Abstract

Objectives

Binding of mononuclear leukocytes to hyaluronan cable structures is a well-known pathomechanism in several chronic inflammatory diseases, but has not yet described for chronic oral inflammations. The aim of this study was to evaluate if and how binding of mononuclear leukocytes to pathologic hyaluronan cable structures can be induced in human gingival fibroblasts.

Material and methods

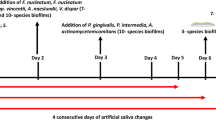

Experiments were performed with human gingival fibroblasts and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from three healthy blood donors. Gingival fibroblasts were stimulated with (1) tunicamycin, (2) polyinosinic/polycytidylic acid (Poly:IC), and (3) lipopolysaccharides (LPS) to simulate (1) ER stress and (2) viral and (3) bacterial infections, respectively. Fibroblasts were then co-incubated with PBMCs, and the number of bound and fluorescently labeled PBMCs was assessed using a fluorescence reader and microscopy. For data analysis, a linear mixed model was used.

Results

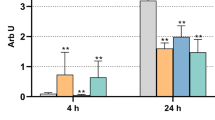

Hyaluronan-mediated binding of PBMCs to gingival fibroblasts was increased by tunicamycin and Poly(I:C) but not by LPS. Hyaluronidase treatment and co-incubation with hyaluronan transport inhibitors reduced this binding.

Conclusions

Results suggest that hyaluronan-mediated binding of blood cells might play a role in oral inflammations. A potential superior role of viruses needs to be confirmed in further clinical studies.

Clinical relevance

The linkage between pathological hyaluronan matrices and oral infections opens up potential applications of hyaluronan transport inhibitors in the treatment of chronic oral inflammations.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bartold PM, Wiebkin OW, Thonard JC (1981) Glycosaminoglycans of human gingival epithelium and connective tissue. Connect Tissue Res 9:99–106. doi:10.3109/03008208109160247

Shibutani T, Imai K, Kanazawa A, Iwayama Y (1998) Use of hyaluronic acid binding protein for detection of hyaluronan in ligature-induced periodontitis tissue. J Periodontal Res 33:265–273. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0765.1998.tb02199.x

Schulz T, Schumacher U, Prehm P (2007) Hyaluronan export by the ABC transporter MRP5 and its modulation by intracellular cGMP. J Biol Chem 282:20999–21004. doi:10.1074/jbc.M700915200

Sorokin L (2010) The impact of the extracellular matrix on inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 10:712–723. doi:10.1038/nri2852

Petrey AC, de la Motte CA (2014) Hyaluronan, a crucial regulator of inflammation. Front Immunol 5:101. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00101

De La Motte CA, Hascall VC, Calabro A et al (1999) Mononuclear leukocytes preferentially bind via CD44 to hyaluronan on human intestinal mucosal smooth muscle cells after virus infection or treatment with poly(I:C). J Biol Chem 274:30747–30755. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.43.30747

Sadowitz B, Seymour K, Gahtan V, Maier KG (2012) The role of hyaluronic acid in atherosclerosis and intimal hyperplasia. J Surg Res 173:e63–e72. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2011.09.025

Young B, Johnson R, Alpers C et al (1995) Cellular events in the evolution of experimental diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 47:935–944. doi:10.1038/ki.1995.139

Selbi W, de la Motte CA, Hascall VC et al (2006) Characterization of hyaluronan cable structure and function in renal proximal tubular epithelial cells. Kidney Int 70:1287–1295. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5001760

Wang A, De La Motte C, Lauer M, Hascall V (2011) Hyaluronan matrices in pathobiological processes. FEBS J 278:1412–1418. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08069.x

Milner CM, Day AJ (2003) TSG-6: a multifunctional protein associated with inflammation. J Cell Sci 116:1863–1873. doi:10.1242/jcs.00407

Rugg MS, Willis AC, Mukhopadhyay D et al (2005) Characterization of complexes formed between TSG-6 and inter-alpha-inhibitor that act as intermediates in the covalent transfer of heavy chains onto hyaluronan. J Biol Chem 280:25674–25686. doi:10.1074/jbc.M501332200

de la Motte CA (2011) Hyaluronan in intestinal homeostasis and inflammation: implications for fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 301:G945–G949. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00063.2011

Majors AK, Austin RC, de la Motte C a, et al (2003) Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces hyaluronan deposition and leukocyte adhesion. J Biol Chem 278:47223–47231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304871200

Xu J, Xiong M, Huang B, Chen H (2015) Advanced Glycation end products upregulate the endoplasmic reticulum stress in human periodontal ligament cells. J Periodontol 86:440–447. doi:10.1902/jop.2014.140446

Lee S-I, Kang K-L, Shin S-I et al (2012) Endoplasmic reticulum stress modulates nicotine-induced extracellular matrix degradation in human periodontal ligament cells. J Periodontal Res 47:299–308. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0765.2011.01432.x

Domon H, Takahashi N, Honda T et al (2009) Up-regulation of the endoplasmic reticulum stress-response in periodontal disease. Clin Chim Acta 401:134–140. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2008.12.007

Yamada H, Nakajima T, Domon H et al (2015) Endoplasmic reticulum stress response and bone loss in experimental periodontitis in mice. J Periodontal Res 50:500–508. doi:10.1111/jre.12232

