Abstract

Purpose

To utilize a global survey to elucidate spine surgeons’ perspectives towards research and resident education within telemedicine.

Methods

A cross-sectional, anonymous email survey was circulated to the members of AO Spine, an international organization consisting of spine surgeons from around the world. Questions were selected and revised using a Delphi approach. A major portion of the final survey queried participants on experiences with telemedicine in training, the utility of telemedicine for research, and the efficacy of telemedicine as a teaching tool. Responses were compared by region.

Results

A total of 485 surgeons completed the survey between May 15, 2020 and May 31, 2020. Though most work regularly with trainees (83.3%) and 81.8% agreed that telemedicine should be incorporated into clinical education, 61.7% of respondents stated that trainees are not present during telemedicine visits. With regards to the types of clinical education that telemedicine could provide, only 33.9% of respondents agreed that interpretation of physical exam maneuvers can be taught (mean score = − 0.28, SD = ± 1.13). The most frequent research tasks performed over telehealth were follow-up of imaging (28.7%) and study group meetings (26.6%). Of all survey responses provided by members, there were no regional differences (p > 0.05 for all comparisons).

Conclusions

Our study of spine surgeons worldwide noted high agreement among specialists for the implantation of telemedicine in trainee curricula, underscoring the global acceptance of this medium for patient management going forward. A greater emphasis towards trainee participation as well as establishing best practices in telemedicine are essential to equip future spine specialists with the necessary skills for navigating this emerging platform.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Telemedicine, the remote delivery of clinical care through videoconferencing or audio platforms, has experienced explosive growth in light of the COVID-19 pandemic [1, 2]. Social distancing practices have drastically altered the practice of orthopaedic care, requiring the cessation of nonurgent surgeries and a need for alternative means of care delivery to high-risk populations. Providers and patients alike have rapidly turned to telemedicine as a surrogate means of establishing care [3, 4]. While pre-pandemic predictions valued the 2025 telemedicine market beyond $64 billion, the present climate suggests even further growth as pandemic precautions and social guidelines persist [5].

Early evidence has demonstrated overall provider satisfaction with telemedicine across all specialties [6,7,8,9]. Among arthroplasty and sports medicine surgeons, telemedicine has demonstrated initial utility in providing follow-up care and at-home rehabilitation to patients [10,11,12,13]. However, there remains a lack of best practices for implementing this platform into both orthopaedic surgery trainee curricula and research. As institutions convert to a “new normal” of practice management, it is imperative to consider how budding spine surgeons are best trained in a learning environment that is rapidly adapting to external forces in order to continue to deliver high-quality care.

To our knowledge, no prior studies have evaluated if or how telemedicine should be incorporated into training spine surgery residents or fellows. Given the recent ubiquity of telemedicine use and its early benefit in supporting resident training, those formulating Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) compliant curricula must consider current implementation of and attitudes towards telemedicine [14, 15]. The purpose of this study was to survey spine surgeons’ perspectives towards research and resident education within telemedicine.

Methods

Survey design

An anonymous, cross-sectional global survey, entitled “Telemedicine & the Spine Surgeon: Perspectives and Practices Worldwide”, was conducted to assess spine surgeons’ attitudes towards telemedicine (“Appendix 1”). The survey was formulated through a modified Delphi approach, in which all questions underwent four consecutive rounds of review by the multi-disciplinary study authors [16]. To maintain anonymity, no identifying information was collected from survey respondents. The final version consisted of 42 questions, covering seven critical categories as determined by the study authors.

The seventh critical category of our survey consisted of questions pertaining to telemedicine in training and research. In addition to its impact on patient care, the COVID-19 pandemic has upended how the next generation of surgeons is trained. Furthermore, it has forced providers to quickly adopt a new form of patient evaluation into their practice, raising questions on whether trainees should be formally educated on the use of telemedicine. Survey participants were asked about the presence of trainees in telemedicine visits, their stances on formal telemedicine education, and whether telemedicine may be used to teach clinical skills (i.e. physical exam, interpretation of imaging, etc.). Similarly, participants’ use of telemedicine for research activities was explored (“Appendix 1”).

