Abstract

There is increasing evidence that childhood Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) elevates risk of later depression, but the mechanisms behind this association are unclear. We investigated the relationship between childhood ADHD symptoms and late-adolescent depressive symptoms in a population cohort, and examined whether academic attainment and peer problems mediated this association. ALSPAC (Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children) is an ongoing prospective longitudinal population-based UK cohort that has collected data since September 1990. 2950 individuals with data on parent-reported ADHD symptoms in childhood (7.5 years) and self-reported depressive symptoms in late adolescence (17.5 years) were included in analyses. 2161 individuals with additional data at age 16 years on parent-reported peer problems as an indicator of peer relationships and formal examination results (General Certificate of Secondary Education; GCSE) as an indicator of academic attainment were included in mediation analyses. Childhood ADHD symptoms were associated with higher depressive symptoms (b = 0.49, SE = 0.11, p < 0.001) and an increased odds of clinically significant depressive symptoms in adolescence (OR = 1.27, 95% CI 1.15–1.41, p < 0.001). The association with depressive symptoms was mediated in part by peer problems and academic attainment which accounted for 14.68% and 20.13% of the total effect, respectively. Childhood ADHD is associated with increased risk of later depression. The relationship is mediated in part by peer relationships and academic attainment. This highlights peer relationships and academic attainment as potential targets of depression prevention and intervention in those with ADHD. Future research should investigate which aspects of peer relationships are important in conferring later risk for depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is a leading cause of disability worldwide [1]. The incidence of MDD rises markedly in adolescence and peaks in early adulthood [2, 3]. Depression has a complex aetiology [4] and various psychiatric disorders in childhood have been shown to increase risk of subsequent depression [5]. Clinical long-term follow-up studies of children with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) show substantially elevated rates of subsequent depression in this group [6,7,8,9]. One longitudinal population-based study reported that 50% of those meeting clinical criteria for ADHD in adolescence had MDD or an anxiety disorder at a follow-up assessment (range of 2–11 years) compared to 35% in those without ADHD [10]. As well as being viewed as a diagnostic category, there is good evidence that ADHD behaves as a continuously distributed risk in the general population [11]. Thus, population-based studies are useful for examining longitudinal links between ADHD symptoms and depression. While there is evidence of a prospective relationship between ADHD and depression across development, the reasons for this association are unclear. Further studies are needed to understand how childhood ADHD increases depression risk as this can help to inform interventions to support young people with ADHD. For those with clinical diagnoses of ADHD, treating core ADHD symptoms is important and may reduce concurrent and subsequent depression risk [12]. However, treatment trials showing the long-term benefits of ADHD treatment on depression are lacking. In addition, preliminary evidence shows that those with depression and ADHD may be at higher risk of antidepressant resistance than those with depression alone [13]. Thus, additional factors that contribute to depression outcomes in those with ADHD need consideration, as these could give insight into additional intervention targets.

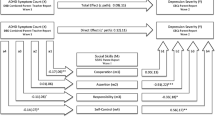

Two possible factors linking ADHD and depression are difficulties in peer relationships and academic attainment. Difficulties with peer relationships have been shown to be important in depression aetiology [14,15,16] and children with ADHD often have difficulties with peers [17, 18]. Academic attainment in examinations and other aspects of educational performance including motivation, the ability to function in the classroom, and general cognitive ability have also been associated with ADHD [19, 20] and depression [16, 21,22,23,24]. A number of theories suggest that the child’s sense of competency or failure with peers and in academic domains is important in conferring later depression risk [25,26,27]. Therefore, difficulties with peer relationships and academic attainment could link ADHD with subsequent depression by acting as mediators (Fig. 1). However, a meta-analytic review of the association between ADHD and depression noted that there are few mechanistic studies [6]. Two studies to date have tested mediation using longitudinal data with time-lags between exposure, mediator, and outcome [28, 29], an important part of testing mediation [30]. One focused on social functioning, social acceptance, and child perceptions of academic functioning as mediators [28]. The other examined peer victimization and asked children who they disliked and who they bullied in their class [29]. The first included 472 participants in a sample selected to over-represent the children of depressed mothers [28]. Mothers completed the ‘attention problems’ subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [31] at age 5 to index childhood ADHD. In a multiple mediator model, a latent variable capturing social functioning and social acceptance mediated the association between attention problems at age 5 and depressive symptoms 15 years later. Although general school functioning as measured by ‘academic stress’ was correlated with attention problems and depressive symptoms in the study, Humphreys and colleagues found that academic stress did not act as a mediator in their multiple mediator model. The second study was conducted in a longitudinal population sample of 728 participants aged approximately 13 at baseline [29]. A peer nomination approach was used where children were asked to report who in their class they disliked and who they bullied. This mediated 7% of the relationship between the CBCL attention problems subscale (a combination of self, parent, and teacher reports) and depression approximately 5 years later. Therefore, these two longitudinal studies examining different potential mediators highlight the need for studies examining additional aspects of peer relationships and the role of academic attainment in the longitudinal relationship of ADHD and depression. More generally, there is a clear need for studies spanning childhood and adolescence to investigate the mechanisms underlying the association between ADHD and depression. In the present study, we tested whether peer relationships and academic attainment mediated the association between childhood ADHD and adolescent depressive symptomology in a large prospective population study spanning 10 years (Fig. 1). We hypothesized that our findings would confirm a prospective association between childhood ADHD symptoms and adolescent depressive symptoms, and show that peer relationships and academic attainment contribute to this association.

