Abstract

Background

A reliable system for grading operative difficulty of laparoscopic cholecystectomy would standardise description of findings and reporting of outcomes. The aim of this study was to validate a difficulty grading system (Nassar scale), testing its applicability and consistency in two large prospective datasets.

Methods

Patient and disease-related variables and 30-day outcomes were identified in two prospective cholecystectomy databases: the multi-centre prospective cohort of 8820 patients from the recent CholeS Study and the single-surgeon series containing 4089 patients. Operative data and patient outcomes were correlated with Nassar operative difficultly scale, using Kendall’s tau for dichotomous variables, or Jonckheere–Terpstra tests for continuous variables. A ROC curve analysis was performed, to quantify the predictive accuracy of the scale for each outcome, with continuous outcomes dichotomised, prior to analysis.

Results

A higher operative difficulty grade was consistently associated with worse outcomes for the patients in both the reference and CholeS cohorts. The median length of stay increased from 0 to 4 days, and the 30-day complication rate from 7.6 to 24.4% as the difficulty grade increased from 1 to 4/5 (both p < 0.001). In the CholeS cohort, a higher difficulty grade was found to be most strongly associated with conversion to open and 30-day mortality (AUROC = 0.903, 0.822, respectively). On multivariable analysis, the Nassar operative difficultly scale was found to be a significant independent predictor of operative duration, conversion to open surgery, 30-day complications and 30-day reintervention (all p < 0.001).

Conclusion

We have shown that an operative difficulty scale can standardise the description of operative findings by multiple grades of surgeons to facilitate audit, training assessment and research. It provides a tool for reporting operative findings, disease severity and technical difficulty and can be utilised in future research to reliably compare outcomes according to case mix and intra-operative difficulty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a common operation which may vary in operative difficulty. For example, it can be a routine operation comfortably performed by a training grade surgeon (with appropriate supervision) but, at its most difficult, can tax even the most experienced specialist surgeon. It is therefore surprising that very few intra-operative difficulty scores have been published and none are widely used in clinical practice [1,2,3]. Moreover, none have been utilised in a large multi-centre study. The majority of previous scores use a combination of pre-operative and operative data and were produced in studies that were limited by retrospective data, small sample sizes and lack of external validation [1, 4,5,6]. Being able to stratify intra-operative difficulty with a simple scale of operative difficulty would have the advantages of assisting in intra-operative strategy and planning, allowing comparison across different research studies, facilitating risk adjustment for surgical outcomes and providing an aid in training surgeons and monitoring of training progression.

The Nassar operative difficulty scale is a simple 4-point scale published in 1995 and has been used in a prospective single-surgeon series which included data from 4089 patients between February 1992 and July 2014. The aim of this study was to report the utilisation of this operative grading system for laparoscopic cholecystectomy using data collected from the recent multi-centre CholeS study [7,8,9,10,11] and assess the grading system’s clinical utility in its association with outcome data.

Patients and methods

For this study two large, prospective datasets containing patients treated with cholecystectomy were used.

Reference dataset

This database started in 1992 and includes all cases managed by a single-consultant Upper GI Surgeon (AHM Nassar) in four hospitals over 22 years. The database was registered as a clinical audit in each hospital and did not require specific IRB approval. A difficulty grade was prospectively recorded for each cholecystectomy. Strict follow-up was conducted and recorded, including any complications, readmissions or 30-day reinterventions as well as outpatient review at 2–3 months. The follow-up protocol for the later part of the series (1995–2014) included 3763 cholecystectomies at two hospitals with one follow-up appointment for all laparoscopic cholecystectomies and further annual reviews of all bile duct explorations (819 cases). Follow-up included a review of the complications, readmissions and reinterventions, with emphasis on retained or recurrent stones following bile duct explorations. This is a referral firm receiving, by protocol, the majority of emergency biliary admissions and almost all patients with suspected bile duct stones admitted to the hospital. The practice includes a high rate of single-admission operations with minimal delayed operations. Higher than average rates of intra-operative cholangiography and CBD explorations were carried out, compared to normal surgical practice. Previous publications arising from this dataset and the methodology used for data collection have been published [12,13,14,15,16].

CholeS dataset

The CholeS study was a multi-centre, prospective population-based cohort study of variation and outcomes of cholecystectomy [8, 9]. The protocol did not require research registration as anonymous, and observational data were collected. This was confirmed by the online NRES decision tool (http://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/research/) and further supported by written confirmation and advice from the Research and Development Director at University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, UK. The study was registered as a ‘clinical audit’ or ‘service evaluation’ at each participating hospital under the supervision of a named senior investigator (consultant surgeon).

