Abstract

Mood disorders are frequently paralleled by disturbances in circadian rhythm-related physiological and behavioral states and genetic variants of clock genes have been associated with depression. Cryptochrome 2 (Cry2) is one of the core components of the molecular circadian machinery which has been linked to depression, both, in patients suffering from the disease and animal models of the disorder. Despite this circumstantial evidence, a direct causal relationship between Cry2 expression and depression has not been established. Here, a genetic mouse model of Cry2 deficiency (Cry2 −/− mice) was employed to test the direct relevance of Cry2 for depression-like behavior. Augmented anhedonic behavior in the sucrose preference test, without alterations in behavioral despair, was observed in Cry2 −/− mice. The novelty suppressed feeding paradigm revealed reduced hyponeophagia in Cry2 −/− mice compared to wild-type littermates. Given the importance of the amygdala in the regulation of emotion and their relevance for the pathophysiology of depression, potential alterations in diurnal patterns of basolateral amygdala gene expression in Cry2 −/− mice were investigated focusing on core clock genes and neurotrophic factor systems implicated in the pathophysiology of depression. Differential expression of the clock gene Bhlhe40 and the neurotrophic factor Vegfb were found in the beginning of the active (dark) phase in Cry2 −/− compared to wild-type animals. Furthermore, amygdala tissue of Cry2 −/− mice contained lower levels of Bdnf-III. Collectively, these results indicate that Cry2 exerts a critical role in the control of depression-related emotional states and modulates the chronobiological gene expression profile in the mouse amygdala.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cryptochrome 2 (Cry2) is one of the key components of the mammalian intrinsic clock (Griffin et al. 1999; van der Horst et al. 1999; Vitaterna et al. 1999). The genetic core of circadian clocks is constituted of about 20 clock genes, whose expression is regulated by transcriptional and translational feedback loops (Albrecht 2012). In this system, Cry2, together with the clock proteins Cry1, Per1 and Per2, forms a heterodimeric repressor complex which attenuates the Clock/Npas2-Arntl(Bmal1)/Arntl2(Bmal2) activator complex (Gekakis et al. 1998; Kume et al. 1999). In contrast to most core elements of the molecular time keeping system (including Clock, Npas2, Arntl, Arntl2 and the Per proteins), the cryproteins have no Per-ARNT-Sim (PAS) domain (Hsu et al. 1996). However, they have been identified to be required for the maintenance of circadian rhythms. Albeit the fact that absence of either gene alone modulates the period length of the free-running circadian rhythm in opposing directions, the concomitant deletion of both proteins results in a total abolition of free-running rhythmicity (van der Horst et al. 1999).

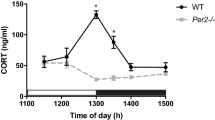

Disturbances in circadian rhythm-related physiological and behavioral states are frequently observed in mood disorders (Carpenter and Bunney 1971; Branchey et al. 1982; von Zerssen et al. 1987; Souetre et al. 1988, 1989; Benca et al. 1992). Interestingly, although the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus constitutes the master organizer of the body’s molecular circadian rhythm, clock genes are also expressed in other regions of the brain, including those relevant to the pathophysiology of depression, such as the amygdala and the hippocampus (Lamont et al. 2005; Jilg et al. 2010; Li et al. 2013; Savalli et al. 2014). Cry2 is highly expressed in the SCN, albeit information on its rhythmic oscillation is controversial (Kume et al. 1999; Mendoza et al. 2005). A diurnal pattern of its expression has been also observed in the amygdala, where it may additionally exert non-circadian functions. Indeed, the observed rhythmic oscillation of Cry2 in the amygdala is disrupted in an animal model of a mood disorder characterized by increased anhedonic behavior following chronic mild stress (Savalli et al. 2014). Furthermore, mice displaying higher trait-anxiety behavior (HAB) and comorbid depression-like behavior (Sah et al. 2012) also express lower levels of Cry2 in the hippocampus as compared to normal anxiety/depression-like behavior (NAB) mice (Griesauer et al. 2014). These observations suggest that altered circadian rhythms and depression-related behavior may be linked at the genetic level. Specifically, they point towards a key role for Cry2, supported by genetic studies in the human population highlighting the association of Cry2 with mood disorders and their depressive episodes (Lavebratt et al. 2010; Sjoholm et al. 2010; Kovanen et al. 2013).

Despite this circumstantial evidence for a role of Cry2 in the pathophysiology of mood disorders, a causal link between altered Cry2 expression and depression-like behavior has not been established so far. The present study aimed at investigating the direct consequences of Cry2-deficiency on depression-like behavior in the mouse and to determine its molecular signature in the basolateral amygdala. Specifically, we investigated whether the lack of Cry2 causes changes diurnal pattern in clock gene expression in amygdala. Additionally, given the critical importance of growth factor support and deficiencies thereof in the pathophysiology of depression, we further aimed to investigate whether Cry2-deficiency affects expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and of the brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which have been both associated to depressive disorders (as reviewed in Yu and Chen 2011; Clark-Raymond and Halaris 2013).

Materials and methods

Male adult Cry2 knock-out (Cry2 −/−) and wild-type littermates (Cry2 +/+) maintained at a C57BL/6J-background (B6.129P2-Cry2 tm1Asn/J) were used (Jackson Laboratory, MA, USA). This strain was created by replacement of the flavine adenine dinucleotide (FAD) binding domain by a neomycin resistance cassette (Thresher et al. 1998; http://jaxmice.jax.org/). Mice were 9–10 weeks old at the onset of experiments. Animals were single-housed in a sound-attenuated room with constant temperature of ≈21 °C under a 12:12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 6:00 a.m.). The light intensity at the level of the animal cages was ≈200 lux. Food and water were freely available throughout the experiment, unless otherwise specified. All experiments were designed to reduce animal suffering and keep the number of animals used at the minimum level. Animal experiments described in this study were approved by the national ethical committee on animal care and use (BMWF-66.009/0302-II/3b/2013; Bundesministerium für Wissenschaft und Forschung) and carried out according to international laws and policies.