Methods

Sample

This sample was derived from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) (https://www.alspac.bris.ac.uk), a large prospective birth cohort in South-West England. Pregnant women in Bristol with a due date between April 1991 and December 1992 were approached to participate. This resulted in 14,541 pregnancies enrolled in the study and 13,988 children alive at 1 year. The children’s development has been followed regularly since birth largely via questionnaires and face-to-face assessments. The methodology and sample are described elsewhere, but the population is generally representative of UK children [32, 33]. Please note that the ALSPAC website contains details of all available data through a searchable data dictionary (https://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/researchers/our-data/). This study is based on a primary sample of 2950 participants for whom data were available on childhood ADHD symptoms, depressive symptoms in late adolescence, and covariates (socioeconomic status, maternal age at birth, sex and childhood emotional problems). Mediation analyses included 2161 participants where data were additionally available on peer problems and academic attainment at 16 years.

Measures

Childhood ADHD symptoms

The main exposure variable was mother-rated DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition) [34] ADHD symptoms at 7 years and 7 months measured with the Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA) [35]. The DAWBA is a well-validated, reliable tool which can be used to derive DSM-IV diagnoses in children and adolescents via computer algorithms and clinical raters. Symptoms of ADHD include inattention, for example “often forgetful in daily activities”, hyperactivity such as “often fidgets with hands or feet”, and impulsivity such as “often interrupts or intrudes on others” that are inconsistent with developmental level, and have been present for 6 months or more, with some symptoms causing impairment in multiple domains before age 7. Symptoms were classed as present if mothers reported them occurring in their child “a little” or “a lot” more than in other children to create a count ranging from 0 to 18. DSM-IV [34] diagnosis of ADHD derived from the DAWBA was used in a sensitivity analysis.

Late-adolescent depression

Continuous and binary depression variables were used as the outcome in this study to give an indication of the impact of ADHD on depressive symptoms and on the odds of reaching a clinical cut-point for depression. For the continuous outcome, ‘depressive symptom score’ was indicated by the self-rated Short Moods and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ) at 17 years and 6 months. The SMFQ is a 13-item questionnaire designed to cover core depressive symptomology with a three-point response scale for each question of ‘Not true’ (0), ‘Somewhat true’ (1), or ‘True’ (2) summed to generate a maximum score of 26 [36]. For the binary outcome, those scoring ≥ 12 on the SMFQ were classed as having ‘clinically significant depressive symptoms’ as recommended previously [37]. The SMFQ is a reliable, valid measure of adolescent depression [37], with high sensitivity and specificity for detecting DSM-IV [38] and ICD-10 [39] MDD diagnoses [40, 41].

Mediator variables

Mediator variables were measured at age 16 years. This ensured a time lag between exposure (age 7.5), mediator (age 16) and outcome (age 17.5) as recommended for mediation analysis [30].

Peer relationships

The 5-item Peer Problem subscale of the mother-completed Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) at 16 years was used [42]. Items such as ‘Teenager has at least one good friend’ and ‘Teenager is generally liked by others’ were rated with responses of ‘Not true’ (2), ‘Sometimes true’ (1), and ‘Certainly true’ (0), with higher scores indicating more peer problems. Items were summed to generate a total score (maximum = 10). The SDQ is a well-validated, reliable behavioural screening tool in young people [42].

Academic attainment

Academic attainment was assessed by performance in formal examinations at the end of secondary school at 16 years (General Certificate of Secondary Education; GCSE examinations). GCSEs are graded from A* (highest grade achievable) to U (lowest grade achievable). A total GCSE and equivalents point score was calculated by summing individual point scores for each GCSE and equivalent qualification grade achieved (A* being equivalent to 58 points, A to 52, B to 46, etc.) [43].

Confounding variables

Analyses were adjusted for mother’s socioeconomic status according to occupation and maternal age at birth to account for sociodemographic factors associated with depression [44]. These were available from mother-reported questionnaires completed during pregnancy or the early years of the study child’s life. Analyses were additionally adjusted for the child’s sex. Sex and sociodemographic variables could potentially confound all three paths between variables tested in the mediation analyses (Fig. 1). Thus, all analyses presented are adjusted for both.

