Abstract

Aims

Liver steatosis, a typical finding in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), can lead to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. The aim of the present study is to estimate the awareness of liver disease among patients with T2D and whether it differs according to the degree of liver fibrosis estimated by transient elastography (TE).

Methods

This is a population-based cross-sectional study. We included all patients with T2D that participated in the 2017–2018 cycle of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and underwent a TE examination. Presence of liver steatosis and fibrosis was assessed by the median values of controlled attenuation parameter and liver stiffness measurement, respectively.

Results

Among the 825 patients included in the analysis, 8.1% (95% CI 5.1%-12.7%) of patients with steatosis were aware of having a liver condition. Even if awareness increased proportionally with increasing severity of organ damage, it remained limited even among patients with advanced fibrosis (17.9%, 95% CI 8.8%-33.3%).

Conclusions

Despite increasing evidence of a frequent hepatic involvement associated with poor prognosis, awareness of suffering of advanced liver disease in patients with T2D is remarkably low, likely reflecting little recognition also among the team of health care professionals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) are at higher risk of dying from liver-related conditions compared to the general population. While excess risk may be present for viral and alcohol-related hepatic diseases, most of it is attributable to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [1]. NAFLD affects 60–70% of patients with T2D, who are also at higher risk of progression toward nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [2, 3].

Nonetheless, due to many uncertainties, including incomplete information on the natural history of the disease, challenges in the diagnosis of NASH, and few pharmacological agents with proven efficacy, previous studies in the general NAFLD population reported low awareness of this condition among affected individuals [4].

Here, we analyzed data from the 2017–2018 cycle of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to estimate the awareness of liver disease among patients with T2D according to the degree of liver fibrosis, estimated by transient elastography (TE).

Materials and methods

This is an analysis of data from the 2017–2018 cycle of NHANES, a cross-sectional survey program conducted in the US and aimed at including individuals representative of the general, non-institutionalized population of all ages. The survey consists of a structured interview conducted in the home, followed by a standardized health examination that includes a physical examination as well as laboratory tests. The original survey was approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Research Ethics Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from all adult participants.

The present study focuses on adult patients (age ≥ 20 years) with T2D and reliable TE results. Diagnosis of T2D was based on a prior self-reported diagnosis of diabetes and/or a Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level ≥ 48 mmol/mol, with the exclusion of patients with probable type 1 diabetes (age at diagnosis < 30 years and insulin as the only anti-hyperglycemic drug) [5]. In the 2017–2018 cycle, TE was performed by NHANES technicians after a 2-day training program with an expert technician, using the FibroScan® model 502 V2 Touch (Echosens, Paris, France). Exams were considered reliable only if at least 10 liver stiffness measurements (LSM) were obtained after a fasting time of at least 3 h, with an interquartile (IQRe) range / median < 30%. Median controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) values ≥ 274 db/m were considered indicative of steatosis, median LSM ≥ 8.2 kPa was considered indicative of significant (≥ F2) fibrosis, whereas values ≥ 9.7 kPa were considered indicative of F3–F4 [6].

A patient was considered aware of a liver condition if he answered “yes” to the following question, which was part of the medical conditions questionnaire: “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you had any kind of liver condition?” Furthermore, if the patient answered positively to the previous question, information was gathered on the type of liver disease, which was classified as follows: “fatty liver”, “liver fibrosis”, “liver cirrhosis”, “viral hepatitis”, “autoimmune hepatitis” and “other liver disease”.

Viral hepatitis was also assessed by measuring Hepatitis C RNA and confirmed antibodies and hepatitis B surface antigen. Laboratory methods for measurements of HbA1c, glucose, lipid profile, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), γ-glutamyltranspeptidase (GGT), platelet count and albumin are reported in detail elsewhere [7].