Zhang K, Kaufman RJ (2008) From endoplasmic-reticulum stress to the inflammatory response. Nature 454:455–462. doi:10.1038/nature07203

Bartold PM (1988) The effect of interleukin-1 beta on hyaluronic acid synthesized by adult human gingival fibroblasts in vitro. J Periodontal Res 23:139–147. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0765.1988.tb01347.x

Bartold PM (1991) Lipopolysaccharide stimulation of hyaluronate synthesis by human gingival fibroblasts in vitro. Arch Oral Biol 36:791–797. doi:10.1016/0003-9969(91)90028-S

Larjava H, Jalkanen M, Penttinen R, Paunio K (1983) Enhanced synthesis of hyaluronic acid by human gingival fibroblasts exposed to human dental bacterial extract. J Periodontal Res 18:31–39. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0765.1983.tb00332.x

Bartold PM, Page RC (1986) The effect of chronic inflammation on gingival connective tissue proteoglycans and hyaluronic acid. J Oral Pathol 15:367–374. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.1986.tb00643.x

Tomakidi P, Fusenig NE, Kohl A, Komposch G (1997) Histomorphological and biochemical differentiation capacity in organotypic co-cultures of primary gingival cells. J Periodontal Res 32:388–400. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0765.1997.tb00549.x

Uehara A, Takada H (2007) Functional TLRs and NODs in human gingival fibroblasts. J Dent Res 86:249–254. doi:10.1177/154405910708600310

Quah BJC, Parish CR (2010) The use of carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) to monitor lymphocyte proliferation. J Vis Exp. doi:10.3791/2259

Stracke D, Schulz T, Prehm P (2011) Inhibitors of hyaluronan export from hops prevent osteoarthritic reactions. Mol Nutr Food Res 55:485–494. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201000210

Prehm P (2013) Curcumin analogue identified as hyaluronan export inhibitor by virtual docking to the ABC transporter MRP5. Food Chem Toxicol 62:76–81. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2013.08.028

Liang K-Y, Zeger SL (1986) Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 73:13–22. doi:10.1093/biomet/73.1.13

Murakami S, Saho T, Asari A et al (1996) CD44-hyaluronate interaction participates in the adherence of T-lymphocytes to gingival fibroblasts. J Dent Res 75:1545–1552. doi:10.1177/00220345960750080501

de la Motte CA, Hascall VC, Drazba J et al (2003) Mononuclear leukocytes bind to specific hyaluronan structures on colon mucosal smooth muscle cells treated with polyinosinic acid:polycytidylic acid: inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor is crucial to structure and function. Am J Pathol 163:121–133. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63636-X

Carcuac O, Berglundh T (2014) Composition of human peri-implantitis and periodontitis lesions. J Dent Res 93:1083–1088. doi:10.1177/0022034514551754

Contreras A, Slots J (2000) Herpesviruses in human periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res 35:3–16. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0765.2000.035001003.x

Hairston BR, Bruce AJ, Rogers RS (2003) Viral diseases of the oral mucosa. Dermatol Clin 21:17–32. doi:10.1016/s0733-8635(02)00056-6

Jiang D, Liang J, Noble PW (2011) Hyaluronan as an immune regulator in human diseases. Physiol Rev 91:221–264. doi:10.1152/physrev.00052.2009

Andrukhov O, Ertlschweiger S, Moritz A et al (2014) Different effects of P. gingivalis LPS and E. coli LPS on the expression of interleukin-6 in human gingival fibroblasts. Acta Odontol Scand 72:337–345. doi:10.3109/00016357.2013.834535

Zhang D, Chen L, Li S et al (2008) Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of Porphyromonas gingivalis induces IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6 production by THP-1 cells in a way different from that of Escherichia coli LPS. Innate Immun 14:99–107. doi:10.1177/1753425907088244

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Aline Saehr and Sandra Foermer for excellent technical assistance and Tess Blundell for English language editing. Special thanks go to Klaus Heeg for providing infrastructure for cell culture experiments in Heidelberg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed this study: DH and PP. Performed experiments: DH. Conceived and designed analysis: DH. Statistical analysis: DH and RK. First draft of manuscript: DH and NM. Contributed and approved the final version of the manuscript: DH, NM, IH, RK, TSK, and PP.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The Medical Faculty of Heidelberg supported this work with a postdoc fellowship for DH.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 129 kb)

ESM 2

(DOCX 140 kb)

Suppl. Fig. 1

Hyaluronan distribution in inflamed and non-inflamed gingival tissue Upper part: Confocal laser scanning microscopy of connective tissue of a patient after conservative periodontal treatment (a) and a patient without periodontal treatment (b). Nuclei stained with HOECHST 33342 (blue). Auto-fluorescence of gingival connective tissue (green). Hyaluronan stained with biotinylated hyaluronan binding protein (red). Lower part: Staining of fibroblast-PBMC co-culture after tunicamycin treatment for 10 minutes (c) and incubation after tunicamycin treatment with 5U hyaluronidase for 10min (d) nuclei (blue), hyaluronan binding protein (green) and CD44 surface marker (red). (JPEG 98 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hagenfeld, D., Mutters, N.T., Harks, I. et al. Hyaluronan-mediated mononuclear leukocyte binding to gingival fibroblasts. Clin Oral Invest 22, 1063–1070 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-017-2188-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-017-2188-x