Data analysis

Association between ADHD and depression

Childhood ADHD symptoms were standardised, so that a unit increase was equivalent to a standard deviation unit increase. Linear regression was used to examine the association between standardized childhood ADHD symptoms and continuous depressive symptom score at 17.5 years. Logistic regression was used to examine the association between standardised childhood ADHD symptoms and depression assessed using the binary SMFQ clinical cut-point at 17.5 years. To examine whether sex influenced the association between ADHD symptoms and depression, an interaction term of ADHD symptoms and sex was regressed against depressive symptoms. The Wald test was then used to test whether the model with the interaction term was significantly different to the model without the interaction term. Regressions were also repeated using an exposure variable of ADHD diagnosis.

Mediation by peer relationships and academic attainment

Peer problems and GCSE result scores at 16 years were tested as mediators of the association between childhood ADHD symptoms and adolescent depressive symptoms in two single mediator models. A ‘potential outcomes’ causal mediation framework was used with STATA commands ‘medeff’ and ‘medsens’ [45, 46]. Medeff conducts mediation analyses using Monte Carlo simulation whilst allowing for interaction of exposure and mediator on the outcome. Medsens considers mediation models’ sensitivity to potential confounding by unobserved confounders of the mediator–outcome relationship. This mediation method was selected because the traditional mediation methods can be subject to biases resulting from not considering potential exposure–mediator interaction or unobserved confounding of the mediator–outcome association [47]. Confidence intervals for indirect effects were estimated using a non-parametric bootstrapping approach with 10,000 replications [48]. Reported statistics are Pure Natural Direct Effect (PNDE), Total Natural Indirect Effect (TNIE), and percentage of the total effect that was mediated. PNDE is the direct (unmediated) effect of the exposure on the outcome when the mediator takes the value it would take in the absence of the exposure. TNIE captures the mediated effect of the exposure on the outcome that operates by changing the mediator [49]. In addition, the effect of simultaneously estimating mediation by peer relationships and academic attainment was tested in a multiple mediator model using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) [50]. SEM uses a conceptual model and a series of regression-like equations to capture complex relationships within a network of variables, which is expressed as a path diagram. SEM does not have the ‘potential outcomes’ advantages of considering exposure–mediator interaction or mediator–outcome confounding, but is suited to testing more complex mediation models.

Sensitivity analyses

As previous work has found victimization to mediate the association between ADHD symptoms and subsequent depression [29], we additionally tested whether observations of mediation effects by peer problems were driven by victimisation. To do this, the peer problem mediation analysis was repeated with the item “young person is picked on or bullied by other young people” removed from the Peer Problems score of the SDQ [42].

Three sensitivity tests were conducted to check for the effect of timing of variables. Use of mediator data collected at an earlier time point than depression data does not ensure that these mediators actually preceded depressive symptoms. Thus, mediation analyses were repeated adjusting for depressive symptoms at 14 years (prior to the measurement of mediators) to account for depression occurring earlier in adolescence (Supplement 1). Furthermore, although academic attainment data were not available at an earlier age than 16 years, we repeated the peer relationship mediation analysis using peer problem and depression data collected at earlier time points. We used SDQ peer problems data collected at 9.5 years (prior to the typical age of onset of depression) and SMFQ depressive symptoms at age 13 years (Supplement 2). In addition, we checked whether observed associations between ADHD and adolescent depression were due to ‘pre-existing’ childhood emotional problems occurring approximately contemporaneously with ADHD. This could confound the direct association between ADHD and depressive symptoms. Therefore, emotional problems as indicated by the SDQ emotional problems subscale at 8 years (with a score of ≥ 5 classed as ‘abnormal’) [42] were adjusted for in an additional regression. However, it is possible that childhood emotional problems may be on the causal pathway between ADHD and depression. Therefore, it was not included as a covariate in the fully adjusted regressions.

Missing data

To address the possibility of bias due to non-random missing data, all analyses were repeated with Inverse Probability Weighting (IPW) applied. IPW is a reliable technique for handling missing data, particularly in longitudinal studies where participants can have missing values on multiple variables [51]. Weights were generated based on predictors of missingness from the analysis sample (Supplement 3), as conducted previously in ALSPAC [52]. To investigate predictors of missingness, childhood ADHD symptoms, sex, and sociodemographic variables were individually regressed against missingness from mediator or outcome data (Supplement 4).

Results

In the 2950 participants (1298 males and 1652 females) with complete data, 0.47% (n = 14) met the criteria for DSM-IV ADHD diagnosis at 7.5 years. DSM-IV ADHD symptoms (mean = 3.58, standard deviation = 4.55) were used to define the primary ADHD exposure variable. 17.32% (n = 511) met the clinical cut-point for depression at 17.5 years (mean symptom score = 6.45, standard deviation = 5.18). As expected, the majority of those with ADHD were male (85.71%) and the majority of those reaching the binary cut-point for clinically significant depressive symptoms were female (66.73%). Table 1 shows the correlations of analysis variables.