Respondent sample

The above survey was distributed via electronic mail to members of AO Spine from all 5 AO regions who elected to receive relevant surveys [1]. AO Spine is currently the largest international organization dedicated to practice and study of spine surgery, comprised of over 6000 actively practicing spine surgeons (www.aospine.org). The survey period began on May 15, 2020. An email reminder was sent on May 24, 2020, prior to the survey closing on May 31, 2020. Additionally, each AO Spine Regional Director and Regional Research Officer was approached to personally connect and reach out to (the same) members in their region (i.e. Country Council Chairs, Fellowship Officers, etc.) regarding participation.

Statistical analyses

All questions presented were optional, thus both incomplete and completed surveys were counted in the final analysis. Incomplete data points were excluded per analysis. Given the extent of content accumulated from the 42-question survey, statistical analyses were divided into four major themes: global perspectives, challenges and benefits, telemedicine evaluation, and training and research. The present analysis is focused specifically on questions pertaining to the utility of telemedicine in training and research. Survey respondents were grouped into five geographical regions, namely Africa, Asia-Pacific, Europe, North America, and South America. Participants were stratified by geographical region, and responses were subsequently compared. Categorical variables were analyzed using Pearson’s chi-square test, and continuous variables were assessed using Mann–Whitney U tests or ANOVA as appropriate. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Version 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Demographics

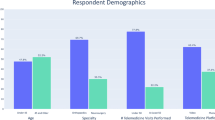

A total of 485 surgeons completed the survey between May 15, 2020 and May 31, 2020. The majority of the sample included both orthopaedic spine surgeons (68.5%, n = 332) and neurosurgeons (29.7%, n = 144). The majority of respondents belonged to either an Academic/University hospital department (34%, n = 164) or a combined Academic/Private practice (26.6%, n = 128). 85.4% of surgeons (n = 408) stated that they practice in an urban setting, while the remainder work in a suburban (13.2%, n = 63) or rural community (1.5%, n = 7) (Table 1). While responses to survey questions regarding the use of telemedicine in education and research were optional, there were over 200 responses provided to each of these questions (Tables 2, 3 and 4).

Telemedicine and training

With regards to provider presence, 21.6% of survey respondents (n = 48) noted that trainees are present during their telemedicine visits, while the majority of respondents stated that no trainees are present (61.7% of respondents, n = 137). 16.7% of respondents stated that they do not normally work with trainees (n = 37). Similarly, 82.8% of surgeons (n = 183 respondents) noted that other providers, including other spine surgeons, approach surgeons, or primary care providers, are not present during telemedicine visits. When asked if telemedicine should be incorporated into resident/fellow training in the clinical setting, 81.8% stated “Yes” (n = 180) (Table 2).

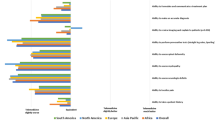

A total of 218 respondents completed questions related to telemedicine and training. Mean Likert scale values demonstrated that more than half of respondents agreed with the statements that telemedicine should be part of the medical school curriculum (mean score = 0.77, SD = ± 0.88), and that telemedicine should be incorporated as part of residency/fellowship training (mean score = 0.77, SD = ± 0.89). Additionally, most respondents agreed that both directed history taking (mean score = 0.84, SD = ± 0.78) and interpretation of imaging studies (mean score = 0.97, SD = ± 0.83) can be taught via telemedicine. Only 33.9% of respondents agreed that interpretation of physical exam maneuvers can be taught via telemedicine (mean score = − 0.28, SD = ± 1.13), and most respondents disagreed with the statements “I prefer teaching via telemedicine to in-person” (mean score = −0.41, SD = ± 1.03) and “teaching over telemedicine is as effective as in-person teaching” (mean score = − 0.36, SD = ± 1.03) (Table 3).