Data were collected from 8820 patients who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy in 166 hospitals across the UK, during a 2-month period from March to April 2014, and have been found to be 99.2% accurate by independent data validation. Pre-operative variables included patient demographics, indications for surgery, ASA grade, admission type, ultrasound findings and pre-operative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The CholeS study protocol has been published previously [11]. The definitions of operative and outcomes parameters were similar in both studies. The duration of surgery was calculated from time (minutes) of skin incision to end of skin closure. 30-day follow-up was obtained for all patients and included rates of morbidity and mortality. All cause 30-day morbidity included bile leak, bile duct injury, wound infection, intra-abdominal collection, pancreatitis, bile duct stones, as well as non-surgical complications such as cardiac, respiratory, urinary and other complications. Bile duct injury was defined as any injury to the main biliary tree and was classified using the Stewart–Way classification [17]. Bile leak was defined using a standardised definition from the International Study Group of Liver Surgery [18].

Nassar difficultly grading scale

In both datasets, the operative data were gathered prospectively, and surgeons were asked to grade the difficulty of the procedure using the Nassar scale (grades 1–4) [3]. This scale was published in 1995 and graded operative findings from the gallbladder, cystic pedicle and associated adhesions. The scale is as follows:

Grade 1:

Gallbladder—floppy, non-adherent

Cystic pedicle—thin and clear

Adhesions—Simple up to the neck/Hartmann’s pouch

Grade 2:

Gallbladder—Mucocele, Packed with stones

Cystic pedicle—Fat laden

Adhesions—Simple up to the body

Grade 3:

Gallbladder—Deep fossa, Acute cholecystitis, Contracted, Fibrosis, Hartmans adherent to CBD, Impaction

Cystic pedicle—Abnormal anatomy or cystic duct—short, dilated or obscured

Adhesions—Dense up to fundus; Involving hepatic flexure or duodenum

Grade 4:

Gallbladder—Completely obscured, Empyema, Gangrene, Mass

Cystic pedicle—Impossible to clarify

Adhesions—Dense, fibrosis, wrapping the gallbladder, Duodenum or hepatic flexure difficult to separate

The grading system is designed to be used as an overall summary of the operative conditions found, and the worst factor found in the individual aspect of either the ‘Gallbladder’, ‘Cystic Pedicle’ or ‘Adhesions’ should be used to define the final overall grade.

Figure 1 illustrates laparoscopic images of each of the Nassar operative difficulties.

Although the difficultly scale was modified in 1996 in the reference cohort to include a Grade 5 (which was defined as the presence of either Mirizzi type 2 or higher, cholecysto-cutaneous, cholecysto-duodenal or cholecysto-colic fistula), these were combined with Grade 4 for the analysis, in order to be comparable to the scale used in the CholeS dataset and the original publication. Less than 1% of patients in the reference database had a Grade 5 operative difficulty.

Statistical methods

Initially, a range of factors and patient outcomes were compared between the two cohorts. Continuous variables were assessed for normality, prior to the analysis. Normally distributed variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD), with p values from independent samples t tests. Medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) and Mann–Whitney tests were used where the normality assumption was not met. Nominal variables were compared using Fisher’s exact tests, with Kendall’s tau used for ordinal variables.

Patient outcomes were then correlated with Nassar operative difficultly scale, using Kendall’s tau for dichotomous variables, or Jonckheere–Terpstra tests for continuous variables. A ROC curve analysis was then performed, to quantify the predictive accuracy of the Nassar operative difficultly scale for each of the outcomes, with continuous outcomes dichotomised, prior to analysis.

The four key outcomes were then selected (conversion to open, the duration of surgery and both complications and reinterventions within 30 days), and analysed in further detail. Initially, these outcomes were compared across a range of factors, using Fisher’s exact test or Mann–Whitney/Kruskal–Wallis tests, as applicable. Multivariable analyses were then performed, to identify combinations of factors that were independently predictive of the outcomes. Binary logistic regression models were used, with variable selection by a backwards stepwise approach.

All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 22 (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY). Patients with missing data were excluded on a test by test basis and p < 0.05 was deemed to be indicative of statistical significance throughout.