Association between childhood ADHD and adolescent depression

Standardised childhood ADHD symptoms predicted the continuous outcome of adolescent depressive symptom score (b = 0.49, SE = 0.11, p < 0.001). There was no significant interaction between ADHD symptoms and sex in predicting depressive symptom score (Wald test: F = 0.99, d.f. = (1, 2946), p = 0.32), though the relationship was slightly stronger in females (b = 0.59, SE = 0.17, p < 0.001) than males (b = 0.40, SE = 0.13, p = 0.002).

Childhood ADHD symptoms predicted the binary outcome of clinically significant depressive symptoms at age 17.5 years (OR = 1.27, 95% CI = 1.15–1.41, p < 0.001). This remained the case when adjusting for socioeconomic factors, sex and childhood emotional problems (Table 2). When examining sex differences, there was no significant interaction between ADHD symptoms and sex in predicting clinically significant depressive symptoms (Wald test: X2 = 2.02, d.f. = (1), p = 0.16), though the association was slightly stronger in females (OR = 1.36, 95% CI = 1.18–1.56, p < 0.001) than males (OR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.01–1.37, p = 0.04). Clinical diagnosis of ADHD (n = 14: 12 males and 2 females) was also associated with increased odds of clinically significant depressive symptoms at 17.5 years (OR = 4.49, 95% CI = 1.53–13.19, p = 0.006).

The role of peer relationships and academic attainment in the association between ADHD and depression

Peer relationships at 16 years mediated the association between childhood ADHD symptoms and late-adolescent depressive symptoms, accounting for 14.68% of the total effect (Table 3). Peer problems remained a mediator when the item tapping victimization—“picked on or bullied by other young people”—was removed (Total Natural Indirect Effect: b = 0.07, 95% CI = 0.01–0.14), accounting for 12.50% of the association.

Academic attainment mediated the association between childhood ADHD symptoms and late-adolescent depressive symptoms, accounting for 20.13% of the total effect (Table 3).

When testing peer relationships and academic attainment simultaneously in a multiple mediator SEM model, mediated pathways between ADHD and depressive symptoms via peer relationships and academic attainment revealed a similar pattern of results (Supplement 5).

One of the advantages of the potential outcomes approach to mediation is that it allowed testing of potential unobserved confounding of the mediator–depression relationship. The ‘medsens’ test indicated that the product of observed variance in mediator and outcome that would need to be explained by an unmeasured confounder for mediation effects to disappear ranged from approximately 0.005–0.008 (Supplement 6). To aid interpretation of this coefficient, we compared it with the estimate for a measured confounder—socioeconomic status of mother. The estimate for socioeconomic status of mother on mediation by academic attainment was 0.0002. The coefficient for unobserved confounding required to eliminate the observed mediated effects is, therefore, considerably larger than that present for the measured confounder of socioeconomic status. Thus, it seems unlikely that unobserved confounding would account for the observed results.

Inverse probability weighting (IPW)

Results remained very similar when IPW was applied to analyses. Childhood ADHD symptoms remained associated with the continuous late-adolescent depressive symptom score (b = 0.55, SE = 0.12, p < 0.001) and with the binary measure of clinically significant depressive symptoms in late adolescence (OR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.16–1.44, p < 0.001). Mediation results with IPW applied are shown in Supplement 7.

Discussion

This study investigated the prospective association between childhood ADHD symptoms and late-adolescent depressive symptoms over a 10-year period in a population cohort and evaluated potential mediation by peer relationships and academic attainment. Results confirmed an association between childhood ADHD symptoms and adolescent depressive symptoms in line with previous findings [6,7,8,9,10], supporting a longitudinal relationship between ADHD and depression in the general population.

Mediation results demonstrated that difficulties with peer relationships and academic attainment at 16 years contribute to the pathway from childhood ADHD symptoms to adolescent depressive symptoms as we hypothesized (Fig. 1). This finding is in line with previously proposed models which suggest that young people who struggle in their school and social lives are more likely to experience feelings of failure and rejection, which leave them more vulnerable to depression and emotional problems [26, 27]. The present results help reconcile previous uncertainties in the literature as to whether peer and academic-related factors contribute to the association of ADHD and depression, stemming from a lack of studies investigating longitudinal mediation of this association [6]. Peer problems explained 14.68% of the total effect between ADHD and depressive symptoms. This aligns with previous findings of a latent variable capturing social functioning and social acceptance mediating an association between attention problems (as measured by the attention problems subscale of the CBCL [31]) and depressive symptoms in a sample selected to over-represent the children of depressed mothers [28]. We also show that peer relationships may play an important part in the pathway from ADHD to depression and that this is not driven entirely by the effect of being bullied, which has been evidenced to contribute to the longitudinal association of ADHD and depression [29]. In our study, peer problems still mediated 12.50% of the total effect when the “young person is picked on or bullied by other young people” item of the scale was removed. This highlights that additional aspects of peer relationships such as having good friendships, feeling liked by others, and playing or socialising with others may also be important protective factors for depression in those with ADHD. Indeed, it is important to consider that different aspects of peer relationships may have different effects in those with ADHD, which might impact on the most appropriate choice of target for depression interventions. For instance, there is strong evidence that peer victimisation increases later depression risk [53, 54]. In addition, good quality peer relationships can support young people at elevated familial risk for depression and have been shown to be associated with mental health resilience in this group [55].