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina), accounting for the complex survey design of NHANES. We used appropriate weighting for each analysis, as suggested by the NCHS. Data are expressed as numbers and weighted proportions for categorical variables and as weighted means ± Standard Error (SE) for continuous variables. Awareness of liver disease across degrees of liver fibrosis was compared using the design-adjusted Rao-Scott chi-square test. A two-tailed value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 825 patients (52.9% men, mean age 60.6 ± 1.05 years, mean body mass index 33.3 ± 0.53 kg/m2) were included in the analysis and their clinical and metabolic features are shown in Table 1. A total of 557 patients had evidence of steatosis (weighted prevalence 73.8%, 95% CI 68.5%–78.5%) and 119 had evidence of advanced (F3–F4) fibrosis (weighted prevalence 15.4%, 95% CI 12.2%-19.0%). AST, ALT and GGT levels increased progressively going from patients with F0–F1 (20.1 IU/L, 22.2 IU/L and 30.6 IU/L) to those with F2 (26.7 IU/L, 34.3 IU/L and 44.9 IU/L) and F3-F4 (30.2 IU/L, 32.7 IU/L and 64 IU/L, p < 0.01 for all).

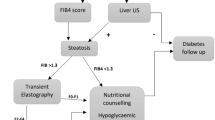

Awareness of any liver condition was 7.5% (95% CI 5.1%–10.8%) in the entire population and not significantly different at 8.1% (95% CI 5.1%–12.7%) in patients with steatosis. Furthermore, it increased going from patients with F0–F1 (4.9%, 95% CI 2.9%–7.8%) to those with F2 (11.8%, 95% CI 5.3%–24.3%) and F3–F4 (17.9%, 95% CI 8.8%–33.3%), as shown in Fig. 1, panel a. The difference was significant between patients in the F3–F4 and in the F0–F1 group (p = 0.004), but not between F0–F1 and F2 or between F2 and F3–F4. No significant differences were found in the reported type of liver disease, with fatty liver being the most common condition in all groups (52.2%–66.5%), followed by viral hepatitis (13.9%–28.5%) and “other” causes, which can be mainly attributed to alcohol (Fig. 1, Panels b and c).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study highlighting the low awareness of having a liver condition in a representative population of US adults with T2D. We show that, although awareness increases with increasing severity of liver disease, it is lower than 20% even in patients with elastographic evidence of advanced fibrosis.

In a previous study performed in the general US population, Singh et al. found that awareness of liver disease was extremely low among individuals with suspected NAFLD (defined as a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 and elevated ALT levels), with an increase from 1.5% to 3.1% from 2001–2004 to 2013–2016 [8]. Importantly, awareness was also low in patients with advanced fibrosis estimated through non-invasive scores. Similarly, in a study from Colorado, among subjects at high metabolic risk attending an endocrinology clinic of a single academic hospital, only 18% were aware of NAFLD as a disease entity [9].

Our estimates expand data from the existing literature by focusing exclusively on patients with T2D and evaluating whether the degree of liver fibrosis assessed through a well-performing and validated non-invasive technique impacts on the level of awareness. It should also be considered that mean diabetes duration in our study was ~ 10 years and that the prevalence of advanced liver fibrosis might be higher in populations with a longer diabetes history. Several explanations can be advanced to explain this lack of awareness.

First, lack of awareness on prevalence, diagnosis and guidelines for NAFLD has been shown among primary care physicians and non-hepatologist hospital specialists. In a study from Queensland, 51% of primary care physicians believed the prevalence of NAFLD to be lower than 10% in the general population and 70.6% said they were unlikely to refer a patient to hepatology unless liver function tests were abnormal [10]. Similarly, 71% of hospital specialists from the same area make no referrals to hepatology for suspected NAFLD [11]. Second, chronic liver disease and NAFLD in particular do not lead to symptoms until decompensated cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma develop, which occurs in a low number of subjects.

Third, as a consequence of a lack of evidence on cost-effectiveness of NAFLD screening and uncertainties on how to perform it, guidance from international societies has been heterogeneous. While guidelines from the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), Diabetes (EASD) and Obesity (EASO) recommend routine screening for NAFLD in patients with T2D, independently from liver enzymes, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases does not endorse it, but encourages case finding if suspicion of NASH is high [12].