Behavioral experiments

All behavioral tests were performed during the light cycle. Mice were habituated to the experimental room 30 min before each test. The same cohort of animals (wild-type, Cry2 +/+ n = 12; Cry2 −/− n = 12) was used in all tests. The order in which tests were performed followed recommendations ranking the tests from least to more stressful (McIlwain et al. 2001) as follows: sucrose preference test, open field, Rota Rod, light/dark box, elevated plus maze, forced swim, tail suspension, novelty-suppressed feeding test. Prior to the initiation of behavioral testing, a gross evaluation of basic neurological function was carried out following an established protocol (Irwin 1968). In agreement with an earlier report (Thresher et al. 1998), no detectable differences in basic neurological performance were observed between Cry2 +/+ and Cry2 −/− mice. A break of at least 24 h was applied between individual tests. All experiments were made by an investigator blind to the genotype of each animal.

Sucrose preference test (SPT)

The SPT was carried out essentially as previously described (Khan et al. 2014). Briefly, prior to testing, mice were habituated to drink a 2 %-sucrose solution, during 4 days of training. On day 1 of the training, mice were deprived of food and water for 18 h. On day 2 and 3, mice were given a 2 %-sucrose solution and food was restored. On day 4, the sucrose solution was replaced with tap water for 6 h. Animals were then deprived of food and water and tested for sucrose preference 18 h later. During the test, subjects were given a free choice between two bottles, one with the sucrose solution and the other with water. Mice were tested over 3 h, starting at 9:00 a.m. To prevent possible effects of side preference in drinking behavior, the position of the bottles (right or left of the feeding compartment) was alternated between animals. Total liquid consumption was measured by weighing the bottles before and after the SPT. Sucrose preference was calculated according to the formula: percentage of preference = (sucrose intake/total intake) × 100.

Novelty-suppressed feeding test (NSF)

The NSF test measures the latency(s) of the subject to the first feeding event in a novel environment. It was performed essentially as described by Mineur et al. (2007) with minor modifications. The testing apparatus consisted of a clear Plexiglas arena (33 × 47 × 17 cm), brightly lit (800 lux). At the beginning of the experiment, each subject was placed in the corner of the novel arena with a food pellet positioned in the center and the latency to the first bite of food was recorded (maximum time 600 s). After the test food consumption in the home cage was evaluated during 5 min.

Forced swim test (FST)

The FST was conducted as previously described (Monje et al. 2011a). Behavior patterns were tracked by VIDEOTRACK (PORSOLT) software provided (Viewpoint, Champagne au mont d’Or, France) during a 6-min session. The last 4 min of the test were used to assess the percentage of time spent immobile.

Tail suspension test (TST)

The TST was conducted as previously described (Monje et al. 2011a), with minor modifications. Mice were securely fastened by the distal end of the tail to a metallic hook in a tail suspension system (MedAssociates, St Albans, VT, USA). The presence or absence of immobility, defined as the absence of limb movement, was tracked over a 6-min session by a computational tracking system (Activity Monitor, MedAssociates, St Albans, VT, USA). Percentage of time spent immobile over the total time was assessed.

Open field (OF)

The OF followed a protocol previously described (Monje et al. 2011a). Briefly, locomotor activity was monitored by a computational tracking system (Activity Monitor, MedAssociates, St Albans, VT, USA). The total distance covered during the 30 min testing time and the time spent in the center zone were evaluated.

Rota Rod test

The Rota Rod test followed a published procedure (Khan et al. 2014). Each mouse was placed separately on one lane of the rotating drum of an automated Rota Rod device (USB Rota Rod ‘SOF-ENV-57X’, MedAssociates, St Albans, VT, USA). The latency to fall off the drum was calculated as the mean value of three consecutive test sessions.

Elevated plus maze (EPM)

The EPM was conducted as previously described elsewhere (Shumyatsky et al. 2002). Briefly, the apparatus consisted of a center platform with adjacent two open and two closed arms. Subjects were placed in the center and their behavior was recorded for 5 min by a computational tracking system (Viewpoint, Champagne au mont d’Or, France). Percentage of time spent in open arms and percentage of number of open arm entries were assessed.

Light/dark box test (LD)

The LD followed a published protocol with minor modifications (Leach et al. 2013). The testing apparatus consisted of a dark and a lit compartment, connected by an opening between the two (MedAssociates, St Albans, VT, USA). Animals were allowed to freely move between the two compartments, and the percentage of time spent in and the number of entries into the lit compartment were measured by a computational tracking system (Activity Monitor, MedAssociates, St Albans, VT, USA) during a 10-min session.