Academic attainment also mediated the link between ADHD and depression in our study with GCSE results explaining 20.13% of the association between childhood ADHD and adolescent depressive symptoms. This finding contrasts somewhat with results of a longitudinal mediation study that found that child perceptions of academic stress did not mediate the association of attention problems and depressive symptoms [28]. However, differences between the two studies may account for this. In particular, the academic mediator differed in that the present study assessed academic attainment by performance in formal public examinations (GCSE results), while Humphreys and colleagues used a life stress interview at age 15 to assess perceptions of stress and functioning at school. The current study focused on the two measured mediators of academic attainment and peer relationships, whereas Humphrey’s and colleagues used mediation models comprising of multiple latent variables capturing functioning in various domains. Due to these study differences, it is difficult to make any comparisons of the mediation results. However, it is interesting to consider whether different aspects of school life have distinctive effects in those with elevated ADHD symptoms. While the other study found that general functioning in school was not a mediator of the association of attention problems and depressive symptoms [28], we found that academic attainment (GCSE exam results) mediated the association of ADHD and depressive symptoms. This suggests that academic attainment may be an important target within school life for depression intervention in those with ADHD. Nonetheless, comparison of results from these contrasting study designs should be interpreted with caution.

Those with ADHD may struggle with academic attainment for various reasons, including difficulties with formal classroom learning where sustained attention, self-control, emotion modulation, and adherence to rules are frequently required. In essence, mediation analysis involves specifying a potentially causal sequence where an antecedent influences a mediator which influences an outcome. Thus, although IQ may affect academic attainment [56], we did not test for a possible mediating effect of IQ between childhood ADHD and late-adolescent depression because of the assumptions this would imply about the temporal ordering of variables. We focused on academic attainment as a mediator as it was assessed at a time point between childhood ADHD and late-adolescent depression where it could influence later depression. Academic attainment may also potentially be more amenable to intervention when compared to IQ. Furthermore, the characteristics required for formal classroom learning such as self-control have been shown to predict academic attainment measured by school grades more strongly than IQ [57]. A systematic review of school-based non-pharmacological interventions for ADHD found that the expectations of the classroom were not a good “fit” for those with ADHD, which had a negative impact on academic performance and peer interaction [58]. Repeated infringements of classroom expectations resulting in lowered academic attainment and less positive peer interactions may lead to feelings of failure and isolation, thus increasing risk for developing depression [26, 27]. Overall, our findings suggest that reduced ability to form and maintain friendships and perform well academically may drive part of the development of adolescent depression in those with childhood ADHD in the general population.

It is worth noting that the peer relationships and academic attainment mediators may represent person-effects on the environment, vice versa, or both [59]. As ADHD and depression share genetic liability [60, 61], shared genetic liability with the mediators cannot be ruled out as an explanation of results. Also of note is the observation that young people with ADHD have been found to under-report their depressive symptoms [62], which may lead to an underestimation of associations.

Limitations of this study include the finite number of mediators investigated, although mediators studied were hypothesis-driven. Mediators were tested independently as we elected to use potential-outcome mediation with the ‘medeff’ STATA command, which does not allow simultaneous estimation. The potential-outcome method overcomes limitations of traditional mediation approaches, including consideration of exposure–mediator interaction and unobserved confounding of the mediator-outcome association [47]. However, to check that the results did not differ when testing the mediators simultaneously, we also tested a multiple mediator model using SEM [50]. In this model, mediated pathways via peer relationships and academic attainment were both significant (Supplement 5). Assessment of the mediators at an earlier time point than depressive symptoms does not guarantee that these factors preceded depressive symptoms. However, regressions adjusted for earlier childhood emotional problems showed that childhood ADHD was still associated with depression at 17.5 years (Table 1). Mediation analyses adjusted for depressive symptoms at 14 years—prior to the measurement of peer relationships or academic attainment—also remained very similar (Supplement 1). However, this sensitivity check should be interpreted with caution, as depression at 14 would almost certainly be affected by the exposure and thus act as an intermediate confounder. Furthermore, although academic attainment data were only available at 16 years, we repeated the peer problem mediation analysis using data collected at earlier time points. We found that peer problems at age 9.5 years (prior to the typical age of onset of depression) still mediated the association between ADHD symptoms at age 7.5 years and depressive symptoms at age 13 years, accounting for over 20% of the total relationship (Supplement 2). Attrition is an issue in ALSPAC as with many longitudinal population cohorts [63]. Missingness at 17.5 years was predicted by childhood ADHD symptoms, meaning that those with ADHD may be under-represented. Indeed, ADHD diagnosis prevalence in this study (0.47%) was lower than reported in the UK population of children (1.5%) [64]. However, this would likely result in attenuation of associations if there was an effect on results. Inclusion of variables predicting missingness from depression data (socioeconomic status, maternal age at birth and sex) as confounders in analyses helped address bias that may be caused by missing data [65]. To investigate impact of further bias arising from missing data, we repeated analyses with Inverse Probability Weights applied. Results remained very similar, suggesting that the impact of missing data was minimal (Supplement 7) [51].