Telemedicine and research

AO Spine members were also surveyed with regards to the use of telemedicine and research. 28.7% of surgeons stated that they have utilized telemedicine for follow-up of imaging (n = 139). Other more frequently cited uses of telemedicine were study group meetings (26.6%, n = 129 and for follow-up of Health-related Quality of Life (HRQL) or other survey questionnaires (22.1%, n = 107) (Table 4).

Comparison by region and age

Of the survey responses provided by members, there was no statistically significant difference when stratified by region and by age (> 55 years old) (Pearson Chi-squared > 0.05 for all associations) (“Appendices 2, 3, 4”).

Discussion

The present study focused on AO Spine members’ contemporary perspectives towards telemedicine with regards to training and research. Most practitioners (61.7%, n = 137) reported that they currently do not have trainees present during telemedicine visits. Nevertheless, 81.8% of respondents stated that they believe telemedicine should be incorporated into resident and/or fellowship training in a clinical setting (Table 2). Provider attitudes towards telemedicine and training were somewhat mixed; mean Likert scores were in highest agreement for the utility of telemedicine for teaching history-taking, evaluating imaging, and the incorporation of telemedicine into training curricula. The lowest mean Likert score was reported for the interpretation of physical findings (mean score = − 0.28, SD = ± 1.13). With regards to research, surveyed members most commonly utilize telemedicine for follow-up of radiographs/imaging or study group meetings (Table 4). Our findings suggested that respondents’ perspective did not differ by geographic region (Pearson Chi-squared > 0.05 for all scores).

As telemedicine becomes increasingly utilized in musculoskeletal care and appears to be a prominent platform moving forward, it is critical that budding spine surgeons undergo sufficient training with virtual healthcare platforms in order to deliver high-quality care. Our results suggest a gap between the current exposure trainees have to what spine surgeons feel trainees should have in practice. Traditionally, junior and attending physicians both perform independent evaluations of a patient, followed by a debriefing. Here, trainees may receive valuable feedback with regards to their interviewing, examination and diagnostic skills, and bedside manner [17]. This process is also crucial for training in telemedicine. Afshari et al. [18] trialled a didactic and clinical-based virtual healthcare curriculum for neurology residents, formulated to assess trainees attitudes toward and challenges faced when utilizing telemedicine. When evaluating subjects’ performance, the authors found that residents adapted quickly to videoconferencing systems but felt less comfortable in building a strong physician–patient relationship in comparison with an in-person visit. Similar literature has suggested that developing a strong “webside manner” requires sufficient time and practice [19, 20]. Moving forward, we feel that senior spine surgeons should be encouraged to involve their peers and juniors when performing telemedicine visits, allowing for more frequent and effective exposure.

Fortunately, implementation of formal telemedicine training into trainee curricula has already been initiated. In 2016, the American Medical Association implemented a policy “encouraging the accrediting bodies for both undergraduate and graduate medical education to include core competencies for telemedicine in their programs.”[21] Our survey results support these changes; the majority of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that telemedicine should both be part of the medical school curriculum and incorporated as part of residency/fellowship training (Table 3). Jagolino et al. [22] incorporated a formal telemedicine rotation into their neurology fellowship program. From their early experiences, the authors reported that fellows’ attitudes towards telemedicine were largely positive, and that 81% of subjects agreed that telemedicine should be required in a one-year ACGME-accredited vascular fellowship. Similar pilot curricula have been developed within medical schools, internal medicine, family medicine, and dermatology residencies, with modest early success [14, 23,24,25].

Despite these early advances, implementation of formal telemedicine training is challenged by a diverse array of platforms and technologies and their associated technical difficulties and the lack of standardized physical examination practices [14, 26, 27]. Our results indicate that, while spine surgeons may be as comfortable imparting history-taking skills and evaluation of imaging via telemedicine, the inherent remote nature of the visit creates a unique challenge in teaching orthopaedic/neurologic physical examination maneuvers (Table 3). While surrogate physical exam maneuvers have been suggested [27, 28], we recognize that this aspect of training may be best learned in a traditional manner. Moving forward, establishing a uniform spine telemedicine visit structure, with standardization of all clinical components of the visit, will likely enhance the trainee experience.