Tissue dissection

Mice of both genotypes were randomly divided into two groups and killed by neck dislocation at Zeitgeber Time (ZT) 0.5 (30 min after lights on), or ZT 12.5 (30 min after lights off). Brains were rapidly removed and immediately frozen at −80 °C. Basolateral amygdala samples were collected using a micro-punch procedure (Lamprecht et al. 2002). Briefly, three adjacent brain coronal sections of 300 μm, from the rostral (Bregma −0.94 mm), medial (Bregma −1.24 mm) and caudal (Bregma −1.54 mm) amygdala (Paxinos and Franklin 2001) were collected. Three bilateral samples of basolateral amygdala were extracted with a blunted 0.69 mm inner diameter sample cannula (Fine Science Tools, Heidelberg, Germany), put into 700 μl Qiazol lysis buffer, vortexed and kept at −80 °C until used for further analysis.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated using a commercially available system [miRNA Micro Kit (Quiagen, CA, USA)], amplified using T-Script® reverse transcriptase (QuantiTect Whole Transcriptome, Quiagen, CA, USA) and quantified by the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Reagent (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The reaction for the subsequent qRT-PCR consisted of 2 μl cDNA sample (out of 25 ng/μl dilution of amplified cDNA reaction) and 5.2 μl RNase-free water, together with 7.8 μl primer-specific master mix containing 7.5 μl Power SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA), 0.15 μl forward primer (20 μM) and 0.15 μl reverse primer (20 μM). The thermal cycling profiles were 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C or 62 °C for 1 min. Transcription levels of target genes were assayed in duplicates and normalized against the amount of β-actin mRNA [delta cycle threshold (dCT)]. β-actin was selected as reference gene as its expression was shown to be stable in mouse amygdala even after emotionally challenging conditions (Stork et al. 2001). Data were plotted using the formula: 2−∆dCT (ddCT), where ddCT is the difference between the mean dCT of each group and the mean dCT of the control group at ZT 0.5. Primers used for amplification of Vegfa, Vegfb, Vegfc, Vegfd, Vegfr-1, Vegfr-2, Vegfr-3 were described previously (Catteau et al. 2011). Primers used for amplification of Bdnf-I, Bdnf-II, Bdnf-III, Bdnf-IV, Bdnf-V, Bdnf (total) were described previously (Tsankova et al. 2006). Primer sequences for all clock genes analyzed [Clock, Bmal1, Cry1, Cry2, CycloB, Dbp, E4bp4, Id2, Npas2, Per1, Per2, Per3, Nr1d1 (Rev-erbα), Nr1d2 (Rev-erbβ), Bhlhe40 (Dec1), Bhlhe41 (Dec2), ROR-α, ROR-β, ROR-γ, NeuroD1] are listed in Supplementary Material.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of behavioral experiments was performed using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Comparisons of gene expression were based on two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (genotype × time point). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction were carried out where significant main effects (p < 0.05) had been revealed by the preceding ANOVA. In each instance, significant outlier calculations were performed based upon the extreme studentized deviate methods using the Grubbs’ test. All data were analyzed using SPSS (IBM, SPSS 18.0) statistical software with the alpha level set at 0.05 at all instances.

Results

Behavioral analysis of Cry2 +/+ and Cry2 −/−

Cry2−/− mice exhibit lower sucrose preference

For the assessment of anhedonic behavior, one of the two core symptoms of depression in humans (DSM-V; American Psychiatric Association 2013), Cry2 −/− mice and wild-type littermates Cry2 +/+ were subjected to the SPT. A significant reduction in the preference for sucrose was found in Cry2 −/− mice; t (20) = 3.80, P < 0.01 (Fig. 1a). No significant differences in body weight were detected between groups [Cry2 +/+ 25.0 ± 0.3 g, Cry2 −/− 24.1 ± 0.6 g; t (22) = 1.33, P > 0.05].

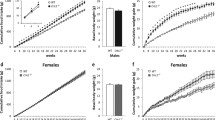

Effect of disruption of the Cry2 gene on anhedonia, hyponeophagia and behavioral despair. In comparison to wild-type littermates (Cry2 +/+), Cry2 −/− mice displayed a lower sucrose preference in the sucrose preference test (SPT) (n = 11 per genotype). In the novelty suppressed feeding (NSF) test Cry2 −/− mice showed b lower latency to food consumption in a novel environment and c unaltered food consumption in the home cage (Cry+/+ n = 11; Cry2 −/− n = 12). Behavioral despair evaluated in d the forced swim test (FST) (n = 12 per genotype) and e tail suspension test (TST) (Cry+/+ n = 12; Cry2 −/− n = 11) was comparable between genotypes. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01

Cry2−/− mice exhibit reduced latency to first feeding event

In order to evaluate depression-related hyponeophagia in Cry2 −/− mice, the NSF (Fig. 1b), a standardized test responsive to chronic, but not acute antidepressant treatment (Bodnoff et al. 1989; Dulawa et al. 2004; Merali et al. 2003), was employed. Reduced hyponeophagia, as reflected in a significant decrease in the time to initiate feeding, was observed in Cry2 −/− compared to Cry2 +/+ animals [t (21) = 0.51, P < 0.05]. No significant differences in home-cage food consumption were detected [t (21) = 2.19, P > 0.05) (Fig. 1c).

Cry2−/− mice demonstrate unaltered behavior in the forced swim test and in the tail suspension test

Cry2 +/+ and Cry2 −/− mice were tested in two standardized paradigms for the assessment of depression-related behavioral despair in rodents, the FST (Fig. 1d) and the TST (Fig. 1e). In both tests, the time spent immobile is used as a parameter indicative of depression-like behavior. No differences between Cry2 +/+ and Cry2 −/− mice were observed in either test.

To control for alterations in locomotor activity or motor coordination potentially confounding the performance in the FST and TST, OF (Fig. 2a, b) analysis and Rota Rod (Fig. 2c) analysis were carried out. No differences between Cry2 −/− and Cry2 +/+ mice were observed in any of the parameters evaluated.