Results

Demographics

A total of 4089 cases were included in the reference cohort and 8755 operations in the CholeS cohort. Data were complete in at least 95% of cases in each of the factors considered for both of the cohorts, with the exception of ASA (85%) and length of stay (51%) in the reference cohort. Patient demographics, operative factors and outcomes are compared between the cohorts in Table 1. This identified a range of differences between the two cohorts. For example, higher percentage of emergency admissions was found in the reference dataset due to the nature of the referral protocol of the acute biliary service. However, there were higher rates of cholecystitis and thick-walled gallbladders in the CholeS dataset. MRCP and ERCP were used less frequently in the reference dataset, due to a preference to perform intra-operative cholangiography. There was also a higher rate of CBD exploration, drain use and length of hospital stay in the reference cohort.

Associations with Nassar operative difficulty scale

Associations between the Nassar operative difficulty scale, operative factors and patient outcomes were then examined (Table 2). Due to the previously identified differences between the reference and CholeS cohorts, the two datasets were analysed separately.

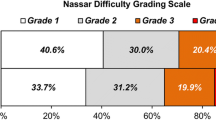

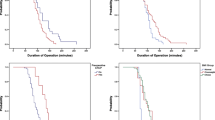

Increasing Nassar operative difficulty scale was consistently associated with significantly worse outcomes for the patients in the CholeS cohort. For example, the median length of stay increased from 0 to 4 days, and the 30-day complication rate from 7.6 to 24.4% as the Nassar scale increased from 1 to 4/5 (both p < 0.001). Similar outcomes were observed in the reference cohort, although not all of the associations reached significance in both cohorts. However, the outcomes where no significant association with the Nassar scale was detected were rare events where statistical power would have been too low to identify a trend. For example, CBD injury, which was not found to be significantly associated with the Nassar scale (p = 0.325) in the reference cohort, only occurred in n = 2 patients. Selected outcomes are also reported graphically in Fig. 2.

The relationships between Nassar scale and both operative factors and patient outcomes were also considered in a ROC curve analysis (Table 3). Surgical duration and length of stay were dichotomised, using cut-off values of > 90 min and > 5 days, respectively. In the CholeS cohort, the Nassar scale was found to be most strongly associated with conversion to open and 30-day mortality (AUROC = 0.903, 0.822, respectively).

Other predictors of patient outcome

Four clinically relevant outcomes, namely conversion to open, the duration of surgery and both complications and reinterventions within 30 days, were then considered in more detail. Initially, a range of pre-operative factors were compared to each of these outcomes in the CholeS cohort (Table 4). All considered outcomes were worse in patients with increasing age, ASA grade, male gender, non-elective admissions, the use of pre-operative CT/MRCP/ERCP, CBD dilation on pre-operative imaging, those without USS and for diagnoses of CBD stones or Cholecystitis. Increasing BMI was also associated with a significantly increased surgical duration as did thick-walled gallbladders and were more likely to be converted to open.

Multivariable analysis

A set of multivariable analyses were then performed, to assess whether there was an independent association between the Nassar scale and patient outcome, after accounting for other factors previously identified as being associated with patient outcome (Table 5). This found a range of factors that were independently associated with the patient outcomes being considered, including increasing patient age, non-elective admissions and increasing ASA grade. After accounting for these factors, the Nassar scale remained a significant predictor of all four outcomes (all p < 0.001), with odds ratios for Nassar grade 4–5 versus 1 of 13.5, 115.6, 3.18 and 2.91 for surgical duration of more than 90 min, conversion to open and 30-day complication and reintervention rates, respectively.

Discussion

We have shown that a simple scale of operative difficulty in laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be easily applied to patients across two separate large cohort databases. Despite the baseline differences in these datasets, the operative difficultly score remained highly clinical relevant. It would seem that, when given the concept and the criteria of the difficulty grading, a large number of surgeons will consistently classify cholecystectomies in a similar manner. We have also shown that a higher difficulty grade has strong clinical relevance, being associated with worse clinical outcomes, and that this association is independent of other factors on multivariable analysis.

Due to the variability of operative findings, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is one of the most unpredictable operations in general surgery, This can be due to anatomical reasons, but is mainly due to the effect of cholecystitis and fibrosis on the dissection planes in Calot’s triangle. Publications reporting surgical outcomes following cholecystectomy are difficult to compare, as currently no grading or scoring system is consistently used to document operative findings. This was why the CholeS study incorporated the Nassar intra-operative difficulty grading method [3] into its protocol [11] and asked participating surgeons to view online videos of varying Nassar grades prior to study commencement. Although a number of important clinical applications of the Nassar grading system have been reported, the scale has yet to be evaluated and validated in large cohorts of patients such as the present study. Previous publications using the scale addressed the optimisation of the management of complicated gallstone disease [19, 20] and the suitability of certain cases for single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy [21].

