical analyses of the Zackenberg Valley, NE Greenland and significance of Holocene alluvial fans. Geomorphology 303:504–23.

Christensen TR, Thomas Friborg M, Sommerkorn JK, Illeris L, Soegaard H, Nordstroem C, Jonasson S. 2000. Trace gas exchange in a high-arctic valley 1. Variations in CO2 and CH4 flux between tundra vegetation types. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 14:701–13.

Citterio M, Sejr MK, Langen PL, Mottram RH, Abermann J, Larsen SH, Skov K, Lund M. 2017. Towards quantifying the glacial runoff signal in the freshwater input to Tyrolerfjord-Young Sound, NE Greenland. Ambio 46:S146–59.

Dean WE. 1974. Determination of carbonate and organic-matter in calcareous sediments and sedimentary-rocks by loss on ignition—comparison with other methods. J Sediment Petrol 44:242–8.

Doyle SH, Hubbard A, van de Wal RSW, Box JE, van As D, Scharrer K, Meierbachtol TW, Smeets PCJP, Harper JT, Johansson E, Mottram RH, Mikkelsen AB, Wilhelms F, Patton H, Christoffersen P, Hubbard B. 2015. Amplified melt and flow of the Greenland ice sheet driven by late-summer cyclonic rainfall. Nat Geosci 8:647.

Elberling B, Tamstorf MP, Michelsen A, Arndal MF, Sigsgaard C, Illeris L, Bay C, Hansen BU, Christensen TR, Hansen ES, Jakobsen BH, Beyens L. 2008. Soil and plant community-characteristics and dynamics at Zackenberg. Adv Ecol Res 40(40):223–48.

Favaro EA, Lamoureux SF. 2014. Antecedent controls on rainfall runoff response and sediment transport in a high arctic catchment. Geogr Ann Ser A Phys Geogr 96:433–46.

Gilbert GL, Cable S, Thiel C, Christiansen HH, Elberling B. 2017. Cryostratigraphy, sedimentology, and the late Quaternary evolution of the Zackenberg River delta, northeast Greenland. Cryosphere 11:1265–82.

Hansen BU, Sigsgaard C, Rasmussen L, Cappelen J, Hinkler J, Mernild SH, Petersen D, Tamstorf MP, Rasch M, Hasholt B. 2008. Present-day climate at Zackenberg. Adv Ecol Res 40(40):111–49.

Hasholt B, Hagedorn B. 2000. Hydrology and geochemistry of river-borne material in a high arctic drainage system, Zackenberg, Northeast Greenland. Arct Antarct Alp Res 32:84–94.

Hinzman LD, Deal CJ, David McGuire A, Mernild SH, Polyakov IV, Walsh JE. 2013. Trajectory of the Arctic as an integrated system. Ecol Appl 23:1837–68.

Jørgensen CJ, Johansen KML, Westergaard-Nielsen A, Elberling B. 2014. Net regional methane sink in high Arctic soils of northeast Greenland. Nat Geosci 8:20–3.

Kalnay E, Kanamitsu M, Kistler R, Collins W, Deaven D, Gandin L, Iredell M, Saha S, White G, Woollen J, Zhu Y, Chelliah M, Ebisuzaki W, Higgins W, Janowiak J, Mo KC, Ropelewski C, Wang J, Leetmaa A, Reynolds R, Jenne R, Joseph D. 1996. The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 77:437–71.

Kokelj SV, Tunnicliffe J, Lacelle D, Lantz TC, Chin KS, Fraser R. 2015. Increased precipitation drives mega slump development and destabilization of ice-rich permafrost terrain, northwestern Canada. Glob Planet Change 129:56–68.

Kug JS, Choi DH, Jin FF, Kwon WT, Ren HL. 2010. Role of synoptic eddy feedback on polar climate responses to the anthropogenic forcing. Geophys Res Lett 37.

Kug JS, Jin FF, Ren HL. 2010. Role of synoptic eddies on low-frequency precipitation variation. J Geophys Res-Atmos 115.

Ladegaard-Pedersen P, Sigsgaard C, Kroon A, Abermann J, Skov K, Elberling B. 2017. Suspended sediment in a high-Arctic river: an appraisal of flux estimation methods. Sci Total Environ 580:582–92.