Effect of disruption of the Cry2 gene on locomotion, motor coordination and anxiety-like behavior. Performance of Cry2 −/− in the open field (OF)—a total distance traveled and b time spent in the center zone—and in the Rota Rod c (latency to fall) was comparable to wild-type littermates (Cry2 +/+). No differences in anxiety-like behavior were observed between genotypes in the elevated plus maze (EPM) in d percentage of time spent in open arms and e percentage of open arm entries, or in the light/dark box (LD) in f percentage of time spent in the light zone and g number of entries in the light zone. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 11–12 per genotype)

Cry2−/− mice showed unaltered anxiety-like behavior

To investigate whether the deficiency in Cry2 modulated anxiety-like behavior, Cry2 −/− and Cry2 +/+ mice were subjected to the EPM and the LD tests. No differences in anxiety-like behavior, as represented by percentage of time spent in open arms and the percentage of open arms entries in the EPM test (Fig. 2d, e), and time spent and entries into the light zone in the LD test (Fig. 2f, g) were observed between genotypes.

Diurnal amygdala gene expression profile

Aiming to explore the molecular correlates of the observed behavioral phenotype of Cry2 −/− mice, we focused on gene expression analysis in the basolateral amygdala, critically involved in the regulation of emotional states and related to the pathophysiology of mood disorders (Ressler and Mayberg 2007). Diurnal profiles of clock genes—alterations of which have been previously reported in both depressed patients and animal models of the disease (Li et al. 2013; Savalli et al. 2014)—and neurotrophic and growth factors implicated in the neurobiological alterations of depression were analyzed in Cry2 −/− and Cry2 +/+ mice by qRT-PCR. Mice of both genotypes were randomly divided into two groups and basolateral amygdala samples were collected at two different time points, ZT 0.5 (light) and ZT 12.5 (dark). 20 core clock genes were examined, all of which were found to be expressed in the analyzed samples (Supplementary Table 1a). Two-way ANOVA analysis revealed a statistically significant interaction between genotype and time point [F (1,19) = 5.89; P < 0.05] for basic helix-loop-helix family, member e40 (Bhlhe40) also known as deleted in esophageal cancer 1 (Dec1) (Fig. 3a), without significant main effect. For D site of albumin promoter (albumin D-box) binding protein (Dbp), a significant main effect of time point [F (1,19) = 9.44; P < 0.01; Fig. 3b], without effect of genotype [F (1,19) = 0.58; P > 0.05] or interaction between genotype and time point [F (1,19) = 2.09; P > 0.05], was detected. For nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group D, member 2 (Nr1d2) also known as Rev-erbβ, a significant main effect of time point [F (1,19) = 21.99; P < 0.001; Fig. 3c] was observed, but no significant main effect of genotype [F (1,19) = 0.24; P > 0.05] or interaction between genotype and time point [F (1,19) = 2.38; P > 0.05] was revealed. No statistically significant differences for the other clock genes analyzed were observed (Supplementary Table 1b).

Amygdala clock gene expression in Cry2 −/− and Cry2 +/+ mice at ZT 0.5 and ZT 12.5. Relative gene expression of the clock genes a Bhlhe40, b Dbp and c Nr1d2 determined by qRT-PCR in basolateral amygdala tissue of Cry2 +/+ (white bars) and Cry2 −/− (black bars) mice (n = 5–6 per genotype per condition). Results were normalized to β-actin as reference gene and plotted relative to the mean of the control sample at ZT 0.5. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

qRT-PCR analysis of mRNA levels of molecular elements of growth factor systems highly implicated in the pathophysiology of depression (Yu and Chen 2011; Clark-Raymond and Halaris 2013), namely brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Bdnf), vascular endothelial growth factor (Vegf) and their respective receptors was carried out in basolateral amygdala samples of Cry2 −/− and Cry2 +/+ mice (Supplementary Table 2a). For the individual isoforms of Bdnf, two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time point for Bdnf-I [F (1,19) = 5.61; P < 0.05; Fig. 4a]. No significant main effect of genotype [F (1,19) = 3.86; P > 0.05] or significant genotype by time point interaction [F (1,19) = 0.62; P > 0.05] was observed. A significant main effect of genotype was observed for Bdnf-III [F (1,19) = 4.91; P < 0.05; Fig. 4b]. No significant effect of time point [F (1,19) = 0.35; P > 0.05] or genotype by time point interaction [F (1,19) = 0.91; P > 0.05] was revealed.

Amygdala neurotrophic factor expression in Cry2 −/− mice and Cry2 +/+ at ZT 0.5 and ZT 12.5. Relative gene expression of a Bdnf-I, b Bdnf-III and c Vegfb determined by qRT-PCR in basolateral amygdala tissue of Cry2 +/+ (white bars) and Cry2 −/− (black bars) mice (n = 5–6 per genotype per condition). Results were normalized to β-actin, as reference gene and plotted relative to the mean of the control sample at ZT 0.5. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05

In the case of members of the Vegf family, there was a statistically significant genotype by time point interaction for Vegfb [F (1,19) = 4.97; P < 0.05; Fig. 4c], without significant main effect of either genotype [F (1,19) = 1.02; P > 0.05] or time point [F (1,19) = 0.70; P > 0.05]. No statistically significant differences for the other growth factor genes analyzed were observed (Supplementary Table 2b).

Discussion

The present study firstly assessed the direct consequence of Cry2-deficiency on depression-like behavior and examined its molecular signature in the mouse basolateral amygdala. Behaviorally, increased anhedonic behavior of Cry2 −/− mice was observed in the SPT and reduced hyponeophagia in the NSF test, without alterations in behavioral despair in the FST or TST. Anxiety-like behavior in the EPM or LD tests was not altered in Cry2 −/− mice. Amygdala diurnal gene expression profiling of core clock genes and growth factor systems previously implicated in the pathophysiology of depression revealed that levels of Bhlhe40 were significantly elevated in the beginning of the active (dark) phase in Cry2 −/− mice as compared to wild-type littermates (Cry2 +/+). Moreover, the genotype had a significant effect in that Bdnf-III gene expression was blunted in Cry2 −/− mice and Vegfb levels were significantly reduced in the beginning of the dark phase in Cry2 −/− mice.