Few prior studies have evaluated the utility of telemedicine when conducting musculoskeletal research. While telemedicine has provided a surrogate infrastructure to traditional, in-person clinical care during the COVID-19 crisis, our survey suggests that musculoskeletal research has not yet benefitted from the gross introduction of videoconferencing as seen in the clinical setting. 28.7% (n = 139) and 26.6% (n = 129) of respondents noted that they have utilized telemedicine for follow-up of imaging and/or study group meetings. Similarly, Upadhaya et al. [29] noted that patient enrolment in active oncology clinical trials have been severely negatively affected, including over 200 interventional trials between March and April of 2020. Cancer researchers have noted that temporary regulatory waivers by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) may make telemedicine a useful tool in maintaining and furthering medical research during this pandemic [29,30,31]. The cost and convenience of telemedicine, coupled with permissive use of previously non-HIPAA complaint videoconferencing platforms (eg. Zoom, Skype for Business, GoogleChat) [32], may provide spine surgeons with a key tool in conducting research moving forward.

Our investigation was not without limitations. First, responses to survey questions were optional; therefore, our results fail to capture the current practices of all respondents (n = 485). In addition, certain regions were likely underrepresented (e.g. North America). Second, while the majority of respondents were orthopaedic surgeons, neurosurgeons, traumatologists, pediatric surgeons, and other practicing physicians also contributed. The diversity of pathologies and patients that these practitioners treat, coupled with the potential for varying levels of experience, likely create similarly unique telemedicine practices. However, we do not suspect that this would significantly influence their perspectives towards research and education within telemedicine. Third, we note that our lack of statistical power limits our ability for stratification and comparison by region. Fourth, we did not compare attitudes towards telehealth across different practice types, hospital communities or population size served. Lastly, as telemedicine was adopted extremely rapidly, negative attitudes towards telemedicine may be rooted in inexperience. As practitioners and trainees become more comfortable with remote healthcare, the potential benefits of telemedicine as a clinical and training tool may become more evident.

Conclusions

Our study of spine surgeons worldwide noted high agreement among specialists for the implantation of telemedicine in trainee curricula. Over 80% of members responding agreed that telemedicine deserves a formal role in the clinical setting in residencies and fellowship programs. However, surgeons disagreed that telemedicine is as effective as in-person training or is a preferred method of teaching. Survey respondent perspectives towards the utility of training and research within telemedicine did not differ based on geographical region, which underscores the global acceptance and universal appeal of this medium for patient management. Given the rapid surge in telemedicine use, we believe that assessing contemporary perspectives with regards to telemedicine and research and training is key to improving virtual healthcare quality. While significant progress has been made in addressing the technical challenges and unfamiliarity associated with telemedicine, further attention must be paid towards establishing best practices in telemedicine training and research, in order to fully equip future spine specialists with the necessary skills for navigating this novel platform.

References

Louie PK, Harada GK, McCarthy MH et al (2020) The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on spine surgeons worldwide. Glob Spine J 10:534–552. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568220925783

Swiatek P, Weiner J, Johnson D et al (2021) COVID-19 and the rise of virtual medicine in spine surgery: a worldwide study

Miliard M (2020) Telehealth set for “tsunami of growth,” says Frost & Sullivan. In: Healthc. IT News

Portnoy J, Waller M, Elliott T (2020) Telemedicine in the era of COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 8:1489–1491

U.S. Telemedicine Market Statistics 2019–2025 (2020) Share forecasts, trends & growth drivers. MarketWatch

Kwok J, Olayiwola JN, Knox M et al (2018) Electronic consultation system demonstrates educational benefit for primary care providers. J Telemed Telecare. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X17711822

Lee MS, Ray KN, Mehrotra A et al (2018) Primary care practitioners’ perceptions of electronic consult systems: a qualitative analysis. JAMA Int Med 178:782

Good DW, Lui DF, Leonard M et al (2012) Skype: a tool for functional assessment in orthopaedic research. J. Telemed. Telecare 18:94–98