This study benefited from longitudinal data spanning 10 years, allowing the mediation of the relationship between ADHD and depression to be investigated across development from childhood to adolescence. Adolescence is an important stage to study due to its association with increased depression levels [2, 3]. Longitudinal data help to avoid potential misclassification of individuals as unaffected by depression that can occur when long-term follow-up to late adolescence is not possible. Longitudinal data allowed time-lags between measurement of exposure, mediator, and outcome—an important part of investigating developmental pathways with mediation analyses [30]. Use of a large prospective population sample avoided the selection bias that can result from including only those at the severe end of the disorder group, as is the case in previous clinical studies [6].

Implications

Due to the increased risk of clinically significant depressive symptoms in children with ADHD, it is important to monitor this group for depression. Monitoring children with ADHD may allow early identification and treatment of depression. ADHD symptoms were associated with depressive symptoms partly via peer relationships (even when accounting for potential effects of bullying) and academic attainment. This indicates that the development of interventions targeting the impact of children’s ADHD on their peer relationships and academic attainment may have the added benefit of reducing depression risk, in addition to treating core ADHD symptoms. For instance, a number of existing psychosocial interventions available for those with ADHD that target social skills and academic skills [66,67,68] may have the potential to reduce depression risk, though this needs to be formally tested.

For future research, a greater understanding of the specific components of peer relationship difficulties in those with ADHD that confer depression risk would allow further insight into the most appropriate targets for intervention.

Conclusions

We show in a longitudinal population cohort that childhood ADHD symptomology is associated with increased risk of clinically significant depressive symptoms in late adolescence. This adds to a growing body of research highlighting the need for depression monitoring in young people with ADHD. We found that the association is mediated in part by peer problems and academic attainment. This highlights these areas as potential targets for depression prevention and intervention in children with ADHD.

References

Vos T, Abajobir AA, Abbafati C et al (2017) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 390:1211–1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O et al (2005) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62:593–602. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

Thapar A, Collishaw S, Pine DS, Thapar AK (2012) Depression in adolescence. Lancet 379:1056–1067. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60871-4

Rice F, Sellers R, Hammerton G et al (2017) Antecedents of new-onset major depressive disorder in children and adolescents at high familial risk. JAMA Psychiatry 74:153–160. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3140

Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE et al (2003) Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60:709–717. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709

Meinzer MC, Pettit JW, Viswesvaran C (2014) The co-occurrence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and unipolar depression in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev 34:595–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.10.002

Chronis-Tuscano A, Molina BSG, Pelham WE et al (2012) Very early predictors of adolescent depression and suicide attempts in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67:1044–1051. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.127

Biederman J, Ball SW, Monuteaux MC et al (2008) New insights into the comorbidity between ADHD and major depression in adolescent and young adult females. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 47:426–434. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816429d3

Gundel LK, Pedersen CB, Munk-Olsen T, Dalsgaard S (2018) Longitudinal association between mental disorders in childhood and subsequent depression: a nationwide prospective cohort study. J Affect Disord 227:56–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.10.023

Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ (2010) Classification of behavior disorders in adolescence: Scaling methods, predictive validity, and gender differences. J Abnorm Psychol 119:699–712. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018610

Thapar A, Cooper M (2016) Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet 387:1240–1250. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00238-X

Chang Z, D’Onofrio BM, Quinn PD et al (2016) Medication for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and risk for depression: a nationwide longitudinal cohort study. Biol Psychiatry 80:916–922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.02.018

Chen M-H, Pan T-L, Hsu J-W et al (2016) Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder comorbidity and antidepressant resistance among patients with major depression: a nationwide longitudinal study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 26:1760–1767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.09.369

Vaananen JM, Marttunen M, Helminen M, Kaltiala-Heino R (2014) Low perceived social support predicts later depression but not social phobia in middle adolescence. Heal Psychol Behav Med 2:1023–1037. https://doi.org/10.4178/epih/e2014037