Considering that anhedonia is one of the core symptoms of depression in humans and that it is commonly used as indicator of depression-like behavior in animal models (Willner et al. 1992), the observed augmented anhedonic behavior in Cry2−/− mice supports previous observations that link altered expression of Cry2 to depression, both in humans (Lavebratt et al. 2010) and in experimental animals (Griesauer et al. 2014; Savalli et al. 2014). Intact performance of Cry2 −/− mice in the FST and the TST supports previous findings (De Bundel et al. 2013) and suggests that Cry2 may be specifically relevant for the anhedonic endophenotype of depression. Hence, as previously suggested (Lim et al. 2012), the neurobiological aberrations related to anhedonia differ from those mediating the display of despair and support the hypothesis that the diversity of clinical features observed in depressed patients may indeed be subserved by distinct underlying molecular mechanisms. Interestingly, while no differences in baseline anxiety-like behavior were detected in the EPM, the LD and the OF, the significantly reduced latency to feed in Cry2 −/− mice in the NSF is indicative of reduced hyponeophagia which has been associated with depression-related anxiety. In a different strain of Cry2 −/− mice, altered performance in the EPM, which was not corroborated by an additional test assessing anxiety-like behavior, has been reported (De Bundel et al. 2013), and differences to our observations in three independent paradigms testing baseline anxiety-like behavior might relate to the specific mouse line used or variations in the individual experimental set-ups.

While seemingly opposing the result in the SPT, the intriguing observation in the NSF, however, suggests that Cry2 may be involved in or modulate some of the signaling cascades activated by chronic antidepressant drug treatment which is known to induce a decreased latency to feed in the NSF (Dulawa et al. 2004; Mineur et al. 2009; Warner-Schmidt et al. 2011).

The NSF test is unique among the plethora of tests available to evaluate anxiety-like and depression-related behaviors in mice. In comparison to “classical” assays monitoring anxiety-like behavior, such as the EPM and the LD, it comprises the additional aspect of motivation, since through the component to food-deprivation the animal is experiencing a conflict situation in which the innate avoidance for open novel areas has to be reconciled with the incentive to consume food. On the other hand, the SPT also evaluates the ability to seek pleasure from the rewarding experience of energy consumption, which is in the SPT evaluated in the familiar, hence experienced as “safe”, home cage environment. The NSF introduces the elicitation of endogenous fear through the perception of novel, anxiogenic spaces, as added variable. This characteristic set of test-specific demands may explain the distinctive position of the NSF with regard to its potential to selectively reveal behavioral effects of chronic antidepressant treatment. Hence, considering the results of reduced latency to feed in the NSF, it is tempting to speculate that Cry2 −/− mice might be more sensitive to the effects of antidepressant treatments, despite or even because of their augmented depression-related anhedonia displayed in the NSF. However, this interesting hypothesis warrants further experimental evidence through the assessment of the behavioral and cellular effects of chronic administration of antidepressant drugs in a novel cohort of Cry2-deficient mice and wild-type littermates.

Of note, in a mouse model of an anxiety/depression-like state induced by chronic corticosterone treatment, chronic antidepressant treatment has been shown to differentially affect depression-like behavior in specific tests, including the NSF, in a hippocampal neurogenesis-dependent manner. Hence, a particular involvement of Cry2 in the neurogenesis-dependent molecular pathways stimulated by chronic antidepressant treatment can be speculated to exist (David et al. 2009). Moreover, one remarkable feature of the Cry proteins is that they oppose glucocorticoid receptor activation and that their deficiency doubles the number of dexamethasone-induced genes in primary fibroblasts from Cry double-knockout mice (Lamia et al. 2011). A critical balance between Cry proteins is required for proper clock functioning (van der Horst et al. 1999). Of the two Cry proteins, Cry2 has a key role in balancing Cry expression, since it not only acts as a general repressor, but also opposes in specific actions of Cry1, denying Cry1 from accessing to DNA targets too early (Anand et al. 2013). Earlier, altered regulation (down-regulation) of glucocorticoid-responsive genes in the basolateral amygdala (Monje et al. 2011b) and selective deletion of the forebrain type II glucocorticoid receptor (Solomon et al. 2012) have been linked to increased depression-like behavior in mice. Cry double-knockout mice display constitutively high levels of circulating corticosterone, suggesting that suppression of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis is reduced and glucocorticoid transactivation in the liver is enhanced (Lamia et al. 2011). On the other hand, mice over-expressing the cerebral glucocorticoid receptor are less susceptible to display depression-like behavior (Schulte-Herbruggen et al. 2006). They have constitutively high levels of Bdnf protein in the hippocampus and higher levels of Bdnf protein in the amygdala, especially during the first hour of the passive (light) phase, when corticosteroid levels are low (Schulte-Herbruggen et al. 2006). In agreement, we found herein that Cry2-deficiency caused constitutively low levels of Bdnf-III mRNA in the basolateral amygdala.

It is known that Bdnf stimulates Vegfb gene expression (Takeda et al. 2005) and that Vegfb in turn stimulates neurogenesis in adult mice (Sun et al. 2006). It seems that Bhlhe40 plays a role in these cascades (Rossner et al. 1997), but it is not known which specific Bdnf isoform is modulated. We here found that levels of Vegfb mRNA in the basolateral amygdala were reduced in the beginning of the active (dark) phase, suggesting a reciprocal relationship between Bhlhe40 and Vegfb in Cry2 −/− mice. Intriguingly, Bhlhe40, Dbp and Nr1d2 are among the top-ranked genes that are rhythmically expressed in the human brain, and individuals with major depressive disorder appear to have lost the alignment between Bhlhe40 and Per2 expression timetables in six brain regions, e.g. in the amygdala (Li et al. 2013).