Lafleur PM. 2009. Connecting atmosphere and wetland: trace gas exchange. Geogr Compass 3:560–85.

Lee EJ, Merriwether DA, Kasparov AK, Nikolskiy PA, Sotnikova MV, Pavlova EY, Pitulko VV. 2015. Ancient DNA analysis of the oldest canid species from the Siberian Arctic and genetic contribution to the domestic dog. PLOS ONE 10.

Lee H, Swenson SC, Slater AG, Lawrence DM. 2014. Effects of excess ground ice on projections of permafrost in a warming climate. Environ Res Lett 9:124006.

Lewkowicz AG, Way RG. 2019. Extremes of summer climate trigger thousands of thermokarst landslides in a high Arctic environment. Nat Commun 10.

López-Blanco E, Lund M, Christensen TR, Tamstorf MP, Smallman TL, Slevin D, Westergaard-Nielsen A, Hansen BU, Abermann J, Williams M. 2018. Plant traits are key determinants in buffering the meteorological sensitivity of net carbon exchanges of Arctic tundra. J Geophys Res-Biogeosci 123:2675–94.

López-Blanco E, Lund M, Williams M, Tamstorf MP, Westergaard-Nielsen A, Exbrayat JF, Hansen BU, Christensen TR. 2017. Exchange of CO2 in Arctic tundra: impacts of meteorological variations and biological disturbance. Biogeosciences 14:4467–83.

Lund M, Hansen BU, Pedersen SH, Stiegler C, Tamstorf MP. 2014. Characteristics of summer-time energy exchange in a high Arctic tundra heath 2000–2010. Tellus Ser B-Chem Phys Meteorol 66.

Lund M, Stiegler C, Abermann J, Citterio M, Hansen BU, van As D. 2017a. Spatiotemporal variability in surface energy balance across tundra, snow and ice in Greenland. Ambio 46:S81–93.

Lund M, Christensen TR, Lindroth A, Schubert P. 2012a. Effects of drought conditions on the carbon dioxide dynamics in a temperate peatland. Environ Res Lett 7:045704.

Lund M, Falk JM, Friborg T, Mbufong HN, Sigsgaard C, Soegaard H, Tamstorf MP. 2012b. Trends in CO2 exchange in a high Arctic tundra heath, 2000–2010. J Geophys Res: Biogeosci 117:G02001.

Lund M, Raundrup K, Westergaard-Nielsen A, López-Blanco E, Nymand J, Aastrup P. 2017b. Larval outbreaks in West Greenland: instant and subsequent effects on tundra ecosystem productivity and CO2 exchange. Ambio 46:26–38.

Mastepanov M, Sigsgaard C, Tagesson T, Strom L, Tamstorf MP, Lund M, Christensen TR. 2013. Revisiting factors controlling methane emissions from high-Arctic tundra. Biogeosciences 10:5139–58.

Myers-Smith IH, Forbes BC, Wilmking M, Hallinger M, Lantz T, Blok D, Tape KD, Macias-Fauria M, Sass-Klaassen U, Lévesque E, Boudreau S, Ropars P, Hermanutz L, Trant A, Collier LS, Weijers S, Rozema J, Rayback SA, Schmidt NM, Schaepman-Strub G, Wipf S, Rixen C, Ménard CB, Venn S, Goetz S, Andreu-Hayles L, Elmendorf S, Ravolainen V, Welker J, Grogan P, Epstein HE, Hik DS. 2011. Shrub expansion in tundra ecosystems: dynamics, impacts and research priorities. Environ Res Lett 6:045509.

Parmentier F-JW, van der Molen MK, van Huissteden J, Karsanaev SA, Kononov AV, Suzdalov DA, Maximov TC, Dolman AJ. 2011. Longer growing seasons do not increase net carbon uptake in the northeastern Siberian tundra. J Geophys Res: Biogeosci 116:G04013.

Peterson BJ, Holmes RM, McClelland JW, Vörösmarty CJ, Lammers RB, Shiklomanov AI, Shiklomanov IA, Rahmstorf S. 2002. Increasing river discharge to the Arctic Ocean. Science 298:2171–3.