Goodyer I, Wright C, Altham PME (1989) Recent friendship in anxious and depressed school age children. Psychol Med 19:165–174

Cole DA (1990) Relation of social and academic competence to depressive symptoms in childhood. J Abnorm Psychol 99:422–429

Mikami AM (2010) The importance of friendship for youth with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 13:181–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-010-0067-y.The

Finsaas MC, Kessel EM, Dougherty LR et al (2018) Early childhood psychopathology prospectively predicts social functioning in early adolescence. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 11:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2018.1504298

Birchwood J, Daley D (2012) Brief report: the impact of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) symptoms on academic performance in an adolescent community sample. J Adolesc 35:225–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.08.011

Kessler RC, Adler LA, Berglund P et al (2014) The effects of temporally secondary co-morbid mental disorders on the associations of DSM-IV ADHD with adverse outcomes in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Psychol Med 44:1779–1792. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713002419

Riglin L, Petrides KV, Frederickson N, Rice F (2014) The relationship between emotional problems and subsequent school attainment: a meta-analysis. J Adolesc 37:335–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.02.010

Rahman MA, Todd C, John A et al (2018) School achievement as a predictor of depression and self-harm in adolescence: linked education and health record study. Br J Psychiatry 212:215–221. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2017.69

Riglin L, Collishaw S, Shelton KH et al (2015) Higher cognitive ability buffers stress-related depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. Dev Psychopathol 28:97–109. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579415000310

Glaser B, Gunnell D, Timpson NJ et al (2011) Age- and puberty-dependent association between IQ score in early childhood and depressive symptoms in adolescence. Psychol Med 41:333–343. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291710000814

Cole DA, Martin JM, Powers B (1997) A competency-based model of child depression : a longitudinal study of peer, parent, teacher, and self-evaluations. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38:505–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01537.x

Capaldi DM (1992) Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: II. A 2-year follow-up at grade 8. Dev Psychopathol 4:125–144. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579400005605

Patterson GR, Stoolmiller M (1991) Replications of a dual failure model for boys’ depressed mood. J Consult Clin Psychol 59:491–498

Humphreys KL, Katz SJ, Lee SS et al (2013) The association of ADHD and depression: mediation by peer problems and parent-child difficulties in two complementary samples. J Abnorm Psychol 122:854–867. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033895

Roy A, Hartman CA, Veenstra R, Oldehinkel AJ (2015) Peer dislike and victimisation in pathways from ADHD symptoms to depression. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 24:887–895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0633-9

Selig JP, Preacher KJ (2009) Mediation models for longitudinal data in developmental research. Res Hum Dev 6:144–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427600902911247

Achenbach TM, Ruffle TM (2000) The child behavior checklist and related forms for assessing behavioral/emotional problems and competencies. Pediatr Rev 21:265–271. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.21-8-265

Boyd A, Golding J, Macleod J et al (2013) Cohort profile: the ’children of the 90s’-The index offspring of the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children. Int J Epidemiol 42:111–127. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys064

Fraser A, Macdonald-wallis C, Tilling K et al (2013) Cohort profile: the avon longitudinal study of parents and children: ALSPAC mothers cohort. Int J Epidemiol 42:97–110. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys066

American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington

Goodman R, Ford T, Richards H et al (2000) The development and well-being assessment: description and initial validation of an integrated assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 41:645–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2000.tb02345.x

Angold A, Costello E, Messer S et al (1995) Development of a questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 5:237–249

Thabrew H, Stasiak K, Bavin LM et al (2018) Validation of the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ) and Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ) in New Zealand help-seeking adolescents. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 27:e1610. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1610

American Psychiatric Association (1987) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-III-R). American Psychiatric Association, Washington

World Health Organization (1992) The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders : clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. World Health Organisation, Geneva

Thapar A, McGuffin P (1998) Validity of the shortened Mood and Feelings Questionnaire in a community sample of children and adolescents: a preliminary research note. Psychiatry Res 81:259–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1781(98)00073-0

Turner N, Joinson C, Peters TJ et al (2014) Validity of the short mood and feelings questionnaire in late adolescence. Psychol Assess 26:752–762. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036572

Goodman R (1997) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38:581–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

Department of Education (2010) Test and examination point scores used in the 2010 school and college performance tables. https://education.infotap.uk/schools/performance/archive/schools_10/points.pdf. Accessed 14 Aug 2018.