Another interesting feature of Cry proteins is that they are the actual repressors of the feedback loops in the core of circadian clocks (Dardente et al. 2007; Ye et al. 2011). In addition to their actions in the cell nucleus, Cry proteins act as inhibitors of adenylyl cyclase, thereby limiting cyclic adenosine monophosphate production (Narasimamurthy et al. 2012) and inhibiting the G protein coupled receptor activity through a direct interaction with the G(s)alpha subunit (Zhang et al. 2010). By these mechanisms of action, as we hypothesize here, Cry proteins might protect the individual from a depression-like state seen in conditions where dysfunction in control of the mesolimbic dopaminergic tracts leads to increased cyclic adenosine monophosphate production and increased depression-like behavior (Park et al. 2005).

However, since our observations are based upon a “conventional” knock-out mouse model, we cannot rule out that compensatory changes induced by Cry2-deficiency during development may contribute to the observed behavioral and molecular phenotype of Cry2 −/− mice. Moreover, since Cry2-deletion in this mouse line is not restricted to the hippocampus, the absence of Cry2 may impact on other physiological activities which could in turn modulate the herein studied brain functions and molecular processes. Furthermore, since here gene expression was evaluated in tissue derived from animals under light-entrained circadian rhythms, the specific relevance of Cry2 for the behavioral and molecular functions evaluated under free-running conditions needs to be addressed in future studies.

In conclusion, the present study provides evidence that deletion of Cry2 is associated with depression-like behavior, namely the sucrose preference test, selectively impinging on the anhedonic endophenotype of depression in the mouse. The distinct behavioral display was associated with a modulation of the diurnal pattern of expression of specific clock genes and growth factors in the basolateral amygdala of Cry2 −/− mice.

On the basis of these data, we propose that Cry2 exerts a role in the control of emotional states by participating in amygdala functioning, acting on molecular elements of both the endogenous clock machinery and the network of neurotrophic support.

References

Albrecht U (2012) Timing to perfection: the biology of central and peripheral circadian clocks. Neuron 74(2):246–260

American Psychiatric Association (2013) DSM-V: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Arlington

Anand SN, Maywood ES, Chesham JE, Joynson G, Banks GT, Hastings MH, Nolan PM (2013) Distinct and separable roles for endogenous CRY1 and CRY2 within the circadian molecular clockwork of the suprachiasmatic nucleus, as revealed by the Fbxl3(Afh) mutation. J Neurosci: Off J Soc Neurosci 33(17):7145–7153

Benca RM, Obermeyer WH, Thisted RA, Gillin JC (1992) Sleep and psychiatric disorders. A meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 49(8):651–668 (discussion 669–670)

Bodnoff SR, Suranyi-Cadotte B, Quirion R, Meaney MJ (1989) A comparison of the effects of diazepam versus several typical and atypical anti-depressant drugs in an animal model of anxiety. Psychopharmacology 97(2):277–279

Branchey L, Weinberg U, Branchey M, Linkowski P, Mendlewicz J (1982) Simultaneous study of 24-hour patterns of melatonin and cortisol secretion in depressed patients. Neuropsychobiology 8(5):225–232

Carpenter WT Jr, Bunney WE Jr (1971) Adrenal cortical activity in depressive illness. Am J Psychiatry 128(1):31–40

Catteau J, Gernet JI, Marret S, Legros H, Gressens P, Leroux P, Laudenbach V (2011) Effects of antenatal uteroplacental hypoperfusion on neonatal microvascularisation and excitotoxin sensitivity in mice. Pediatr Res 70(3):229–235

Clark-Raymond A, Halaris A (2013) VEGF and depression: a comprehensive assessment of clinical data. J Psychiatr Res 47(8):1080–1087

Dardente H, Fortier EE, Martineau V, Cermakian N (2007) Cryptochromes impair phosphorylation of transcriptional activators in the clock: a general mechanism for circadian repression. Biochem J 402(3):525–536

David DJ, Samuels BA, Rainer Q, Wang JW, Marsteller D, Mendez I, Drew M, Craig DA, Guiard BP, Guilloux JP, Artymyshyn RP, Gardier AM, Gerald C, Antonijevic IA, Leonardo ED, Hen R (2009) Neurogenesis-dependent and -independent effects of fluoxetine in an animal model of anxiety/depression. Neuron 62(4):479–493

De Bundel D, Gangarossa G, Biever A, Bonnefont X, Valjent E (2013) Cognitive dysfunction, elevated anxiety, and reduced cocaine response in circadian clock-deficient cryptochrome knockout mice. Front Behav Neurosci 7:152

Dulawa SC, Holick KA, Gundersen B, Hen R (2004) Effects of chronic fluoxetine in animal models of anxiety and depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 29(7):1321–1330

Gekakis N, Staknis D, Nguyen HB, Davis FC, Wilsbacher LD, King DP, Takahashi JS, Weitz CJ (1998) Role of the CLOCK protein in the mammalian circadian mechanism. Science 280(5369):1564–1569

Griesauer I, Diao W, Ronovsky M, Elbau I, Sartori S, Singewald N, Pollak DD (2014) Circadian abnormalities in a mouse model of high trait anxiety and depression. Ann Med 46(3):148–154

Griffin EA Jr, Staknis D, Weitz CJ (1999) Light-independent role of CRY1 and CRY2 in the mammalian circadian clock. Science 286(5440):768–771

Hsu DS, Zhao X, Zhao S, Kazantsev A, Wang RP, Todo T, Wei YF, Sancar A (1996) Putative human blue-light photoreceptors hCRY1 and hCRY2 are flavoproteins. Biochemistry 35(44):13871–13877

Irwin S (1968) Comprehensive observational assessment: Ia. A systematic, quantitative procedure for assessing the behavioral and physiologic state of the mouse. Psychopharmacologia 13(3):222–257