Pirk N, Mastepanov M, Parmentier FJW, Lund M, Crill P, Christensen TR. 2016. Calculations of automatic chamber flux measurements of methane and carbon dioxide using short time series of concentrations. Biogeosciences 13:903–12.

Rasch M, Elberling B, Jakobsen BH, Hasholt B. 2000. ‘High-resolution measurements of water discharge, sediment and solute transport in the river Zackenbergelven, Northeast Greenland. Arct Antarct Alp Res 32:336–45.

Romanovsky VE, Drozdov DS, Oberman NG, Malkova GV, Kholodov AL, Marchenko SS, Moskalenko NG, Sergeev DO, Ukraintseva NG, Abramov AA, Gilichinsky DA, Vasiliev AA. 2010. Thermal state of permafrost in Russia. Permafr Periglac Process 21:136–55.

Rysgaard S, Glud RN. 2007. Carbon cycling in Arctic marine ecosystems: case study Young Sound (Meddelelser om Grønland, Bioscience).

Schmidt NM, Reneerkens J, Christensen JH, Olesen M, Roslin T. 2019. An ecosystem-wide reproductive failure with more snow in the Arctic. PLoS Biol 17.

Sejr MK, Stedmon CA, Bendtsen J, Abermann J, Juul-Pedersen T, Mortensen J, Rysgaard S. 2017. Evidence of local and regional freshening of Northeast Greenland coastal waters. Sci Rep 7.

Stendel M, Christensen JH, Petersen D. 2008. Arctic climate and climate change with a focus on Greenland. Adv Ecol Res 40(40):13–43.

Stiegler C, Lund M, Christensen TR, Mastepanov M, Lindroth A. 2016. Two years with extreme and little snowfall: effects on energy partitioning and surface energy exchange in a high-Arctic tundra ecosystem. Cryosphere 10:1395–413.

Stocker TF, Qin D, Plattner GK, Tignor M, Allen SK, Boschung J, Nauels A, Xia Y, Bex V, Midgley PM. 2013. Climate change 2013: The physical science basis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Toreti A, Naveau P, Zampieri M, Schindler A, Scoccimarro E, Xoplaki E, Dijkstra HA, Gualdi S, Luterbacher J. 2013. Projections of global changes in precipitation extremes from coupled model intercomparison project phase 5 models. Geophys Res Lett 40:4887–92.

Turetsky MR, Abbott BW, Jones MC, Anthony KW, Olefeldt D, Schuur EAG, Koven C, McGuire AD, Grosse G, Kuhry P, Hugelius G, Lawrence DM, Gibson C, Sannel ABK. 2019. Permafrost collapse is accelerating carbon release. Nature 569:32–4.

Vihma T. 2014. Effects of Arctic sea ice decline on weather and climate: a review. Surv Geophys 35:1175–214.

Westermann S, Luers J, Langer M, Piel K, Boike J. 2009. The annual surface energy budget of a high-arctic permafrost site on Svalbard, Norway. Cryosphere 3:245–63.

Zhang WX, Jansson PE, Schurgers G, Hollesen J, Lund M, Abermann J, Elberling B. 2018. Process-oriented modeling of a high Arctic tundra ecosystem: long-term carbon budget and ecosystem responses to interannual variations of climate. J Geophys Res-Biogeosci 123:1178–96.

Zhang X, He J, Zhang J, Polyakov I, Gerdes R, Inoue J, Peili W. 2013. Enhanced poleward moisture transport and amplified northern high-latitude wetting trend. Nat Clim Change 3:47–51.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Danish Ministry of Energy, Utilities and Climate and the Government of Greenland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Author Contributions: TRC wrote and edited the manuscript based on initial work by ML, KS and JA. ELB, JS, MS, MJK, KL, MJM and MM contributed with individual data and analyses. All authors contributed to the writing.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Christensen, T.R., Lund, M., Skov, K. et al. Multiple Ecosystem Effects of Extreme Weather Events in the Arctic. Ecosystems 24, 122–136 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-020-00507-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-020-00507-6