Very few intra-operative difficultly scores for use in cholecystectomy have been published [1, 3,4,5,6] (Table 6). Sugrue et al. have developed a scoring system using operative findings, incorporating the appearance of the gallbladder, presence of gallbladder distension, ease of access, potential biliary complications and time taken to identify cystic duct and artery [1]. However, no clinical outcome data were presented in this paper and no validation of its clinical usefulness was performed.

Cuschieri published a ‘scale of difficulty’ for laparoscopic cholecystectomy in a textbook in 1992 [22] and this was subsequently modified in a further publication in The Lancet in 1998 [2] (Table 6). However, it can be argued that with increasing skill level in laparoscopic surgery over the last 20 years, even very difficult operations can be now managed without conversion to open surgery. For example, laparoscopic “damage control” methods, including cholecystostomy, fundus first cholecystectomy and subtotal cholecystectomy, have been proposed to avoid conversion to open surgery [15, 23]. This means that the Cuschieri scale is no longer applicable in the current era. In addition, conversion to open surgery could be required in cases of fairly simple cholecystectomy due to other reasons, such as uncontrollable bleeding or iatrogenic injury. As previously reported by the CholeS study group, the threshold for conversion is likely to vary between surgeons, and may relate to several factors, such as patient related factors, surgeon’s experience and procedural difficulty [10].

A recent paper categorised intra-operative photographs of patients undergoing cholecystectomy and developed the ‘Parkland’ grading scale for cholecystectomy [24], which is broadly comparable to the Nassar operative difficulty scale. Outcome data were only presented for 50 patients, but increasing severity was associated with longer operating times, length of stay and post-operative bile leaks [24], which is in keeping with our findings.

Our future aim is to develop a risk prediction tool for intra-operative difficulty which will use pre-operative variables to predict a more difficult and taxing operation. This could then be used for the selection of patients for day-case surgery or to anticipate a difficult operation and either allow more theatre time or employ the services of a more specialist surgeon or unit.

This study has some limitations. There will be some subjectivity in the use of the operative difficultly scale between surgeons. There were some baseline clinical differences between the two datasets. The reference cohort was based on the experience of a specialist biliary surgeon that performed more 4000 laparoscopic cholecystectomies over more than 20 years, whilst the CholeS cohort was made up of over 8000 operations performed in a 2-month period by many surgeons with different types and degrees of experience. However, the fact that the Nassar operative difficulty scale remained clinically relevant in both datasets is a testament to its simplicity and clinical relevance. In contrast to other papers published on the operative difficulty of cholecystectomy [1, 22, 24], our paper used large, prospectively collected data with highly validated outcome data. Whilst the score was developed and used in a single-centre dataset with a long study duration, the validation has been performed in a dataset which includes multiple centres and high-quality external data validation.

Conclusion

We have shown that this simple operative difficulty scale can be used by multiple grades of surgeons (including trainees and consultants) and remain highly clinically relevant. Our study demonstrated the applicability, consistency and reproducibility of the grading process. It therefore provides a tool for reporting disease and intra-operative severity and can reliably be utilised in future research to adjust outcomes according to case mix and intra-operative difficulty. The grading of operative difficulty should be collected routinely.

Change history

10 February 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-023-09888-w

22 August 2018

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6377-8

References

Sugrue M, Sahebally SM, Ansaloni L, Zielinski MD (2015) Grading operative findings at laparoscopic cholecystectomy—a new scoring system. World J Emerg Surg 10:14

Hanna GB, Shimi SM, Cuschieri a (1998) Randomised study of influence of two-dimensional versus three-dimensional imaging on performance of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Lancet 351:248–251

Nassar AHM, Ashkar KA, Mohamed AY, Hafiz AA (1995) Is laparoscopic cholecystectomy possible without video technology? Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 4:63–65

Augustine A, Rao R, Vivek MAM (2014) A comprehensive predictive scoring method for difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Minim Access Surg 10:62

Randhawa JS, Pujahari AK (2009) Preoperative prediction of difficult lap chole: a scoring method. Indian J Surg 71:198–201

Gupta N, Ranjan G, Arora MP, Goswami B, Chaudhary P, Kapur A, Kumar R, Chand T (2013) Validation of a scoring system to predict difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Int J Surg 11:1002–1006

Sutton AJ, Vohra RS, Hollyman M, Marriott PJ, Buja A, Alderson D, Pasquali S, Griffiths EA (2017) Cost-effectiveness of emergency versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute gallbladder pathology. Br J Surg 104:98–107