Jilg A, Lesny S, Peruzki N, Schwegler H, Selbach O, Dehghani F, Stehle JH (2010) Temporal dynamics of mouse hippocampal clock gene expression support memory processing. Hippocampus 20(3):377–388

Khan D, Fernando P, Cicvaric A, Berger A, Pollak A, Monje FJ, Pollak DD (2014) Long-term effects of maternal immune activation on depression-like behavior in the mouse. Transl Psychiatry 4:e363

Kovanen L, Kaunisto M, Donner K, Saarikoski ST, Partonen T (2013) CRY2 genetic variants associate with dysthymia. PLoS One 8(8):e71450

Kume K, Zylka MJ, Sriram S, Shearman LP, Weaver DR, Jin X, Maywood ES, Hastings MH, Reppert SM (1999) mCRY1 and mCRY2 are essential components of the negative limb of the circadian clock feedback loop. Cell 98(2):193–205

Lamia KA, Papp SJ, Yu RT, Barish GD, Uhlenhaut NH, Jonker JW, Downes M, Evans RM (2011) Cryptochromes mediate rhythmic repression of the glucocorticoid receptor. Nature 480(7378):552–556

Lamont EW, Robinson B, Stewart J, Amir S (2005) The central and basolateral nuclei of the amygdala exhibit opposite diurnal rhythms of expression of the clock protein Period2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102(11):4180–4184

Lamprecht R, Farb CR, LeDoux JE (2002) Fear memory formation involves p190 RhoGAP and ROCK proteins through a GRB2-mediated complex. Neuron 36(4):727–738

Lavebratt C, Sjoholm LK, Soronen P, Paunio T, Vawter MP, Bunney WE, Adolfsson R, Forsell Y, Wu JC, Kelsoe JR, Partonen T, Schalling M (2010) CRY2 is associated with depression. PLoS One 5(2):e9407

Leach G, Adidharma W, Yan L (2013) Depression-like responses induced by daytime light deficiency in the diurnal grass rat (Arvicanthis niloticus). PLoS One 8(2):e57115

Li JZ, Bunney BG, Meng F, Hagenauer MH, Walsh DM, Vawter MP, Evans SJ, Choudary PV, Cartagena P, Barchas JD, Schatzberg AF, Jones EG, Myers RM, Watson SJ Jr, Akil H, Bunney WE (2013) Circadian patterns of gene expression in the human brain and disruption in major depressive disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110(24):9950–9955

Lim BK, Huang KW, Grueter BA, Rothwell PE, Malenka RC (2012) Anhedonia requires MC4R-mediated synaptic adaptations in nucleus accumbens. Nature 487(7406):183–189

McIlwain KL, Merriweather MY, Yuva-Paylor LA, Paylor R (2001) The use of behavioral test batteries: effects of training history. Physiol Behav 73(5):705–717

Mendoza J, Graff C, Dardente H, Pevet P, Challet E (2005) Feeding cues alter clock gene oscillations and photic responses in the suprachiasmatic nuclei of mice exposed to a light/dark cycle. J Neurosci: Off J Soc Neurosci 25(6):1514–1522

Merali Z, Levac C, Anisman H (2003) Validation of a simple, ethologically relevant paradigm for assessing anxiety in mice. Biol Psychiatry 54(5):552–565

Mineur YS, Picciotto MR, Sanacora G (2007) Antidepressant-like effects of ceftriaxone in male C57BL/6J mice. Biol Psychiatry 61(2):250–252

Mineur YS, Eibl C, Young G, Kochevar C, Papke RL, Gundisch D, Picciotto MR (2009) Cytisine-based nicotinic partial agonists as novel antidepressant compounds. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 329(1):377–386

Monje FJ, Cabatic M, Divisch I, Kim EJ, Herkner KR, Binder BR, Pollak DD (2011a) Constant darkness induces IL-6-dependent depression-like behavior through the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. J Neurosci: Off J Soc Neurosci 31(25):9075–9083

Monje FJ, Kim EJ, Cabatic M, Lubec G, Herkner KR, Pollak DD (2011b) A role for glucocorticoid-signaling in depression-like behavior of gastrin-releasing peptide receptor knock-out mice. Ann Med 43(5):389–402

Narasimamurthy R, Hatori M, Nayak SK, Liu F, Panda S, Verma IM (2012) Circadian clock protein cryptochrome regulates the expression of proinflammatory cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109(31):12662–12667

Park SK, Nguyen MD, Fischer A, Luke MP, Affar el B, Dieffenbach PB, Tseng HC, Shi Y, Tsai LH (2005) Par-4 links dopamine signaling and depression. Cell 122(2):275–287

Paxinos G, Franklin K (2001) The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates, 2nd edn. Elsevier Academic Press, USA

Ressler KJ, Mayberg HS (2007) Targeting abnormal neural circuits in mood and anxiety disorders: from the laboratory to the clinic. Nat Neurosci 10(9):1116–1124

Rossner MJ, Dorr J, Gass P, Schwab MH, Nave KA (1997) SHARPs: mammalian enhancer-of-split- and hairy-related proteins coupled to neuronal stimulation. Mol Cell Neurosci 10(3–4):460–475

Sah A, Schmuckermair C, Sartori SB, Gaburro S, Kandasamy M, Irschick R, Klimaschewski L, Landgraf R, Aigner L, Singewald N (2012) Anxiety-rather than depression-like behavior is associated with adult neurogenesis in a female mouse model of higher trait anxiety-and comorbid depression-like behavior. Transl Psychiatry 2:e171