Lamminen H, Nevalainen J, Alho A et al (1996) Experimental telemedicine in orthopaedics. J Telemed Telecare. https://doi.org/10.1258/1357633961930013

Buvik A, Bugge E, Knutsen G et al (2016) Quality of care for remote orthopaedic consultations using telemedicine: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res 16:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1717-7

Kane LT, Thakar O, Jamgochian G et al (2020) The role of telehealth as a platform for postoperative visits following rotator cuff repair: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elb Surg 29:775–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2019.12.004

Nicholson KJ, Millhouse PW, Pflug E et al (2018) Cervical sagittal range of motion as a predictor of symptom severity in cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000002478

Sharareh B, Schwarzkopf R (2014) Effectiveness of telemedical applications in postoperative follow-up after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2013.09.019

Lee MS, Nambudiri V (2019) Integrating telemedicine into training: adding value to graduate medical education through electronic consultations. J Grad Med Educ. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-18-00754.1

ACGME (2020) ACGME Common Program Requirements (Residency). Accredit Counc Med Educ

Okoli C, Pawlowski SD (2004) The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Inf Manag 42:15–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2003.11.002

Clark R, Evans EB, Ivey FM et al (1989) Characteristics of successful and unsuccessful applicants to orthopedic residency training programs. Clin Orthop Relat Res. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-198904000-00035

Afshari M, Witek NP, Galifianakis NB (2019) Education Research: an experiential outpatient teleneurology curriculum for residents. Neurology. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000007848

McConnochie KM (2019) Webside manner: a key to high-quality primary care telemedicine for all. Telemed. e-Health 25:1007–1011

Chua IS, Jackson V, Kamdar M (2020) Webside manner during the COVID-19 pandemic: maintaining human connection during virtual visits. J Palliat Med. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2020.0298

AMA (2016) AMA encourages telemedicine training for medical students, residents

Jagolino AL, Jia J, Gildersleeve K et al (2016) A call for formal telemedicine training during stroke fellowship. Neurology. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000002568

Wanat KA, Newman S, Finney KM et al (2016) Teledermatology education: current use of teledermatology in US residency programs. J. Grad. Med. Educ 8:286–287

Williams CM, Kedar I, Smith L et al (2005) Teledermatology education for internal medicine residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2005.01.111

Kamdar N (2019) It’s time for ACGME to require telemedicine training for residents. Op-Med

Wongworawat MD, Capistrant G, Stephenson JM (2017) The opportunity awaits to lead orthopaedic telehealth innovation. J Bone Jt Surg Am. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.16.01095

Tanaka MJ, Oh LS, Martin SD, Berkson EM (2020) Telemedicine in the era of COVID-19: the virtual orthopaedic examination. J Bone Jt Surg Am. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.20.00609

Iyer S, Shafi K, Lovecchio F et al (2020) The spine physical examination using telemedicine: strategies and best practices. Glob spine J. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568220944129

Upadhaya S, Yu JX, Oliva C et al (2020) Impact of COVID-19 on oncology clinical trials. Nat Rev Drug Discov 19:376–377

Waterhouse DM, Harvey RD, Hurley P et al (2020) Early impact of COVID-19 on the conduct of oncology clinical trials and long-term opportunities for transformation: findings from an American society of clinical oncology survey. JCO Oncol Pract. https://doi.org/10.1200/op.20.00275

Kenneth Y, Allison Fulton MG (2020) Going virtual: clinical trials, telemedicine, electronic medical records, and all thatle. SheppardMullin

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020) Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth remote communications during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. HHS gov

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their sincere gratitude to Kaija Kurki-Suonio and Fernando Kijel from AO Spine (Davos, Switzerland) for their assistance with circulating the survey to AO Spine members

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial or competing interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shafi, K., Lovecchio, F., Riew, G.J. et al. Telemedicine in research and training: spine surgeon perspectives and practices worldwide. Eur Spine J 30, 2143–2149 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-020-06716-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-020-06716-w