Our study has the advantage of a relatively large sample of patients with T2D and a high level of generalizability to the US population. Moreover, it is, to our knowledge, the first study to report awareness across the spectrum of liver fibrosis assessed by transient elastography, which is among the best performing and most validated non-invasive techniques to detect liver fibrosis. Nonetheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, lack of liver biopsy data does not allow to report the prevalence of steatohepatitis and different degrees of fibrosis. Second, data on alcohol consumption are not available, preventing us from quantifying the exact contribution of NAFLD to the measured prevalence of advanced fibrosis. On the other hand, LSM cutoffs to identify F3–F4 fibrosis are similar in different liver conditions. Therefore, irrespective of the specific etiology, we show that few patients with advanced liver fibrosis are aware of their condition.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in a nationally representative sample of US adults with T2DM, prevalence of advanced liver fibrosis is high. Nonetheless, less than 20% of those with advanced fibrosis are aware of having any kind of liver condition.

Data availability and material

All data used in this study are publicly available online at the NHANES website.

Abbreviations

- T2D:

-

Type 2 diabetes

- NAFLD:

-

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH:

-

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- TE:

-

Transient elastography

- LSM:

-

Liver stiffness measurement

- CAP:

-

Controlled attenuation parameter

- NHANES:

-

National health and nutrition examination survey

References

Zoppini G, Fedeli U, Gennaro N et al (2014) Mortality from chronic liver diseases in diabetes. Am J Gastroenterol 109(7):1020–1025. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2014.132

Bjorkstrom K, Franzen S, Eliasson B et al (2019) Risk factors for severe liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2019.04.038

Ciardullo S, Muraca E, Perra S et al (2020) Screening for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in type 2 diabetes using non-invasive scores and association with diabetic complications. BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care 8(1):e000904. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2019-000904

Bril F, Cusi K (2017) Management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: a call to action. Diabetes Care 40(3):419–430. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc16-1787

Ciardullo S, Sala I, Perseghin G (2020) Screening strategies for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in type 2 diabetes: insights from NHANES 2005–2016. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108358

Eddowes PJ, Sasso M, Allison M et al (2019) Accuracy of FibroScan controlled attenuation parameter and liver stiffness measurement in assessing steatosis and fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 156(6):1717–1730

Centers for disease control and prevention. 2017: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). U.S. Department of health and human services. Available from https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/2017-2018/manuals/2017_MEC_Laboratory_Procedures_Manual.pdf accessed 31 March 2020.

Singh A, Dhaliwal AS, Singh S et al (2020) Awareness of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is increasing but remains very low in a representative US Cohort. Dig Dis Sci 65(4):978–986. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-019-05700-9

Wieland AC, Mettler P, McDermott MT et al (2015) Low awareness of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among patients at high metabolic risk. J Clin Gastroenterol 49(1):e6–e10. https://doi.org/10.1097/mcg.0000000000000075

Patel PJ, Banh X, Horsfall LU et al (2018) Underappreciation of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by primary care clinicians: limited awareness of surrogate markers of fibrosis. Intern Med J 48(2):144–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.13667

Bergqvist CJ, Skoien R, Horsfall L et al (2013) Awareness and opinions of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by hospital specialists. Intern Med J 43(3):247–253

Leoni S, Tovoli F, Napoli L et al (2018) Current guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review with comparative analysis. World J Gastroenterol 24(30):3361

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Milano - Bicocca. The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SC and GP designed the study, wrote, reviewed and edited the manuscript. SC participated in data analysis. TM researched and analyzed data and participated in writing and editing the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be published. GP is the guarantor of this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest related to this article was reported.

Code availability

Code is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all adult participants.

Ethics approval

The original survey was approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Research Ethics Review Board. The present analysis was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board at our institution, as the dataset used in the analysis was completely de-identified.

Additional information

Managed By Massimo Porta.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ciardullo, S., Monti, T. & Perseghin, G. Lack of awareness of liver organ damage in patients with type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol 58, 651–655 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-021-01677-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-021-01677-y