Savalli G, Diao W, Schulz S, Todtova K, Pollak DD (2014) Diurnal oscillation of amygdala clock gene expression and loss of synchrony in a mouse model of depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 18(5). doi:10.1093/ijnp/pyu095

Schulte-Herbruggen O, Chourbaji S, Ridder S, Brandwein C, Gass P, Hortnagl H, Hellweg R (2006) Stress-resistant mice overexpressing glucocorticoid receptors display enhanced BDNF in the amygdala and hippocampus with unchanged NGF and serotonergic function. Psychoneuroendocrinology 31(10):1266–1277

Shumyatsky GP, Tsvetkov E, Malleret G, Vronskaya S, Hatton M, Hampton L, Battey JF, Dulac C, Kandel ER, Bolshakov VY (2002) Identification of a signaling network in lateral nucleus of amygdala important for inhibiting memory specifically related to learned fear. Cell 111(6):905–918

Sjoholm LK, Backlund L, Cheteh EH, Ek IR, Frisen L, Schalling M, Osby U, Lavebratt C, Nikamo P (2010) CRY2 is associated with rapid cycling in bipolar disorder patients. PLoS One 5(9):e12632

Solomon MB, Furay AR, Jones K, Packard AE, Packard BA, Wulsin AC, Herman JP (2012) Deletion of forebrain glucocorticoid receptors impairs neuroendocrine stress responses and induces depression-like behavior in males but not females. Neuroscience 203:135–143

Souetre E, Salvati E, Wehr TA, Sack DA, Krebs B, Darcourt G (1988) Twenty-four-hour profiles of body temperature and plasma TSH in bipolar patients during depression and during remission and in normal control subjects. Am J Psychiatry 145(9):1133–1137

Souetre E, Salvati E, Belugou JL, Pringuey D, Candito M, Krebs B, Ardisson JL, Darcourt G (1989) Circadian rhythms in depression and recovery: evidence for blunted amplitude as the main chronobiological abnormality. Psychiatry Res 28(3):263–278

Stork O, Stork S, Pape HC, Obata K (2001) Identification of genes expressed in the amygdala during the formation of fear memory. Learn Mem 8(4):209–219

Sun Y, Jin K, Childs JT, Xie L, Mao XO, Greenberg DA (2006) Vascular endothelial growth factor-B (VEGFB) stimulates neurogenesis: evidence from knockout mice and growth factor administration. Dev Biol 289(2):329–335

Takeda K, Shiba H, Mizuno N, Hasegawa N, Mouri Y, Hirachi A, Yoshino H, Kawaguchi H, Kurihara H (2005) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor enhances periodontal tissue regeneration. Tissue Eng 11(9–10):1618–1629

Thresher RJ, Vitaterna MH, Miyamoto Y, Kazantsev A, Hsu DS, Petit C, Selby CP, Dawut L, Smithies O, Takahashi JS, Sancar A (1998) Role of mouse cryptochrome blue-light photoreceptor in circadian photoresponses. Science 282(5393):1490–1494

Tsankova NM, Berton O, Renthal W, Kumar A, Neve RL, Nestler EJ (2006) Sustained hippocampal chromatin regulation in a mouse model of depression and antidepressant action. Nat Neurosci 9(4):519–525

van der Horst GT, Muijtjens M, Kobayashi K, Takano R, Kanno S, Takao M, de Wit J, Verkerk A, Eker AP, van Leenen D, Buijs R, Bootsma D, Hoeijmakers JH, Yasui A (1999) Mammalian Cry1 and Cry2 are essential for maintenance of circadian rhythms. Nature 398(6728):627–630

Vitaterna MH, Selby CP, Todo T, Niwa H, Thompson C, Fruechte EM, Hitomi K, Thresher RJ, Ishikawa T, Miyazaki J, Takahashi JS, Sancar A (1999) Differential regulation of mammalian period genes and circadian rhythmicity by cryptochromes 1 and 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96(21):12114–12119

von Zerssen D, Doerr P, Emrich HM, Lund R, Pirke KM (1987) Diurnal variation of mood and the cortisol rhythm in depression and normal states of mind. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci 237(1):36–45

Warner-Schmidt JL, Vanover KE, Chen EY, Marshall JJ, Greengard P (2011) Antidepressant effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are attenuated by antiinflammatory drugs in mice and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(22):9262–9267

Willner P, Muscat R, Papp M (1992) Chronic mild stress-induced anhedonia: a realistic animal model of depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 16(4):525–534

Ye R, Selby CP, Ozturk N, Annayev Y, Sancar A (2011) Biochemical analysis of the canonical model for the mammalian circadian clock. J Biol Chem 286(29):25891–25902

Yu H, Chen ZY (2011) The role of BDNF in depression on the basis of its location in the neural circuitry. Acta Pharmacol Sin 32(1):3–11

Zhang EE, Liu Y, Dentin R, Pongsawakul PY, Liu AC, Hirota T, Nusinow DA, Sun X, Landais S, Kodama Y, Brenner DA, Montminy M, Kay SA (2010) Cryptochrome mediates circadian regulation of cAMP signaling and hepatic gluconeogenesis. Nat Med 16(10):1152–1156

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant of the Austrian Science Fund (stand-alone project P22424) to Daniela D. Pollak.

Conflict of interest

Timo Partonen is receiving speaker’s fees from Finnish Student Health Service, Helsingin Energia, Helsinki Fair, H. Lundbeck, MCD-Team, MERCURIA Business College, Servier Finland and royalties from Duodecim Medical Publications (Oxford University Press).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Handling Editor: N. Singewald.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Savalli, G., Diao, W., Berger, S. et al. Anhedonic behavior in cryptochrome 2-deficient mice is paralleled by altered diurnal patterns of amygdala gene expression. Amino Acids 47, 1367–1377 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-015-1968-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-015-1968-3