Gilman SE, Kawachi I, Fitzmaurice GM, Buka SL (2002) Socioeconomic status in childhood and the lifetime risk of major depression. Int J Epidemiol 31:359–367. https://doi.org/10.1093/intjepid/31.2.359

Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D (2010) A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychol Methods 15:309–334. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020761

Hicks R, Tingley D (2011) Causal mediation analysis. Stata J 11:1–15

Richiardi L, Bellocco R, Zugna D (2013) Mediation analysis in epidemiology: methods, interpretation and bias. Int J Epidemiol 42:1511–1519. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt127

Montoya AK, Hayes AF (2017) Two-condition within-participant statistical mediation analysis: a path-analytic framework. Psychol Methods 22:6–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000086

Vanderweele TJ (2014) A unification of mediation and interaction: a four-way decomposition. Epidemiology 25:749–761. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000121

Gunzler D, Chen T, Wu P, Zhang H (2013) Introduction to mediation analysis with structural equation modeling. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry 25:390–394. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2013.06.009

Seaman SR, White IR (2013) Review of inverse probability weighting for dealing with missing data. Stat Methods Med Res 22:278–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280210395740

Anderson EL, Fraser A, Caleyachetty R et al (2018) Associations of adversity in childhood and risk factors for cardiovascular disease in mid-adulthood. Child Abus Negl 76:138–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.10.015

Lima IMM, Peckham AD, Johnson SL (2018) Cognitive deficits in bipolar disorders: Implications for emotion. Clin Psychol Rev 59:126–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.11.006

Bowes L, Joinson C, Wolke D, Lewis G (2015) Peer victimisation during adolescence and its impact on depression in early adulthood: prospective cohort study in the United Kingdom. BMJ Br Med J 350:h2469. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h2469

Collishaw S, Hammerton G, Mahedy L et al (2016) Mental health resilience in the adolescent offspring of parents with depression: a prospective longitudinal study. Lancet Psychiatry 3:49–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00358-2

Finn AS, Kraft MA, West MR et al (2014) Cognitive skills, student achievement tests, and schools. Psychol Sci 25:736–744. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613516008

Duckworth AL, Seligman MEP (2005) Self-Discipline outdoes IQ in predicting academic performance of adolescents. Psychol Sci 16:939–944. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01641.x

Richardson M, Moore DA, Gwernan-Jones R et al (2015) Non-pharmacological interventions for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) delivered in school settings: systematic reviews of quantitative and qualitative research. Health Technol Assess (Rockv) 19:1–470. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta19450

Rutter M, Pickles A, Murray R, Eaves L (2001) Testing hypotheses on specific environmental causal effects on behavior. Psychol Bull 127:291–324. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.127.3.291

Wray NR, Ripke S, Mattheisen M et al (2018) Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat Genet 50:668–681. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0090-3

Demontis D, Walters RK, Martin J et al (2019) Discovery of the first genome-wide significant risk loci for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat Genet 51:63–75. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0269-7

Fraser A, Cooper M, Agha SS et al (2018) The presentation of depression symptoms in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: comparing child and parent reports. Child Adolesc Ment Health 23:243–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12253

Spratt M, Carpenter J, Sterne JAC et al (2010) Strategies for multiple imputation in longitudinal studies. Am J Epidemiol 172:478–487. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwq137

Green H, McGinnity A, Meltzer H et al (2005) Mental health of children and young people in Great Britain, 2004. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Groenwold RHH, Donders ART, Roes KCB et al (2012) Dealing with missing outcome data in randomized trials and observational studies. Am J Epidemiol 175:210–217

Pfiffner LJ, Hinshaw SP, Owens E et al (2014) A two-site randomized clinical trial of integrated psychosocial treatment for ADHD-inattentive type. J Consult Clin Psychol 82:1115–1127. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036887

Haack LM, Villodas M, McBurnett K et al (2017) Parenting as a mechanism of change in psychosocial treatment for youth with ADHD, predominantly inattentive presentation. J Abnorm Child Psychol 45:841–855. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0199-8

Evans SW, Owens JS, Wymbs BT, Ray AR (2018) Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 47:157–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2017.1390757

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a seedcorn grant from the MRC Centre for Neuropsychiatric Genetics and Genomics and an MRC grant (MR/R004609/1). The UK Medical Research Council and Wellcome (Grant number: 102215/2/13/2) and the University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC. A comprehensive list of grants funding is available on the ALSPAC website (https://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/external/documents/grant-acknowledgements.pdf). ALSPAC data for this research were specifically funded by Wellcome Trust and MRC 092731 which funded data collection on depression. The Wellcome Trust supported the authors GH (Grant No.: 209138/Z/17/Z), JM (Grant No.: 106047), LR and AT (Grant No.: 204895/Z/16/Z), and OE (Grant No.: 104408/Z/14/Z). This publication is the work of the authors and Victoria Powell will serve as guarantor for the contents of this paper. We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them, and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists, and nurses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from ALSPAC Law and Ethics Committee and Local Research Ethics Committees. Informed consent for the use of data collected via questionnaires and clinics was obtained from participants following the recommendations of ALSPAC Ethics and Law Committee at the time.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Powell, V., Riglin, L., Hammerton, G. et al. What explains the link between childhood ADHD and adolescent depression? Investigating the role of peer relationships and academic attainment. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 29, 1581–1591 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01463-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01463-w