CholeS Study Group, West Midlands Research Collaborative (2016) Population-based cohort study of outcomes following cholecystectomy for benign gallbladder diseases. Br J Surg 103:1704–1715

CholeS Study Group, West Midlands Research Collaborative (2016) Population-based cohort study of variation in the use of emergency cholecystectomy for benign gallbladder diseases. Br J Surg 103:1716–1726

Sutcliffe RP, Hollyman M, Hodson J, Bonney G, Vohra RS, Griffiths EA, CholeS Study Group WMRC (2016) Preoperative risk factors for conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy: a validated risk score derived from a prospective U.K. database of 8820 patients. HPB 18:922–928

Vohra RS, Spreadborough P, Johnstone M, Marriott P, Bhangu A, Alderson D, Morton DG, Griffiths EA (2015) Protocol for a multicentre, prospective, population-based cohort study of variation in practice of cholecystectomy and surgical outcomes (The CholeS study). BMJ Open 5:e006399

Nassar AHM, Mirza A, Qandeel H, Ahmed Z, Zino S (2016) Fluorocholangiography: reincarnation in the laparoscopic era—evaluation of intra-operative cholangiography in 3635 laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Surg Endosc 30:1804–1811

Hanif F, Ahmed Z, Samie MA, Nassar AHM (2010) Laparoscopic transcystic bile duct exploration: the treatment of first choice for common bile duct stones. Surg Endosc 24:1552–1556

Hamouda AH, Goh W, Mahmud S, Khan M, Nassar AHM (2007) Intraoperative cholangiography facilitates simple transcystic clearance of ductal stones in units without expertise for laparoscopic bile duct surgery. Surg Endosc 21:955–959

Mahmud S, Masaud M, Canna K, Nassar AHM (2002) Fundus-first laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a safe means of reducing the conversion rate. Surg Endosc 16:581–584

Mahmud S, Hamza Y, Nassar AHM (2001) The significance of cystic duct stones encountered during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 15:460–462

Way LW, Stewart L, Gantert W, Liu K, Lee CM, Whang K, Hunter JG (2003) Causes and prevention of laparoscopic bile duct injuries: analysis of 252 cases from a human factors and cognitive psychology perspective. Ann Surg 237:460–469

Koch M, Garden OJ, Padbury R, Rahbari NN, Adam R, Capussotti L, Fan ST, Yokoyama Y, Crawford M, Makuuchi M, Christophi C, Banting S, Brooke-Smith M, Usatoff V, Nagino M, Maddern G, Hugh TJ, Vauthey JN, Greig P, Rees M, Nimura Y, Figueras J, Dematteo RP, Büchler MW, Weitz J (2011) Bile leakage after hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery: a definition and grading of severity by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery. Surgery 149:680–688

Amboldi M, Amboldi A, Gherardi G, Bonandrini L (2011) Complications of videolaparoscopic cholecystectomy: a retrospective analysis of 1037 consecutive cases. Int Surg 96:35–44

Lirici MM, Califano A (2010) Management of complicated gallstones: results of an alternative approach to difficult cholecystectomies. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 19:304–315

Ye G, Qin Y, Xu S, Wu C, Wang S, Pan D, Wang X (2015) Comparison of transumbilical single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy and fourth-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Int J Clin Exp Med 8:7746–7753

Cuschieri A, Berci G (1992) Laparoscopic biliary surgery. Blackwell Scientific Publication, Edinburgh

Ashfaq A, Ahmadieh K, Shah AA, Chapital AB, Harold KL, Johnson DJ (2016) The difficult gall bladder: outcomes following laparoscopic cholecystectomy and the need for open conversion. Am J Surg 212:1261–1264

Madni T, Leshikar D, Minshall C, Nakonezny P, Cornelius C, Imran J, Clark A, Williams B, Eastman A, Minei J, Phelan H, Cripps M (2017) The Parkland grading scale for cholecystitis. Am J Surg 215:625–630

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the help of Amanda Kirkham, Statistician, Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit for help with managing the CholeS database.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Drs. Griffiths, Hodson, Vohra, Marriott, Katbeh, Zino and Nassar have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Additional information

Please find details of the CholeS management group, Collaborators and Data Validators in a supplementary file.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Griffiths, E.A., Hodson, J., Vohra, R.S. et al. Utilisation of an operative difficulty grading scale for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 33, 110–121 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6281-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6281-2