Abstract

Purpose

We prospectively investigated contamination of high-contact surfaces in the operating room (OR) using adenosine triphosphate (ATP) monitoring. We tested whether contamination would increase from morning (AM) to afternoon (PM), despite cleaning between cases. Second, we compared the degree of OR contamination to non-OR control sites.

Methods

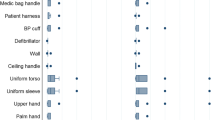

ORs with high case volumes were selected for the study. Ten sites in each OR were swabbed using the AccuPoint® HC ATP Sanitation Monitoring device, which provided a numerical measure of contamination (relative light units, RLUs). According to the manufacturer, surfaces are considered clean at ≤ 400 RLUs. AM measurements were taken before the start of surgical cases and PM measurements were taken after cases were completed.

Results

Eighty morning and 70 afternoon samples were obtained from 8 ORs. Apart from the OR floor, laryngoscope handles had the highest level of morning contamination (1204 RLUs, interquartile range 345, 2603), with 75% of AM samples and 100% of PM samples exceeding 400 RLUs. This contamination was comparable to hospital toilet seats (87% of samples exceeding 400 RLUs). No sites showed statistically significant increases in contamination from AM to PM.

Conclusion

Apart from the OR floors, laryngoscope handles emerged as a key OR site where improved cleaning practices may reduce cross-contamination risk. While some sites showed increased contamination over the course of the day, none of these met statistical significance thereby offering tentative evidence that current cleaning practices during case turnover are effective for most sites.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Nante N, Ceriale E, Messina G, Lenzi D, Manzi P. Effectiveness of ATP bioluminescence to assess hospital cleaning: a review. J Prevent Med Hyg. 2017;58:E177–83.

Amodio E, Dino C. Use of ATP bioluminescence for assessing the cleanliness of hospital surfaces: a review of the published literature (1990–2012). J Infect Public Health. 2014;7:92–8.

Shakir IA, Patel NH, Chamberland RR, Kaar SG. Investigation of cell phones as a potential source of bacterial contamination. J Bone Joint Surg. 2015;97:225–31.

Alfa MJ, Fatima I, Olson N. Validation of adenosine triphosphate to audit manual cleaning of flexible endoscope channels. Am J Inf Control. 2013;41:245–8.

Jones BL, Gorman LJ, Simpson J, Curran ET, McNamee S, Lucas C, Michie J, Platt DJ, Thakker B. An outbreak of Serratia marcescens in two neonatal intensive care units. J Hosp Infect. 2000;46:314–19.

Neal TJ, Hughes CR, Rothburn MM, Shawn NJ. The neonatal laryngoscopes as a potential source of cross-infection. J Hosp Infect. 1995;30:315–17.

Williams D, Dingley J, Jones C, Berry N. Contamination of laryngoscope handles. J Hosp Infect. 2010;74:123–28.

Muscarella LF. Reassessment of the risk of health care-acquired infection during rigid laryngoscopy. J Hosp Infect. 2008;68:101–7.

Rutala WA, Weber DJ, the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HIPAC). Guidelines for disinfection and sterilization in healthcare facilities: centers for disease control; 2008. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/pdf/guidelines/disinfection-guidelines.pdf. Accessed 23 Feb 2018.

Association of Perioperative Registered Nurses–Recommended Practices Committee. Recommended practices for cleaning, handling and processing anesthesia equipment. AORN J. 2005;81:856–70.

Infection Control Guide for Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists; 2012. http://www.aana.com/practicemanual. Accessed 17 Feb 2018.

American Society of Anesthesiologists Committee on Occupational Health Task Force on Infection Control. Recommendations for Infection Control for the Practice of Anesthesiology. 3rd ed. 2011. http://www.asahq.org/resources/resources-from-asa-committees#ic. Accessed 17 Feb 2018.

Sherman JD, Hopf HW. Balancing infection control and environmental protection as a matter of patient safety: the case of laryngoscope handles. Anesth Analg. 2018;127:576–9.

Amour J, Le Manach Y, Borel M, Lenfant F, Nicolas-Robin A, Carillion A, Ripart J, Riou B, Langeron O. Comparison of single-use and reusable metal laryngoscope blades for orotracheal intubation during rapid sequence induction of anesthesia: a multicenter cluster randomized study. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:325–32.

Sherman JD, Raibley LA, Eckelman MJ. Life cycle assessment and costing methods for device procurement: comparing reusable and single-use disposable laryngoscopes. Anesth Analg. 2018;127:434–43.

McGain F, Story D, Lim T, McAlister S. Financial and environmental costs of reusable and single-use anesthetic equipment. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118:862–9.

Birnbach DJ, Rosen LF, Fitzpatrick M, Carling P, Arheart KL, Munoz-Price SL. Double gloves: a randomized trial to evaluate a simple strategy to reduce contamination in the operating room. Anesth Analg. 2015;120:848–52.

Birnbach DJ, Rosen LF, Fitzpatrick M, Carling P, Arheart KL, Munoz-Price SL. A new approach to pathogen containment in the operating room: sheathing the laryngoscope after intubation. Anesth Analg. 2015;121:1209–14.

Alfa MJ, Fatima I, Olson N. The adenosine triphosphate test is a rapid and reliable audit tool to assess manual cleaning adequacy of flexible endoscope channels. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41:249–53.

Richard RD, Bowen TR. What orthopaedic operating room surfaces are contaminated with bioburden? A study using the ATP bioluminescence assay. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475:1819–24.

Gibbs SG, Sayles H, Chaika O, Hewlett A, Colbert EM, Smith EW. Evaluation of the relationship between ATP bioluminescence assay and the presence of organisms associated with healthcare-associated infections. Healthc Infect. 2014;19:101–7.

Acknowledgements

No funding or support was provided for the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Ramirez, A., Mohan, S., Miller, R. et al. Surface contamination in the operating room: use of adenosine triphosphate monitoring. J Anesth 33, 85–89 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00540-018-2590-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00540-018-2590-9